NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

Contributors: Jafri, A., Stevenson, J., Kuznar, E. & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

In August of 2018, United States Central Command asked the Strategic Multilayer Assessment Reachback team, How can the United States best increase the resolve and capability of regional actors to get to political reconciliation in Afghanistan? This report highlights the results of NSI’s Interest-Resolve-Capability (I-R-C)™ analysis of Afghanistan stakeholder dynamics.

The I-R-C analysis reveals a stakeholder preference for some kind of stable political settlement (the exception is the ISKP). However, under current conditions, the analysis also suggests that critical stakeholders are divided between two stability outcomes—Enhanced Governance and Brokered Settlement. Sensitivity analyses of stakeholders’ interests ranking reveal that this divide is maintained by the United States as the most resolved and most capable actor in favor of Enhanced Governance over Brokered Settlement. The United States’ preferences were found to be extremely robust; the key factor limiting the United States support of Brokered Settlement is its ongoing, global competition for relative geopolitical influence vis-à-vis China and Russia. For almost all the other actors, a Brokered Settlement is the potential outcome most likely to find broad stakeholder support—or at least avoid direct opposition; besides the United States, those resolved against Brokered Settlement, such as the ISKP and KSA, lack capability to undermine the outcome.

The report concluded that the United States can increase key stakeholder’s resolve in favor of political reconciliation in Afghanistan by prioritizing a Brokered Settlement more than geopolitical influence competition. Our analysis suggests that the United States will still possess high absolute levels of influence capability, though its levels of influence capability relative to Russia and China may be less asymmetrically in its favor. In other words, a cooperative approach which nourishes the rise of other stakeholders’ levels of influence may counter-intuitively better preserve sustainable (and more affordable) options for long-term United States’ influence in the region beyond a two to five-year window.kuz

Vladimir Putin’s Worldview and Perspectives on Space: An Analysis of Public Discourse

Authors: Weston Aviles (NSI, Inc.) and Dr. Larry Kuznar (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

A corpus of Vladimir Putin’s speeches was drawn from his official Kremlin website. The corpus was examined using semi-automated discourse analysis to gauge Putin’s concerns with space and how these are articulated with general political and cultural issues. The primary findings from the discourse are presented as Putin’s perspectives and worldview with respect to the space domain and general themes.

Putin’s Perspectives and Worldview Regarding the Space Domain

• Putin primarily associates space with missile capabilities and deterrence but he also discusses a wide range of other space-related topics including satellite technology and space travel.

• In all cases, these endeavors are developed and executed by the government run company, Roscosmos.

• Putin is beginning to consider the development of a military-industrial complex that would serve both the civilian as well as the government sectors.

• Pride, success and the military are discussed in association with all space themes, indicating a strong, positive emotional connection to space issues.

• Missiles are the most often discussed space topics and are associated with cultural emotive themes such as pride, sacrifice, victory, enemies, and adversaries. This indicates a strong emotional connection and an association with Russia’s enemies.

• Missiles are associated with military operations, troops, and deterrence.

• Putin’s rhetoric regarding satellites reinforces the pride associated with space ventures and also the involvement of civilians and the private and military sectors.

• Pride, success and Russian nationalism are associated with space travel, as is courage and loyalty to Russia for those who venture into space. These are potent sentiments attached to how Putin regards Russia’s space travel.

General Worldview and Values

• Putin’s primary concern, as expressed through thematic density is the Russian economy, followed by the Russian military. The findings of this latest study parallel earlier analyses with respect to Russian influence in Eurasia and the Middle East (Kuznar, 2016b; Kuznar, Popp, & Peterson, 2017a, 2017b; Kuznar & Yager, 2016).

• Russia itself is associated with ominous themes such as competition, danger, and threat.

• The US is involved with themes that have negative connotations such as threat, adversaries, international violations, the Cold War, and economic sanctions.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Authors: Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI, Inc.) and Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Strategic Outcomes in the Korean Peninsula project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Executive Summary

Given the current distribution of actor interests, capabilities and resolve (I-R-C), North Korean denuclearization is highly unlikely without significant change in regional interests and conditions. Under current conditions:

- Neither economic incentives nor threats change the DPRK view of denuclearization –an outcome it can veto.

- I-R-C analysis demonstrates that achieving final and fully-verified denuclearization (FFVD) would require the Kim regime to agree to a path that is detrimental to multiple of its political, security and economic interests. Neither offers of economic and diplomatic rewards (carrots), nor threats of increased regional tension or US military action (sticks) is sufficient to change the North Korean decision calculus enough to make denuclearization appear acceptable from the perspective of the Kim regime. Moreover, North Korea is the single actor with the power to veto denuclearization, i.e., stalling or half-steps result in de facto international acceptance of its nuclear status.

- China is both incentivized and has the ability to undermine FFVD.

- The I-R-C analysis shows both China’s and North Korea’s interests to be better served by

moderate regional tension (as in the pre-summit status quo) than by a US, or South Korean-brokered FFVD. Both also gain more by a drawn-out process of US-DPRK talks that reduce regional tensions but do not make progress on denuclearization. The I-R-C indicates that China’s incentive to undermine FFVD is driven by its interests in gaining regional influence.

- The I-R-C analysis shows both China’s and North Korea’s interests to be better served by

- A US-brokered FFVD of North Korea would require change in core US, Chinese, Russian and DPRK threat perceptions and worldviews.

- US, Russia and China all to prioritize engagement and economic assistance to North Korea (DPRK) over increasing their own regional influence; a broader strategic goal of each.

- Kim regime to radically alter one of its basis for legitimacy away from protecting North Korea from existential threats (through nuclear capability and economic self- sufficiency), toward provision of economic growth and development.

The current US approach to regional leadership may be out-of-touch with regional interests.

- For regional actors, denuclearization is not primarily about security, but about regional stability and influence.

- While no regional actor (other than the DPRK) particularly wants to see a nuclear DPRK, most do not consider DPRK nuclear weapons to be a pressing national security issue or threat. The main DPRK-related threats to regional stability are indirect and have more to do with how others like Japan and the US would respond to North Korean provocations. In fact, concern for their future influence in regional affairs is what drives most regional actors’ preferences with regard to the DPRK nuclear issue. For China and Russia this means containing US regional influence and expanding their own. For South Korea, Australia, and Japan preferences over the issue are driven by their common interests in taking on larger roles in regional security achieved by rules-based multilateral diplomacy.

- Multilateral solutions to regional issues are preferred region-wide.

- he increasingly unilateral US approach to regional issues (such as DPRK

denuclearization) conflicts with the preference of most regional states to work multilaterally and through international law to resolve disputes and increase stability.

- he increasingly unilateral US approach to regional issues (such as DPRK

The success of US efforts to balance China in security matters facilitates growth of Chinese regional influence at the expense of the US.

- China’s strategy of regional economic expansion is a major source of its regional influence which in turn, ensures its own domestic stability and regime legitimacy. Historic US security relationships guarantees, together with regional suspicion of China and Japan have been major source of US regional influence relative to that of China.

- China’s economic growth and influence depends on regional stability, which is reinforced by US security guarantees and assurance of allies suspicious of Chinese intentions. As the region becomes more secure, it becomes more stable. Stability allows states to prioritize economic growth and prosperity. Over time, US security and extended deterrence relationships become less important for insuring a safe and stable region.

How the US approaches this issue may be equally important for its long-term regional interests and influence than whether an agreement on denuclearization is actually achieved.

- For most regional actors, heightened tension and competition for influence between the US and China is a greater threat to their interests than the failure to reach an agreement on DPRK denuclearization.

- US allies and smaller states interests will inevitably be compromised if they are forced to chose between China (critical to their economic interests), and the US (preferred security partner).

- Engaging regional actors through multilateral negotiations would reduce concern over US regional commitment and signal US recognition of the preferences and constraints facing smaller regional states. It would also make it more difficult for China and Russia to act as spoilers than does a bilateral approach.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Strategic Outcomes in the Korean Peninsula project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

The Meaning of ISIS Defeat and Shaping Stability — Highlights from CENTCOM Round 1, 2 and 3 Reach-back Reports.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Conclusion

ISIS will be defeated militarily. However, whether it is ultimately overcome by containment or by deploying ground forces to apply overwhelming force, the path to mitigating violent extremism in the region is a generations-long one. Military options are insufficient to protect US interests and stabilize the region. It will require significant strengthening of State Department and non-DOD capacity to help build inclusive political institutions and processes that protect minority rights in Syria and Iraq. Only if these flourish will ISIS — the organization and the idea it represents — have failed and the region been put on a sustainable path to stability.

Since September 2016 the Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) team has pulsed its global network of academics, think tank scholars, former ambassadors, and experienced practitioners to respond to three rounds of questions by USCENTCOM.3 We received responses from 164 experts from institutions in the US, Iraq, Spain, Israel, the UK, Lebanon, Canada, France and Qatar. 4 The result was 41 individual reach- back reports, each of which consists of an executive summary and the input received from the experts.

This report summarizes key points from the first three rounds of questions. It compiles what the experts had to say about three critical questions: 1) Will military defeat of ISIS in Syria and Iraq eliminate the threat it poses? 2) What are the implications of ISIS defeat for regional stability? and 3) What should the US/Coalition do to help stabilize the region?

[Q1] Are there any contentious space terms or definitions, or are there any noticeable disagreements amongst space communities about appropriate terminologies and/or appropriate definitions for terms? What are the common understandings and uses of space-related terms, definitions, classes and typologies of infrastructure and access? For example, how do we define different classes of space users (e.g., true space-faring states, users of space technology)? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Sabrina Polansky (Pagano) (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

Operationalizing or defining terms is an important first step to understanding concepts, including their boundaries and how they are distinguished from other, potentially related ideas. Similarly, clarity in communication is an essential condition for ensuring that the message or information that is transmitted is as close as possible to what is received. Within the DOD, definitions matter because they are a necessary component for the establishment and application of doctrine. Given the breadth of the space field as a whole, establishing precise definitions may become an even more pressing task, as coordination is sought over a broad base of space sub-communities (e.g., national security space, civil space, and commercial). Each field as a whole and each sub-domain within it naturally has its own terminology, which tends to evolve over time. To best advance coordination within and across the various US and allied space communities, we must be capable of fruitfully combining the work that is being done in various commands, DOD offices, and other agencies and organizations. This can be best achieved when we identify those terms for which precise definitions are required in order to move forward. Doing so also enables the US to avoid any unintended responses from our adversaries. This coordination begins by getting a broad view of the terminological landscape and any terms for which there is current contention.

Drawing on a wide variety of space expert opinions, we identified three different ways in which terms could be contentious. These include: 1) explicitly acknowledged contention, disagreement, or variation in terminology (inherent contention), 2) contention that was not explicitly acknowledged by respondents but discovered through comparison across contributors’ definitions and commentary (emergent contention), and 3) ambiguous terms, which make contention more likely (potential contention). We refer to these different forms of contention collectively as “contentious space terminology.” This assessment is accompanied by an examination of how membership in a given community of space professionals— government, commercial, and analysts4—relates to the kinds of space terms thought to be in contention.

These terminological issues are not necessarily only epistemological in nature, but instead can have important implications for the space field. While not every term in contention will have an obvious or detrimental effect on the ability of the US to operate in or maintain security in space, other terms in contention—such as “space weapons”—may prove problematic for long-term US security interests. As Michael Sherry of the National Air and Space Intelligence Center notes, “Due to the confusion in terminology and misalignment with DOD regular terminology, we have found it difficult in the space community to build systems clearly aligned to a mission.” As such, this report provides a deeper exploration of a set of space terms whose contention may present major security concerns for the US.

Do experts perceive that there is contention in space terminology?

The original question posed began with the assumption that there are common space terms used by different communities of space professionals. To address this, we began by first examining whether there is commonality or variation overall in the terminology that is used, and whether variation occurs as a function of our experts’ professional affiliations.

The majority of subject matter experts (67% overall) indicated directly or indirectly that there is space terminology that is either inherently or potentially contentious. Those working in an analytic capacity (69%)6 or in the commercial domain (69%) more frequently indicated that there is contentious terminology than did subject matter experts working in government. As Colonel David Miller of the US Air Force indicated, “We have tried to come around to using DOD Joint Doctrine as the basis for our terminology, and I think within the Defense Department, we’re pretty good there.” Despite this organizing doctrine, 56% of government respondents (who tended to focus on security) nonetheless indicated that there is contentious space terminology.

Among the current contributors, the most frequent issue contributing to terminology being contentious is its inconsistent use—both across the national security and commercial sectors and within each of these sectors. The variation in use of space terms within the USG is not really surprising given that, as Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor7 of Orbital ATK indicates, the US emphasizes the separation of space into civil (e.g., NASA, NOAA, and USGS) and national security space (e.g., NRO, DARPA, Services) sectors—sub- communities that we might expect would utilize terminology in different ways. On the other hand, Dr. John Karpiscak III of the Army Geospatial Center suggests that differences in the application of a given term could be due to the differences between military branches that primarily ‘own’ versus those who most actively use assets in space (such as the Air Force and the Army). Those working outside of government also observed some variation in the use of terms within the DOD. Referencing Joint Publications and the US Space Policy, Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin noted that,

- the most authoritative DOD documents defining the US national security space lexicon (DODD 3100.10, Space Policy, JP 1-02, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, and JP 3-14, Space Operations) frequently have been inconsistent over the past few decades. Even the definitions of the basic defense space missions have changed frequently.

Ultimately, we cannot assume that everyone—even within a given sub-community working on space—is using the same set of definitions or has the same perspective on space issues given the segmentation inherent to the organization of the US space enterprise, as well as the variation in expertise, topical focus, and concerns of the diverse US space communities.8 This is problematic because it can impede the application of military doctrine, as implied by Sherry’s comments. Moreover, it can potentially hinder collaboration between the US and its prospective allied or commercial partners, leading to inefficiencies.

Contributors in fact offered several specific examples of terms that are contentious. These inputs address both inherent and potential forms of definitional contention, as described above. Additionally, several terms demonstrated emergent contention when variation was observed across the breadth of space expert contributors. To provide an overview of findings, all contentious terms are captured in the table at the end of this summary response. As can be seen from the table, contentious space terms related to security are most numerous, though contention also arises in other instances, such as legal/regulatory. Not all of these terms are necessarily problematic, however. This report thus will focus on examining two terms whose contention has particularly significant implications for national security.

When do contentious terms become problematic?

In many cases, contentious terminology may not matter—or ambiguity may even be desirable

A small minority of experts indicated that variations in terminology simply may not matter. In general, these contributors argued that any discrepancies that might occur could be easily overcome with communication. In addition, some operations may not require precise definitions of terms and/or individuals can resolve or work around them if necessary. Terminological ambiguity might even be desirable as it preserves options, and has, as several current contributors note, been useful to the US in the past when it comes to space issues. Moreover, David Koplow of Georgetown University suggests that attempting to achieve terminological consistency across national lines, public and private lines, and among different space sectors may be misguided; instead, he argues, the focus should be on clearly indicating how terms are being used when they come up, with the understanding that others may use or interpret these terms differently. Though this is likely to be true in many cases—and in particular when working within the US space community or operating alongside allies with whom we would expect this type of coordination—in other cases, it may not be sufficient to wait until an event (e.g., an ASAT test) invokes a potentially related concept (e.g., space weapons) over which different parties may have varying viewpoints.

In other cases, the stakes are high: space weapons and armed attacks

Broadly speaking, contentious terms become problematic when they have the potential to negatively affect the US and its security and other interests. At the more benign end of this spectrum, contentious terminology can lead to inefficiencies and impede collaboration, as noted above. However, at the other end of the spectrum, the stakes are higher, as contentious terminology can lead to misperception of US capabilities or actions among our adversaries, with unintended downstream consequences including escalation and retaliation. There is also the possibility that the US itself will miss or misinterpret its adversaries’ intentions.

To illustrate how this might be so, this report focuses on two examples9 of terminology identified as being contentious—one of which can be broadly categorized as a capability or object (space weapons) and the other which can be categorized as an action (armed attack).

In her discussion of space weapons, Victoria Samson of the Secure World Foundation provides an example of when definitional contention can become important: “…when you talk about security issues, of course the concept of what is a space weapon comes up all the time. The way it could be defined, it could be defined so generally that everything is a space weapon or so strictly that nothing is a space weapon.” This matters because, in the absence of a clearly specified and commonly agreed upon definition, different states may perceive the same capability or object in very different ways based on the way that they are defining a space weapon.

This subjective interpretation contributes to a cognitive bias known as naïve realism—the belief that our perception of the world is the true or correct perception of the world,11 and that others must necessarily see things in the same way (Jones & Nisbett, 1987; Robinson, Keltner, Ward, & Ross, 1995; Ross & Ward, 1996).12 Where one state sees a benign use of a capability, another can see a looming threat—and infer that the other side must therefore intend that threat. The wide application of dual-use space technology13 makes inferring intent from capabilities alone particularly difficult. Unlike the US space sector, in most other states, the private and public space sectors have more permeable—or no—boundaries at all, and neither are there separate civil and military government space sectors.14 Both the organization of space operations and the nature of the technology itself thus increase the possibility that a given state’s intentions can easily be misconstrued. This in turn increases the potential for escalatory or retaliatory behavior when no threat was intended.

This potential for unintended escalation may not yet be fully anticipated in the case of space weapons or weaponization of space, as most experts did not recognize that space weapon (or relatedly, weaponization) was a contentious term. Rather, it was identified as contentious primarily due to the variation in definitions offered by the subject matter experts. Jonty Kasku-Jackson of the National Security Space Institute draws on work by Vasani (2017), noting that the weaponization of space “includes placing weapons in outer space or on heavenly bodies as well as creating weapons that travel from Earth to attack targets in space… [in other words], outer space itself emerges as the battleground.” Brian Weeden of the Secure World Foundation emphasizes the key aspect of space weapons as being intentionally designed to damage, degrade, or destroy another object in space or something on the ground. The type of variation that can be observed here was also indicated directly or indirectly by several contributors (Pollpeter, Samson, Spies, B. Weeden). For example, Michael Spies of the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs indicates that the term space weapon is contested internationally. He discusses the definition of space weapon offered in Article 1 (b) of the draft treaty on the prevention of placement of weapons in outer space,15 noting that the definition does not address terrestrially-based anti-satellite systems (which would, incidentally, be covered under the prior two definitions above). Though there is some cross-over in the definitions offered by the respondents, there is also enough variation among these definitions to suggest that there is not overall coordination among the US space community on this important topic. This is not to say that any one definition is right or wrong—simply that the definitions vary and that this variation has implications. For example, an overall lack of coordination within the US space community on what constitutes a space weapon decreases both the likelihood of coordination with allies and of averting unintended consequences with adversaries.

Similarly, the definition of a space weapon is also likely yoked to the definition of what constitutes an “armed attack,” or relatedly, “[harmful] interference” or the “use of force” in space. As Jack Beard of the University of Nebraska College of Law queries, “Is making a satellite wobble out of its projected orbit an illegal ‘use of force?’ Is it ‘interference’?”16 Having different concepts of where the boundaries of each of these terms lies once again opens up the potential for conflict, and as Beard notes, “what constitutes an armed attack justifying an armed response is a really controversial topic.” At the same time, as Moriba Jah of the University of Texas at Austin indicates, actors such as Russia are strongly in favor of defining terms such as harmful interference, given its interest in invoking “self-defense” in space. As such, the US must balance the need for precision in terminology with the previously indicated utility of ambiguity in serving US interests.

How space weapons and armed attacks are defined also dovetails with another contentious term—outer space. Maintaining ambiguity in the definition and delimination of outer space has generally been strategically useful to the US (B. Weeden). However, defining outer space may matter for security in terms of designating lines of authority, planning, and response. As Patrick Stadter of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory notes,

- if you start to have adversary deploying access that transcend different domains, is it a missile? Does it go into space? At that point, those things become very very important relative to integrated strategic plans and OPLANs and command authority and how that’s reflected in policy. That will matter. It already matters a lot, and it’s a challenge.

Variations in the use of terminology and potential misperception are likely to increase with the widening gap in assumptions, norms, or ideologies that might be observed when different countries come to the table. For example, Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation and Asian Studies Center at the Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, provides some initial insight into how other states may view the issue of space weapons, indicating that the Chinese ultimately think about space and military impact on

space as anything that affects the entire holistic space structure.17 The breadth of this classification of course leaves the door wide open for the perception that the use of a given capability may constitute use of a space weapon, and thus require a response. Thus could begin an escalatory cycle that could be avoided if a common agreement instead is reached regarding what does and does not constitute use of a space weapon or weaponization of space. As it is, Kasku-Jackson notes, there are already some concerns that the US will fold under its definition of “peaceful purposes” (National Space Policy, 2010) both the militarization and the weaponization of space for national and homeland security activities. This fear may make others more likely still to misperceive the use of certain kinds of US capabilities in space as being intended as a space weapon—and thus execute their perceived proportional response.

Conclusion

The true power of definitions lies in their ability to facilitate communication within and across groups and states operating in space and, ultimately, in their ability to facilitate the achievement of US goals, including the maintenace of stability in space. As Brigadier General Thomas Gould (USAF ret.) of the Harris Corporation indicates, the US should aim to provide leadership in the definition of norms (and presumably, associated space terms). This view was echoed by Samson, who notes that norms and international cooperation may be the best route by which to achieve stability and predictability in space, with reliable access to space assets. In the case of space weapons, a failure to establish common definitions and associated norms can result in misperceptions that can leave the US and other space actors in a precarious position. Samson cautions, however, that by talking about space weaponization, the conversation is led down a road that may not be necessary or helpful. Instead, she argues, it may be more helpful to talk about stability, which is “a broader concept that contextualizes the domain and allows you to talk about anything that destabilizes the space domain.” Thus, by having a broader understanding of the array of things for which space is actually used, she argues, we might more readily disambiguate some of these points of confusion or contention.

Contributors

Roberto Aceti (OHB Italia, S.p.A. a Subsidiary of OHB, Italy); Adranos Energetics; Brett Alexander (Blue Origin); Anonymous Commercial Executives; Anonymous US Launch Executive; Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Brett Biddington (Biddington Research Pty Ltd, Australia); Bryce Space and Technology; Caelus Partners, LLC; Elliott Carol3 (Ripple Aerospace, Norway); Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Matthew Chwastek (Orbital Insight); Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (ret.) Deron Jackson (USAFA); Faulconer Consulting Group; Jonathan Fox (Defense Threat Reduction Agency); Joanne Gabrynowicz (University of Mississippi School of Law); Dr. Nancy Gallagher (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Harris Corporation; Dr. Jason Held (Saber Astronautics, Australia); Dr. Henry Hertzfeld (George Washington University); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Jonathan Hung (Singapore Space and Technology Association, Singapore); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Dr. John Karpiscak III (US Army Geospatial Center); Jonty Kasku-Jackson (National Security Space Institute); Dr. T.S. Kelso (Analytical Graphics Inc.); David Koplow (Georgetown Law); Group Captain (Indian Air Force, ret.) Ajey Lele (Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, Centre on Strategic Technologies, India); Dr. Martin Lindsey (US Pacific Command); Agnieszka Lukaszczyk (Planet, Netherlands); Elsbeth Magilton (University of Nebraska College of Law); Colonel David Miller (United States Air Force); Dr. George C. Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Kevin Pollpeter (CNA); Victoria Samson (Secure World Foundation); Matthew Schaefer and Jack Beard (University of Nebraska College of Law); Michael Sherry (National Air and Space Intelligence Center); Brent Sherwood (NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory); Michael Spies (UN Office for Disarmament Affairs); Dr. Patrick A. Stadter (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory); Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; Dr. Mark Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); John Thornton (Astrobotic Technology); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska); Deborah Westphal (Toffler Associates); Dr. Brian Weeden (Secure World Foundation); Charity Weeden (Satellite Industry Association, Canada); Joanne Wheeler (Bird and Bird, UK)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q9] What are the biggest hindrances to a successful relationship between the private and government space sectors? How can these be minimized? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

The 33 individuals or teams that provided input represent large, medium, and small/start-up space companies; 4 USG civil space agencies; academia; think tanks; and professional organizations. Four of these are non-US voices (Australia, Canada, Italy, and Norway.)

The consensus view among the expert contributors to this report is that a successful and sustained government- commercial relationship in the space domain is as essential for achieving US national security goals as it is for achieving commercial profits.5 At present, however, contributors see the ways in which US civil and National Security Space (NSS) operate as barring the attributes that make for an attractive business environment, including: a) clear requirements and data exchange between government and commercial partners, b) persistent and predictable funding and cash flow, c) non onerous and consistently implemented export controls, and d) synchronization of internal government agendas and decision making with regard to space.

The following sections discuss four themes related to US public and private space sector relations (i.e., US civil and National Security Space and the commercial sector) that emerge in the input provided by the expert contributors. While one of the themes focuses on positive aspects of the relationship, the other three themes focus on types of barriers—namely, red tape, culture, and organization of the bureaucracy. The frequency of mentions for each of these themes, as well as for specific examples of each given by the contributors, is summarized in the Figure below. These themes are discussed in greater detail below. It should be noted that, unless specified, there was no association between an expert’s views and his or her professional affiliation. The barriers and mitigation options discussed here were identified as much by NSS and US civil space voices as by commercial and scholarly ones.

First, the Good News…

Although the question of focus prompted experts to address hindrances, nearly a third (30%) of the contributors feel that relations between US public and private space sectors are fairly good. In fact, even among contributors who see significant barriers, several identify specific organizations and programs as exemplars of ways to make USG space a more attractive and accessible business environment.6 NASA is the governmental organization that is most frequently cited as having made progress in cutting red tape and developing innovative ways to work with commercial actors. The FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation is the second most cited, followed by NOAA and then finally, some programs at NGA.7

The Barriers

The majority (70%) of expert contributors mentioned at least one of three types of important barriers that hinder relations between the commercial sector and US National Security Space. “Red Tape” refers to barriers imposed by USG regulatory and acquisition/contracting processes. “Culture” captures barriers that contributors suggest arise from the different goals, expectations, and cultures of the NSS and commercial space communities. Finally, “Organization of Bureaucracy” addresses impediments that result from the organization and structure of the US bureaucracy.

#1: Red Tape

What are described as opaque, convoluted, and slow US regulatory and acquisition/contracting processes are the hindrances that are most frequently mentioned by contributors.

The Barriers

In a sentiment echoed by other contributors, Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor of Orbital ATK suggests that problems with space acquisition do not just reside within bureaucratic machines, but often emerge at the outset from “a poor requirements process—[the NSS] can’t decide what it wants.” Dr. George C. Nield of the Federal Aviation Administration offers a reason for why this is so: “the nature of the DOD organizational structure, namely lots of people can say ‘no,’ but no one’s empowered to say ‘yes’.”

What is the impact on the commercial sector? In short, the effect is increased costs of doing business with NSS. When acquisition and contracting processes are difficult to navigate, involve so many steps, and require extended periods to reach contract award, the transaction costs of working with the USG can become higher than the value of the work itself—a negative business case that is extremely difficult to defend to shareholders and investors. Lengthy periods of uncertainty involved in securing work with NSS also increase financial risk to companies who must spend up-front capital to pursue NSS work.8 Smaller companies may experience additional barriers. Three contributions from small or start-up businesses find that current acquisition processes may benefit “entrenched interests” and make it difficult for smaller firms to compete with larger, better-known prime contractors.9 Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland sees the issue as reciprocal—that is, the “creakiness/complexity of the acquisition process at DOD and NASA” also makes it harder for the USG to find and work with smaller companies.

While contributors were sympathetic to the necessity of government oversight of dual-use technologies with national security implications, many believe that this oversight is overly restrictive, unfair to US firms, and/or prone to what Joshua Hampson of the Niskanen Center tags as the “capriciousness and opaqueness” of decisions about export controls.10 More than half of the expert responses mention inconsistently implemented, “burdensome” and/or “outdated” mandatory Federal Acquisition egulation (FAR) requirements, International Traffics in Arms Regulation (ITAR), and other compliance requirements as major barriers to successful relations between public and private sector space. There are two inevitable results of restrictive export controls. First, activities such as moving space- related items from general export controls to ITAR put US companies at a disadvantage relative to foreign competitors, and create a situation that eventually will incentivize companies to leave the US for areas with more lenient controls.12 Second, as Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy) argues, a restrictive environment invites competition from foreign governments eager to attract business away from the US.

#2: Cultural Differences

What experts saw as “cultural” barriers to government-commercial partnerships in the space domain were attitudes and behaviors rooted in the different agendas, priorities, motives, incentive structures, and varying speeds of operations of government and commercial space. Contributors described two specific sources of culture clashes: differences in expectations about the operational environment, and different concepts of information sharing and control.

One critical difference between government and commercial space, unsurprisingly, emanates from the varying operational environments in which each side finds itself. In one example, Hampson observes that the private- and public-sector funding environments “do not neatly overlap.” He points out that even small changes in program funding can strain relations between the government and the private sector. Pressure on businesses to produce revenue—or at least the real possibility of it—to investors and directors as quickly as possible can be stymied by the deliberate pace of the NSS funding processes and decision cycles. In addition, government planning on the single fiscal year is simply out of alignment with commercial investment planning which, by necessity, requires longer lead times (e.g., for staffing- up, engaging capital investment, etc.) than does government planning. This mismatch can be lethal to all but the largest and most mature firms. For smaller, or “new space” innovators, this discrepancy can “de- incentivize entering the market or working with the US government” (Hampson).13 Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy)14 concurs that misunderstanding of commercial funding requirements is a major reason that companies often do not even consider the USG in their business planning. Simply put, the NSS business environment is too slow and thus too risky for the “aggressive go-to-market” strategies that drive many of these privately-funded enterprises.

A number of experts remarked on barriers generated by government versus commercial expectations regarding the control of all facets of space capabilities, systems, and development. An area in which the government culture of “control” appears particularly harmful is the control of information. This includes what experts identified as the tendency of NSS organizations to expect unidirectional information flows from commercial to government but not the other way around. Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Jackson (United States Air Force Academy) and Victoria Samson (Secure World Foundation) are critical of the government’s lack of transparency and tendency for “over-classification” of space-related information. As an example of the former, Dr. T.S. Kelso of Analytical Graphics, Inc. recounts his experience with tracking data disseminated by the Joint Space Operations Center (JSPOC) to commercial space; he notes that this data often is delayed, of questionable veracity, and/or incomplete. He says, “we constantly run into this kind of situation where the government is trying to protect processes or capabilities or systems or whatever it happens to be…but at the same time, we are putting hundreds of satellites that DOD relies on for things like communications at risk because we could think we understand the situation and actually maneuver into a collision rather than avoid one.” In a similar vein, the ViaSat, Inc. team comments on a recent statement by the Secretary of the Air Force on barring proprietary interfaces with government systems. They argue that declarations such as these illustrate a key government misunderstanding of the commercial sector, and should be the foci of efforts to find mutually beneficial common ground.

Nield describes the USG as committed to a “deeply ingrained habit of doing things the way we’ve always done them.” A number of experts identify the ironic result: The standard steps taken by the government to protect NSS systems could generate increased risk to those assets; an effect that these experts expect will only worsen as the space environment becomes more crowded. Contributors argue that ultimately, the key difficulty to overcome in the name of partnership is the reluctance of the NSS community to amend its standard procedures for fear of yielding control to other elements of the USG or the commercial sector.

Dr. Edythe Weeks of Webster University offers a slightly different view of the impact of culture clashes between public and private sector space. Rather than taking sides—or assigning the government most of the blame—Dr. Weeks characterizes the (ultimately self-defeating) conflict between the “myths” of commercial versus government space as one over “who knows the best way.” Commercial space, she argues, believes that it can produce space capabilities smaller, better, and faster than can government space. Given this ethic, it is not surprising to uncover commercial sector frustrations with a government space enterprise that it perceives as following a slower, less effective path. This commercial-government ‘mythology,’ encourages commercial space and the US public to “forget” the significant role played by the government in setting the legal conditions, funding innovative research and development, and purchasing services that underwrite commercial space. The mythology also diverts Congressional attention from the critical role of US government space, with the ironic effect of reducing budget appropriations for public sector space programs. This creates a negative cycle which lies at the heart of much of the budget uncertainty about which commercial actors complain.

#3: Bureaucratic Organization and Structure

The final category of hindrances mentioned by contributors has more to do with the practices and structure of the federal government than with the DOD or the NSS, specifically. Key issues mentioned by the expert contributors were the insufficient staffing and underfunding of US government space as a whole, as well as the legal requirements and other elements of the NSS acquisition process that are outside direct DOD input or control. Examples of the latter include the particularities of Congressional processes that can cause unanticipated roadblocks in program funding; or White House policy and priority changes that can change significantly from one election to the other. Robert Cabana of the NASA-Kennedy Space Center cites deficient policy synchronization among USG space agencies as adding to the confusion felt by firms that may want to do business with the USG. Hitchens in turn identifies the “lack of a clear policy on export controls [as] slowing the licensing process” for commercial space. Finally, Faulconer Consulting Group15 argues that many of the issues are the result of not having clearly established the government’s role relative to commercial space, asking, “Is the US Government client, manufacturer, or regulator?” They further point out the source of conflict: As one of the largest potential investors in the space sector, work done by government agencies is often in direct competition with “what the commercial providers can provide,” while at other times, the government is “purely the customer purchasing commercial services.”

Actions to Minimize Hindrances

If it is agreed that fostering a healthy, globally competitive commercial space sector is not at odds with US national security requirements but is itself a key requirement, then middle ground solutions must be found. To do so effectively requires taking an accounting of where the points of tension are. As such, tensions between commercial and government requirements, together with some steps for mitigating each, are summarized in the table below.

Contributors mentioned the need to “streamline,” “update,” and “reform” both acquisition and regulatory practices by taking steps to make them more transparent, lowering transaction costs to businesses associated with lengthy proposal writing and processing times, and facilitating access to businesses beyond the “old space” firms with which the NSS community currently partners. The majority of recommendations involved expanding the sizes and types of solicitations and funding vehicles available for space acquisition (e.g., increased use of Broad Agency Announcements [BAAs]; Small Business Innovation Research awards [SBIRs]; fixed-price contracts, competitions, demonstrations, and prizes; and space act agreements) to allow the government to leverage private sector investment and capabilities while reducing bureaucratic costs.16 Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin offers several suggestions to facilitate progress, including increasing funding for federal regulatory agencies so that they might be fully-staffed, offering workers incentives for good performance, and modifying personnel policies to attract the best talent to the USG.

Contributors

Adranos Energetics; Brett Alexander (Blue Origin); Anonymous Commercial Executives; Anonymous Launch Executive; Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Bryce Space and Technology; Robert D. Cabana (NASA-Kennedy Space Center); Caelus Partners, LLC; Elliot Carol3 (Ripple Aerospace, Norway); Chandah Space Technologies; Matthew Chwastek (Orbital Insight); Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy); Faulconer Consulting Group; Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Michael Gold (Space Systems Loral); Joshua Hampson (Niskanen Center); Harris Corporation, LLC; Dr. Jason Held (Saber Astronautics, Australia); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, University of Maryland); Dr. T.S. Kelso (Analytical Graphics, Inc.); Sergeant First Class Jerritt A. Lynn (United States Army Civil Affairs); Dr. George C. Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Jim Norman (NASA Headquarters); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Victoria Samson (Secure World Foundation); Spire Global, Inc.; Dr. Patrick A. Stadter (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory); Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; Dr. Mark J. Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); John Thornton (Astrobotic Technology); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska College of Law); Charity Weeden (Satellite Industry Association, Canada); Dr. Edythe Weeks (Webster University); Deborah Westphal (Toffler Associates)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Integration Report: Gray Zone Conflicts, Challenges, and Opportunities.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) requested a Strategic Multilayer Assessment effort “to determine how the USG can identify, diagnose, and assess indirect strategies, and develop response options against associated types of gray zone conflicts.” This integration report provides a synthesis of all the team projects. Their work has advanced understanding of the contours of the gray zone terrain, and the challenges inherent in navigating that terrain. By identifying the critical features of the gray zone, their findings also provide a guide to where USSOCOM and other DOD entities should focus future efforts in this area to facilitate the development of operational level planning and response strategies. The key results of the effort fall into four areas as summarized below.

What is the nature of gray zone conflict?

- There is no single condition that can identify an action as gray, independent of actor or understanding of the broader strategic context

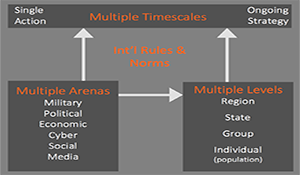

- We need to think on multiple timescales, across multiple arenas (e.g. political, social, economic), and understand and engage with multiple social levels (state, group, individual)

- Populations are the key dimension in gray zone conflict

- Norm violations help define the threshold between ordinary competition and the gray zone

What motivates actors to engage in gray zone activities?

- Successful US deterrence has not eliminated the motivations of other actors to further their own interests

- Acting in the gray zone is an effective low risk, low cost strategy that has proven difficult for the US and partner nations to counter, and for vulnerable states to defend against

- US military places primacy on physical maneuver, and our adversaries know this

How should the US respond to gray zone activities?

- Incorporate the human / cognitive domain

- Think and plan beyond kinetic responses alone; expand DOD definitions of maneuver and objective to account for the human aspects of military operations

- Shape the international environment to reduce the motivations for engaging in gray zone activities

- Develop a clear, compelling strategic narratives

- Provide alternative narratives and leverage social and mass media to communicate them

- Build trust and credibility with partner nations to enable unity of effort

- An enduring, proactive presence and consistent messaging across all USG agencies is a significantly superior approach to taking select actions in response to specific gray actions

- Scope and timing of US response matters

- Inaction in the face of low level actions (e.g. Chinese Island building in the SCS) can over time create a “new reality” that threatens US interests and security

- Early and effective response to gray actions and strategies requires a consistent US presence

- Focus now should be less on defining specific actions as gray zone threats, and more on how to leverage all instruments of national power to respond to them

What capabilities does the US need to respond effectively to gray zone activities?

- Human/Cognitive Domain Information & Expertise

- Gray zone strategies exploit multiple instruments of power. Operating in this environment requires information across all of these instruments

- Conceptual Models and Frameworks

- Scope of gray zone activities will make information requirements overwhelming without models to guide search and interpretation

A Cognitive Capabilities Agenda: A Multi-Step Approach for Closing DOD’s Cognitive Capability Gap.

Author | Editor: A. Astorino-Courtois (NSI, Inc,).

Executive Summary

The Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) team conducted a year-long project for USSOCOM on the growing prevalence of Competition Short of Armed Conflict (CSAC), or use of “Gray Zone” tactics by US adversaries. Key findings from the study include first, the immediate need to incorporate the “human / cognitive domain” into military planning to avoid the strategic surprise that gray zone tactics intend. Second, the study highlighted the current deficit in the joint force of operationally-applicable human / cognitive domain information and expertise. During its final project review, the study’s Senior Review Group (SRG) noted that “…the changing nature of conflict means that the US Department of Defense (DOD) needs to start changing the way it thinks as a whole, and the results of this SMA effort can play a valuable role” in broadening our understanding of the strategic and operational environment to incorporate the human/cognitive aspects of military operations. Reflecting on the deficit in US capabilities in the cognitive environment the SRG asked: “Who is going to craft the appropriate messages? Who is going to provide the necessary tools? Who is going to use these tools? These are questions that we need to answer.”

This s white paper is a brief effort to suggest an initial outline that might be undertaken to address these questions.

Contributors

CAPT Joseph A. DiGuardo, Jr. (Joint Staff J39), Dr. Hriar Cabayan (Joint Staff J39); Mr. Michael Ceroli (USASOC); Dr. Rebecca Goolsby (ONR); Mr. Robert Jones (USSOCOM); Dr. Spencer Meredith (NDU); Mr. Randy Munch (TRADOC G-2); Dr. Laura Steckman (MITRE), Dr. Robert Taguchi (USASOC); LTC Scott Thomson (OUSD-P)

Author | Editor: Popp, G. & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

This report represents the views and opinions of the participants. The report does not represent official USG policy or position.

At the request of United States Central Command (USCENTCOM), the Joint Staff (JS), and jointly with other elements in the JS, Services, and US Government (USG) Agencies, the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) team established a virtual Reach Back Cell. This initiative, based on the SMA global network of scholars and area experts, has provided USCENTCOM with population based and regional expertise in support of ongoing operations in the Iraq/Syria region. This Panel will discuss the main findings from the SMA Reach Back Cell.

Panel members:

- Ms. Sarah Canna (NSI), moderator

- Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI)

- Dr. Munqith M. Dagher (IIACSS)

- Dr. Jen Ziemke (John Carroll University)

- Dr. Ian McCulloh (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory)

- Dr. Diane Maye (ERAU)

- Dr. Laura Steckman (MITRE)

- Ms. Tricia DeGennaro (TRADOC G-27)

- Dr. Jon Wilkenfeld (University of Maryland)

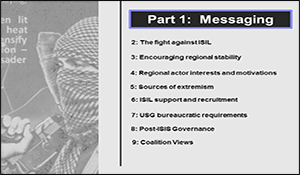

SMA CENTCOM Reach-back Reports – Part 1: Messaging.

Author | Editor: SMA Program Office.

This is Part 1 of a 9 part series of SMA Reach back responses to questions posed by USCENTCOM. Each report contains responses to multiple questions grouped by theme.

At the request of United States Central Command (USCENTCOM), the Joint Staff, jointly with other elements in the JS, Services, and U.S. Government (USG) Agencies, has established a SMA virtual reach-back cell. This initiative, based on the SMA global network of scholars and area experts, is providing USCENTCOM with population based and regional expertise in support of ongoing operations in the Iraq/Syria region.

The Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) provides planning support to Commands with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are NOT within core Service/Agency competency. Solutions and participants are sought across USG and beyond. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff and executed by ASD(R&E)/EC&P/RRTO.

Responses were submitted to the following CENTCOM Questions:

- What are the predominant and secondary means by which both large (macro-globally outside the CJOA, such as European, North African and Arabian Peninsula) and more targeted (micro- such as ISIL-held Iraq) audiences receive ISIL propaganda?

- What are the USCENTCOM and the global counter-ISIL coalition missing from counter-messaging efforts in the information domain?

- What must the coalition do in the information environment to achieve its objectives in Iraq and Syria and how can it deny adversaries the ability to achieve theirs? – Part 1

- What must the coalition do in the information environment to achieve its objectives in Iraq and Syria and how can it deny adversaries the ability to achieve theirs? – Part 2

- The response to QL5 noted that ISIL is moving to ZeroNet platform for peer-to-peer messaging, which is extremely robust to distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attack/other counter measures. What effect could this have on Intel efforts?

- The wide-spread, public access to smartphones has been a game-changer for the distribution and production of propaganda. Is there more data available about the types of apps (e.g., WhatsApp, Facebook, Telegram, Viber) used on smartphones to distribute propaganda, and the methods through which this is accomplished?