NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

Author | Editor: Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The Defining The Gray Zone video discusses how the gray zone is a conceptual space between peace and war, where activities are typically ambiguous or cloud attribution and exceed the threshold of ordinary competition, yet intentionally fall below the level of large-scale direct military conflict. This video highlights work that NSI did in collaboration with the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) office and the US Department of Defense to 1) define the gray zone and 2) validate the gray zone definition using NSI’s Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) methodology. For access to the full ViTTa analysis on the characterization and conditions of the gray zone, please visit: ViTTa Assessment and Analysis of the Gray Zone.

Violating normal: How international norms transgressions magnify gray zone challenges.

Author | Editor: Stevenson, J., Bragg, B., & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc).

The current international system presents multiple potential challenges to US interests. In recent years, state actors, especially but not limited to Russia and China, have taken actions that disrupt regional stability and potentially threaten US interests (Bragg, 2016). Many of these challenges are neither “traditional” military actions nor “normal” competition, but rather fall into a class of actions we have come to call “gray” (Votel, 2015). Here we define the concept as: “the purposeful use of single or multiple instruments of power to achieve security objectives by way of activities that are typically ambiguous or cloud attribution, and exceed the threshold of ordinary competition, yet intentionally fall below the level of [proportional response and] large-scale direct military conflict, and threaten the interests of other actors by challenging, undermining, or violating international customs, norms, or laws.” (Popp and Canna, 2016).

Many analyses have focused on the material effects of gray zone actions and gray strategies, such as changes to international borders, or threats to domestic political stability, however few have emphasized the role that international norms play in gray actions and gray strategies, and potential response to them. This paper beings to fill that gap by exploring the normative dimensions of gray zone challenges.

Specifying and systematizing how we think about the Gray Zone.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., Polansky (Pagano), S., & Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc).

In their continued work on the changing nature of the threat environment General Votel et al (2016) forecast that the majority of threats to US security interests in coming years will be found in a “gray zone” between acceptable competition and open warfare. They define the gray zone as “characterized by intense political, economic, informational, and military competition more fervent in nature than normal steady-state diplomacy, yet short of conventional war,” (pp. 101). While this characterization is a useful guide, it is general enough that efforts by planners, scholars and analysts to add the level of specificity needed for their tasks can generated considerable variation in how the term is applied, and to which types of actions and settings it applies.

What lies between acceptable competition and conventional war?

Far from an unnecessarily academic or irrelevant question, this is a critical question. How we define a condition or action, in other words the frame through which we are categorizing certain actions as threatening rather than “normal steady-state” impacts what we choose to do about them. The “I know it when I see it” case-by-case determination of gray vs not gray limits identification of gray zone actions to those that have already occurred. Gaining some clarity on the nature of a gray zone challenges is essential for effective security coordination and planning, development of indicators and warning measures, assessments of necessary capabilities and authorities and development of effective deterrent strategies.

The ambiguous nature of the gray zone and the complex and fluid international environment of which it is a part, make it unlikely that there will be unanimous agreement about its definition. Our first goal in this paper then, is to describe the gray zone as much as define it. We begin with a review the work of a number of authors who have written on the nature and characteristics of gray zone challenges, and use these to identify areas of consensus regarding the characteristics of the gray space between steady-state competition and open warfare. We next use these to suggest a more systematic process for characterizing different shades of gray zone challenges.

Quantifying Gray Zone Conflict: (De-)escalatory Trends in Gray Zone Conflicts in Colombia, Libya and Ukraine.

Author | Editor: Koven, B., Piplani, V., Sin, S. & Boyd, M. (START).

This report employs frequentist statistical analysis in order to model the effects of various factors, including the type of actors (state, violent non-state actor (VNSA) or civilian) involved and the prevalence of kinetic activity, on (de-)escalatory trends in Gray Zone conflicts. This is coupled with the development of a Bayesian Belief Network for predictive analysis of White, Gray and Black Zone behavior within Gray Zone conflicts.

Both sets of analyses utilize a version of the event-level data from the Worldwide Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS). However, we heavily modified this data prior to running the analyses. Specifically, we recoded new variables of particular interest to the study of Gray Zone conflict, addressed erroneous and duplicate entries, and restructured the data in order to model temporal changes. This was accomplished using a hybrid process involving both automated recoding procedures and expert human coders.

Our procedure was applied to three diverse gray zone conflicts: Colombia (01 January 2002 to 19 September 2016), Libya1 (01 January 2011 to 12 September 2016) and Ukraine (01 January 2014 to 12 September 2016). These conflicts all share two commonalities: they all entail a large amount of Gray Zone activity and myriad VNSAs. Nevertheless, the three cases vary in a number of important respects: the level of foreign involvement, the belligerents’ motives, as well as their guiding ideologies, and their geographic location. Consequently, the results are highly likely to be generalizable to a diverse array of other Gray Zone conflicts.

Three principal findings hold across both methodological approaches and are apparent in multiple cases. First, contrary to popular belief, kinetic military operations are a key aspect of Gray Zone conflicts. While it is true that these events are relatively sparse (around 20% of all events depending on the case), they have substantial influence in shaping non-kinetic events. Second, while VNSAs are less proficient than states at identifying their adversaries (de-)escalation trends, the closer VNSAs are linked to states, the less that this is a problem. Finally, legitimacy matters. For this reason, both VNSA and state forces will moderate their behavior in order to avoid being perceived as the aggressor or engaging in more (easily visible) civilian victimization than their opponents.

Question: What internal factors would influence Iran’s decision to interfere with the free flow of commerce in the Strait of Hormuz or the Bab el Mandeb?

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc).

Iran’s Strategic Interests

All of the SMEs either directly or indirectly referenced Iran’s strategic interests, and how these are informed by its overarching goal of regional hegemony. Dr. Belinda Bragg and Dr. Sabrina Pagano from NSI characterize these interests into three categories; prestige, economic; and security, all of which are moderated by domestic political constraints and pressures. Iran’s prestige interests center around ensuring that it does not lose face in its interactions with the US, and can increase its regional influence. Its economic interests focus on increasing Iran’s economic influence and security. Iran’s security interests include reducing threats from the US, Israel, and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, reducing the threat from ISIL, and broadcasting strength and challenging US influence and position in the region. Its domestic constraints and pressures include resisting cultural infiltration from the west, delivering economic improvement, and broadcasting strength. Together, these interests, and Iran’s overarching regional hegemony goal (Guzansky; Bragg & Pagano), ultimately shape the strategies that Iran pursues, including its decisions regarding the Strait of Hormuz or the Bab el Mandeb.

Iranian naval capabilities and desire for regional hegemony

Dr. Yoel Guzansky, of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, discusses how Iranian strategic thinking on the sea is no longer limited to the Persian Gulf, but instead extends to intended naval bases in Syria and Yemen, as well as influence in the Red Sea or even the Atlantic—ultimately “making every effort to demonstrate that its naval power is not limited to the Gulf alone.” Guzansky further indicates that these are more than just aspirational statements; the Iranian Navy has already extended its reach to the Red Sea and Bab el Mandeb, as well as Pakistan, China, and South Africa. These developments are consistent with Bragg and Pagano’s assessment that developing and demonstrating military capability is a key security strategy for Iran, as well as being seen, by hardliners and conservatives in particular, as an integral part of their regional hegemony goal. Guzansky draws a similar conclusion, adding that greater naval power will also increase Iran’s ability to help its regional allies. However, he also notes that “[t]o do so, Iran will need vast resources it doesn’t yet have.”

Guzansky indicates that, historically, Iran has prioritized the development of asymmetric capabilities (including anti-ship missiles, mines, and small vessel swarms), to enable it to better confront the U.S. Navy in the Gulf. Iran can leverage these same capabilities, and others, to interfere with the flow of commerce in the Strait of Hormuz, and to a lesser extent, the Bab el Mandeb.

Internal factors influencing Iranian interference in the Strait or Bab el Mandeb

The contributors identified the following internal factors as potentially influencing Iranian actions in the Strait of Hormuz or Bab el Mandeb:

Iran’s revolutionary doctrine

- Frames Iran as involved in an existential fight against US imperialism

- Makes it critical for Iran’s leaders, particularly conservatives and hardliners, to demonstrate to the Iranian people that they will not be bullied by the US

- Supports and informs Iran’s goal of regional hegemony Domestic political competition

- The role of factions—conservative / hardliner; moderate/pragmatist—in the prioritization of Iranian interests and the preferred strategies for achieving these interests

- With an election coming up in May, conservatives have incentive to switch the domestic political focus from cooperation with the US toward confrontation, to both appease their base and put greater pressure on Rouhani

Economic conditions

- Slow pace of improvement following JCPOA leaves moderates such as Rouhani politically vulnerable, and creates the belief that their promised benefits of greater openness and cooperation were unrealistic

- As the salience of economic concerns wanes relative to prestige and security concerns for the Iranian public, there is a greater likelihood that leaders (both conservative and moderate) will employ more bellicose rhetoric with regard to the Strait of Hormuz

- Closing the Straits will have significant short-term negative economic consequences for Iran, and depending on international and US response, may have longer-term consequences for Iran such as the re-imposition of sanctions and loss of trade and foreign investment

- Given Iran’s current economic situation and growing dependence on oil exports, it is unlikely to take action to close the Strait or Bab el Mandeb, as doing so would harm their economic interest further and thus be self-defeating

Popular perception that the US is not living up to terms of JCPOA

- Plays into hardline and conservative narratives emphasizing Western (especially US) hostility and untrustworthiness, giving credence to their own economic strategy, which seeks to limit openness to the West

- Increases the likelihood that the balance between the economic costs of interfering with commerce in either the Strait of Hormuz or the Bab el Mandeb, and the perceived benefit of demonstrating Iranian power and status, may swing in favor of the latter

External factors influencing Iranian interference in the Strait or Bab el Mandeb

The contributors argue that external factors also play a role in Iran’s decision-making with respect to its activities at sea.

Competition with Saudi Arabia

- Saudi Arabia’s opening of naval bases in Djibouti and Eritrea affords it an advantage in the Red Sea area

- Iran may wish to do “more to limit the Saudis by pushing harder on the question of access/use of both straits” (Vatanka)

- Retaliation for Saudi’s restricting Iranian access to the SUMED pipeline and selectively blocking Iranian ships in the Bab el Mandeb, which has stifled Iran’s establishment of trade with Europe

- Iran has potential to weaken Saudi government domestically by disrupting oil revenues and thus creating the conditions for greater internal unrest and instability

- Iran’s support of the Houthis, including provision of supplies to which the Houthis already have access, may actually serve to signal to and threaten Saudi Arabia and demonstrate Iran’s reach

Use of proxies

- The “effective blockade on Yemen,” which Iran’s current naval capabilities cannot challenge, creates a barrier to Iran helping the Houthis

- The Houthis may not be particularly dependent on Iran, given that they already have many of the supplies it provides, and Iran is unlikely to provide additional forms of support

- Ultimately, “I don’t think the Houthis want their tail in the trap of the Iran-Saudi conflict anyways” (Ehteshami)

- Yemen imports 90% of its food, much of this using foreign shipping. Further reduction in security in the Bab el Mandeb would threaten this supply, and therefore is not in the interests of the Houthis.

US actions and rhetoric

- Reinforce the perception that the US acted dishonestly with regard to JCPOA, seeking to thwart Iran’s efforts to increase trade and foreign investment

- Given the current domestic political climate, both conservatives and hardliners, as well as moderates, have greater incentive to frame any US action relative to Iran as threatening and conflictual, rather than cooperative

Iran’s strategic calculus with respect to interference in the Strait of Hormuz

Alex Vatanka, an Iran scholar from the Middle East Institute, and Bragg and Pagano of NSI indicate that closing the Strait may in fact work against Iran’s own interests, since it is as dependent on oil moving through the Strait as are its rivals. In this way, Iran may gain more value from threatening to close the Strait, which may increase oil prices, than from actually closing the Strait, which is sure to result in retributive actions, most likely from the US. As Vatanka indicates, a continued US presence in the Strait all but guarantees that Iran will use this strategic lever sparingly, if at all. Both Guzansky and Pagano and Bragg suggest that factors enhancing Iran’s likelihood of plausible deniability (use of asymmetric methods or proxies), by reducing the expected costs of such action, may, if other interests are met, instead increase the likelihood that Iran will choose to interfere.

Iran’s strategic calculus with respect to interference in the Bab el Mandeb

The strategic calculus for Bab el Mandeb may be different, as Bragg and Pagano note. There are two issues to consider with respect to potential Iranian interference in the Bab el Mandeb. These relate to both its capability to interfere and its motivation to do so. At present, Iran’s degree of control over the Houthis is unclear, and thus its ability to exact precise control over their activities may be limited. However, if Iran’s continued support of the Houthis gains them greater influence, then we can expect that the present Houthi control over Yemen’s ports might translate into greater Iranian interference in the Bab el Mandeb, assuming appropriate motivation.

This is where the Iranian calculus for the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab el Mandeb may come to differ. If Iran continues to pivot its trade toward greater interaction with China, India, and Southeast Asia, it will become less dependent on commerce in the Bab el Mandeb. Ehteshami also indirectly provides some support for this conclusion, indicating that the Bab el Mandeb represents more of a security rather than economic interest to Iran. As Bragg and Pagano indicate, this trade pivot means that the Bab el Mandeb becomes less strategically important to Iran as a source of economic power, but more strategically useful to Iran as a source of economic and other manipulation of its perceived rivals, such as Saudi Arabia. Moreover, this is accomplished while making Iran less vulnerable to economic and other manipulation from its rivals through selective blocking of its own ships’ passage. Iran does not have the same alternatives in the Strait of Hormuz, and cannot decrease its dependence on an open Strait for sea transportation, critical to its economic well-being. In these ways, the strategic calculus in favor of Iranian interference in the Bab el Mandeb, but not the Strait of Hormuz, may come to evolve over time in favor of increasing interference or escalation. For the time being, however, as Guzansky notes, this may be a more distant reality, given some of the present limits of Iran’s naval force, including the effective blockade on Yemen that prevents Iran from accessing Yemen’s shores.

Despite these challenges, Iran’s focus on achieving and maintaining regional hegemony, and its naval and other actions toward this goal, should not be ignored. Iran is increasingly likely to pursue strategies such as new trade partnerships that minimize the harm that its rivals can inflict, as well as those that enable it to increasingly project power, whether through the use of proxies of otherwise. As Guzansky notes, “unless improved Iranian naval capabilities receive a proper response, Iran in the future will be able to threaten crucial shipping lanes, impose naval blockades, and land special forces on distant shores should it deem it necessary.”

Contributing Authors

Bragg, B. (NSI), Ehteshami, A. (Durham University), Guzansky, Y. (Hoover Institution, Stanford University, & Tel Aviv University); Pagano, S. (NSI); Vatanka, A. (Middle East Institute & Jamestown Foundation)

Question (LR1): What opportunities are there for USCENTCOM to shape a post-ISIL Iraq and regional security environment promoting greater stability?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

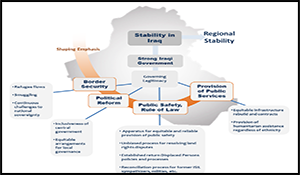

The expert contributors to this paper agree on the relationship between regional security and stability in Iraq: A strong and stable Iraqi government is a fundamental component of regional stability. The key to stability in Iraq is the popular legitimacy of central and local governance. Rather than operationally specific proposals, the experts suggest shaping objectives that USCENTOCM can use to prioritize and guide planning of shaping and engagement activities in four areas most critical for enhancing stability in Iraq: Political Reform Border Security, Public Safety, and Provision of Public Services. While USCENTCOM may take the lead in assisting Iraqis with issues such as border security and public safety, it likely would play a supporting role on the political and rule of law issues discussed below.

There is (uncharacteristic) agreement among international relations scholars on the factors that determine the stability of a state: 1) the extent to which it is seen as a legitimate governing authority by its population; 2) the degree to which the state has a monopoly on the use of force within its borders (i.e., internal sovereignty); and 3) the state’s ability to secure those borders (a component of external sovereignty).

Dr.’s Belinda Bragg and Sabrina Pagano of NSI use causal loops to illustrate the stability dynamics in Iraq and why it is impossible to ameliorate security concerns without also addressing the political and social factors that determine how people view the government. They write that in Iraq, “security is intrinsically linked to perceptions of governing legitimacy and the dynamics of ethno sectarian relations.” As a consequence, political reform that forges reconciliation between Shi’a and Sunni, and accommodates Kurdish and Arab desires for greater autonomy is an unavoidable prerequisite for a stable and legitimate Iraqi state. Similarly, Dr. Dianne Maye (Embry Riddle Aeronautical University) argues that encouraging local autonomy, decentralizing power out of Baghdad and structuring the government to avoid “concentration of power in any one ethnic, political, or religious group” are prerequisites for stability in Iraq. She recommends that the USCENTCOM should support work to shape the political environment in ways that promote “strong, yet dispersed, self-governance in a federal system” in Iraq that balances central government decision-making with the desire for increased autonomy in the provinces.

Security forces and police are often the most visible reflections of the domestic intentions and capability of the state. This is especially the case in a highly volatile security environment. In Iraq it is likely that a potent, locally appropriate but nationally coordinated security apparatus will be essential for implementing and assuring stability enhancing political reforms. USCENTCOM activities that encourage the capacity and help develop popular trust in the state’s security forces regardless of ethnic or sectarian divisions will be very important. The goal should be to shape Iraqi security activities to demonstrate the professionalism, impartiality and capacity of the security apparatus. The raison d’ etre of a government is to provide service to its citizens. When it is unable or unwilling to do so, it loses the trust of its constituents. Whenever possible and whenever it can be done fairly and impartially, the Government of Iraq, rather than sectarian security forces, Coalition forces, even NGOs should provide citizens with services such as public safety and policing, justice and reconciliation, humanitarian assistance and border control. This not only improves internal security and public safety but enhances the legitimacy of the government as well. While allowing non-NGO entities to provide local services may be expedient it is erode trust in the government and thus its longer-term ability to govern. When security forces are not seen as impartial and dependable protectors of all segments of society, more credible alternative sources of security will be found. This is precisely the context that facilitated ISIL’s rapid rise in Iraq.

Bragg and Pagano (NSI) recommend two ways in which USCENTCOM might help shape the situation. First, they suggest that USCENTCOM encourage consolidation of Iraqi security forces. This does not necessarily mean forging a single, central government tightly controlled national security organization, but that there is a single authority that sets the standards for national and regionally appropriate security forces. Second, encouraging recruitment of experienced Sunni officers – many of whom will be former Ba’athists – into the highest ranks of the Iraqi Security Forces and local police may help “alleviate fears that the process of removing ISIL forces will be used as cover for reprisals against Sunni populations … and as a means of bolstering Shia political and military dominance.” Failure to incorporate Sunni in leadership roles “increases the probability that Sunni tribal elders will look to provide their own security in the future” which will expand the number of sectarian militia and the number of security forces laying claims to authority.

Finally, John Collison of USSOCOM offers suggestions for promoting security prior to , and following the liberation of Mosul from ISIL. These efforts not only would help stabilize the volatile environment around Mosul but could serve as a template or set of precedents for post battle shaping in other areas of Iraq. In coordination with USG and Coalition partners USCENTCOM can engage with key military and militia leaders to help manage post liberation expectations and quell jockeying for political position, resources and territory among the groups operating in and around Mosul. Collison (USSOCOM) highlights two issues that demand particular and immediate attention: 1) the need to establish common understanding of the policies and procedures that will be used to return displaced persons to their homes in areas on able and equitable manner; and 2) articulation of reconciliation policies and procedures that will be used for those accused as ISIL sympathizers or having committed sectarian violence (e.g., screening process, arrest criteria, who would stand trial, etc.)

Contributing Authors

Bragg, B. (NSI), Pagano, S. (NSI), Gompert, D. (RAND), Collison, J. (USSOCOM), Maye, D. (Embry Riddle Aeronautical University)

Question (R3 QL3): What are the aims and objectives of the Shia Militia Groups following the effective military defeat of Da’esh?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

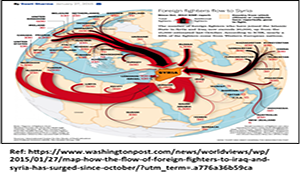

Referring to the Shi’a Militias as a unitary or homogenous entity masks the reality that what are now dozens of groups in Iraq were established at different times and for different reasons, and thus have different allegiances and goals. 1 Dr. Daniel Serwer of Johns Hopkins SAIS puts it succinctly, “Not all ‘Shi’a militia groups’ are created equal.” An actor’s defining characteristics have a significant impact on the objectives it pursues. The expert contributors highlight two factors we might use to differentiate the many Shi’a militia groups in Iraq, their aims, objectives and likely post-ISIS actions. These are: 1) the extent to which the group is led by and owes allegiance to Iran; and 2) the span of its concerns and interests. How groups rate on these two factors will tell us a lot about what we should expect of them following the effective defeat of ISIS (see graphic).

Autonomy. Contributors to this Quick Look tended to differ on where the balance of control over the Shi’a militias rests. Some see the Shi’a PMF groups as primarily under the control of Iran, and thus motivated or directed largely by Iranian interests (i.e., they have very little autonomy.) If this is the case, knowing the interests of the leaders of these groups will tell us little about their actions). Other experts view the militias as more autonomous and self- directed albeit with interests in common with Iran in which case their interests are relevant to understanding their objectives. In reality, there are groups that swear allegiance to the Supreme Leader in Iran, those that follow Ayatollah al Sistani, and still other groups that respond only to their commanders. In an interview with the SMA Reachback team, Dr. Anoush Ehteshami a well-known Iran scholar from Durham University (UK) points out that Iran has “shamelessly” worked with groups it controls as well as those that it does not because it sees each variety as a “node of influence” into Iraqi society. As in previous Reachback Quick Looks2, a number of the SMEs note that Iran is best served by taking a low- key approach in Iraq. Ehteshami argues that ultimately Iran has little interest in appearing to control the Shi’a militias: “the last thing that they want is to be seen as a frontline against Daesh” as this would reinforce the Sunni versus Shi’a sectarian, Saudi-Iranian rivalry undercurrents of the conflict against ISIS. In fact he argues that Iran prefers to work with the militias rather than the central government – which is susceptible to political pressure that Iran cannot control in order to “maintain grass root presence and influence … of the vast areas of Iraq which are now Shia dominated.”

Ambition. A second factor that distinguishes some militia groups is the span of their key objectives and ambition. In discussing militia objectives, some SMEs referenced groups with highly localized interests, for example groups that were established more recently and primarily for the purpose of protecting family or neighborhood. Others mentioned (generally pro-Iran) groups with cross-border ambitions. However, the major part of the discussion of militia objectives centered on more-established and powerful groups with national-level concerns.

Key Objectives

Most experts mentioned one or all of the following as key objectives of the Shi’a militia, at present and in post-ISIS Iraq. Importantly, many indicate that activities in pursuit of these objectives are occurring now – the militias have not waited for the military defeat of ISIS.

Controlling territory and resources

For groups with very localized concerns this objective may take the form of securing the bounds of an area, or access to water in order to protect family members or neighborhoods. For groups with broader ambitions, American University of Iraq Professor Christine van den Toorn argues that controlling territory and resources is a means to these militias’ larger political goals. As in the past, this may entail occupying or conducting ethnic cleansing of areas of economic, religious and political significance (e.g., Samarrah, Tel Afar, former Sunni areas of Salahuldeen Province near Balad.) Here too Anoush Ehteshami suggests that different militia groups have different allegiances and motives: some are “keen to come flying a Shia flag into Sunni heartlands and are determined to take control of those areas.” A number of authors indicate that a specific project of Iran-backed militias possibly with cross-border ambitions would be to secure Shi’a groups’ passage between Iraq and Syria (van den Toorn suspects this would be north or south of Sinjar adding that Kurds would prefer that the route “go to the south, through Baaj/ southern Sinjar and not through Rabiaa, which they want to claim.”)

Consolidating political power and influence

Anoush Ehteshami believes that the Shi’a militia groups are keen to gain as much “control of government as possible, as quickly as possible.” These groups are actually new to Iraqi politics and realize that once the war is over their influence and role in the political order may end. Many of the experts identified the primary objective of militia groups with broader local or national ambitions as increasing their independence from, and power relative to Iraqi state forces. Christine van den Toorn relates an interesting way that some Shi’a militias are working to expand their influence: by forging alliances with “good Sunnis” or “obedient Sunnis.” In fact, she reports that the deals now being made between some Sunni leaders and Shia militia/PMF are in essence “laying the foundation of warlordism” in Iraq and potentially cross-nationally. Many experts singled out the law legalizing the militias as making it “a shadow state force” or an Iraq version of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (RGC) – a clear victory for those seeking to institutionalize the political wealth, and likely economic wealth of the militias.

Dr. Harith Hasan al-Qarawee of Brandeis University agrees that the primary goal of the militia groups with national or cross-national ambitions is to gain political influence in Iraq in order to: “to improve their chances in the power equation and have a sustained access to state patronage.” As a result, he anticipates that they will continue to work to weaken the professional, non-sectarian elements of the Iraqi Security Forces, and would accept reintegration into the Iraqi military only if it affords them the same or greater opportunity to influence the Iraqi state than what they currently possess. Finally, a number of the experts including Dr. Randa Slim of the Middle East Institute, mention that an RGC-like, parallel security structure in Iraq will also serve Iran as a second “franchisee” along with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and allow export of “military skillsets/expertise/knowhow, which can be shared with fellow Shia groups in the Gulf region.”

Eliminating internal opposition from Sunni and Kurds

Omar Al-Shahery, a former deputy director in the Iraqi Defense Ministry, along with a number of other SME contributors believe that after the Sunni Arabs are “taken out of the equation” the Kurds are the militias’ “next target.” Dr. Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins SAIS) expects that Shi’a forces will remain in provinces that border Kurdistan, if not at the behest of Iran, then certainly in line with Iran’s interest in avoiding an expanded and independent Kurdistan in Iraq. Al Shahery (Carnegie Mellon) points to this as the impetus for militias pushing the Peshmerga out of Tuzkurmato south of Kirkuk. Similarly, Shi’a concern with Saudi support reaching Sunni groups opposed to the expansion of Shi’a influence in Iraq was motivation for occupying Nukhaib (south Anbar) and cutting Sunni forces off from a conduit to aid. Finally, Al-Shahery raises the possibility that the ultimate goal of the most ambitious militia groups is in fact to form an “integrated strike force” that can operate cross-nationally. This is evidenced he argues, by the centralization of the command structure of the forces operating in Syria.

What to Expect after Mosul

The following are some of the experts’ expectations about what to expect from the Shi’a militias in the short to mid-term. See the author’s complete submission in SME input for justification and reasoning.

- Re-positioning. Iran will encourage some militia forces to relocate to Syria to help defend the regime. However, Iran also will make sure that the “Shia militias which have been mobilized, are going to stay mobilized” as a “pillar of Iran’s own influence in Iraq” (Dr. Anoush Ehteshami, Durham University, UK)

Following ISIS defeat in Iraq …

- Inter and intra- sectarian conflict. The PMFs will play a “very destabilizing” role in Iraq if not disbanded or successfully integrated into a non-sectarian force. The present set-up will result in renewed Sunni-Shia tensions, Sunni extremism (Dr. Monqith Dagher, IIACSS and Dr. Karl Kaltenthaler, University of Akron); Shi’a-Shi’a violence (Dr. Sarhang Hamasaeed, USIP); and/or violent conflict with the Kurds (Dr. Daniel Serwer, Johns Hopkins SAIS; Omar Al-Shahery, Carnegie Mellon)

- New political actors. Select militia commanders will leave the PMF to run for political office, accept ministerial posts (Dr. Daniel Serwer, Johns Hopkins SAIS) and/or “major political players in Baghdad” will attempt to place them in important positions in the police or Iraqi security force positions. (Dr. Diane Maye, Embry-Riddle)

Contributing Authors

Ford, R. (Middle East Institute), Slim, R. (Middle East Institute), Abouaoun, E. (US Institute of Peace); al-Qarawee, H. (Brandeis University), Al-Shahery, O. (Carnegie Mellon University), Atran, S. (ARTIS), Dagher, M. (IIACSS), Gulmohamad, Z. (University of Sheffield), Ehteshami, A. (Durham University), Kaltenthaler, K. (University of Akron), Mansour, R. (Chatham House), Hamasaeed, S. (US Institute of Peace), Maye, D. (Embry Riddle University), Nader, A. (RAND), Serwer, D. (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies), van den Toorn, C. (American University of Iraq, Sulaimani), Wahab, B. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy)

Question (QL1): What are the factors that could potentially cause behavior changes in Pakistan and how can the US and coalition countries influence those factors?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

The experts who contributed to this Quick Look agree on an essential point: Pakistan’s beliefs regarding the threat posed by India are so well-entrenched that they not only serve as the foundation for Pakistan’s foreign policy and security behavior, but represent a substantial barrier to changing it behavior. Christine Fair a Pakistan scholar from Georgetown University is specific as to the target of any influence efforts – difficult as they may be: “the object of influence is not ‘Pakistan;’ rather the Pakistan army’ and so security behavior change if possible requires change in the Army’s cost-benefit calculus. The essential components of Pakistan’s security beliefs are first that India is an existential threat to the state; and second that Pakistan is at a tremendous military and economic disadvantage to its stronger neighbor. Tom Lynch of the National Defense University adds a third: Pakistan’s national self-identity as an ‘oppositional state, created to counter India.’ The nature of behavior change is relative and can occur in (at least) two directions: one aligning with the observer’s interests (for the sake of brevity referred to here as ‘positive change’), and one in conflict with those interests (‘negative change’). Encouraging positive change in Pakistani security behavior was seen by each of the experts as an extremely difficult challenge, and one that would likely require dramatic change in Pakistan’s current internal and external security conditions. The experts also generally agreed that negative change in Pakistani behavior is easily generated with no need for dramatic changes in circumstance.

Negative Change: Easy to Do

According to long-time Pakistan scholar and Atlantic Council Distinguished Fellow Shuja Nawaz, Pakistan’s current state is to “to view its regional interests and strategies at a variance from the views of the US and its coalition partners.” Moreover, Pakistan’s willingness to cooperate with US/Western regional objectives can deteriorate rapidly if the Pakistani security establishment believes those states have dismissed as invalid, or take actions that exacerbate their concerns. Specifically, actions that reinforce the perceived threat from India (e.g., Indian military build-up, interest in Afghanistan) or Pakistan’s inferior position relative to India (e.g., US strengthening military and economic ties with India; Indian economic growth) stimulate negative change. Importantly, because the starting point is already “negative” relative to US interests, these changes can take the form of incremental deterioration in relations, rather than obvious and dramatic shifts in behavior. Examples may include increased emphasis on components of Pakistan’s existing nuclear weapons program, amplified use of proxy forces already in Afghanistan, or improved economic relations with Russia.

Levers Encouraging Positive Change: A difficult Challenge

While the experts agreed that Pakistan’s deep-rooted, security-related anxieties inhibit changes in behavior toward greater alignment with coalition objectives; they clearly diverge on what, if anything might be done to encourage positive change. Two schools of thought emerged: what we might (cheekily) refer to as a “been there” perspective; and a longer- term, cumulative influence view.

“Been there” School of Thought

Tom Lynch (NDU) argues that the security perceptions of Pakistan’s critical military- intelligence leaders have been robustly resistant to both pol-mil and economic incentives for change2 as well as to more punitive measures (e.g., sanctions, embargos, international isolation) taken to influence Pakistan’s security choices over the course of six decades. Neither approach fundamentally altered security perceptions. Worse yet, punitive efforts not only failed to elicit positive change in Pakistan’s security framework but ended up reducing US influence by motivating Pakistan to strengthen relations with China, North Korea and Iran. As a consequence of past failure of both carrot and stick approaches, both Lynch and Christine Fair (Georgetown) argue that motivating change in Pakistani security behavior requires “a coercive campaign” to up the costs to Pakistan of its proxy militant strategy (e.g., in Afghanistan by striking proxy group leaders; targeted cross-border operations)3. Moreover, Lynch feels that positive behavior change ultimately requires a new leadership. Raising the costs would set “the conditions for the rise of a fundamentally new national leadership in Pakistan” and be the first step in inducing positive behavior change. Lynch believes these costs can be raised while at the same time US engagement continues with Pakistan – in a transactional way with Pakistan’s military-intelligence leadership and in a more open way through civilian engagement and connective projects with the people of Pakistan. However, Christine Fair points to US domestic challenges that mitigate against the success of even these efforts given what she argues is a lack of political will “in key parts of the US government which continue to nurse the fantasy that Pakistan may be more cooperative with the right mix of allurements.”

Cumulative Influence School of Thought

Other contributors however believe are not ready to abandon the possibility of incentivizing positive change in Pakistan’s foreign policy and security behavior. They argue that there are still actions that the US and coalition countries could take to reduce Pakistani security concerns and encourage positive change. Admittedly, the suggested measures are not as direct as those suggested by abeen there, done that approach and assume a significantly broader time horizon:

- Do not by-pass civilian authority. Equalize the balance of US exchanges with Pakistani military and civilian leaders rather than depending largely on military-to-military contact. Governing authority and legitimacy remain divided in Pakistan, and while dealing directly with the military may be expedient, analysis shows that by-passing civilian leadership and continuing to the treat the military as a political actor inhibits development of civilian governing legitimacy, strengthens the relative political weight of the military, and will in the longer term foster internal instability in Pakistan and stymie development of the civil security, political and economic institutions necessary for building a stronger, less threatened state.4 In this case the short-term quiet that the military can enforce, is off-set by increased instability down the road.

- Reduce the threat. A direct means of reducing the threat perceptions that drive Pakistani actions unfavorable to coalition interests is to actually alter the threat environment. One option suggested for doing this is to use US and ally influence in India to encourage that country to redirect some of the forces aimed at Pakistan. A second option is to develop a long-term Pakistan strategy (“not see it as a spin-off or subset of our Afghanistan or India strategies”) was seen as a way to signal the importance to the US of an enduring the US-Pakistan relationship.

- Remember that allies got game. Invite allies to use their own influence in Pakistan rather than taking the lead on pushing for change in Pakistan’s behavior. According to Shuja Nawaz, “…the Pakistanis listen on some issues more to the British and the Germans and Turks. The NATO office in Islamabad populated by the Turks has been one of the best-kept secrets in Pakistan!”

- Enlist Pakistan’s diplomatic assistance. Finally, Raffaello Pantucci of the Royal United Services Institute (UK) suggests enlisting Pakistan to serve as an important conduit in the dispute that could most rapidly ignite region-wide warfare: that between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Pakistan has sectarian-based ties with Saudi Arabia as well as significant commercial ties with Iran. Although as MAJ Shane Aguero points out increased Saudi-Iranian hostilities could put Pakistan in an awkward position, Pantucci believes that the US and allies could leverage these relations to open an additional line of communications between the rivals. Importantly, doing so would also important signal US recognition of Pakistan’s critical role in the region, which would enhance “Pakistani sense of prestige which may in turn produce benefits on broader US and allied concerns in the country.”

Contributing Authors

Nawaz, S. (Atlantic Council South Asia Center), Abbas, A. (National Defense University), Lynch, T. (Institute of National Strategic Studies – National Defense University),

Aguero, S. (US Army), Venturelli, S. (American University), Pantucci, R. (Royal United Services Institute), Fair, C. (Georgetown University)

Question (R3 QL4): What are the critical elements of a continued Coalition presence, following the effective military defeat of Da’esh [in Iraq] that Iran may view as beneficial?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Dr. Omar Al-Shahery of Carnegie Mellon University offers a critical caveat in considering the question posed for this Quick Look. While Iran may see certain “advantages” of the presence of Coalition forces, Iran’s perspective is both relative to the nature of the context and thus transitory as “such benefits might not necessarily outweigh the disadvantages from the Iranian point of view.” If our starting point is that Iran is not happy to have US/ Coalition military forces in the region, then what we are looking for are those Coalition activities that might be seen as minimally acceptable, or “less unacceptable”.

The expert contributors were somewhat divided on whether they believed there were any Coalition elements or activities that they thought Iran might find beneficial. Some believe that there are Coalition activities, primarily related to defeating ISIS, that Iran would find beneficial. Others however do not believe that there is any US military presence in Iraq that would be seen by Iran as sufficiently beneficial to counter the threat that that presence represents. Dr. Anoush Ehteshami, an Iran expert from Durham University, UK, argues that both sides are correct; the difference is whether we are looking at what the majority of experts agree is Iran’s preference, or at Iran’s (present) reality. In other words, it is the ideal versus the real.

However, simply recognizing the ideal versus the real is not sufficient to address the question posed. When the question is essentially what determines the limits of Iran’s tolerance for Coalition activities in Iraq. Context matters. This is because Iran’s perception of political and security threat perception is not based solely on the actions of the West/US, but is the result of (at least) three additional contextual factors: 1) the immediacy of the threat from ISIS or Sunni extremism; 2) the intensity of regional conflict, particularly with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s closest major rival; and, 3) as discussed in SMA Reachback LR2 three-way domestic political maneuvering between Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Rouhani government. This should not be discounted as a key factor in Iran’s tolerance for Coalition presence in the region. The Context can push the fulcrum point such that Coalition activities tolerable under one set of circumstances are not acceptable under others.

The contributors to SMA Reachback LR2 that should be expected to feature in almost any Iranian calculus in the near to mid-term. Relevant to this question these are: 1) expanding Iranian influence in Iraq, Syria, and the region to defeat threats from a pro-US Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Israel and the US; and 2) eliminating the existential threat to Iran and the region’s Shi’a from Sunni extremism.

Iran’s Concerns in Iraq

In general, the experts suggest that from its perspective, Iran’s ideal situation in Iraq would include the following: ISIS is defeated and Sunni extremism is otherwise under control. Iraq is stable and unified with political and security establishments within which Iran has significant, yet understated influence. The ISF are strong enough to maintain internal calm in Iraq, but too weak to pose a military threat to Iran. The strongest Shi’a militia elements are developing into a single Revolutionary Guard Corps type force that is stronger than the ISF. Finally, the major security threats from Israel and Saudi Arabia are minimal and there is no US military presence in Iraq and it is very limited in the rest of the region. This is the scenario that sets the Iranian reference point. All else is a deviation from this.

The Ideal

Iran needs the Coalition for one thing: security. This is security sufficient to defeat ISIS and to stabilize Iraq without posing a threat to Iranian influence. Of course, ISIS, and Sunni extremism more generally has not yet been defeated in Iraq. Iraq is not secure and the Coalition forces have a different perspective on the requirements for a viable Iraqi state (e.g., an inclusive government, a single, unified and non-sectarian security force). The Saudis are irritated, the US remains present in the region, and who knows what Israel is apt to do. According to Iran scholar Dr. Anoush Ehteshami (Durham University, UK), Iranian leaders recognize that they lack the capacity now to defeat ISIS and bring sufficient stability to Iraq to allow for reconstruction. As a result, Iran appears willing to suffer Coalition presence in order to gain ISIS defeat and neutralize Sunni extremism in Iraq – arguably Iran’s most immediate threat. As Dr. Daniel Serwer observes, “for Iran, the Coalition is a good thing so long as it keeps its focus on repressing Da’esh and preventing its resurgence.” Once ISIS is repressed and resurgence checked, the immediate threat recedes (i.e., the context changes) and Iran’s tolerance for Coalition presence and policies in Iraq will likely shift as other interests (e.g., regional influence) become more prominent. The critical question is where the fulcrum point rests, in other words, where is the tipping point at which Coalition presence in Iraq becomes intolerable enough to stimulate Iranian action.

In Reality

In a nutshell, Iran is most likely to find Coalition elements acceptable if they allow Iran to simultaneously 1) eliminate what is sees as an existential security threat from ISIS and Sunni extremism, and 2) expand its influence in Iraq and the region which is a the pillar of its national security approach. Any Coalition element that fails on one of these is unlikely to be tolerated. Put another way, Coalition elements that defeat ISIS but derail Iran’s influence in Iraq will not likely be seen as beneficial. Likewise, as multiple experts point out, Iran is aware that it cannot stabilize Iraq on its own regardless of how much influence it has there.

Contributing Authors

Al-Shahery, O. (Aktis & Carnegie Mellon University), Ford, R. (Middle East Institute); Hamasaeed, S. (US Institute of Peace), Mansour, R. (Chatham House), Maye, D. (Embry Riddle University), Nader, A. (RAND); van den Toorn, C. (American University of Iraq, Sulaimani), Wahab, B. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Meredith, S. (National Defense University), Vatanka, A. (Middle East Institute), Ehteshami, A. (Durham University), Serwer, D. (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies)

Drivers of Conflict and Convergence in Eurasia in the Next 5-25 Years — Integration Report.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc).

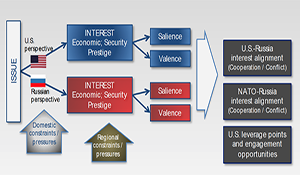

Evaluating strategic risk in the Eurasia region over the next two to three decades is a complex challenge that is vital for USEUCOM planning and mission success. The depth of our understanding of the diverse set of political, economic, and social actors in the region will determine how effectively we respond to emerging opportunities and threats to US interests. A better understanding of Russia’s priorities and interests, and their implications, both regionally and globally, will help planners and policy makers both anticipate and respond to future developments.

The official project request from USEUCOM asks that SMA “identify emerging Russian threats and opportunities in Eurasia (with particular emphasis on EUCOM AOR countries). The study should examine future political, security, societal and economic trends to identify where US interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests, and in particular, identify leverage points when dealing with Russia in a “global context” Additionally, the analysis should consider where North Atlantic Treaty Organization interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests” They also provided a list of questions covering: regional outlook; China; regional balance of power; Russian foreign policy; leadership; internal stability dynamics; media and public opinion; US foreign policy and regional engagement; NATO.

To address these questions, SMA brought together a multidisciplinary team drawn from the USG, think tanks, industry, and universities. The individual teams employed multiple methodological approaches, including strategic analytic simulation, qualitative analyses, and quantitative analyses, to examine these questions and the nature of the future operating environment more generally.

The diverse range of approaches and sources utilized by the individual teams working on the EUCOM project is one of the strengths of the SMA approach; however, it also makes comparison and synthesis across individual reports more challenging. For this reason, NSI developed a structured methodology for integrating and comparing individual project findings and recommendations in a systematic manner.

This report provides an overview of the regional issues identified by the US, Russia, NATO and EU in policy statements, speeches, and the media, and how they intersect with actor interests. It then presents the major themes arising from the integration of the team findings in response to USEUCOM’s question, in particular the importance of understanding Russia’s worldview, and the subsequent recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing the probability of cooperation with Russia.