NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

Drivers of Conflict and Convergence in Eurasia in the Next 5-25 Years — Integration Report: Executive Summary.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc).

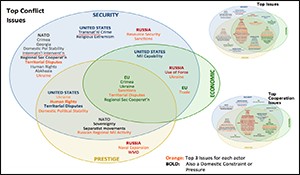

This project identified threats and opportunities in Eurasia (with particular emphasis on USEUCOM area of responsibility (AOR) countries). This report provides an overview of the regional issues identified by the US, Russia, NATO, and the EU in policy statements, speeches, and the media, and how they intersect with actor interests. It then presents the major themes arising from the integration of the team findings in response to USEUCOM’s questions, in particular the importance of understanding Russia’s worldview, and the subsequent recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing the probability of cooperation with Russia.

Evaluating strategic risk in the Eurasia region over the next two to three decades is a complex challenge that is vital for USEUCOM planning and mission success. The depth of our understanding of the diverse set of political, economic, and social actors in the region will determine how effectively we respond to emerging opportunities and threats to US interests. A better understanding of Russia’s priorities and interests, and their implications, both regionally and globally, will help planners and policy makers both anticipate and respond to future developments.

The official project request from the United States Navy asked that the Strategic Multi:Layer Assessment (SMA) team “identify threats and opportunities in Eurasia (with particular emphasis on USEUCOM area of responsibility (AOR) countries). The study should examine future political, security, societal, and economic trends to identify where US interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests and, in particular, identify leverage points when dealing with Russia in a ‘global context.’ Additionally, the analysis should consider where North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests.”

To address these questions, SMA brought together a multidisciplinary team drawn from the United States Government (USG), think tanks, industry, and universities. The individual teams employed multiple methodological approaches, including strategic analytic simulation, qualitative analyses, and quantitative analyses, to examine these questions and the nature of the future operating environment more generally.

The diverse range of approaches and sources utilized by the individual teams working on the USEUCOM project is one of the strengths of the SMA approach; however, it also makes comparison and synthesis across individual reports more challenging. For this reason, NSI developed a structured methodology for integrating and comparing individual project findings and recommendations in a systematic manner.

This report provides an overview of the regional issues identified by the US, Russia, NATO, and the EU in policy statements, speeches, and the media, and how they intersect with actor interests. It then presents the major themes arising from the integration of the team findings in response to USEUCOM’s questions, in particular the importance of understanding Russia’s worldview, and the subsequent recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing the probability of cooperation with Russia. The report is structured as follows:

- Identifying issues and mapping actor interests in the USEUCOM AOR

- Russia’s worldview

- Regional cooperation and conflict

- Domestic stability and instability in Russia

- Recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing cooperation

Question (V7): Objectives and Motivations of Indigenous State and Non-State Partners In the Counter-Isil Fight. What are the strategic objectives and motivations of indigenous state and non-state partners in the counter-ISIL fight?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

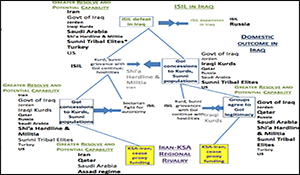

The following are high-level results of a study assessing Middle East regional dynamics based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolve. Expected outcomes are based on the strategic interests of regional actors.

ISIL will be defeated in Syria and Iraq

Based on the balance of actor interests, resolve and capability, the defeat of Islamic State organization seems highly likely (defeat of the ideology is another matter). Specifically, the push for ISIL defeat in Syria is led by Iran and the Assad regime, both of which have high potential capacity and high resolve relative to ISIL defeat. Only ISIL has high resolve toward ISIL expansion in Syria. Iran, Jordan,Iraqi Kurds, Saudi Arabia, and Shi’a Hardline & Militia, show highest resolve for ISIL defeat in Iraq.

Conflict will continue in Syria following ISIL defeat; will escalate significantly with threat of Assad defeat

Whether Syrian civil conflict will cease in the context of an ISIL defeat is too close to call. Assad, Russia and Iran have strong untapped capability to drive an Assad victory against the remaining Opposition although none show high resolve (i.e., the security value gained by an Assad victory versus continued fighting in Syria is not widely different. This reflects the Assad regime’s competing security interests (i.e., one interest is better satisfied by continued conflict, another by Assad victory). Even when we assume the defeat of ISIL in Syria as a precondition, unless actor interests change dramatically, the number of interests served by continued conflict and the generally low resolve on both sides suggests that we should be skeptical of current agreements regarding the Syrian Civil War. Moreover, resolve scores rise sharply when continued conflict is replaced by the possibility of Assad defeat. Together these results suggest that unless Assad’s, Iran’s and Russia’s perceived security concerns are altered significantly, these actors have both the capacity and will to engage strongly to avoid an impending defeat. The high resolve of the three actors to avoid defeat should be taken as a warning of their high tolerance for escalation in the civil conflict.

Implication: Tolerating Russian-Iranian military activities in Syria and redirecting US resources to humanitarian assistance of refugees in and around Syria has greater value across the range of US interests and aligns more fully with the balance of US security interests in the region.

GoI lacks resolve to make concessions to garner support from Sunni Tribes

While the majority of regional actors favor the Government of Iraq (GoI) making concessions to Sunni and Kurdish groups following defeat of ISIL, only the Government of Iraq, Shi’a Hardline and Militia, Sunni Tribes and Iraqi Kurds have significant capability to cause this to happen or not. Unfortunately, the GoI and Shi’a have high resolve to avoid reforms substantive enough to alter Sunni factions’ indifference between GoI and separate Sunni and/or Islamist governance. More unfortunately, when they believe the GoI will not make concessions, Sunni Tribes are indifferent between ISIL governance and the current Government controlling Iraq. That is, they have no current interest served by taking security risks associated with opposing ISIL. However, the outbreak of civil warfare in Iraq does incentivize GoI to make concessions. Iranian backing of substantial GoI reforms changes the GoI preference from minimum to substantive reforms without the necessity of civil warfare.

Implication: Now is the opportune time to engage all parties in publically visible dialogue regarding their views and requirements for post-ISIL governance and security. Engaging Sunni factions on security guarantees and requirements for political inclusion/power is most likely to be effective; Engaging Kurds on economic requirements and enhancing KRG international and domestic political influence encourage cooperation with GoI. Finally, incentivize Iran to help limit stridency of Shi’a hardline in Iraq eases the way for the Abadi government to make substantive overtures and open governance reform talks.

Saudi Arabia-Iran Proxy funding continues; easily reignites conflict

Use of proxy forces by Saudi Arabia and Iran is one of the quickest ways to reignite hostilities in the region, and even though direct confrontation between state forces is the worst outcome for both, the chances of miscalculation leading to unwanted escalation are very high. Both Saudi Arabia and Iran have high resolve to continue supporting regional proxies up to the point that proxy funding or interference prompts direct confrontation between state forces. This is driven by mutual threat perception and interest in regional influence. This leaves open the specter that any conflict resolution in the region could be reignited rapidly if the incentives and interests of the actors involved are not changed.

Implication: International efforts to recognize Iran as a partner, mitigate perceived threat from Saudi Arabia and Israel, and expand trade relations with Europe are potential levers for incentivizing Iran to limit support of proxies. Saudi Arabia may respond to warning of restrictions on US support if proxyism is not curtailed.

Contributing Authors

Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI), Berti, B. (Institute for National Security Studies, Tel Aviv; Fellow, Foreign Policy Research Institute), Bragg, B. (NSI), Brom, S. (Center for American Progress), Canna, S. (NSI), Gengler, J. (Qatar University), Hassan, H. (Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy), Hecker, M. (Institut Français des Relations Internationales), Khashan, H. (American University of Beirut), Kuznar, L. (NSI), Lynch, T. (National Defense University), Popp, G. (NSI), Rumer, E. (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), Tenenbaum, E. (Institut Français des Relations Internationales), Thomas, T. (Foreign Military Studies Office, Ft. Leavenworth); Vatanka, A. (Middle East Institute, The Jamestown Foundation), Weyers, J. (iBrabo; University of LIverpool), Yager, M. (NSI)

Question (QL5): What are the predominant and secondary means by which both large (macro-globally outside the CJOA, such as European, North African and Arabian Peninsula) and more targeted (micro- such as ISIL-held Iraq) audiences receive ISIL propaganda?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

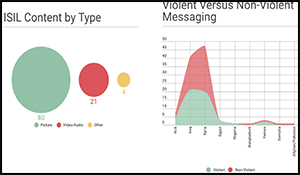

The contributors to this Quick Look demonstrate clearly the breadth and diversity of the ISIL media and communication juggernaut identifying a wide variety of targeted audiences, media forms and distribution mediums for both local and global audiences.

Smartphones are game-changers; the predominant distribution medium globally and locally

There was general acknowledgement among the experts that wide-spread, public access to smartphones has been both a game-changer for both the distribution and production of propaganda materials. Smart devices with web access were also cited by many as the predominant medium by which both global and local audiences receive ISIL propaganda and the catalyst for the fading of former distinctions between means used to communicate with “macro” versus “micro” audiences. Even ISIL messages primarily intended for local audiences (e.g., weekly newsletters) do not stay local; they are digitized and may be found on the internet and thus are available globally.

Chris Meserole a fellow at the Brookings Institution argues that ISIL communicators have benefitted from two particular capabilities that smart devices put in the hands of users: 1) easy access to impactful video and other visual content has enabled ISIL to transmit highly emotive and pertinent content in near real-time; and 2) users’ ability to produce and distribute their own quality images has altered the processes of recruitment and identity formation by making them more interactive: group members who formerly would have been information consumers only, now can readily add their voices to the group narrative by serving as information producers as well.

Cyber platforms are critical but consider Twitter and YouTube as starting points

Although Twitter, and YouTube are still the most commonly used platforms, and especially Twitter can be used for specifically-targeted, micro audiences, Gina Ligon who leads a research team at the University of Nebraska Omaha cautions that ISIL’s cyber footprint extends well beyond these “conventional” platforms which should be considered “mere starting points for its multi-faceted, complex cyber profile.” (See the Ligon et al below for ranks of the top cyber domains ISIL used between August 2015 and August 2016.)

It is important to note that although there is clearly increased local agency regarding production of ISIL communications, the teams from the University of Nebraska (Ligon et al), UNC-Chapel Hill (Dauber and Robinson) as well as Adam Azoff (Tesla Government) and Jacob Olidort (Washington Institute) find substantial evidence of centralized ISIL strategic control of message content. However, once content is approved, a good argument can be made that dissemination of ISIL messages and even video production is localized and decentralized. The result is a complex and “robust cyber presence.”

Static or moving images – key to evoking emotion — characterize all forms of ISIL propaganda

The most distinctive characteristic of ISIL propaganda is its high quality visual content which are easier to distribute than large texts. It is also easier to evoke emotion with an image than with text. Arguably, the most prolific and widely-distributed propaganda are ISIL’s colorful print and digital magazines (e.g., Dabiq, Rumiyah in English, Constantinople in Turkish Fatihin in Malay, etc.) It is well known that ISIL videos are extremely pervasive and an important form of ISIL messaging. However, multiple experts noted that the sophistication and production value of today’s videos are a far cry from the 2014-era recordings of beheadings that horrified the world.

Not everything is digitized: solely local propaganda forms and mediums

Audiences both in and outside ISIL controlled areas and those outside the region receive ISIL propaganda products. However, there are some mediums and forms of propaganda which can only be delivered in areas in which ISIL maintains strict control of information and in which it can operate more overtly. For example, ISIL has printed ISIL education materials and changed school curricula in its areas, it holds competitions and events to recruit young people, and polices strict adherence to shar’ia law (hisba). It is in this context that Alexis Everington (Madison-Springfield) argues, one of the most impactful forms of ISIL messaging remains its visible actions (of course, the perceived actions of Iraqi government forces, Assad forces, etc. and the US/West are likely equally, if indirectly, impactful). Second in importance are “media engagement centers such as screens depicting ISIL videos as well as mobile media trucks.” Outside ISIL controlled areas, NDU Professor of International Security Studies Hassan Abbas, cites “the word of mouth” including “gossip in traditional tea/food places” as still the primary means by which local audiences receive ISIL propaganda, and many experts agree that the content is “largely influenced by religious leadership.”

What happens next?

Finally, Adam Azoff of Tesla Government offers a caution regarding what happens when ISIL-trained, foreign media operators are pushed out of all ISIL-held areas: as these fighters relocate we should be prepared for the possibility that they would “continue their ‘cyber jihad’ abroad and develop underground media cells to continue messaging their propaganda. Though it will be more difficult to send out as large a volume of high-quality releases, it is not likely that ISIL will return to the amateurish and locally-focused media operations of 2011.”

Contributing Authors

Abbas, H. (National Defense University), Azoff, A. (Tesla Government), Church, S. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Dauber, C. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Derrick, D. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Des Roches, D. (National Defense University), Everington, A. (Madison Springfield Inc.), Gulmohamad, Z. (Sheffield University), Johnson, N. (University of Miami), Ligon, G. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Logan, M. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Meserole, C. (Brookings Institution), Olidort, J. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Robinson, M (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Warner, G. (University of Alabama at Birmingham)

Question (V5): Factors that Will Influence the Future of Syria. What are the factors that will influence the future of Syria and how can we best affect them?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Experts varied from pessimistic (chronic warfare) to cautiously optimistic regarding their expectations for the future of Syria, yet mentioned many of the same factors that they felt would influence Syria’s future path. Most of these key factors – ranging from external geopolitical rivalries to the health and welfare of individual Syrians – were outside what typical military operations might affect. Instead they center on political and humanitarian recovery, healing of social division.

External Factor: the use of Iranian, Saudi proxies in Syria

Iranian and Saudi use of proxy forces is one of the wild-cards in the future of Syria and is probably quickest way to reignite violence in the wake of any cease-fire or negotiated settlement. In fact, the intensity of the Iran-Saudi regional power struggle and how this might play out in Syria was the factor most mentioned by the SMA experts.

Encouraging the conditions necessary for stability in Syria requires discouraging Iran-Saudi rivalry in Syria. This can be done in a number of ways including offering for security guarantees or other inducements to limit proxyism in Syria (e.g., for Iran promise of infrastructure reconstruction contracts). Unfortunately, Iran stands to have greater leverage in Syria following the war, regardless of whether Assad stays or goes. If Assad or loyalist governors remain in Syria they will be dependent on Iran (and Russia) for financial and military support. As Yezid Sayigh (Carnegie Middle East Center) writes, “even total victory leaves the regime in command of a devastated economy and under continuing sanctions.” Still, if Assad is ousted and Iranian political influence in the country wanes, its economic influence in Syria should remain strong. Since at least 2014 Iran, the region’s largest concrete producer has been positioning itself to lucrative gain post-war infrastructure construction contracts giving it significant influence over which areas of Syria are rebuilt and which groups would benefit from the rebuild. Under these conditions, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and/or Turkey could ramp up their efforts to contain Iranian influence by once again supporting aggrieved Sunni extremists. This would be all the more likely, if as Josh Landis predicts, “Assad, with the help of the Russians, Chinese, Iraqis and Hezbollah, will take back most rebel held territory in the next five years.”

External Factor: the degree of Coalition-non Coalition agreement on the governance and security conditions of post-war Syria

Lt Col Mel Korsmo an expert in civil war termination from Air University concludes that a negotiated settlement is the best path to political transition and resolution of the civil conflict in Syria. Others felt that any resolution of the Syrian civil conflict would depend on broad-based regional plus critically, US and Russian (and perhaps Chinese) agreement on the conditions of that resolution. The first question is whether there remain any elements of 2012 Geneva Communiqué or UN Security Council resolution 2254 which endorsed a roadmap for peace in Syria that might be salvaged. Lacking agreement among the major state actors, the authors expected that proxy warfare would continue in Syria. Moshe Ma’oz (Hebrew University) and others however argued that it may be too late for the US to wield much influence over the future path of Syria; it has already ceded any leverage to Russia and Iran. Others argue that the way the US might regain some leverage is by committing to the battle against Assad with the same effort given to defeating ISIL. Nevertheless, there is general agreement that it is imperative to attempt now to forge agreement on the clearly- stated steps to implementing a recovery plan for Syria.

External Factor: US and Coalition public support for sustained political, security and humanitarian aid for Syria

Another condition that must be met if the US and Coalition countries are to have impact on political and social stability in Syria is popular support for providing significant aid to Syria over an extended period of time. This may be a tall order, particularly in the US where the public has long thought of Syria as an enemy of Israel and the US in the Levant. Compounding this, the experts argue that when warfare comes to an end in Syria the regime will be so dependent on Russia (and Iranian) aid, that the Syrian government will lose its autonomy of action. While encouraging Americans to donate to charitable organizations aiding Syrian families may not be too difficult, gaining support for sustained US government assistance in the amounts and over the length of time required is likely to be a significant challenge. It is also one that could be quickly undermined by terror attacks emanating from the region.

Internal Factor: the role of Assad family

Osama Gharizi of the United States f Peace points to the “‘current strength and cohesion” of the Syrian opposition and argues that a “disjointed, weakened, and ineffectual opposition is likely to engender [an outcome] in which the Syrian regime is able to dictate the terms of peace” –a situation which would inevitably leave members of the family or close friends of the regime in positions of power. Unfortunately, many of the experts believe that while there may be fatigue-induced pauses in fighting, as long as the Assad family remains in power in any portion of Syria civil warfare would continue. Furthermore separating Syria into areas essentially along present lines of control would leave Assad loyalists and their Iranian and Russian patrons in control of Damascus and the cities along the Mediterranean coast with much of the Sunni population relegated to landlocked tribal areas to the east. Such a situation would further complicate the significant challenge of repatriating millions of internally displaced persons (IDPs), many of whom lived in the coastal cities.

Acceding to Assad family leadership over all or even a portion of Syria is unlikely to offer a viable longer-term solution, unless two highly intractable issues could be resolved: 1) the initial grievances against the brutal minority regime had been successfully addressed; and 2) the Assad regimes’ (father and son) long history of responding to public protest by mass murder of its own people had somehow been erased. The key question is how to remove the specter of those associated with Assad or his family who would invariably be included in a negotiated transition government. Nader Hashemi of the University of Denver suggests that US leadership in the context of the war in Bosnia is a good model: “the United States effectively laid out a political strategy, mobilized the international community, used its military to sort of assure that the different parties were in compliance with the contact group plan … it presided over a war crimes tribunal …” In his view, prosecuting Assad for war crimes is an important step.

Internal Factor: What is done to repair social divisions and sectarianism in Syria

Nader Hashemi (University of Denver) and Murhaf Jouejati (Middle East Institute) observe that the open ethnic and sectarian conflict that we see in Syria today has emerged there only recently – the result of over five years of warfare, war crimes committed by the Alawite-led government, subsequent Sunni reprisals, the rise of ISIL and international meddling. As a result, there is now firmly-rooted sectarian mistrust and conflict in Syria where little had existed before. Other than pushing for inclusive political processes and rapid and equitable humanitarian relief, there is little that the US or Coalition partners will be able do about this in the short to mid-term. As Hashemi says, healing these rifts will be “an immense challenge; it will be a generational challenge; it will take several generations.” On the brighter side, he also allows that in his experience most Syrians “are still proud to be Syrians. They still want to see a cohesive and united country.” While separation into fully autonomous polities is untenable, reconfiguring internal administrative borders to allow for “localized representation” and semi-autonomy among different groups may be a way to manage social divisions peacefully.

Internal Factor: Demographics and a traumatized population

There is a youth bulge in the Syrian population. Add to this that there is a large segment of young, particularly Sunni Syrians who have grown up with traumatic stress, have missed years of schooling so are deficient in basic skills, have only known displacement and many of whom have lost one or both parents in the fighting. There is hardly a more ideal population for extremist recruiters. Murhaf Jouejati (Middle East Institute) calls this “a social recipe for disaster” that he believes in the near future will be manifest in increased crime and terrorist activity. As a consequence, it is important for the future of Syria and the region to assure that children receive education, sustained counseling and mental health services and permanent homes for families and children.

Contributing Authors

Sayigh, Y. (Carnegie Middle East Center), Jouejati, M. (National Defense University), Ma’oz, M. (Hebrew University, Jerusalem), Hashemi, N (Center for Middle East

Studies, Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver), Landis, J. (University of Oklahoma), Korsmo, M. (Lemay Doctrine Center, Air University),

Gharizi, O. (United States Institute of Peace)

Question (V6): Strategic and Operational Implications of the Iran Nuclear Deal. What are the strategic and operational implications of the Iran nuclear deal on the US-led coalition¹s ability to prosecute the war against ISIL in Iraq and Syria and to create the conditions for political, humanitarian and security sector stability?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Prior to the signing of the Iran Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July 2014, Iran watchers tended to anticipate one of two outcomes. One camp expected a reduction in US-Iran tensions and that the JCPOA might present an opening for improved regional cooperation between the US-led coalition and Iran. The other camp predicted that Iran would become more assertive in wielding its influence in the region once the agreement was reached.

Implications of JCPOA for the Near-term Battle: Marginal

Iran experts in the SMA network generally believe that JCPOA has had negligible, if any, impact on Iran’s strategy and tactics in Syria and Iraq.1 While Iran does appear to have adopted a more assertive regional policy since the agreement, the experts attribute this change to regional dynamics that are advantageous to Iran, and Iran having been on “good behavior during the negotiations” rather than to Iran having been emboldened by the JCPOA. Patricia Degennaro (TRADOC G27) goes a step further. In her view, the impact of the JCPOA on the battle against ISIL is not only insignificant, but concern about it is misdirected: “the JCPOA itself will not impede the Coalition’s ability to prosecute the war … and create the conditions for political, humanitarian and security sector stability. Isolation of Iran will impede the coalition’s mission.”

Richard Davis of Artis International takes a different perspective on the strategic and operational implications of the JCPOA. He argues that Saudi, Israeli and Turkish leaders view the JCPOA together with US support for the Government of Iraq as evidence of a US-Iran rapprochement that will curb US enthusiasm for accommodating Saudi Arabia’s and Turkey’s own regional interests. Davis expects that this perception will “certainly manifest itself in the support for proxies in Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Specifically, it means that Saudi Arabia and Turkey will likely be more belligerent toward US policies and tactical interests in the fight to defeat ISIL.”

Implications of JCPOA for Post-ISIL Shaping: Considerable Potential

The SMA experts identified two ways in which the JCPOA could impact coalition efforts to stabilize the region in the mid- to longer-term: 1) if Iran were to use it as a means of generating friction in order to influence Coalition actions for example by convincing Coalition leaders that operations counter to Iranian interests (e.g., in Syria) could jeopardize the JCPOA; and, 2) indirectly, as having created the sanction relief that increases Iranian revenue and that can be used to fund proxy forces and other Iranian influence operations.

Provoking Friction as a Bargaining Chip. A classic rule of bargaining is that the party that is more indifferent to particular outcomes has a negotiating advantage. At least for the coming months, this may be Iran. According to the experts, Iran is likely to continue to use the JCPOA as a source of friction – real, or contrived – to gain leverage over the US and regional allies. The perception that the Obama Administration is set on retaining the agreement presents Tehran with a potent influence lever: provoking tensions around implementation or violations of JCPOA that look to put the deal in jeopardy, but that it can use to pressure the US and allies into negotiating further sanctions relief, or post-ISIL conditions in Syria and Iraq that are favorable to Iran. However, because defeat of ISIL and other groups that Iran sees as Saudi-funded Sunni extremists,2 the experts feel that if Iran were to engage in physical or more serious response to perceived JPCOA violations, they would choose to strike out in areas in which they are already challenging the US and Coalition partners (e.g., at sea in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea; stepping up funding or arms deliveries to Shiite fighters militants in Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Yemen) rather than in ways that would actually impede ISIL’s defeat.

Increased Proxy Funding. Iran has often demonstrated a strategic interest in maintaining its influence with Shi’a communities and political parties across the region, including of course, providing support to Shi’a militia groups (Bazoobandi, 2014).3 Pre-JCPOA sanctions inhibited Iran’s ability to provide “continuous robust financial, economic or militarily support to its allies” according to Patricia Degennaro (TRADOC G27). An obvious, albeit indirect implication of the JCPOA sanctions relief for security and political stability in Iraq in the longer term is the additional revenue available to Iran to fund proxies and conduct “political warfare” as it regains its position in international finance and trade.4 It will take time for Iran to begin to benefit in a sustainable way from the JCPOA sanctions relief. As a result it is not as likely to be a factor in Coalition prosecution of the wars in Iraq and Syria, but later, in the resources Iran can afford to give to both political and militia proxies to shape the post-ISIL’s region to its liking.

Contributing Authors

DeGennaro, P. (Threat Tec, LLCI -TRADOC G27), Nader, A. (RAND), Eisenstadt, M. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Knights, M. (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Alex Vantaka (Jamestown Foundation)

Operating in the Human Domain 1.0.

Author | Editor: U.S. Special Operations Command.

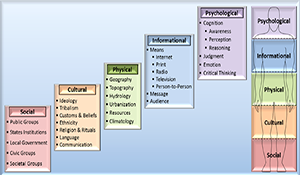

Building on the vision of USSOCOM strategic guidance documents, the Operating in the Human Domain (OHD) Concept describes the mindset and approaches that are necessary to achieve strategic ends and create enduring effects in the current and future environment. The Human Domain consists of the people (individuals, groups, and populations) in the environment, including their perceptions, decision-making, and behavior. Success in the Human Domain depends on an understanding of, and competency in, the social, cultural, physical, informational, and psychological elements that influence human behavior.2 Operations in the Human Domain strengthen the resolve, commitment, and capability of partners; earn the support of neutral actors in the environment; and take away backing and assistance from adversaries. If successful in these efforts, Special Operations Forces (SOF) will gain military, political, and psychological advantages over their opponents. The OHD Concept integrates existing capabilities and disciplines into an updated and comprehensive approach that is applicable to all SOF core activities.

SOF personnel continuously think about human interactions, building trust, and winning support among individuals, groups, and populations. Drawing on the approach and required capabilities identified in this concept, SOF and its partners use persuasion and compulsion to shape the calculations, decision-making, and behavior of relevant actors3 in a manner consistent with mission objectives and the desired state.4 SOF must win support and build strength, before confronting adversaries in battle. Working in collaboration with capable partners and as part of a whole-of-government approach, SOF enables preemptive actions to avert conflicts or keep them from escalating. When necessary, SOF and its partners confront and defeat adversaries, always mindful that the end goal is an eventual cessation of hostilities and a more sustainable peace.

SOF conduct enduring engagement in a variety of strategically important locations with a small-footprint approach that integrates a network of partners. This engagement allows SOF personnel to nurture relationships prior to conflict. Language and cultural expertise are important, but SOF’s ability to shape broader campaigns with allies and partners to promote stability and counter malign influence is vital. SOF leaders plan and execute operations that support national objectives, while providing continuous analysis and advice to ensure effective strategy. SOF must identify and assess relevant actors, understand their past and current decisions and behavior, and anticipate and influence their future choices and actions across the ROMO.

SOF contribute to the accomplishment of U.S. policy objectives during peaceful competition, non-state and hybrid conflicts, and wars among states. The ideas in the OHD Concept are key to confronting state and non-state actors that combine conventional and irregular military force as part of a hybrid approach. Adversary states are increasingly adapting their methods to negate current and future U.S. strengths, relying on non-traditional strategies, including the use of subversion, proxies, and anti- access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. These adversary strategies require a refined U.S. approach for effective counteraction. A critical goal will be to create conditions that shape adversary decisions and behavior in a manner that favors U.S. objectives or develops opportunities friendly forces can exploit to achieve the desired state.

Mosul Coalition Fragmentation: Causes and Effects.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc) & Krakar, J. (TRADOC G-27).

This paper assesses the potential causes and effects of fragmentation on the Counter-ISIL coalition. This coalition consists of three distinct but interrelated subsets:

- the CJTF-OIR coalition;

- the regional coalition, de facto allies of convenience, who may provide any combination of money, forces or proxies;

- the tactical coalition, the plethora of disparate groups fighting on the ground.

The study team assessed how a change in either the CJTF-OIR coalition or regional coalition could influence the tactical coalition post Mosul and the subsequent effect of these potential fragmentations on the GoI¹s ability to control Iraq. The study team established six potential post-Mosul future scenarios. One future consisted of the tactical coalition remaining intact and the other five consisted of different permutations of the tactical coalition fragmenting. The study team then modeled these six futures with the Athena Simulation and quantified their effects on both Mosul and Iraq writ large.

During simulation these six fragmentation scenarios collapsed into two distinct outcomes: one in which GoI controlled Mosul and one in which local Sunni leadership controlled Mosul. The variable that determined the outcome was the involvement of the Sunnis in the post-Mosul coalition—if the local Sunni leadership remained aligned with the GoI, the GoI remained in control of Mosul. If the local Sunni leadership withdrew from the coalition the GoI lost control of Mosul and the local Sunni leadership assumed control of Mosul—regardless of whether any other groups left the coalition. Irrespective of the local Sunni leadership’s involvement in the coalition the GoI was able to maintain control of everything but Mosul and the KRG controlled areas of Iraq. This included historically Sunni areas of Al Anbar including Fallujah and Ramadi.

While several permutations of the regional coalition fragmenting may take place, the centrality of the Sunnis to any outcome puts the actions of the GoI to forefront. PM Abadi’s desire to preserve the unity of Iraq may position the GoI at odds with calls for increased local autonomy from some factions of Kurdish and Sunni leaders. In the event of the chaos that would characterize violent civil conflict among Kurdish, Sunni and Shi’a forces—likely with proxy support from Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran respectively—the multi-ethnic, multi-sect members of the Iraqi Army and police will be hard pressed to know which battles to fight and more than breaking with the coalition outright, may for reasons of confusion and self-preservation simply fall and recede as effective fighting forces.

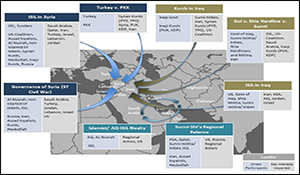

Unpacking the Regional Conflict System surrounding Iraq and Syria—Part I: Characterizing the System.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

This is Part I of a larger study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. It describes the system and why it is critical to assess U.S. security interests and activities in the context of the entire system rather than just the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the U.S. is most interested. Part II describes the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actor over five of the eight conflicts. The final results are presented in a Power Point briefing.

The nature of “the” conflict, or: Why there are no sides

At the beginning of U.S. involvement in the war against ISIL, many U.S. analysts and planners tended to treat the defeat of ISIL as two issues: defeating ISIL in Syria and defeating ISIL in Iraq. There are good reasons for the initial focus on Iraq, including the more significant U.S. interests, relations and sunk costs. As ISIL’s territorial gains progressed, however, the situation became more commonly viewed as a single, cross-border conflict. The reason the conflict engulfing Syria and Iraq is so difficult to grasp is that what many view as one or two conflicts is in reality a complex web of at least eight distinct militarized disputes happening simultaneously in pretty much the same space.1 While some of the conflicts have overlapping participants, possible outcomes, and similar interests, none of the eight are the same on all counts.

We misdirect ourselves if we insist on looking for a consistent alignment of actors – “sides” – across this complex, overlapping and multi-tiered system. Because the same actor can have different widely interests at stake in different conflicts we cannot assume a priori that co-participants like Hezbollah and the U.S. who share preferences over certain outcomes (e.g., the defeat of ISIL in Syria) in one or more of the conflicts will share objectives in the others. Analysis of the actors interests that shape events in the region shows actors can sometimes agree on which is the worst outcome in a given dispute, while being in serious disagreement over which is the best outcome in that same dispute. For example, in the Syrian Civil War Jaish al Fatah and the Assad regime agree that ISIL should not be allowed to expand the self- proclaimed Caliphate over large areas of Syrian territory; however they disagree intensely over who should govern Syria. The reverse can also be true: Turkey, the U.S. and the non-Islamist Syrian opposition might agree that the best outcome in the Syrian Civil War would be replacing the regime with leaders from the non-Islamist Syrian opposition; because they have different arrays of core interests there is less agreement over whether the worse outcome would be the fall of the regime accompanied by ISIL expansion, or, Assad’s regaining control in Syria.

Why is this important? First, coming to grips with these differences – what we might think of as the limits or tipping points of cooperation between actors – is critical for estimating what other actors may do in response to changing conditions in the region. Second, failure to appreciate and manage the broader context within which our counter-ISIL efforts occur leaves us vulnerable to missteps and strategic surprise simply because we have not considered the impact of our actions beyond the battle against ISIL. In fact, looking more broadly highlights a number of scenarios in which the defeat of ISIL, for example accomplished by further alienating the Sunni minority from any political system in Iraq, or by tipping the balance in Iran-Saudi power politics, would actually do more damage to our counter- terror efforts than not having done so.

The remainder of Part I outlines the core issues for eight militarized disputes in the conflict system. To demonstrate what we may fail to recognize about the broader threats to US interests we consider the impact of the total defeat of ISIL in Syria and Iraq on the regional conflict system.

Unpacking the Regional Conflict System surrounding Iraq and Syria—Part II: Method for Assessing the Dynamics of the Conflict System, or, There are no sides—only interests.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

This is Part II of a larger study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. Part I described the system and why it is critical to assess US security interests and activities holistically rather than just in terms of the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the US is most interested. Part II described the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actors for five conflicts. It uses the Syrian Civil War as a use case.

In this region in particular, the absence of warfare does not translate either to stability or to peace. As former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Dempsey suggested in testimony to Congress1, the key question is not how to manage or avoid warfare in the Middle East, but which are the general conditions for peace and stability and what might the US and international community do – or avoid doing – in order to promote those.

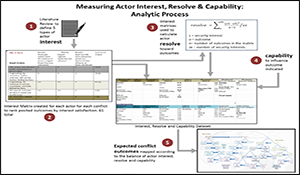

What are the dynamics embedded in the region’s current conflicts that will drive it toward one future or another? The outcomes of conflicts are not the result of a single actor’s actions or desires, but are a product of the interactions of opponents; the forces that determine one or another regional future reflect the confluences of actors’ interests, capabilities and resolve. Thus, one way to assess the dynamics that propel the system is to consider three factors that condition the behaviors of state, sub-state and non-state actors:

- Interests — the various security, political, social, economic, and influence interests that an actor perceives to be at stake;

- Capability — the ability to directly influence or cause an outcome to occur; and

- Resolve — the intent or willingness to do so.

The alignment of interests between actors will determine the set of potential outcomes for any particular regional or sub-regional event. However, common interests or alignments between actors may vary across events or conflicts; we cannot assume that a preference for the same outcome in one event will result in shared interests among the same actors in other events. While the alignment of actor interests determines possible outcomes, the distribution of actor resources and resolve across those outcomes governs the likelihood that an outcome will emerge. In other words, the dynamics that determine one or another future reflect the confluences of actors’ interests, resources and resolve.

How stable that outcome is likely to be, however, will be determined not so much by the resources of those who support it, but the resources of those who oppose it. By considering the actors whose interests are blocked or destroyed by a particular outcome, we can also gain insight into the potential durability of a particular outcome. In short, the outcome of a conflict is a function of the interests and preferences of the actors with the greatest resources and resolve relative to that conflict. The durability of that outcome on the other hand, is determined by the resources and resolve of those whose interests remain unfulfilled by the outcome. In shorthand the analytic model is this: Interest + Resolve + Capability = Expectations for the Region.

Part IV: Analysis of the Dynamics of Near East Futures: Assessing Actor Interests, Resolve and Capability in 5 of the 8 Regional Conflicts.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

This briefing is the final part of a four-part study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. Part II describes the system and why it is critical to assess U.S. security interests and activities in the context of the entire system rather than just the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the U.S. is most interested. Part II describes the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actor over five of the eight conflicts. Part IV presents the results of the interest, resolve, capability assessment.