NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

Unpacking the Regional Conflict System surrounding Iraq and Syria—Part III: Implications for the Regional Future: Syria Example of Actor Interests, Resolve and Capabilities Analysis.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

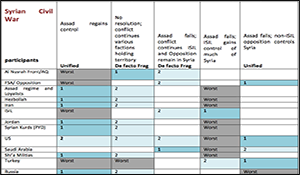

This is Part III of a larger study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. Part I described the system and why it is critical to assess US security interests and activities holistically rather than just in terms of the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the US is most interested. Part II described the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actors for five conflicts. It uses the Syrian Civil War as a use case.

This paper presents the analysis of the Syrian Civil War to illustrate the analytic process that was applied to 20-plus actors over five regional conflicts in and around Syria and Iraq: 1) The Syrian Civil War; 2) the battle to Defeat ISIL in Syria; 3) the battle to Defeat ISIL in Iraq; 4) the Iran-Saudi Regional Rivalry; and, 5) the conflict over domestic control among the Shi’a hardline, Kurds, Abadi Government and Sunni tribal leaders. It looks in detail at the actor interests involved in the Syrian Civil conflict and includes the top-level findings assessment, characterization of the conflict based on the interests at stake, description of the posited outcomes, a summary of the preferences over those outcomes for each participating actor and a discussion of the implication of actor resolve and capabilities.

Promoting greater stability in post-ISIL Iraq, Volume 2: Why do groups form and why does it matter for stability in Iraq? When the social becomes political.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

United States Central Command (CENTCOM) posed the following question to the Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) virtual reach back cell: What opportunities are there for USCENTCOM to shape a post-ISIL Iraq and regional security environment, promoting greater stability? To address this question, in volume 1, we examine the drivers of legitimacy, security, and social accord for key Iraqi stakeholders. In the current volume 2, we provide an in-depth and comprehensive discussion of the key social elements and dynamics contributing to social accord, and tie the social domain to the political domain in Iraq, with accompanying implications for stability.

Promoting greater stability in post-ISIL Iraq, Volume 1: Analysis of the drivers of legitimacy, security, and social accord

for key Iraqi stakeholders.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

United States Central Command (CENTCOM) posed the following question to the Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) virtual reach back cell: What opportunities are there for USCENTCOM to shape a post-ISIL Iraq and regional security environment, promoting greater stability? Analyses of the security challenges facing post-ISIL Iraq frequently emphasize two central points. The first of these is that any security solution must address the political concerns and goals of key actors. This report is focused on providing insight into not only security factors, but also those political and social factors that have follow-on effects for the security domain. The second point is that both political interests and security interests are highly localized. We acknowledge the tremendous variation in interest groups within the social and political landscape in Iraq. At the same time, social science methodologies are oriented around making sense of such fragmentation, by looking for commonalities within and across societies. While no generalization will ever cover every possible case or variation, the common themes that are derived will represent likely scenarios. Toward this goal, we focus here on the broad ethno-sectarian divisions that are often currently in use in Iraq: Sunni, Shia, and Kurd. Where possible, we seek to specify relevant subgroups (e.g., Shia-led militia, Peshmerga, Sunni tribal elites). While we recognize that there is variation both within and even entirely outside of these groups, the discussion and insights here capture the interests and grievances of a wide segment of the Iraqi population as a whole.

The provision of security is one of the fundamental functions of all governments, and as such, contributes directly to governing legitimacy. For a country such as Iraq, emerging from a period of conflict with unresolved and highly salient sectarian divisions, the relationship between security and governing legitimacy is even more critical for stability. If key stakeholders do not perceive the national government to be legitimate, they are unlikely to trust that that government will meet their security needs. A post-ISIL Iraq will face a complex security environment with multiple government and militia forces identifying with Shia, Kurdish, and Sunni populations as much as, and in some cases more than, with the Iraqi state. Given the recent history of sectarian competition and conflict surrounding Iraq’s security apparatus and national government, political reconciliation between Kurds, Shia, and Sunni, irrespective of the institutional form that takes, will be essential for creating short term stability (ending open conflict). Moreover, the achievement of a more general social accord is a necessary condition for the development of a cohesive national identity. Common national identity (not to be confused with nationalism) increases the legitimacy of national government, and as such, is an important foundation for longer-term political stability.

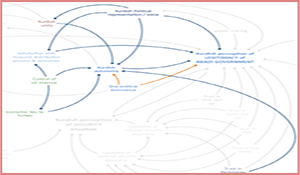

This report presents insights from the analysis of a set of qualitative loop diagrams1 of the security dynamics for Kurds, Shia, and Sunni, constructed around social accord and governing legitimacy in Iraq. The relationships and feedback loops for each of the key stakeholders (Shia, Kurd, and Sunni) have been developed through the application of NSI’s StaM model.2 Our analysis for this report focuses specifically on the dynamics that drive the security and stability challenges facing Iraq post-ISIL. Our analysis indicates that, for each group, there is a key interest—both driving and driven by their relations with other groups—that is central to understanding how the security-legitimacy relationship manifests for that group. For the Sunni, it is their perception of equality (or lack thereof) and fear of retribution; for the Shia, their drive to maintain political dominance, and for the Kurds, their desire for greater autonomy.

A qualitative loop diagram is a visual heuristic for grasping complex recursive relationships among factors, and is a useful means of uncovering unanticipated or non-intuitive interaction effects embedded in complex environments such as that we see in Iraq. It is intended to serve as a “thinking tool” for analysts, practitioners, and decision makers. Once produced, the “map” of the direct and indirect relationships between legitimacy, social accord, and Iraqi perceptions of security, can be used to explore those relationships, test hypotheses about them, and provide a broad picture of second- and third-order effects on critical nodes in the system. For CENTCOM and others involved in building stability in Iraq, a clear understanding of the system that links Iraqi politics and social relations to security is a critical prerequisite for identifying areas in which CENTCOM activities might have the greatest positive impact and those where the risk of unintended consequences is highest.

The report is organized in two volumes: Volume 1, here, presents the detailed insights of the loop diagram analyses, along with a discussion of key areas of opportunity or risk mitigation for CENTCOM, while Volume 2 provides a more in-depth and comprehensive discussion of the key social factors that significantly impact the political domain, and thus ultimately, stability in Iraq. Traditionally, the social scientific emphasis when examining issues of security has been heavily rooted in international relations and politics. In more recent years, additional layers of insight have been added from anthropology, sociology, and psychology. Here, we take a heavily social psychological approach to examining the social domain, though we continue to incorporate concepts from across the social science disciplinary spectrum. The utility of this work is enhanced by the loop diagram methodology—which emphasizes looking at cross-cutting effects both within and across the major domains of interest—and generates new insights about the reciprocal and balancing effects that exist among these social, political, and security domains. This enables a more transparent assessment of relationships both between and within specific groups.

Before turning to the loop diagrams, however, a brief discussion of the concepts of social accord and legitimacy in the context of Iraq is warranted. This is followed by a discussion of important features and nodes excerpted from the complete loop diagrams for Kurds, Shia, and Sunni.3 The final section presents general findings across the various subgroups, and identifies risks and opportunities associated with CENTCOM and other US efforts to shape the security environment and promote stability in post-ISIL Iraq.

Question (R2 Special): What are indicators of change in Russian strategic interests in Syria?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

This paper found that Russia¹s strategic interests in the Middle East are fairly stable. What could change is how Russia prioritizes its interests in the wake of the US election and change in administration. Indicators of change might include troop movement or alteration in leader discourse.

Russia’s strategic interests in Syria are fairly stable

Timothy Thomas, a Russia expert from the Foreign Military Studies Office and former US Army Foreign Area Officer (FAO) believes that a fair articulation of Russia’s long-term strategic interests is right where they should be: in the country’s 2015 National Security Strategy (NSS).1 The only “changes” that Thomas expects will be the result of the “gradual accomplishment” of several interests. First among these is strengthening Russian national defense, which in Syria has meant Russian forces taking the opportunity to test new weapons systems and command procedures while working to keep ISIL and Islamic extremists from Russia’s southern borders. Second, Thomas reports that “consolidating the Russian Federation’s status as a leading world power” in a multipolar international system has been accomplished by Russian actions in Syria and Ukraine “in the eyes of many nations.”

What could change? How Russia prioritizes its interests

Thomas points to optimistic versus pessimistic Russian views on how the recent US election will impact US policy in Syria. Optimistically, some feel that the election of Donald Trump may diminish the US security threat, offer Russia new opportunities in the region, and thus allow Russia to prioritize other interests than it has been. This logic is based in the belief that the new US Administration will be willing to tolerate Assad in order to work in concert with Russia to defeat terrorist threat from ISIL and other groups. Russians taking a more pessimistic view however argue that forging a US-Russia partnership in the region will not be as simple as a change of Administration.

What might signal a change?

Dr. Patricia Degennaro (Threat Tec, LLCI -TRADOC G27) believes that “the key to understanding signals for change include Russian rhetoric and key troop maneuvers. The Russian President’s messaging is the signal to change.” Dr. Larry Kuznar (Indiana-Purdue; NSI) reports empirical analysis of President Putin’s language use and whether Putin’s language patterns might be used as indicators of Russian change of strategy in Syria. Dr. Kuznar uncovers a “blip” then “brag” pattern in Putin’s public discourse that may be used as an indicator. Specifically, Kuznar finds that prior to a major event (like invading Ukraine) Putin begins mentioning a few key emotional themes (e.g., pride, protection, unity, strength and Russian superiority) and political themes (e.g., Russian security, Russia’s adversaries, Russian energy), a “blip,” then goes silent presumably during the planning and execution phase. Once the activity or goal is complete however, Kuznar finds that “Putin is characteristically tight-lipped about his interests and intentions, but tends to brag after he achieves a victory.” He habitually “relaxes his restraint and releases a rhetorical flourish of concerns and emotional language”, i.e., some major bragging.

In short, Dr. Kuznar (Indiana-Purdue) finds an empirical basis to suggest that specific linguistic themes such as pride, Russian superiority and France2) as well as more general emotional and political themes “may serve as early indicators and warnings of Putin’s intent.” Currently Putin’s mention of pragmatic themes in relation to Russian energy resources and his recent concern with Turkey, and emotive themes, such as the threat of Nazism, may serve as indicators of his activities if his past patterns are retained. And as such, “may have direct implications for his intentions in Syria.”

Contributing Authors

Kuznar, L. (NSI & Indian University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Thomas, T. (Foreign Military Studies Office, US Army), (TRADOC), Degennaro, T. (Threat Tec, LLCI – TRADOC G27)

Options to Facilitate Socio-Political Stability in Syria and Iraq.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc) & Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff).

This White Paper presents the analytic results from Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) project touching on the Middle East and North Africa. The objective is to suggest options to manage conflict in the region and to facilitate socio-political stability in Iraq and Syria. Options that are discussed are intentionally “out-of-the-box”, non-kinetic, and focused on potential Coalition efforts to:

- Diminish the allure of the ideology that Da’esh presents to radicalized and potentially radicalized and other youth in the region; and

- Shape the context to best support reduced regional turmoil and defeat of the Da’esh organization while minimizing the risk of further spread of the jihadist ideology.

The findings are the result of the SMA’s standard multi-disciplinary approach and belief that no single discipline by itself can provide a comprehensive approach to this global and regional conundrum. The analyses were conducted unconstrained by policy, legal, and operational consideration and attempts were made to garner insights from historical precedent.

Following are brief summaries of the articles in this white paper.

In his opening article, Mr. Bob Jones (SOCOM) argues that we live in revolutionary times and ISIL leverages the energy in Sunni populations to their advantage. In revolutionary times, revisionist powers see and seize opportunities; while status quo powers tend to be defensive, reactive, and see agents of change as “threats.” Iran saw an opportunity to expand its sovereign privilege across the region with the fall of Saddam Hussein. Al Qaeda saw opportunity to reduce foreign influence, remove corrupt autocrats, and restore dignity to the Ummah; Da’esh saw the opportunity to best AQ in Syria and Iraq by offering “Caliphate today” in lieu of AQ’s more patient approach.

In his article entitled “Managing the Strategic Context in the Middle East: A Preliminary Transitivity Analysis of the Middle Eastern Alliance Network and Its Operational Implications“, Dr. Larry Kuznar advances balance theory to gauge the overall stability of the conflict system that surrounds the battle against Da’esh in Syria and Iraq. This system is characterized by multiple simultaneous conflicts engaging numerous state and non-state groups in the region and from outside of the region. The analysis focuses on the relations between 24 of the key state and non-state actors in this system and indicates that the region is locked in a well-established system of conflict that is likely to persist given the high degree of transitivity in established relationships.

In “An Analysis of Violent Nonstate Actor Organizational Lethality and Network Co-Evolution in the Middle East and North Africa”, Drs. Victor Asal, Karl Rethemeyer (SUNY Albany) and Dr. Joseph Young (American University) use new data that spans the years 1998 to 2012 to model the behavior of violent non-state actors (VNSAs) in the Middle East. Using several statistical techniques, including network modeling, logit analysis, and hazard modeling, they show that governments can use strategies that influence a group’s level of lethality, their relationships with other groups, and how long and whether these groups become especially lethal.

In his “Countering the Islamic State’s Ideological Appeal”, Dr. Jacob Olidort (Washington Institute) discusses an options-focused assessment for policy and practitioner communities in the United States government concerning the ideological threat posed by the Islamic State. The paper examines the possible evolution of the Islamic State in the event that it loses its strongholds in Iraq and Syria, and the nature of the threat it could pose to Western targets and interests. The assessment is based on the recently-published Washington Institute report, Inside the Caliphate’s Classroom, as well as the author’s cumulative research on the texts and ideas of the Islamic State and other Salafi and Islamist groups.

In their paper entitled “Framework for Influencing Extremist Ideology”, Drs. Bob Elder and Sara Cobb (GMU) discuss negotiation research, drawing on rational choice theory which provides a wealth of findings about how people negotiate successfully. They also describe some of the pitfalls that have been associated with negotiation failures. Building on narrative theory, they attempt to expand the theoretical base of negotiation in an effort to address the meaning making processes that structure negotiation as the basis of a framework for influencing extremist ideology. This research is combined with decision-related research conducted in support of deterrence planning as a means to discover potential influence levers for possible use as a counter to extremist ideology. Recognizing that conflict resolution is complicated because it involves changing the story from within the interactional context from where it arises, the framework assumes a staged approach to address the narrative structure of the ideologically-based conflict which anchors the influence actions on the strategic positions and identities, embedded in the narrative logics of the key characters.

The focus of the article entitled “Off-Ramps for Da’esh Leadership: Preventing Da’esh 2.0”, by Dr. Gina Ligon, University of Nebraska Omaha and Dr. Jason Spitaletta, The John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is two-fold. First, they discuss the underlying theory of TMT (Top Management Team) collaboration, and provide practitioners with some tactics to foment barriers and distrust to aid the operations meant to degrade the organization (e.g., retaking of Mosul). Second, given their analysis of what motivated each of these leaders to join and remain in Da’esh, they provide a set of tailored off-ramps to be considered to deter captured leaders from reconstituting Da’esh 2.0.

In their article entitled “Comprehensive Communications Approach,” (excerpted from their 2016 report, “Examining ISIS Support and Opposition Networks on Twitter,” available at http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1328.html), Drs. Todd Helmus and Elizabeth Bodine- Baron (RAND) argue the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), like no other terrorist organization before, has used Twitter and other social media channels to broadcast its message, inspire followers, and recruit new fighters. Though much less heralded, ISIS opponents have also taken to Twitter to castigate the ISIS message. Their article draws on publicly available Twitter data to examine this ongoing debate about ISIS on Arabic Twitter and to better understand the networks of ISIS supporters and opponents on Twitter in order to craft more effective counter-messaging strategies.

Finally, in “A Human Geography Approach to Degrading ISIL” Dr. Gwyneth Sutherlin (Geographic Services Inc.) argues that stabilizing the region and degrading ISIL will be an international effort with geopolitical and large network engagements. Ultimately, the activities proposed will have an impact for families and their homes on the ground in Syria and Iraq; therefore, the perspectives and priorities of these populations should be foregrounded in any approach, including the involvement of key stakeholders from the earliest possible phase, to lay the groundwork and build partnerships for the long-term stabilization process.

Contributing Authors

Asal, V. (SUNY Albany), Bodine-Baron, E. (RAND), Cobb, S. (George Mason University), Elder, R. (George Mason University), Helmus, T. (RAND), Jones, R. (SOCOM), Kuznar, L. (NSI, Indiana – Purdue U Fort Wayne), Ligon, G. (Univ. of Nebraska Omaha), Olidort, J. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Rethemeyer, K. (SUNY Albany), Spitaletta, J. (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory), Sutherlin, G. (Geographic Services, Inc.), Young, J. (American University)

Specifying and systematizing how we think about the Gray Zone.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., Polansky (Pagano), S., & Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc).

In their continued work on the changing nature of the threat environment General Votel et al (2016) forecast that the majority of threats to US security interests in coming years will be found in a “gray zone” between acceptable competition and open warfare. They define the gray zone as “characterized by intense political, economic, informational, and military competition more fervent in nature than normal steady-state diplomacy, yet short of conventional war,” (pp. 101). While this characterization is a useful guide, it is general enough that efforts by planners, scholars and analysts to add the level of specificity needed for their tasks can generated considerable variation in how the term is applied, and to which types of actions and settings it applies.

What lies between acceptable competition and conventional war?

Far from an unnecessarily academic or irrelevant question, this is a critical question. How we define a condition or action, in other words the frame through which we are categorizing certain actions as threatening rather than “normal steady-state” impacts what we choose to do about them. The “I know it when I see it” case-by-case determination of gray vs not gray limits identification of gray zone actions to those that have already occurred. Gaining some clarity on the nature of a gray zone challenges is essential for effective security coordination and planning, development of indicators and warning measures, assessments of necessary capabilities and authorities and development of effective deterrent strategies.

The ambiguous nature of the gray zone and the complex and fluid international environment of which it is a part, make it unlikely that there will be unanimous agreement about its definition. Our first goal in this paper then, is to describe the gray zone as much as define it. We begin with a review the work of a number of authors who have written on the nature and characteristics of gray zone challenges, and use these to identify areas of consensus regarding the characteristics of the gray space between steady-state competition and open warfare. We next use these to suggest a more systematic process for characterizing different shades of gray zone challenges.

Identification of Security Issues and their Importance to Russia, Its Near-abroad and NATO Allies: A Thematic Analysis of Leadership Speeches.

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. & Yager, M. (NSI, Inc).

This study addresses key questions posed in the SMA EUCOM project by using thematic analysis of speeches from leaders of state and non-state polities in Eastern Europe, Russia, and the Caucasus. The importance of an issue is measured by the density (mentions/words in speech) with which it is mentioned and the use of associated emotive language.

Key Findings by EUCOM Questions

Regional Outlook

Q04. Who are Russia’s allies and clients and where is it seeking to extend its influence within the EUCOM AOR?

Analysis of how strongly Russia’s allies express their allegiance to Russia and Russian culture indicates that Crimea is Russia’s staunchest ally. Transnistria also expresses a strong allegiance to Russia, followed by Donetsk. Luhansk and Armenia express pro- Russian sentiments, but only weakly.

Q10. How does Russia see its great power status in the 21st century?

Russian leaders do not mention aspirations for super-power status. Russia’s desire for great power status should be treated as a hypothesis that requires testing – it should not be assumed.

Q20. How might Russia leverage its energy and other economic resources to influence the political environment in Europe and how will this leverage change over the next 15 years?

Economic issues rank high in Russia’s security concerns. They express concern over the value of their energy resources, indicating that it is a key value. They often mention the reliance of European nations on Russian energy. To a lesser extent they mention expanding markets for their energy to Asia.

Media and Public Opinion

Q07. Conduct analysis of open source Russian media to understand key frames and cultural scripts that are likely to frame potential geopolitical attitudes and narratives in the region.

Cultural Frame: A key cultural frame that Russia and its allies use is their history of overcoming odds against aggressive adversaries to uphold their Russian independence. References to the need to defend Russians from the Nazi threat (historically and today) are used. Emotive Frame: Russia sees the US and NATO as a threat, and state that the US is conspiring against them.

Q08. How much does the U.S. image of Russia as the side that “lost” the Cold War create support for more aggressive foreign policy behavior among the Russian people?

Russia and its allies do not speak of losing to the West, but blame past leaders for giving away their power. Some leaders express nostalgia for Soviet power.

Q09. How might ultra-nationalism influence Russia’s foreign policy rhetoric and behavior?

As expected, Russian Nationalists, express nationalist sentiments strongly. However, both Putin and Lavrov use Russian nationalist arguments to some degree.

NATO

Q16. If conflict occurs, will NATO be willing and able to command and control a response?

NATO leaders use language in a manner (mention of security concerns, high emotive content) that indicates a relatively high commitment to addressing Russian threats.

The larger EUCOM effort integrates different teams’ findings in terms of how they relate to security issues, economic issues, domestic constraints, and prestige.

The security issues and themes identified through thematic analysis can be binned under these four interest areas and their densities analyzed. The Putin government exhibits the following patterns:

- Security – The Putin government mentions security concerns more than any other polity; this is related to their engagement in conflicts in the region and to the pervasive threat they perceive the US and NATO to be.

- Economic Factors – The Putin government has one of the highest densities for economic factors indicating that economic interests are a key factor in their decision calculus.

- Domestic Constraints – The Putin government seldom mentions domestic issues.

- Prestige – The Putin government ranks among the lowest of all the polities for the density of prestige-related themes. This is consistent with thematic analysis of the importance of emotive language. Compared to other polities, the Putin government exhibits a cool, measured rhetoric in discussing regional security concerns. This could be a form of deception or evidence of a patient approach to political developments in the region.

Question (QL2): What are the strategic and operational implications of the Turkish Army’s recent intervention in northern Syria for the coalition campaign plan to defeat ISIL? What is the impact of this intervention on the viability of coalition vetted indigenous ground forces, Syrian Defense Forces and Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (formerly ANF)?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

There is general consensus among the expert contributors that the strategic and operational implications of the Turkish incursion are minimal: each sees the incursion as consistent with previous Turkish policy and long-standing interests. Turkey’s activities should be viewed through the lens of its core strategic interest in removing the threat of Kurdish separatism, which at present has been exacerbated by renewed Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) insurgency inside Turkey, its influence in northern Iraq, and the expansion of Kurdish territories in Syria more generally. As one commented, Turkey will prioritize itself. This means preventing the strengthening of Kurds at all costs (including indirect support to those fighting them). It also means patrolling borders, harsh treatment of those who try to get through and/or corrupt practices such as involvement in smuggling. One implication of note however is the increased risk of escalation between Turkey and Russia and Turkey and the US-backed Peoples Protection Units (YPG) that the incursion poses.

Establishing a Turkish zone of influence in northern Syria accommodates multiple Turkish interests simultaneously: from the point of view of the leadership, it should increase domestic support for President Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP); it should allow Turkey to gain control of costly and potentially disruptive refugee flows into Turkey and reduce the threat of ISIL or PKK activities in Turkey; it prohibits establishment of a unified Kurdish territory in northern Syria; and, it secures Turkey’s seat at the table in any Syrian settlement. In addition, a Turkish-controlled zone could establish a staging area from which Syrian Opposition forces could check PYD expansionism, secure the Aleppo corridor and clear ISIL from Turkey’s borders.

In terms of the impact of the intervention on the viability of coalition-vetted ground forces, Alexis Everington (MSI) argues that in order for the campaign against ISIL to succeed in Syria two conditions must be met: 1) that opposition forces in Syria believe that the effort to defeat ISIL goes hand-in-hand with defeat of the Assad regime; and 2) that there are moderate, “victorious” local Sunni opposition fighters that mainstream society can support. If not, the general population is likely to support more extreme alternatives (like Jabhat Fatah al-Sham) simply for lack of viable Sunni alternatives.1 Hamit Bozarslan (EHESS) suggests that unfortunately the ship may have sailed on this condition. He argues that the Free Syrian Army of today, that Turkey backs, has little resemblance to the Free Syrian Army of 2011: many of its components hate the US, are close to radical jihadis and most importantly, in his view are a very weak fighting force. He explains that they succeeded recently in Jarablus because ISIL did not fight (organizing a suicide-attack and destroying four Turkish tanks, simply showed that ISIL could retaliate).

Finally, Bernard Carreau (NDU) argues that “the U.S. should welcome the Turkish incursion into northern Syria and could do so most effectively by reducing its support of the SDF and YPG.” Doing so he believes could make Turkey “the most valuable U.S. ally in Syria and Iraq.” Additionally, the experts suggest that it is important to remember that the Turkish leadership has seen and will continue to see the fight against ISIL through the lens of its impact on Kurdish separatism and terrorism inside Turkey including Kurdish consolidation of power along the Syrian border. The impact on Opposition forces depends on the degree to which they see that the Turkish moves, as well as the campaign against ISIL address their objective of toppling the Assad regime.

Contributing Authors

Natali, D. (National Defense University), Cagaptay, S. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Everington, A. (Madison-Springfield, Inc.), Carreau, B. (National Defense University),Bozarslan, H.(Ecole des Hautes Estudes en Sciences Sociales), Aguero, S. (US Army), Hoffman, M. (Center for American Progress), Sayigh, Y. (Carnegie Middle East Center)

Defense Science Board 60th Anniversary

On September 20, 2016, the Defense Science Board celebrated its 60th anniversary with an all-day event in Washington DC focused on a variety of topics from a host of speakers and panelists. Dr. Popp took part on a panel focused on Artificial Intelligence (AI): What’s Real, What’s not and is this the DoD Third Offset?

The panel was moderated by the honorable Zachary Lemnios of IBM, and the other panelists included: Dr. Manuela Veloso from CMU, Dr. Bill Mark from SRI International, and Dr. David Kenny from IBM Watson. The agenda for the event can be found here.

DSB Agenda

As background for the panel, the Department of Defense has made significant investments over the past 50 years, in what many regard as three waves of Artificial Intelligence. The first wave (1950-1970) launched the academic field of computer science, opened an era of discovery and set the foundation for signal processing, computer vision, computer speech and language understanding. The second wave (1970-1990) saw codification of knowledge in expert systems, using rule bases, and beginnings of simple machine inference to do reasoning (think things like computer chess), along with exploration of computer architectures, specialized for AI applications. The third wave (1990- present) launched the era of large scale robotics, including autonomous machines, along with real breakthroughs in the use of neural network architectures, inspired by better understanding of how the brain works. The panel focus was to shed light on how Artificial Intelligence has been adopted in the commercial sector, what new value and impact has resulted, the key remaining technical barriers to adopting AI in the defense sector and how AI could be positioned for an enduring strategic national security advantage.

Dr. Popp’s remarks addressed AI from an “analytic intelligence” perspective to help clients understand people and their behaviors on critical, complex decision-making problems. He discussed the importance of utilizing various analytic methods (including qualitative, quantitative, and mix-method approaches) and multidisciplinary social science techniques (from economics, political science, anthropology, sociology, psychology, social psychology, etc) to help clients address the complexity, ambiguity and uncertainty inherent in understanding people and their behaviors. He indicated the objective for analytic intelligence is to help clients make more informed and better decisions in understanding people and their behaviors by providing them with deeper analyses and clarifying insights.

He also discussed five critical barriers to adopting this type of technology, namely, automated coding – using automated methods to code largely text-based data into “soft” metrics for analysis such as respect, honor, dignity, intent, grievance, motivation, influence, and perceptions; machine translation – a lot of data germane for human behavior problems in the social sciences are in foreign languages, and important meaning can oftentimes get lost in the translation; analytic integration – integrating multiple results and findings representing multiple academic and professional disciplines and analytic approaches into a comprehensive and robust analysis relevant to the operational community or decision-maker; effective presentation – distilling highly technical information and presenting it with parsimony and precision in a manner that is accessible and useful to a broad community of interest; and augmented intelligence – machines replicating the critical thinking and analytic reasoning skills and experiences that humans have.

Everything is Gray: Iran’s Approach to Shaping and Influence Operations.

Speaker: Eisenstadt, M. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy).

Date: October 2016.

Michael Eisenstadt is Kahn Fellow, and director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. A specialist in Persian Gulf and Arab-Israeli security affairs, he has published widely on irregular and conventional warfare and nuclear weapons proliferation in the Middle East. His most recent publications include: Missiles in Iran’s Military Doctrine and Strategy (forthcoming); Iran’s Lengthening Cyber Shadow (Washington Institute, 2016); The Strategic Culture of the Islamic Republic of Iran: Religion, Expediency, and Soft Power in an Era of Disruptive Change (Marine Corps University: 2015); Deterring an Iranian Nuclear Breakout (Washington Institute, 2015); Defeating ISIS: A Strategy for a Resilient Adversary and an Intractable Conflict (Washington Institute, 2014); An Enhanced Train-and-Equip Program for the Moderate Syrian Opposition: A Key Element of U.S. Policy Toward Syria and Iraq (with Jeffrey White, the Washington Institute, 2014); What Iran’s Chemical Past Tells Us About its Nuclear Future (Washington Institute, 2014); Beyond Worst Case Analysis: Iran’s Likely Responses to an Israeli Preventive Strike (with Michael Knights, The Washington Institute, 2012), and; Iran’s Influence in Iraq: Countering Tehran’s Whole-of-Government Approach (with Michael Knights and Ahmed Ali, The Washington Institute, 2011). Prior to joining the Institute in 1989, Mr. Eisenstadt worked as a military analyst with the U.S. government. Mr. Eisenstadt served for twenty-six years as an officer in the U.S. Army Reserve before retiring in 2010. His military service included stints in Iraq; Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan; Turkey; the Office of the Secretary of Defense; the Joint Staff, and; U.S. Central Command headquarters. In 1992, he took a leave of absence from the Institute to work on the U.S. Air Force Gulf War Air Power Survey. Mr. Eisenstadt earned an MA in Arab Studies from Georgetown University and has traveled widely in the Middle East.