NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

Social Science Modeling and Information Visualization Workshop.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Popp, R. (NSI, Inc).

The Social Science Modeling and Information Visualization Workshop provided a unique forum for bringing together leading social scientists, researchers, modelers, and government stakeholders in one room to discuss the state-of-the-art and the future of quantitative/computational social science (Q/CSS) modeling and information visualization. Interdisciplinary quantitative and computational social science methods from mathematics, statistics, economics, political science, cultural anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, and modeling and simulation - coupled with advanced visualization techniques such as visual analytics - provide analysts and commanders with a needed means for understanding the cultures, motivations, intentions, opinions, perceptions, and people in troubled regions of the world.

Military commanders require means for detecting and anticipating long-term strategic instability. They have to get ahead and stay ahead of conflicts, whether those conflicts are within nation states, between nation states, and/or between non-nation states. In establishing or maintaining security in a region, cooperation and planning by the regional combatant commander is vital. It requires analysis of long-term strategic objectives in partnership with the regional nation states. Innovative tools provided by the quantitative and computational social sciences will enable military commanders to both prevent conflict and manage its aftermath when it does occur.

The need for interdisciplinary coordination among the academic, private, and public sectors, as well as interagency coordination among federal organizations, is critical to solving the strategic threat posed by dynamic and socially complex threats. Mitigating these threats requires applying quantitative and computational social sciences that offer a wide range of nonlinear mathematical and nondeterministic computational theories and models for investigating human social phenomena. Moreover, advanced visualization techniques are also critical to help elucidate – visually – complex socio-cultural situations and possible courses of action under consideration by decision-makers.

These social science modeling and visualization techniques apply at multiple levels of analysis, from cognition to strategic decision-making. They allow forecasts about conflict and cooperation to be understood at all levels of data aggregation from the individual to groups, tribes, societies, nation states, and the globe. These analytic techniques use the equations and algorithms of dynamical systems and visual analytics, and are based on models: models of reactions to external influences, models of reactions to deliberate actions, and stochastic models that inject uncertainties. Continued research in the areas of social science modeling and visualization are vital. However, the product of these research efforts can only be as good as the models, theories, and tools that underlie the effort.

The Department of Defense (DOD) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have responded to these needs and new developments in the field of quantitative/computational social science modeling and visualization by changing their orientation to social and cultural problems. While these efforts would not have been funded several years ago, they are cautiously being explored and supported today. The DOD and DHS have and continue to embrace this research area - through an iterative, spiral process where they will build a little, then learn a little - until there is a strong foundation for supporting the social sciences. The DOD and DHS have also broadened their horizons by looking outside the US Government (USG) to understand and mitigate threats by engaging corporations, non-profit organizations, centers of excellence, and academia. The DOD and DHS have recognized the need to respond to a new type of adversarial interaction. Current and future operations demand the capability to understand the social and cultural terrain and the various dimensions of human behavior within this terrain. This evolution will require a re-examination of DOD and DHS actions such as developing non-kinetic capabilities and increasing interagency coordination.

While the DOD and DHS are changing their orientation to quantitative/computational social science modeling, difficulties and challenges remain. First, opportunities and challenges in the theoretical domain include the need for better, scientifically grounded theories to explain socio-cultural phenomena related to national security. Better theories affect modeling on all levels. They yield clarified assumptions, better problem scoping and data collection, a common language to interpret analysis, and inform visualization options. Quantitative/computational social science presents the opportunity to integrate theories, explore their applicability, and test their validity.

A second challenge facing the social science modeling community is the need to clearly frame the core question. This is a step that is often overlooked in the creation of new social science models. The model’s intent must be clearly defined from the start. If the model is not framed correctly and if the assumptions, limitations, and anticipated outcomes of the model are not clear, the field of social science modeling can be easily tarnished. Part of the problem is the ambiguous and widespread use of the word “culture,” which can be used to mean many things. This term must be better defined and normalized to assist modelers in framing the problem.

The third challenge is the lack of strong datasets for social science researchers. Available datasets may either lack a strong methodology or be unavailable to the open source community. Additionally, because social, cultural, and behavioral issues have only recently come to the attention of policy- and decision-makers, data remains relatively sparse. New efforts and investment in strong datasets are required to fuel the progress of quantitative/computational social science.

Fourth, the USG must adapt to the open-source nature of many social, cultural, and behavioral issues of interest to the defense, homeland security, and intelligence community today. Not only do cleared facilities restrict the access of many researchers and subject matter experts, they also restrict the type of data that can be used and the distribution of the model’s output. Ultimately, open source will become the main source of socio-cultural information, and the USG must create environments for these developments to occur.

Finally, visualization should not be considered solely as the final step in the creation of a social science model; it must be considered from the very beginning. It is a form of analytic output that adds depth, value, and utility to an effort. Furthermore, visualization can be used for more than just analysis; it can also be used to evaluate data. Visualization is the means through which analysts and commanders receive and understand data. Its value should not be left as an afterthought.

The degree of interest and understanding in quantitative/computational social science exhibited by government stakeholders are higher than they have ever been before. New efforts at interagency coordination, particularly between the DOD and DHS are signs of the importance of this field. Likewise, the level of interest and enthusiasm shown by academia in participating in these efforts is unprecedented. The coalescing need for timely, accurate, socio-cultural modeling and visualization tools is growing to such an extent that calls for a concept of operations are emerging. However, further cooperation is needed across the USG to advance, guide, and shape the science and meet the growing need for socio-cultural understanding.

The Human Domain: The Unconventional Collection and Analysis Challenge Workshop.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Popp, R. (NSI, Inc).

One of the major challenges the US has faced during the opening decades of the 21st Century is the growth in the number and international reach of insurgents, terrorists, WMD proliferators and other sorts of nefarious groups. Among many others, the current situation in Iraq illustrates the difficulty of countering insurgencies once they have become violent and operationally well-established. The apparent transition of contemporary war away from the traditional physical battlefield towards the human element as the battlefield poses new challenges for both intelligence and operations – collections and analysis within the human domain requires new thinking and new methods.

The purpose of this workshop was to identify approaches to recognize and anticipate the conditions in which insurgents, terrorists, WMD proliferators and other sorts of nefarious groups tend to emerge, become operationally established, and choose to employ tactics counter to the interests of the US national security objectives. An underlying presumption of this workshop is that tackling these movements during their emergent phases is less costly in resources and lives, with more non-lethal options available for consideration, than after they have become fully established. Novel approaches to collections and analysis of the interactions within and between elements of the “human dimension” may lead us to greater potential for proactive rather than reactive capabilities, and certainly non-kinetic capabilities, not only within the military context, but within all components of national power.

Clearly, focusing on emergent violent groups and their activities will necessitate a shift in how the nation and its allies collects, analyzes, and acts upon information from and about these volatile environments. The workshop brought together a diverse group of physical and social scientists, academics, analysts, intelligence collection managers, operational planners, and decision makers to discuss novel techniques and methods for a more proactive approach to address the human dimension associated with insurgents, terrorists, WMD proliferators and other sorts of nefarious groups, and the impact of such an approach on training, planning, tasking, collection, analysis, and decision making in the coming decades.

EVOLUTION OF VIOLENT EXTREMISM

There is an important distinction between activism and radicalism. Activism is legal and nonviolent political action, while radicalism is illegal and violent political action. Activism is not necessarily a conveyor belt to radicalism. Individuals can be radicalized from any layer of society including neutral parties, sympathizers, and activists.

Government Sponsored Research on Violent Extremism

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is is laying the groundwork to conduct in-depth case studies of individuals engaged in terrorist violence in the US. At the group level, DHS is studying terrorist group rhetoric with a focus on both groups that have engaged in terrorism and groups that would be considered radical but that have not engaged in terrorism. The study will look at groups with similar ideologies and goals and try to understand why some groups choose violence and others do not. DHS will also work to identify characteristics of groups who participate in IED attacks. At the community level, DHS is involved in two primary activities. The first is evaluating whether survey data can shed light on radical activity in the US. Finally, DHS is working with START to study the effectiveness of counter radicalization programs conducted in five countries including Yemen, Indonesia, Columbia, Northern Ireland, and Saudi Arabia.

The Behavioral Analysis Unit is the newest organization within the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It is an operational unit that conducts research. Counterterrorism research within the unit is still in its infancy stages; however, some projects are currently underway dealing primarily with operational threat assessments. The most pertinent research efforts are in collaboration with DoD intelligence units. This work primarily focuses on radicalization by looking at the radicalization process in historic case studies. The FBI is also involved in another research effort in coordination with the WMD directorate, to look at 50 domestic cases in which offenders used WMD in the US.

The Defense Intelligence Socio-Cultural Dynamics Working Group (SCDWG) was created in 2002 to develop an enterprise solution to institutionalize Socio-Cultural Dynamics intelligence analysis. The group was asked to address the full scope of issues, from policy to tactical. The group was asked to define the role of intelligence in this area as well as to identify the “right tool for the right job.”

The Marine Corps Intelligence Activity (MCIA) is working on the next generation of cultural intelligence. They are working on visualizing cultural intelligence by “putting culture on the map.” Their second project is to support influence operations and irregular warfare by building partner capacities focused on the values and themes of sub-national groups. The third is cultural vignettes, which are short and focused products designed to create a specific cognitive map for each mission set. The fourth is building an analytic capacity by supporting uniquely trained cultural analysts, ensuring 24/7 reachback for deployed unites, and creating deployable analytic teams for contingency operations.

UNDERSTANDING SOCIO-CULTURAL DYNAMICS: TRADECRAFT AND OBSERVATIONS FROM A DISTANCE

Studies to understand a country and its people must be planned and carried out with nuance. Ethnic maps, a critical tool for US forces, have long been a political issue. It affects resource allocation, boundaries, and political formulae. In countries experiencing ethnic conflict, building a credible demographic baseline must be done before lasting geopolitical stability can be realized. Maps can help researchers and analysts understand the cultural geography of conflict. Chorological analysis, relating to the description or mapping of a region, can reveal causal linkages and patterns of political and social behavior that researchers were previously unaware of. Mapping the human terrain is needed to understand these complex problems.

Culture at a distance methodology from 1942 mostly comprised of several sources. Researchers studied travelers’ accounts, ethnographies, histories and other second hand sources including social science works. Content analysis finds its roots in these attempts. Post World War II, the DoD funded a great deal of social science research although only a small part of it was “culture at a distance”. They focused instead on models such as game theory. Their main interest was in political instability: its causes and indicators.

Today, the DoD has stated that socio-cultural data collection is everyone’s problem. However, the DoD does not currently have the knowledge and understanding of non-Western cultures and societies necessary to execute these missions. Because of this, there are several new culture at a distance methods. Computational modeling has become the sine qua non of culture at a distance method, but it suffers from considerable handicaps. Its emphasis on computational engineering leads to “everything looks like a nail” thinking. The problem with models is that many do not scale gracefully from explaining small scale issues to larger scale ones. Models are culturally and socially ignorant, which is frequently the case when engineers develop “new cultural theory” with little or no training in the fields of social science.

Socio-Cultural Tradecraft and Open Source Collection Requirements Management

Emerging violent non-state actors use or share a common story about their involvement to motivate and empower their groups, and attract and mobilize their audiences. The degree by which infringements are interpreted, personified, and perceived is the variable to which violence emerges. It is typically a conflict between the haves and the have not’s over a particular issue. Modeling these relationships requires a four prong approach: anthropological research; open source collection; human intelligence collection; and environmental research. The model will synthesize that information to assess behavior.

Cultural geography is the study of spatial variations among cultural groups and the spatial functioning of society. Urban geography is the study of how cities function, their internal systems and structure, and the external influences on them and the study of the variation among cities and their internal and external relationships. The human geography areas of interest include economics, demographics, politics, culture, combined social implications, and technology/infrastructure. Cultural geographers face several challenges. First, experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq have shown that neighborhood level data is necessary for operational and tactical planning (Intelligence Preparation of Battlefield). Second, there is a lack of reliable data sets. For example, there has been no census in Lebanon since 1932. Third, closed countries, such as North Korea, pose a problem. Fourth, no city level data exists or it is difficult to obtain in grey literature. Fifth, there is a lack of current academic studies. Therefore, researchers must take a multidiscipline approach and use sources from a variety of fields to complete their research.

Remote Observing Using Large Data Sets

The nexus for computer forensics is addressing large data sets. Researchers and developers are working with open source information and applying analytic tools to it. They have discovered that it is considered novel in the US to use the same tool to address open source and classified datasets and merge them. One large data set, INSPIRE, was developed to allow an analyst to look at a large number of text documents and look for words and phrases. The program graphically portrays the output. A subsequent project is porting INSPIRE over to high power computing environment.</p>, <p>Content analyzers are another tool for working with very large datasets. The tool makes coding schemes in the process of creating large data sets from large text sources. It has an automatic generation process that is transparent. From this data, the analyst produces dashboard like metrics to describe the data. This has created an impetus to create measures of effectiveness and validation. The team discovered that people and computer coders make different types of errors. Humans make boredom errors. Their accuracy always goes down over time. However, if a computer sees a new word, it will not code it. The operation code measures how you present self and others in text on cooperative or conflictive dimensions. The tool can also extract and compare entities for distrustfulness. They use a combination of tools to look for themes and people. It is a pragmatic way to build structure while reducing the analysts’ reading load.

UNDERSTANDING THE HUMAN TERRAIN: TRADECRAFT AND STREETCRAFT METHODS

Applying Law Enforcement Methods to Gathering Human Terrain

An appropriate balance of skills, knowledge, and abilities need to be incorporated into an analysis team. It needs to be half Army Ranger company and half artist colony. Good analysts are adaptable, intellectually flexible, and have a high degree of comfort with ambiguity. An analyst’s job is simple: they read, write, and present. In the development of a good analyst, no preparation matches analyst’s comfort level with ambiguity. Furthermore, the depth and breadth of an analyst’s rolodex is more important than personal understanding of a region or topic. Analysts must also exhibit finesse - the practice of combining knowledge, thought, and intellectual stamina. Personal conviction of paying attention to a few small details that have enormous impact on outcomes or intelligence is critical. Good analysts are those who care as much about operational environment as producing a final product.

Approximately 90 percent of the food we eat, clothes we wear, and products we use are imported daily via commercial maritime transport. Threats to ships and ports include drug smuggling, stowaways, and terrorists. Drugs are often creatively hidden in cargo, such as cocaine stashed inside individual bananas. Drug couriers can also be hidden away in cargo shipments. These could easily be terrorists or terrorist materials. According to a US Coast Guard report, 25 Islamic extremists entered the US onboard commercial cargo vessels. Narco traffickers are more frequently taking consignments of extremists to the US. There is an increasing level of cooperation between MS-13, narco traffickers, and Islamists. The human collection component is critical to stopping these illegal activities because Customs cannot provide the level of analysis needed.

The Department of Commerce’s task is to prevent the export of US dual-use goods and technology that may be used by rogue states or terrorists to make chemical, biological or nuclear weapons. The Office of Export Enforcement’s priorities are WMD proliferation, terrorism/terrorist support, and unauthorized military/government use. Commerce is unique in that it has civil penalties, in addition to criminal penalties, in which one only needs the preponderance of the evidence to convict. The challenge of identifying and stopping illegal dual use exports is making sure at every step of the process that all of the people involved can validate the end use. It gets murky because end users lie and some components are working with the end users. Globalization is also a national security challenge and many transactions are moving over the internet. The US government does not move at the speed of business.

The Criminal Investigation Task Force (CITF) was created in early 2002 by the DoD to conduct investigations of detainees captured in the Global War on Terrorism. CIFT became the investigative arm of the DoD after OSD was given the mission to prosecute the detainees. OSD transferred the responsibility to the Army, where the CITF now falls under Army Criminal Investigation Command (CID). The need for analysts and intelligence professionals was huge, especially for law enforcement officials not used to working with classified materials. Likewise, law enforcement people need to communicate with the combatant commanders. Terrorists groups often act like organized crime groups. The intelligence community may not have much experience in this, but law enforcement does. It also has experience in conducting interrogations. To conduct interviews effectively the interrogator must put all biases aside and just accept the culture for what it is. The interrogator must get down to the bedrock of cultural foundation.

Applying Social Science Methods to Understanding the Human Terrain

Social science is the application of consistent, rigorous methods of research and analysis to describe or explain social life. Its purpose is inference: using facts we do know (data, observations) to learn about facts we do not know (theories, hypotheses). It is used to make descriptive inferences (semantic program); to place or make observations within a conceptual framework to allow people to understand a phenomenon; and to make causal inferences (syntactic / pragmatic program). Because of the large number of potential causal factors for any social phenomenon, establishing causation is difficult. If we can establish the cause of a social phenomenon, then we can make policy to affect that phenomenon.

Data collection involves various methodologies such as ethnography: participant observation; surveys: interview processes (formal, informal, group, individual, structured, unstructured); record or document review; and history: conducting interviews or reviewing documents about the past. Data analysis involves direct interpretation: analysis by an individual’s reflection and synthesis; quantitative analysis: using standard methods of statistics to ascertain relationships; and formal modeling: analysis by creating a formal system that mimics the world. In evaluating which method is most appropriate, it is important to keep in mind that multidisciplinary methods reinforce one another.

Field research in Iraq is particularly complicated. Researchers must use semantic programs and descriptive inference as well as create a pragmatic program with causal inference. Some of the challenges include sampling, reactive bias, and interpretive bias. Coping with these problems is done by working through local researchers, geographic sampling and purposive sampling, redundancy of methods, and redundancy of research networks. On the ground analysis is informed by area studies, topic specialization, and occasional forays into population.

There is a great need to improve intelligence support to stability operations. To do this, analysts must embrace the importance of understanding the human terrain. There are three key elements to the human terrain. The first is developing a socio-cultural dynamics data network and repository. The second is developing data gathering, visualization, and analytic tools. The third is recruiting, training, and deploying experts to support decision-making.

To understand counterinsurgency, you must first understand and define the elements involved. Collecting information for COIN operations involves identifying key groups in a society and representing where they are located on a map. For each group, researchers seek to identify security (level, sources, threats); income and services (level, sources, gaps); beliefs and communications systems (narratives, symbols, norms and sanctions); and authority structures & figures (identity, structures, levels of authority).

Soldiers as Human Terrain Sensors

The Civil Affairs (CA) information objectives were to provide multi-dimensional situational understanding, provide situational analysis, and to work on the development of possible solution sets. The foci of CA operations are human terrain identification and prioritization (sphere of influence management) and civil reconnaissance. Within the human terrain network, there are sphere of influence engagements. These works identified political/tribal leaders throughout the district and their areas of influence to facilitate reconciliation efforts. They also identified facility managers/public works workers to facilitate transition to Iraqis fixing Iraqi problems. They also prioritized efforts to optimize limited resources for engagement.

There are three critical nodes in the CA analysis process. The first is collection. The information is the critical base element to the process. Without this, there is no system. The second is consolidation. Analysis and understanding the information makes the process function. It is an art and a science. The third is dissemination. Sharing the situational understanding is the key to success. Dissemination must flow up and down in order to coordinate and integrate with partners.

Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) have become a key tool for the international community to assist Afghanistan in becoming a secure and self-sustaining Republic. They represent, at the local level, the combined will of the international community to help the government and the civil society of Afghanistan become more stable and prosperous. PRTs, due to their provincial focus and civil-military resources, have wide latitude to accomplish their mission of extending the authority of the Government by improving security, supporting good governance and enabling economic development. This engagement of diplomatic, military and economic power by Nations at the provincial level allied with the wide latitude to accomplish their mission has been a strength, as it provides flexibility of approach and resources to support the provincial government structures and improve security.</p>, <p>The Humanitarian Information Unit (HIU) serves as a United States Government (USG) interagency center to identify, collect, analyze and disseminate unclassified information critical to USG decision makers and partners in preparation for and response to humanitarian emergencies worldwide, and to promote best practices for humanitarian information management.

Civilians as Human Terrain Sensors

In order to operate effectively in Afghanistan, warfighters need to understand the cultural context and history of the nation. An anthropology background by itself is not always useful. Human Terrain Teams (HTTs) and others need culture specific knowledge to achieve their mission in foreign countries. An open source portal exists to provide a civilian based source of socio-cultural information on Afghanistan. The portal facilitates a subject matter expert network to encourage interaction among the key players including the Department of State (DoS), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the US Agency for International Development (USAID), Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs), and soldiers. The site drills down to the provincial level where 21 of 34 provinces have been completed. The site provides information on detailed maps, refugees, education, health, topographic information, etc.

SUPPORTING ANALYTIC DISCIPLINES

Modeling and Visualization Workshop Summary

The objective of the Social Science Modeling and Visualization Workshop, held in January 2008, was to provide a “mixing bowl” for social scientists, modelers, researchers and government stakeholders to discuss the state-of-the-art in methods/models/visualization and their potential application in SMA efforts. Models can clarify complex situations, test assumptions, aid decision making, explore co-evolutionary motivations and bound the expected and outlier behaviors. Modeling can capture dynamical, non-linear processes. They can be multi-level, multi-scale behavior representations. Other benefits include that models can assist in training decision makers on the consequences of their policies/decisions. Visualization is a critical component of modeling. Therefore, it needs to be considered from the beginning of a project. Visualization serves a variety of functions include support of knowledge management, contextual visualization, relational visualization, identification of key features/nodes/information, understanding of decisions/complex processes, and evaluation/inspection of the data. Models must be verified, valid, and credible. The theoretic framework of social science modeling and visualization still needs work. Opportunities and challenges include the need for better, scientifically grounded theories. The federal government is interested in social science, but struggling to determine how to support it. It will take 4-5 years to reach robust funding levels.

Evolutionary Agent-based Modeling and Game Theoretic Simulations

Agent Based Modeling (ABM) is successful in the social science arena because as in the traditional approach to formal modeling, the goal is reducing the social landscape to a set of meaningful variables and specific mathematical equations. ABM brings to social science the ability to begin with a social landscape of entities in the world. It can identify basic relationships between actors. All models are developed or designed to answer a class of questions. ABMs are typically designed to answer questions that are intractable through earlier and more traditional mathematical or statistical methods, such as complex emergent patterns in large systems of agents. The beauty of ABM is that it can conduct experiments about shifting policies. All this can be done in silicon because you cannot manipulate players in the real world. ABM is a specific kind of simulation. It provides an experimental setting for finding patterns that are not very obvious.

Game theory is a branch of applied mathematics that formally models strategic behavior. Game theory is an approach to aid in articulating and understanding important factors of conflicts / disputes / coalitions. Game theory is neither prescriptive nor descriptive; nor is it normative. It is a theoretical tool. Game theory does not provide an answer; it provides a helpful way to frame the question to better understand the situation. If the assumptions are correct, game theory will provide an answer. Some assumptions of the theory include (bounded) rationality, complete information, and preference hierarchy for players (utility). In conclusion, it is important to remember that people are not agents. Game theory requires assumptions about behavior. It provides insight and understanding, but people are more complex than mathematical models. Finally, as in any model, if you put garbage in, you get garbage out.

Data Fusion / Integration and Detecting Patterns in Heterogeneous Data Sets

The defense and intelligence communities are making great progress in the social sciences. Many agencies now realize the importance of social science approaches, in combination with more traditional approaches. Often, people want to know why if we can go to the moon we cannot accurately model social science. It is because people are complex intelligent agents with feedback. They have multiple incentives, multiple allegiances, and multiple groups. Humans also exhibit adversarial behavior. They provide inaccurate and misleading information. Behavior is not invariant. There is a hierarchy of challenges in data fusion. The first is registration and entity resolution. The second is group and network detection. The third is feature construction and recognition. The fourth is complex event detection. The fifth is that concepts in models are inherently fuzzy. There is a prediction versus risk relation. And risk brings additional scrutiny and preparation challenges.

Data fusion technologies encompass a variety of characteristics. It is historically a deductively-based inferencing / estimation process. The resulting observations and estimates produce random variables optimized for minimum uncertainty. The process is adaptive in various ways. It enables observation management, process adaptation, and beneficial actions. Data fusion models can be used to analyze a broad set of areas. The physical domain is the easiest to accomplish fusion. This includes weapon systems and weather reports. The information domain is harder. This includes symbolic representation and interpretations of data and models. The cognitive domain includes beliefs, values, and emotions and is the most difficult to fuse.

Efforts are underway to create an automated multi-source, multi-sensor, multi-data fusion tool. One way they are doing this is by looking at textual information. They take documents of different types, use ABA tools and extract antecedents. The tools can grab information, bring it together, and end up with predictive models. Working toward multi-focused analysis, the tool must overcome the problem of sorting through tons of information.

Large Data Sets and Knowledge Extraction Techniques

Large data and visualization efforts are becoming an ever growing avalanche within the social science community. Loading all the data is hopeless. Therefore, efforts have focused on trying to load the structure of the data. This results in maximum expressiveness with minimum size. The structure of the data for documents includes terms, entities, and concepts. The structure for transaction, travel, and communication records include people, places, organizations, and relationships. However, smart loading still requires human guidance. A sandbox is an environment for “what if” questions and for constructing arguments. It should have quick access to exploratory tools and answer the question, “How are these actors connected?” The system’s job is to track workflow and allow for annotations and assumptions. The analyst can backtrack and replay, branch, and recombine. He may also retract or change assumptions. The output should embody a complete chain of reasoning.

Work is being undertaken to determine whether researchers could construct a scaffold for the data that can say something about the dataset. The geometry in the data set might help pull out information. By comparison if you look at physics, the math needed to model it is very tame math. In biology, the math needed is fundamentally different. Even though researchers have not discovered the laws of social science, there are some regularities, although they have not been captured in math to a sufficient depth.

The scale and speed of the data means that the classic, craftsman approach to machine learning is no longer possible. The answer is a commodity, hands-on model. This is a challenging task. Not only does commodity mean that researchers have to develop algorithms that are robust in the face of noise, skew, and the host of other ills; it also means that they have to work out how to set all algorithm parameters from the data or the context, so that the human analyst need not concern themselves with them. There is no single algorithmic magic bullet. There are lots of pattern recognition algorithms; some are well known, including decision trees, support vector machines, neural nets, nearest neighbors, naive Bayes. Ensembles are the first and the most powerful of the techniques to know about, as they permit you to squeeze all possible accuracy out of your data.

The role of moral emotions in predicting political attitudes about post-war Iraq

Author: Polansky (Pagano), S. & Huo, Y. J.

Abstract

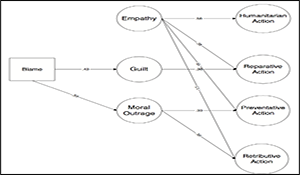

A web-based study of 393 undergraduates at a public university in the United States was conducted to examine the relationship between moral emotions (i.e., emotions that motivate prosocial tendencies) and support for political actions to assist Iraqi citizens after the Second Gulf War (2003–2004). Previous work on emotions and prosocial tendencies has focused on empathy. In the context of post-war Iraq, we found that while empathy predicted support for a number of different political actions that have the potential to advance the welfare of the Iraqi people (humanitarian action in particular), guilt over the U.S. invasion was an important predictor of support for reparative actions (i.e., restoring damage created by the U.S. military), and moral outrage toward Saddam Hussein and his regime was the best predictor of support for political actions to prevent future harm to the Iraqi people and to punish the perpetrators. Our findings demonstrate the utility of an emotion-specific framework for understanding why and what type of political actions individuals will support. And in contrast to the traditional view that emotions are an impediment to rationality, our findings suggest that they can serve as a potentially powerful vehicle for motivating political engagement among the citizenry.

Conclusion

Each study inevitably has its limitations. However, we believe that the strength of the current study lies in its systematic examination of the specific pattern of relationships between each of three moral emotions and support for different political actions in the context of an engaging and important real-life political event. This examination allows us to infer which discrete emotion is most strongly associated with a given form of political support. The differences in the relation- ships between each of these emotions and their related action tendencies have implications for the type of political appeals that should be made. These political appeals may in turn have consequences for helping behavior and political support. The overall pattern of results from this study therefore provides support for the use of empathy, guilt, and moral outrage in concert with one another in a focused and relatively comprehensive approach to motivate support for distinct political actions.

Citation

Pagano, S. J. & Huo, Y. J. (2007). “The role of moral emotions in predicting political attitudes about post-war Iraq.” Political Psychology, 28(2), 227-255.

Emergent Information Technologies and Enabling Policies for Counter-Terrorism.

Editors: Popp, R. & Yen, J.

This book explores both counter-terrorism and enabling policy dimensions of emerging information technologies in national security. After the September 11th attacks, “connecting the dots” has become the watchword for using information and intelligence to protect the United States from future terrorist attacks. Advanced and emerging information technologies offer key assets in confronting a secretive, asymmetric, and networked enemy. Yet, in a free and open society, policies must ensure that these powerful technologies are used responsibly, and that privacy and civil liberties remain protected. Emergent Information Technologies and Enabling Policies for Counter-Terorrism provides a unique, integrated treatment of cutting-edge counter-terrorism technologies and their corresponding policy options. Featuring contributions from nationally recognized authorities and experts, this book brings together a diverse knowledge base for those charged with protecting our nation from terrorist attacks while preserving our civil liberties.

Topics covered include:

- Counter-terrorism modeling

- Quantitative and computational social science

- Signal processing and information management techniques

- Semantic Web and knowledge management technologies

- Information and intelligence sharing technologies

- Text/data processing and language translation technologies

- Social network analysis

- Legal standards for data mining

- Potential structures for enabling policies

- Technical system design to support policy

Countering terrorism in today’s world requires innovative technologies and corresponding creative policies; the two cannot be practically and realistically addressed separately. Emergent Information Technologies and Enabling Policies for Counter-Terrorism offers a comprehensive examination of both areas, serving as an essential resource for students, practitioners, researchers, developers, and decision-makers.

Citation

Popp, R. and J. Yen, Emergent Information Technologies and Enabling Policies for Counter-Terrorism, Wiley-IEEE Press, Jun. 2006.

Countering Terrorism through Information and Privacy Protection Technologies

Author: Popp, R. & Poindexter, J.

Abstract

Security and privacy aren’t dichotomous or conflicting concerns—the solution lies in developing and integrating advanced information technologies for counterterrorism along with privacy-protection technologies to safeguard civil liberties. Coordinated policies can help bind the two to their intended use.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 transformed America like no other event since Pearl Harbor. The resulting battle against ter- rorism has become a national focus, and “con- necting the dots” has become the watchword for using information and intelligence to protect the US from future attacks. Advanced and emerging information technologies offer key assets in confronting a secretive, asymmetric, and networked enemy. Yet, in a free and open society, policies must ensure that these powerful technologies are used responsibly and that privacy and civil liberties re- main protected. In short, Americans want the govern- ment to protect them from terrorist attacks, but fear the privacy implications of the government’s use of powerful technology inadequately controlled by regulation and oversight. Some people believe the dual objectives of greater security and greater privacy present competing needs and require a trade-off; others disagree. This article describes a vision for countering terror- ism through information and privacy-protection tech- nologies. This vision was initially imagined as part of a research and development (R&D) agenda sponsored by DARPA in 2002 in the form of the Information Aware- ness Office (IAO) and the Total Information Awareness (TIA) program. It includes a critical focus and commit- ment to delicately balancing national security objectives with privacy and civil liberties. We strongly believe that the two don’t conflict and that the ultimate solution lies in utilizing information technologies for counterterror- ism along with privacy-protection technologies to safe- guard civil liberties, and twining them together with coordinated policies that bind them to their intended use.

Conclusion

Information and privacy-protection technologies are powerful tools for counterterrorism, but it’s a mistake to view technology as the complete solution to the prob- lem. Rather, the solution is a product of the whole system—the people, culture, policy, process, and tech- nology. Technological tools can help analysts do their jobs better, automate some functions that analysts would otherwise have to perform manually, and even do some early sorting of masses of data. But in the complex world of counterterrorism, the technologies alone aren’t likely to be the only source for a conclusion or decision. Ultimately, the goal should be to understand the level of improvement possible in our counterterrorism opera- tions using advanced tools such as those described here but also to consider their impact—if any—on privacy. If research shows that a significant improvement to detect and preempt terrorism is possible while still protecting the privacy of nonterrorists, then it’s up to the govern- ment and the public to decide whether to change exist- ing laws and policies. However, research is critical to prove the value (and limits) of this work, so it’s unrealistic to draw conclusions about its outcomes prior to R&D completion. As has been reported,6 research and devel- opment continues on information technologies to im- prove national security; encouragingly, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) is embarking on an R&D program to address many of the concerns raised about potential privacy infringements.

Citation

Popp, R. and J. Poindexter, “Countering Terrorism through Information and Privacy Protection Technologies,” IEEE Security and Privacy, IEEE Computer Society, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 18-27, Nov/Dec, 2006.

Countering Terrorism Through Information Technology

Author: Popp, R. et al.

September 11, 2001 might have been just another day if the U.S. intelligence agencies had been better equipped with information technology, according to the report of Congress’s Joint Inquiry into the events leading up to the Sept. 11 attacks. The report claims that enough relevant data was resident in existing U.S. foreign intelligence databases that had the “dots” been connected—that is, had intelligence analysts had IT at their disposal to access and analyze all of the available pertinent information—the worst foreign terrorist attack to ever occur on U.S. soil could have been exposed and stopped.

In the aftermath of the Sept. 11th terrorist attack, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)—the U.S. Defense Department agency that engages in high-risk/high-payoff research for the defense department and national security community—focused and accelerated its counterterrorism thrust. The over- arching goal was to empower users within the foreign intelligence and counterterrorism communities with IT so they could anticipate and ultimately preempt terrorist attacks by allowing them to find and share information faster, collaborate across multiple agencies in a more agile manner, connect the dots better, conduct quicker and bet- ter analyses, and enable better decision making.

The world has changed dramatically since the Cold War era, when there were only two superpowers. During those years, the enemy was clear, the U.S. was well postured around a relatively long-term stable threat, and it was fairly straightforward to identify the intelligence collection targets. Today, we are faced with a new world in which change occurs very rapidly, and the enemy is asymmetric and poses a very different challenge; the most signif- icant threat today is foreign terrorists and terrorist networks whose identities and whereabouts we do not always know.

What is the nature of the terrorist threat? Historically, terrorism has been a weapon of the weak characterized by the systematic use of actual or threatened physical violence, in pursuit of political objectives, against innocent civilians. Terrorist motives are to create a general climate of fear to coerce governments and the broader citizenry into ceding to the terrorist group’s political objectives. Terrorism today is transnational in scope, reach, and presence, and this is perhaps its greatest source of power. Terrorist acts are planned and perpetrated by collections of loosely organized people operating in shadowy networks that are difficult to define and identify. They move freely throughout the world, hide when nec- essary, and exploit safe harbors proffered by rogue entities. They find unpunished and oftentimes unidentifiable sponsorship and support, operate in small independent cells, strike infrequently, and utilize weapons of mass effect and the media’s response in an attempt to influence governments.

There are numerous challenges to counterterrorism today. As we noted earlier, identifying terrorists and terrorist cells whose identities and whereabouts we do not always know is difficult. Equally difficult is detecting and preempting terrorists engaged in adverse actions and plots against the U.S. Terrorism is considered a low-intensity/low-density form of warfare; however, terrorist plots and activities will leave an information signature, albeit not one that is easily detected. In all cases, and as certainly has been widely reported about the Sept. 11 plot, terrorists have left detectable clues—the significance of which, however, is generally not understood until after an attack. The goal is to empower analysts with tools to detect and understand these clues long before an attack is scheduled to occur, so appropriate measures can be taken by decision- and policymakers to preempt such attacks.

Citation

Popp, R., T. Armour, T. Senator and K. Numrych, “Countering Terrorism through Information Technology,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 36–43, Mar 2004.

m-Best S-D Assignment Algorithm with Application to Multitarget Tracking.

Author: Popp, R., Pattipati, K. & Bar-Shalom, Y.

Abstract

In this paper we describe a novel data association algorithm, termed m-best S-D, that determines in O(mSkn^3) time (m assignments, S >=3 lists of size n, k relaxations) the (approximately) m-best solutions to an S-D assignment problem. The m-best S-D algorithm is applicable to tracking problems where either the sensors are synchronized or the sensors and/or the targets are very slow moving. The significance of this work is that the m-best S-D assignment algorithm (in a sliding window mode) can provide for an efficient implementation of a suboptimal multiple hypothesis tracking (MHT) algorithm by obviating the need for a brute force enumeration of an exponential number of joint hypotheses. We first describe the general problem for which the m-best S-D applies. Specifically, given line of sight (LOS) (i.e., incomplete position) measurements from S sensors, sets of complete position measurements are extracted, namely, the 1st,2nd,…,mth best (in terms of likelihood) sets of composite measurements are determined by solving a static S-D assignment problem. Utilizing the joint likelihood functions used to determine the m-best S-D assignment solutions, the composite measurements are then quantified with a probability of being correct using a JPDA-like (joint probabilistic data association) technique. Lists of composite measurements from successive scans, along with their corresponding probabilities, are used in turn with a state estimator in a dynamic 2-D assignment algorithm to estimate the states of moving targets over time. The dynamic assignment cost coefficients are based on a likelihood function that incorporates the “true” composite measurement probabilities obtained from the (static) m-best S-D assignment solutions. We demonstrate the merits of the m-best S-D algorithm by applying it to a simulated multitarget passive sensor track formation and maintenance problem, consisting of multiple time samples of LOS measurements originating from multiple (S = 7) synchronized high frequency direction finding sensors.

Conclusion

In this paper we described an efficient and novel approach to data association based on the m-best S-D assignment algorithm. We demonstrated the feasibility of the m-best S-D assignment algorithm for track formation and maintenance using a passive sensor multitarget tracking problem (operating in a type III configuration [5]). We showed how to efficiently (and nonenumeratively) extract sets of complete position “composite measurements” and determine their probabilities using a JPDA-like technique (based on the likelihoods associated with the feasible joint events corresponding to the (static) m-best S-D assignment solutions). We then used the series of composite measurement lists, along with their corresponding probabilities, in a dynamic 2-D assignment algorithm to estimate the states of the moving targets over time. We formulated the 2-D assignment cost coefficients using a likelihood function that incorporates the “true” composite measurement probabilities. Using a simulated passive sensor multitarget tracking problem, we showed that the m-best S-D assignment algorithm can perform well. Another significance of this work is that the m-best S-D assignment algorithm (in a sliding window mode) provides for an efficient implementation of a suboptimal MHT algorithm by obviating the need for a brute force enumeration of an exponential number of joint hypotheses.

Citation

Popp, R., K. Pattipati and Y. Bar-Shalom, “m-best SD Assignment Algorithm with Application to Multitarget Tracking,” IEEE Trans. Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 22-39, Jan 2001.

Distributed- and Shared-Memory Parallelizations of Assignment-Based Data Association for Multitarget Tracking.

Author: Popp, R., Pattipati, K. & Bar-Shalom, Y.

Abstract

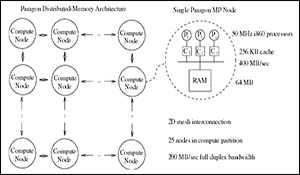

To date, there has been a lack of efficient and practical distributed- and shared-memory parallelizations of the data association problem for multitarget tracking. Filling this gap is one of the primary focuses of the present work. We begin by describing our data association algo- rithm in terms of an Interacting Multiple Model (IMM) state estimator embedded into an optimization framework, namely, a two-dimensional (2D) assignment problem (i.e., weighted bipartite matching). Contrary to conventional wisdom, we show that the data association (or optimization) problem is not the major computational bottleneck; instead, the interface to the optimization problem, namely, computing the rather numerous gating tests and IMM state estimates, covariance calculations, and likelihood function evaluations (used as cost coefficients in the 2D assignment problem), is the primary source of the workload. Hence, for both a general-purpose shared-memory MIMD (Multiple Instruction Multiple Data) multiprocessor system and a distributed-memory Intel Paragon high-performance computer, we developed parallelizations of the data association problem that focus on the interface problem. For the former, a coarse-grained dynamic parallelization was developed that realizes excellent per- formance (i.e., superlinear speedups) independent of numerous factors influencing problem size (e.g., many models in the IMM, dense?cluttered environments, contentious target-measure- ment data, etc.). For the latter, an SPMD (Single Program Multiple Data) parallelization was developed that realizes near-linear speedups using relatively simple dynamic task allocation algorithms. Using a real measurement database based on two FAA air traffic control radars, we show that the parallelizations developed in this work offer great promise in practice.

Conclusion

In this work, in the context of a sparse multitarget air traffic surveillance problem, we showed (via workload analysis) that the interface to the data association (optimi- zation) problem was the computational bottleneck, as opposed to the optimization problem itself. We then described a coarse-grained shared-memory parallelization of the data association interface problem that yielded excellent performance results, i.e., superlinear speedups, scalable, performance independent of numerous factors influ- encing problem size, e.g., many models in the IMM, large track?scan set sizes, or contentious target-measurement multitarget data due to clutter, dense scenarios, and?or coarse gating policies. In the case of a fine-grained parallelization, the performance was dependent on the number of filter models used, yielding negligible throughput for any number of filter models, marginal speedups when many models were used, and worse execution time than sequential time when three or less filter models were used. We then described an SPMD distributed-memory parallelization of the data association interface problem that also yielded excellent performance (i.e., near-linear speedups) configured with relatively simple task allocation algorithms. Furthermore, consistent with other research efforts, in the context of multitarget tracking, we showed that using relatively simple dynamic (heuristic) task allocation algorithms can offer great promise in practice.

Citation

Popp, R., K. Pattipati and Y. Bar-Shalom, “Distributed- and Shared-Memory Parallelizations of Assignment-Based Data Association for Multi-target Tracking,” Annals of Operations Research: Special Issue on Parallel Optimization, vol. 90, pp. 293–322, Sept 1999.

Dynamically Adaptable m-Best 2-D Assignment Algorithm and Multilevel Parallelization

Author: Popp, R., Pattipati, K. & Bar-Shalom, Y.

Abstract

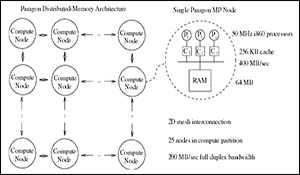

In recent years, there has been considerable interest within the tracking community in an approach to data association based on the m-best two-dimensional (2-D) assignment algorithm. Much of the interest has been spurred by its ability to provide various efficient data association solutions, including joint probabilistic data association (JPDA) and multiple hypothesis tracking (MHT). The focus of this work is to describe several recent improvements to the m-best 2-D assignment algorithm. One improvement is to utilize a nonintrusive 2-D assignment algorithm switching mechanism, based on a problem sparsity threshold. Dynamic switching between two different 2-D assignment algorithms, highly suited for sparse and dense problems, respectively, enables more efficient solutions to the numerous 2-D assignment problems generated in the m-best 2-D assignment framework. Another improvement is to utilize a multilevel parallelization enabling many independent and highly parallelizable tasks to be executed concurrently, including 1) solving the multiple 2-D assignment problems via a parallelization of the m-best partitioning task, and 2) calculating the numerous gating tests, state estimates, covariance calculations, and likelihood function evaluations (used as cost coefficients in the 2-D assignment problem) via a parallelization of the data association interface task. Using both simulated data and an air traffic surveillance (ATS) problem based on data from two Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) air traffic control radars, we demonstrate that efficient solutions to the data association problem are obtainable using our improvements in the m-best 2-D assignment algorithm.

Conclusion

Spurred on by recent interest in the m-best 2-D assignment algorithm for the data association problem, in this paper we described several improvements that enable much more efficient solutions to the data association problem, especially in dynamic environments. One improvement was to utilize a nonintrusive 2-D assignment algorithm switching mechanism, based on a problem sparsity threshold, enabling the auction and JVC 2-D assignment algorithms, each highly suited for sparse and dense problems, respectively, to efficiently solve the numerous 2-D assignment problems generated as part of the partitioning task. Another improvement was to utilize a multilevel parallelization of the data association problem, i.e., we parallelized the partitioning task and the data association interface task. This parallelization enables not only multiple 2-D assignment problems to be executed in parallel, but also the numerous gating tests, state estimates, covariance calculations, and likelihood function evaluations (used as cost coefficients in the 2-D assignment problem). Finally, using both simulated data and an ATS problem based on two FAA air traffic control radars, we demonstrated that more efficient solutions to the data association problem are possible when using the m-best 2-D assignment algorithm with our improvements incorporated.

Citation

Popp, R., K. Pattipati and Y. Bar-Shalom, “Dynamically Adaptable m-Best 2D Assignment Algorithm and Multi-Level Parallelization,” IEEE Trans. Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 1145–1160, Oct 1999.

Shared Memory Parallelization of the Data Association Problem in Multi-Target Tracking

Author: Popp, R., Pattipati, K., Bar-Shalom, Y. & Ammar, R.

Abstract

The focus of this paper is to present the results of our investigation and evaluation of various shared-memory parallelizations of the data association problem in multitarget tracking. The multitarget tracking algorithm developed was for a sparse air traffic surveillance problem, and is based on an Interacting Multiple Model (IMM) state estimator embedded into the (2D) assignment framework. The IMM estimator imposes a computational burden in terms of both space and time complexity, since more than one filter model is used to calculate state estimates, covariances, and likelihood functions. In fact, contrary to conventional wisdom, for sparse multitarget tracking problems, we show that the assignment (or data association) problem is not the major computational bottleneck. Instead, the interface to the assignment problem, namely, computing the rather numerous gating tests and IMM state estimates, covariance calculations, and likelihood function evaluations (used as cost coefficients in the assignment problem), is the major source of the workload. Using a measurement database based on two FAA air traffic control radars, we show that a “coarse-grained” (dynamic) parallelization across the numerous tracks found in a multitarget tracking problem is robust, scalable, and demonstrates superior computational performance to previously proposed “fine-grained” (static) parallelizations within the IMM.

Conclusion

We have presented our investigation and evaluation of various shared-memory parallelizations of the data asso- ciation problem in multitarget tracking for general- purpose shared-memory MIMD multiprocessor systems. A sparse measurement database, based on two FAA air traffic control radars, served as the data for our multitar- get tracking problem. We showed that, for sparse multi- target tracking problems, the assignment (or data asso- ciation) problem is not the major computational bottle- neck. Instead, the interface to the assignment problem, namely, computing the rather numerous gating tests and IMM state estimates, covariance calculations, and likeli- hood function evaluations (used as cost coefficients in the assignment problem), is the major source of the workload. Because of the shortcomings associated with previously proposed fine-grained parallelizations of the IMM estimator in a multitarget tracking problem, we proposed a scalable, robust coarse-grained paralleliza- tion across tracks that has excellent performance. Ana- lytically and empirically, we showed that the coarse- grained parallelization has superior execution time per- formance over the fine-grained parallelization for any number of filter models used in the IMM estimator. Furthermore, we showed that the coarse-grained paral- lelization can realize superlinear speedups independent of the number of filter models used in the IMM estima- tor. On the other hand, the performance of the fine- grained parallelization, being dependent on the number of filter models used, yielded negligible throughput for any number of filter models, marginal speedups when many models were used, and worse execution time than sequential time when three or less filter models were used.

Citation

Popp, R., K. Pattipati, Y. Bar-Shalom and R. Ammar, “Shared-Memory Parallelization of the Data Association Problem in Multi-target Tracking,” IEEE Trans. Parallel and Distributed Systems, vol. 8, no. 10, pp. 993–1005, Oct 1997.