NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

Violent Non-state Actors in the Gray Zone A Virtual Think Tank Analysis (ViTTa).

Author | Editor: Sarah Canna, Nicole (Peterson) Omundson, & George Popp (NSI, Inc.)

Using the Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) expert elicitation methodology, NSI asked six leading gray zone experts whether Violent Non-state Actors (VNSAs) belong in the definition of the gray zone. However, experts were reticent to answer this question; they thought the question missed the point. The focus should not be how to define the major threats that are facing the USG, but rather how to leverage all instruments of national power to respond to them. When pushed to answer the original question, experts largely conceded that VNSAs, by themselves, do not rise to a level of significant threat in the gray zone, but are key tools used by state actors to achieve their ends. They concluded by identifying other challenges and solutions facing the USG in the gray zone.

In January 2016, General Joseph Votel (US Army) requested that the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) office examine how the United States Government (USG) can diagnose, identify, and assess indirect strategies, and develop response options against, associated types of gray zone challenges. More specifically, the request emphasized that if the USG is to respond effectively to the threats and opportunities presented in the increasingly gray security environment, it requires a much more detailed map of the gray zone than it currently possesses. One core question raised by General Votel was whether violent non-state actors (VNSAs), like violent extremist organizations (VEOs) and transnational criminal organizations (TCOs), fit into the definition of the gray zone.

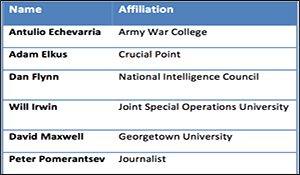

To respond to this question, NSI applied its Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) expert elicitation methodology to the problem set. As part of this effort, NSI interviewed six leading gray zone experts (see Table 1 and Appendix A) on whether, and under what conditions, VNSAs rise to a level of significant threat in the gray zone.

Their answers surprised us.

We Asked the Wrong Question

We initiated this effort with the objective of defining when and under what conditions VEOs and TCOs fit into the definition of the gray zone. However, experts were reticent to answer this question; they thought the question missed the point. The focus should not be how to define the major threats that are facing the USG, but rather how to leverage all instruments of national power to respond to them.

However, despite challenging the premise of the question, David Maxwell suggested that exercises like this one are useful not so much in determining the “right answer,” but rather to engage in a meaningful discussion that will help the nation better assess the challenges it faces, develop effective courses of action, and formulate plans to achieve key objectives. “Ultimately, the focus should not be on whether or not a conflict should fall into the gray zone. The US tends to try to organize everything into a clear category or create a clear label for everything,” Maxwell stated. The gray zone is ambiguous and complex, and is not suited to clear, crisp definitions.

Similarly, Adam Elkus noted that although the US would like to develop a clear dividing line between conflict and competition including who can engage in gray zone activities, other countries (primarily non-Western ones) do not think about achieving state objectives in this way. That makes it easier for them to exploit US relations without severe repercussions. Despite these reservations, we did ask the experts to respond to the original question.

The Characterization and Conditions of the Gray Zone: A Virtual Think Tank Analysis (ViTTa)

Author | Editor: Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

Within United States government (USG) and Department of Defense (DoD) spheres, the gray zone is a relatively new terminology and phenomena of focus for characterizing the changing nature of competition, conflict, and warfare between actors in the evolving international system of today. Accordingly, in January 2016, General Joseph Votel (US Army) requested that the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) team conduct a study of the gray zone. The SMA team was asked to assess how the USG can diagnose, identify, and assess indirect strategies, and develop response options against associated types of gray zone challenges. More specifically, the request emphasized that if the USG is to respond effectively to the threats and opportunities presented in the increasingly gray security environment, it requires a much more detailed map of the gray zone than it currently possesses.

To properly conduct any effort focused on researching, understanding, and assessing this gray zone space, it is imperative to first ensure that the effort is using sound, appropriate, and comprehensive definitions—to effectively assess the gray zone, one must appropriately define the gray zone. The importance of proper definitions is particularly relevant when it comes to the study of the gray zone, which is an inherently ambiguous concept in itself and has a number of varying definitions already in existence.

Recognizing the importance of properly characterizing and defining the gray zone concept, the SMA team put significant effort into developing a sound, comprehensive definition of the gray zone. Through a series of panel discussions and intense inter-team discussions, and with the assistance of a white paper on the topic, the SMA team, in conjunction with USSOCOM, developed the following definitions for the gray zone, gray zone activity, and gray zone threats.

The gray zone is a conceptual space between peace and war, occurring when actors purposefully use multiple elements of power to achieve political-security objectives with activities that are ambiguous or cloud attribution and exceed the threshold of ordinary competition, yet fall below the level of large-scale direct military conflict, and threaten US and allied interests by challenging, undermining, or violating international customs, norms, or laws.

Gray zone activity is an adversary’s purposeful use of single or multiple elements of power to achieve security objectives by way of activities that are ambiguous or cloud attribution, and exceed the threshold of ordinary competition, yet apparently fall below the level of open warfare.

- In most cases, once significant, attributable coercive force has been used, the activities are no longer considered to be in the gray zone but have transitioned into the realm of traditional warfare.

- While gray zone activities may involve non-security domains and elements of national power, they are activities taken by an actor for the purpose of gaining some broadly-defined security advantage over another.

Gray zone threats are actions of a state or non-state actor that challenge or violate international customs, norms, and laws for the purpose of pursuing one or more broadly-defined national security interests without provoking direct military response.

- Gray zone threats can occur in three ways relative to international rules and norms, they can:

- challenge common understandings, conventions, and international norms while stopping short of clear violations of international law (e.g., much of China’s use of the “Little Blue Men”);

- employ violations of both international norms and laws in ways intended to avoid the penalties associated with legal violations (e.g., Russian activities in Crimea); or

- violent extremist organizations (VEOs) and non-state actors integrating elements of power to advance particular security interests

In an effort to validate the SMA team’s definition of the gray zone, NSI applied its Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) subject matter expert elicitation methodology to the problem set. As part of this ViTTa effort, NSI interviewed leading gray zone experts to better understand the characterization and conditions of the gray zone, putting particular emphasis on having the experts assess the SMA team’s gray zone definition. NSI recorded and transcribed the interviews, which formed the basis of this report. The goal of this report is to present the experts’ insights relating to the characterization and conditions of the gray zone and, in particular, highlight expert feedback, insight, and commentary regarding the SMA team’s gray zone definition.

Contributing Authors

Canna, S. (NSI)

Question (R4.3): To what extent is the Iraqi Army apolitical? Do they have a political agenda or another desired end- state within Iraq? Could the Iraqi military be an effective catalyst for reconciliation between different groups in Iraqi society? Could conscription be an accelerant for reconciliation and if so how could it be implemented?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

The subject of this report touches on a critical issue for the future of Iraq as a unified and stable state: To what degree will the Iraqi Armed Forces be able to serve as the vanguard for resurrection of national identity and tolerance? If the answer is not at all, Iraq as a single independent state is likely doomed.

To address the question posed, many of the expert contributors to this Reach-back report begin with an important observation: the Iraqi Army, like other public institutions around the world, is not a unitary actor with a single political orientation, agenda, or desired end- state. Like other militaries, it mirrors the social conditions and pressures of the population from which it comes. For the Iraqi Army, this means the ethno-sectarian divisions, pervasive corruption, and well-ensconced patronage and power networks that work around and despite military rank or process.

How did the Iraqi Armed Forces get to this point?

A number of the contributors point to the turbulent history of the Iraqi Armed Forces (IAF) as the foundation of its current condition. Hala Abdulla of the Marine Corps University dates the beginning of the deterioration of its professionalism and strength to the Saddam Hussein era, when Saddam assassinated senior leaders that he perceived as threats to his control. Over time, this practice meant that the cohort of professional leaders who might have enjoyed broad popular and military regard had been decimated. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by Coalition forces continued the weakening of the Army as an institution. Importantly, that invasion also had the critical effect of drastically changing the sectarian make-up of the Army leadership from Sunni to Shi’a- dominated; a process that was accelerated under the leadership of Nouri al Malaki. Abdulla argues that the post-2003 Army was weaker than the pre-2003 Army reflecting the fragmentation of society, along with rampant corruption and nepotism.

Does the Army have a political agenda? Not exactly.

The contributors to this report each argue that the Iraqi Army is far from apolitical, but importantly, that this fact is the result of the Army’s demographics rather than its partisanship. Dr. Elie Abouaoun of the US Institute of Peace cautions that we take care in thinking of the Army as a “monolith” with a single set of political views. It is because the force is overwhelmingly Shi’a that it naturally reflects the political and social concerns of the Shi’a-led government and communities.

The experts also agree that the Army does not have its own political agenda or cohesive image of the future of the Army or Iraq. Rather than any political orientation in fact, Middle East scholar Shalini Venturelli’s (American University) research identifies the strongest guiding principle in the Army as preservation of individual and group power and influence. This is done in the Army via the same types of social and familial patronage and influence networks found in the rest of the country. It is this urge and the dynamics of competing hidden power networks within the Army that has stymied its re-professionalization and accounts for the corruption and nepotism with which it is plagued.

Could the Army or Special Forces serve as a force for national reconciliation? No way, unless …

There is wide agreement among the authors regarding the prospect that the Iraqi Army could be a catalyst for national reconciliation: they are dubious at best. Wayne White of the Middle East Institute points out that, in its current guise, the “largely Shi’a force sometimes [has been] in league with abusive militias” and, though the Iraqi Army that fought Iran was more than half Shi’a, the years of ethno-sectarian conflict have embittered many in the Army against Sunni, Turkoman, Kurdish, and other groups. Elie Abouaoun (USIP) explains that “solidarity” among some military units might develop, but “the institutional bonding is not strong enough to overcome the vertical divisions along ethnic and sectarian lines.”

The two areas where the experts disagree are: 1) whether the Army’s successful performance in Mosul has rehabilitated its reputation among minority populations; and relatedly, 2) the degree to which the US-trained Iraqi Special Forces (Golden Divisions) that make up a large part of the Mosul force might serve as a model for professionalizing the larger force and catalyzing national regard for the military. Bilal Wahab (Washington Institute for Near East Policy) and Muhanad Seloom (ICSS, UK) believe that the “highly professionalized” Special Forces have “boosted a sense of nationalism” in Iraq and have significantly improved popular perception of forces that not too long ago were seen not as Golden, but as the “Dirty Division.” Yerevan Saeed (Arab Gulf States Institute) and Macin Styszynski (Mickiewicz University, Poland) observe little change in Sunni or Kurdish views of the Iraqi Army, primarily they argue, because these populations observe little change in the Army—which looks very much like the organization until very recently responsible for “widespread abuse, violence and human rights abuses.” Shalini Venturelli (American University) believes that even if there was improved popular regard for the Special Forces, the exceptionalism of the Golden Division is overstated, and that withdrawal of US trainers and support elements would rapidly show these units to be bound by the same corruption and competing power networks as the larger force.

Although highly skeptical of these occurring any time soon, the experts do offer conditions under which the Iraqi Army might eventually serve as an engine of national reconciliation. The most critical of these is (re)gaining popular trust in both the Government of Iraq and the military that serves it. The only way to overcome popular perception of the Army’s Shi’a favoritism is through sincere political reform in which “Sunnis have a major strategic stake” and are convinced of the government’s “enduring commitment to their security regardless of which party(ies) hold the reins of power” (Shalini Venturelli, American U.) Even if there were to be a professionalized, unified Iraqi Army some time in the future, Zana Gulmohamad of Sheffield University forecasts that “the reconciliation will be partial, and not include the entire country,” but instead be limited to Iraqi Arabs (Shi’a and Sunni). The Kurds, he argues, have their own security forces that they will always trust more than the Iraqi Army.

Is conscription a good idea? Not likely.

None of the expert contributors to this report sees conscription into the Iraqi military as a viable path to reconciliation. In fact, some suggest under current conditions military conscription could very easily deepen rather than reduce the ethno-sectarian tensions that wrack the country. While he allows that, “enrolling in the army—including conscription—might ease up inter-personal relations somehow,” Elie Abouaoun contends that the effect does not scale because Sunni “collective fears” of the Army remain. He points to Lebanon’s experience with using compulsory military conscription to encourage national identity among its warring sectarian groups. The failure to enact political reforms, he says, was a major cause of the lackluster results: “failing to embrace an inclusive governance model undermined the possible—though highly unlikely— impact of such efforts. Iraq is not different, especially with the presence of tens of thousands of fighters now enrolled in militias.”3 Again, the military reflects the nation.

The point is this: prior political reform and social integration are not just important facilitators for development and professionalization of the Army and thus its value as a platform for national identity and reconciliation—they are required pre-conditions. Neither the current Government of Iraq nor the Army is likely to succeed in stabilizing the country until Sunni Arabs and other minority populations are integrated into the state’s political, security and social institutions. As Wayne White of the Middle East Institute cautions, if this is ignored, Sunni resistance will persist. Finally, Shalini Venturelli reminds us that, even if these reforms have been made, restoring the trust of Sunnis, Kurds, and other minority groups in the national Army is a decades-long process.

Contributing Authors

Hala Abdulla (Marine Corps University); Dr. Elie Abouaoun (US Institute of Peace); Dr. Scott Atran (ARTIS Research); Zana Gulmohamad (University of Sheffield, UK); Yerevan Saeed (Arab Gulf States Institute); Dr. Muhanad Seloom (Iraqi Centre for Strategic Studies, ICSS, UK); Dr. Marcin Styszynski (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland); Dr. Shalini Venturelli (American University); Dr. Bilal Wahab (Washington Institute for Near East Policy); Wayne White (Middle East Institute)

Author | Editor: Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The Physical Defeat of ISIS video addresses if a physical defeat of ISIS fully eliminate the threat it poses? Highlighting some of the work NSI has conducted as part of a Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) team Reach Back Cell in support of USCENTCOM, this video discusses the future of ISIS.

How Discourse Analysis Could Help Provide Insight into the Future of US-China Relations.

Author | Editor: Dr. Lawrence Kuznar, Nicole (Peterson) Omundson, & George Popp (NSI, Inc).

The future of the US-China relationship seems increasingly uncertain, to say the least. Increased tensions between the two international powers were seemingly ignited when US President Donald Trump (President-elect at the time) engaged in a telephone call with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen on 2 December 2016. The telephone call was a notable event, as it is believed to be the first reported official telephone communication between a Taiwanese president and US president (or president-elect) since the establishment of US-Beijing diplomatic relations in 1979.

Not surprisingly, the US-Taiwan telephone call did not sit well with Chinese leadership, who were quick to express concern. In fact, this conversation instigated a chain of back and forth commentary and provocative gray zone actions between the US and China, a softening of language, and the occurrence of seemingly productive communication.

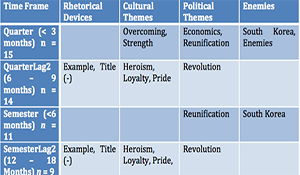

A war of words, such as that between China and the US, often contains clues to future actions that adversaries may take. NSI’s approach to discourse analysis is designed to uncover these clues and provide advance indicators and warnings (I&W) of impending political actions. NSI’s approach to discourse analysis combines analysis of cultural context, coding of subtle themes and ways of using language of which speakers are often unaware, and quantitative analysis of discourse in order to mitigate the challenges of this field of study. The result is a culturally and contextually sensitive analysis of meaning that can capture I&W that an adversary is unaware he/she or they are revealing.

The South China Sea disputes have a long history. The protagonists frequently issue statements, and actions are a veritable fire hose of gray zone activities. This creates a large volume of data, permitting the statistical analysis of correlations between discursive I&W and the amount of gray zone activity occurring during any period of time. In this study, correlations between discursive I&W and the number of gray zone activities (Island building, aggressive nautical maneuvers, fly overs) over the next six months were monitored from 2002 to 2016.

The question remains: in the escalated war of words, what might we expect for the future? This document seeks to answer this question by offering a prediction based on current events and prior NSI discourse work of what we can anticipate in this time of uncertainty.

The Trajectory of U.S./North Korean Nuclear War: Insights from Kim Jong Un’s Rhetoric.

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

Hours after the Washington Post broke the story that North Korea may have miniaturized a nuclear warhead, enabling its ICBM to deliver a nuclear blow to U.S. soil, President Trump announced that if North Korea continues to provoke, will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.” About two hours after that, North Korea responded that they were “carefully examining” plans for a missile strike on the U.S. Pacific territory of Guam. This was met by a boast from President Trump that the U.S. nuclear arsenal was more powerful than ever before. Senator John McCain, commenting on President Trump’s messages said, “That kind of rhetoric, I’m not sure it helps,” and described the situation as, “very, very, very “They serious.” Is this escalation of words catapulting the world to nuclear war?

Ongoing research highlights subtleties in Kim Jong Un’s use of language that indicate a distinct possibility that he could easily be provoked to a nuclear confrontation. However, this depends on an accurate assessment of the North Korean leader’s state of mind.

Indicators and warnings (I&W) in public speeches indicate national leaders’ intentions to test nuclear devices and missiles, and these I&W have been corroborated for Indian and Pakistani leaders as well as Kim Jong Un. Key indicators include expressions of pride, strength and overcoming. Understanding how these I&W are contextualized in a leader’s worldview is key to understanding what they might mean.

North Korea’s founder, Kim Il Sung, created a state religion, Juche, which frames North Koreans’ worldview and involves Korean nationalism, absolute obedience to and sacrifice for a strongman ruler, worship of the Kim family and an unending Manichean struggle against evil imperialists (West and Japan especially). Kim Jong Un relies extensively on Juche to frame all of his political messaging.

Kim Jong Un’s use of Juche religious themes nearly perfectly tracks his escalating nuclear weapons capability. In other world leaders, religious language has signaled openness to peace negotiations. The correlation of Kim Jong Un’s use of religious language and his testing seems contradictory, and potentially gives hope that he may be open to peace negotiations. However, worldview can radically change the meaning of these indicators.

Research on terrorist attempts to acquire and use weapons of mass destruction provides insight into how Kim Jong Un views this escalating situation. The key triggers that cause terrorists to pursue WMD are perceived need for extreme tactics, a mindset that favors simplistic solutions, and adherence to a religious ideology that stresses control, anger and identity politics. These characteristics appear to apply to Kim Jong Un entirely. Therefore, rhetoric and actions that reinforce his worldview are likely to cause him to escalate his own rhetoric and aggressive action. The consequences directly imperil the lives of 25 million South Koreans only 35 miles from the border, over a hundred million Japanese, and perhaps Americans in Guam or the lower 48.

NSI Submission to the Army University Press’s Mad Scientist Initiative: “Smoke, Mirrors and Mayhem: The Good Fight Remixed”.

Author | Editor: Macaulay, A. & Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc.).

The Army University Press created the Future Warfare Writing Program to generate ideas about possible complexities of future warfare, as presented in the U.S. Army Operating Concept. As part of this program, the Mad Scientist Initiative solicits short stories to help the US Army envision and anticipate changes in warfighting through creative means. Two of our NSI’ers, Ashton Macaulay and John Stevenson, submitted a short story to the competition. Although it was not selected as the winning submission, and at the risk of sounding biased, we think it’s a pretty good read! We hope that you will find it interesting and that it sparks your own ideas about the future of warfighting.

Below is the transcript of an interview with each of our writers, examining their creative process and how their background and training informed this work.

Q: Introduce yourself. Describe how you apply your academic background/technical training at NSI.

AM: I’m Ashton, a data scientist at NSI. My background is in experimental social psychology, and writing is how I spend most of my spare time. One of the first things that attracted me to NSI was the chance to tie psychological concepts to what can otherwise be the very quant heavy field of data science. NSI’s unique mix of professional backgrounds provides plenty of opportunities to harness our unique skillsets in ways that wouldn’t happen elsewhere.

JS: Hi, I’m John Stevenson, a Principal Research Scientist at NSI. Most of my work is with our public-sector clients. My training as a social scientist was primarily in political science and applied statistics. Much of my work focuses on how both non-state actors and governments organize violence to achieve key goals, such as regime durability, regime formation, border control, and economic extraction.

Q. What kind of fiction do you read/write, and does that connect to the way your academic background/technical training shapes your view of the world?

AM: I tend to stick to the sci-fi and adventure genres, with topics ranging from time-travel to monster hunting in the Andes. While I don’t call on social psychology explicitly in my writing, I do think it affects the way I write conflict and characters implicitly. Just understanding the fundamentals of group dynamics and what creates conflict in the world helps make shaping plot feel more natural.

JS: Almost all of the fiction I read now falls into the fantasy genre. I am currently working my way slowly through Stephen Erickon’s ten book series, “Malazan Tale of the Fallen.” Past fantasy loves have been Raymond E. Feist’s “Riftwar” and “Serpentwar” sagas, George R.R. Martin’s “A Song of Fire and Ice” series, and Octavia Butler’s “Kindred.” Before fantasy, my foundations were very solidly sci-fi. My beloved series are: Issac Asimov’s Foundation Series; Ray Bradbury’s “Martian Chronicles”; the Dune Series; Orson Scott Card’s Ender Wiggins Series, as well as the Ender’s Shadow Series.

The fiction I write tends toward more fantastical elements than sci-fi. Some of my recent projects have involved stories about a pantheon of gods building a shared universe together and the conflicts arising among these gods from distinct visions of cosmological organization. Another set of stories more explicitly draws on my political science training to craft a tales about the politics of secession and succession within a fantasy kingdom where key aspects of the current fantasy tropes are explicitly forsworn. For instance: the political geography is not claustrophobic from high density or rival polities, the biodome is extremely heterogeneous (and in some places untamed and dangerous), and kinship ties do not arise automatically from familial descent—heirs are chosen, and often are not the biological children of the nobility.

My academic training causes me to think a lot about violence as something that is manufactured (like a building) by specialists for state ends. Authors like Erickson also have helped me flesh out the agents of the state who are authorized to carry out violence as living, breathing persons themselves, who may or may not understand why they are manufacturing violence on behalf of the state.

Q. Ashton, we hear that you have a book of fiction coming out sometime soon? Can you tell us a bit more about that?

AM: I will be publishing my first novel through Abberant Literature in February of 2018! It’s a love letter to 80s big adventure cinema, following Nick Ventner, a drunken monster hunter who gets conned into going after a yeti deep in the Himalayas. The story is full of dark humor, and plenty of nods to Indiana Jones and my other favorite films. All I can say is I’m incredibly excited to get it out there, and for the hours of 5AM rewrites before work to stop :). For more details, you can check out my website, MacAshton.com, where I post updates, short fiction, and video game news.

Q. The Mad Scientist Initiative prompt concerned the future of warfighting that the DoD might face. What are the chief elements of the story, from your perspective, that addressed the futuristic element? What do you hope an analyst should pick up on and say to himself or herself, “Hey, we should be thinking about that?”

AM: I think the catalyst for this concept for me really centered around overpopulation and the recruitment of normal people into extremist groups, which is something we see already. That, coupled with the runaway advancements in technology means that we’ll have to adapt to a new brand of crime/criminal, which isn’t necessarily what we’d expect. Specifically, our connection to the web and the accessibility of information is only going to improve, and that’s going to open new doors, both good and bad.

JS: The story outlined four key predictions about futuristic war-fighting:

- The type of terrain: We wanted to highlight the challenges and opportunities of fighting in urban environments. While some of the challenges of mega-cities are known, thinking through the intelligence challenges of cities with slums in countries of limited capability/high corruption is something that planners and analysts ought to really consider. One example idea we floated were urban terrain maps created by satellites that partner/local governments provide to the United States as a part of intelligence-sharing/counter-terrorism efforts.

- The type of challenger: I am relatively convinced that wars between countries of equal fighting capability are a thing of the past. There is consensus that a war between peer nations—such as Britain and Russia, or even China and South Korea—is unlikely to happen. I also think that classic civil wars—both wars to control a capital city and name a new internationally recognized government and secessionist wars to create a new state with an internationally recognized government ruling in a new capital city—are also largely a thing of the past. Therefore, challengers to existing political order will come from non-state actors that are not seeking territorial rule but use violence, in part, to operate beneath or in opposition to the licit, legal organizations of civil society. Some of these organizations will be what we call terrorist groups (e.g., Niger Delta militants that destroy oil pipelines built by multi-national companies in Nigeria that they think harm the local environment), actors that we have labeled insurgents that do not appear to be pursuing political ends (e.g., the Lord’s Resistance Army in northern Uganda and South Sudan), new religious movements, and actors that are basically violent shipping companies (e.g., international narcotics and smuggling operators, Somali pirates, etc.).

- The type of soldier: A virtually-connected “smart” soldier for whom various devices connected to the ‘Internet of Things’ was our model. The idea was that over time soldiers would outsource a lot of basic tasks to machines that they controlled—like mapping terrain, identifying potential suspects, etc.—to allow them to spend more of their brain power on the appropriate uses of force to accomplish mission objectives. The type of devices previewed here on “our” side are: miniature small satellites/drones and advanced 3-D printers that help stabilize and repair wounds. The enemy side used chips containing biometric information and technology designed to impair other advanced technology.

- Blue team dynamics: Many of the war-games and scenario management situations limit how much they explore the interactions of various agencies on the same side (the blue team) that have statutory limitations on how they can coordinate and get involved, but may also face pressures from the Executive Branch to work together. We explicitly included in our future scenario some potentially illegal, and definitively rule-bending attempts to coordinate that were made at OLIE (Office of Low Intensity Engagements). The last piece of blue team dynamics was the slow mission creep such that the apprehension of an operative—who may or may not have actually been the person they were looking for—is counted as a win because they’ve at least learned more about one of the rival gangs.

Q. What are some elements of your own signature style that you included in the piece for more aesthetic reasons?

AM: No matter what I do, I like to include a bit of humor in it. In all my writing, there’s usually something that scares me, and a way of conquering that fear is to make light of it. Humor for me is a tool to look at a dark situation, understand it, but at the same time not be dragged down by it. I also think it helps keep people engaged, because after all, most of us are reading fiction for pleasure.

JS: Running inside jokes between characters—namely references to Batman—and tensions between colleagues working together are pieces of my signature style of writing that I made sure to work in there.

Q. In some ways, every story is a parable. Beyond the policy implications of the story, what are some aspects of the story that you hope provoke the reader to greater thought?

AM: Again, I think the details that talk about overpopulation are something we should all be thinking of, because in some places it is a reality, and in others, this problem is on its way. The buildings being cramped together so tightly that you can barely see the sky has been realized in big cities around the world. It’s only a matter of time before some of the more ‘out there’ aspects of our story become true.

JS: The story contained references to larger political winds that shaped the operations—namely an intelligence community that limited its accountability to Executive Branch (justified in our story by fear of Russian infiltration of the government) and an AUMF that was being used to provide legal cover for the use of American armed forces abroad—that should be potentially quite concerning to American citizens. Important questions to consider in this vein are:

- How independent ought the intelligence branches be from Executive control, even if the Executive is a Manchurian candidate?

- Why was there an operation going on in this random country anyway? What US interests were implicated by a smuggling organization—basically an illegal FedEx-Amazon hybrid—operating far away from the United States’ borders?

- What should be the United States’ interest and ability to get involved in low-intensity conflicts?

There are positive notes to the story as well. Where possible, gender-neutral names were used so as not to automatically invoke specific male or female traits into character interaction. In other situations, I specifically pushed for gendered names to show working environments with gender parity, which is not often the case in the policy side of the community. It may be a helpful exercise to note, when you first encounter a name, what you believe is the associated gender, and whether the pronouns, when used to refer to the character, correspond to what you thought.

AM: I’d want to make it longer and flesh out the characters a bit more. We were working under a strict word limit, which truncated the plot more than I would like. I think there’s an interesting overall narrative that could be built out into something bigger with more time.

JS: I would have included more information from the character with a Master’s degree about the gang they were fighting. I would have done so to really focus on how the knowledge of the organization’s ideological practices helped or hindered the operation. Secondly, I would have added more information about the organization’s ideological practices of invoking deities with operations.

Thank you for your time! We hope that our readers enjoyed learning from your answers as much as we did!

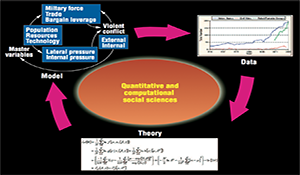

Utilizing Social Science Technology to Understand and Counter the 21st Century Strategic Threat

Author: Popp, R.

During the Cold War era, the strategic threat against the US was clear. The country responded clearly with a policy toward the Soviet threat that centered on deterrence, containment, and mutually assured destruction. To enforce this policy, the US created a strategic triad composed of nuclear intercontinental ballistic missiles, Trident nuclear submarines, and long-range strategic bombers. Today, however, our security environment is profoundly different. The strategic threat is far more complicated and dynamic. New and deadly challenges—from irregular adversaries to catastrophic weapons to rogue states—have emerged. The 21st-century strategic threat triad, made up of failed states, global terrorism, and WMD proliferation, represents the greatest modern-day strategic threat to our national security interests. With this new strategic triad’s emergence comes the need to craft a new agenda of military and national security priorities. Winning the war against these new threats will require more than victory on the battlefield. Recently, the US government published a revised national security strategy. It charters our military to reassure our allies and friends, to dissuade future military competition from would-be aggressors, to deter threats against US interests, and to decisively defeat any adversary if preemption and deterrence fail. To execute the new strategy, it’s vital that our military seek to deeply understand these new strategic threats. It’s not sufficient to predict where we might fight next and how a future conflict might unfold. We can no longer simply prepare for wars we would prefer not to fight; we must now prepare for those we will need to fight. Our new strategy requires that we make every effort to prevent hostilities and disagreements from developing into full-scale armed confrontations. This, in turn, requires applying political, military, diplomatic, economic, and numerous other social options to gain the necessary understanding of potential adversaries’ cultures and motivations. Indeed, we must be able to shape entire societies’ attitudes and opinions, with predictable outcomes.

Popp, R., “Utilizing Social Science Technology to Understand and Counter the 21st Century Strategic Threat,” IEEE Intelligent Systems, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 77-79, Sept/Oct, 2005.

Dominance in a Warfighting Domain Won’t Get Us There: Thoughts on a Comprehensive Approach for Space Security.

Author | Editor: A. Astorino-Courtois (NSI, Inc,).

Overview

Recent statements by senior national security space leaders dubbing space a “warfighting domain” and calling for US space superiority are not a sufficient foundation for achieving a stable security environment in space. In fact, as it appears now, the evolving US approach to space represents a textbook plan for escalating an arms race in space. A more comprehensive, three-part deterrence framework for space is suggested.

Over the next several decades, the US is likely to face a continuously evolving set of security challenges involving space. The good news is that US military superiority in the physical and digital domains seems to have raised the perceived cost of serious, direct military conflict with the US for Russia, China, and Iran among others. The not-so-good news is that US military dominance does not appear to have changed the security interests that lead to conflict with the US, but instead has pushed actors to change tactics to avoid open warfare with the US while continuing to pursue security objectives by other means. It is in this context of conflict short of warfare—what some have called the “gray zone”2—that the national security establishment frequently finds itself. Space is a vast yet crowded domain where operational challenges are exacerbated by the increasing prevalence of dual-use commercial-military technologies, and the difficulty of maintaining reliable situational awareness. It is perhaps the ultimate gray zone.

In response to the increase in space-based and counterspace activities among potential US adversaries, senior national security space (NSS) leaders have embarked on a public campaign of statements, interviews, conferences, and per newly customary political communications—Tweets, to signal a shift in the way that the US looks at space security. What was previously regarded as a sparsely-populated domain in which the US enjoyed overwhelming superiority, has in the past year or so been described as a crowded, contested “warfighting domain.” Air Force Secretary, Heather Wilson, and senior Air Force leaders recently made this point to Congress, arguing that—as in the air domain—the strategic imperative in space is to achieve superiority and dominance by defensive means or, if necessary, by attack.

The suggestion is that the US concept of the threat environment in space is continuing to evolve from one requiring that critical space systems have adequate defenses and that space services are resilient to interruption, to one that includes use of preemptive and kinetic action against adversary space capabilities that threaten our own. In other words, constructs such as deterrence and warfighting that are engrained in US strategic thinking about other domains, should be considered just as essential for space. If this is the case, the question becomes: Does identifying space as a “warfighting domain” and working/spending toward US space superiority constitute a sufficient foundation for sustainable and security in space?

ISIS and Religion and Nation Building in the Middle East.

Speaker: Landis, J. (University of Oklahoma’s College of International Studies).

Date: January 2017.

Joshua Landis is Director of the Center for Middle East Studies and Professor at the University of Oklahoma’s College of International Studies. He writes and manages “SyriaComment.com,” a daily newsletter on Syrian politics that attracts some 100,000 page-reads a month.

Dr. Landis publishes frequently in policy journals such as Foreign Policy and Foreign Affairs and speaks regularly at Washington think tanks. He is a frequent analyst on TV, radio, and in print. He has appeared recently on the PBS News Hour, the Charlie Rose Show, and Front Line. He is a regular on NPR and the BBC. He has received three Fulbright and other grants to support his research and won numerous prizes for his teaching. He is past President of the Syrian Studies Association.

He has lived 15 years in the Middle East and 4 in Syria. He spent most summers in Syria before the uprising on 2011. He was educated at Swarthmore (BA), Harvard (MA), and Princeton (PhD).

He is married to Manar Kashour and has two sons, Jonah and Kendall.