NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

The Science of Decision Making Across the Span of Human Activity.

Author | Editor: Wright, N. (University of Birmingham & Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) & Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc).

The US is affected by the decisions of highly diverse actors, ranging from individuals, to groups (e.g. Violent Extremist Organizations; VEOs) to large and sophisticated states. The behavior of actors at any of these levels can seem “irrational” or “incomprehensible” and thus difficult to deter or influence. Understanding seemingly incomprehensible decision making is even more crucial given the growing centrality of hybrid warfare to the challenges US planners face.

Decisions are made in context and, except for the most extreme (either dire or trivial), they bear on the multiple concerns, preferences and interests a decision maker may have. The choice problems that prompt decisions are comprised of three elements: 1) the options for action an actor believes he/she has; 2) the dimensions (concerns, interests) that determine his preferences over those options; and 3) what he believes other relevant actors will do (i.e., the options and preferences attributed to others, in some cases including the state of nature.) The range of outcomes and actor expected is determined by combining his own options with what he expects others to do. In general, the difference between decision models based on strict rationality assumptions (i.e., rational choice, game theoretic approaches, expected utilty/cost benefit analyses) and those that relax or eliminate these assumptions lies in their suppositions about the nature of the processes by which multi- dimension choice problems are solved and the factors that impinge upon those processes.

Decision Making and Deterrence

Deterring unfavorable actions either by an adversary or a friend is an issue of perception; it has to do with our ability to influence how others construct their choice problems. From a decision-making perspective then, successful deterrence requires the power to alter another’s perception of the demands associated with achieving his objectives to the degree that he chooses to forego actions he would otherwise take. It is important to note that even decision approaches that include “non-rational” factors such as a decision maker’s affective state, health problems, or fatigue, still rely on assumptions about basic human or group behavior. Namely, that their actions are purposeful and that people seek to avoid self-injury or harm however they may define it. Grasping a potential adversary’s understanding of what is injurious or harmful, the interests that impinge on a choice of action, the constraints imbedded in that choice problem, and the process by which it is solved are the critical information requirements for planning to deter terror attacks, regional conflict, nuclear proliferation and even weaponization of space.

US planners and decision makers will require sophisticated analyses related to each of these factors to evaluate how deterrence messages and signals are likely to be received by adversaries and even which alternative, less unfavorable adversary behaviors might be encouraged. They will need the same types of understanding regarding ally decision making in order to send the most effective messages regarding US resolve to extend our deterrent capabilities to their shores.

A final note involves something very often overlooked in US deterrence planning: understanding the political, bureaucratic and social preferences and obligations that condition our own choice problems and decisions. This helps us better appreciate and plan against those circumstances in which we may be self-deterred, and when our own choice processes pose barriers to effective implementation of deterrence messaging or actions.

The Science of Decision Making across the Span of Human Activity

The types of hybrid conflicts that appear to have become the “new normal” in global affairs require equally hybrid response including deterring decisions being made by individuals, groups and states operating simultaneously (e.g. in Ukraine) in various parts of the globe. Taken together the chapters that comprise this volume describe how seemingly incomprehensible decisions made at different levels of analysis most often arise from the predictable ways that individuals, groups and states function. This is a first step in generating the sophisticated understanding of deterrence decisions.

In Chapter 1 Nick Wright draws from neuroscience research to explain adversary behaviors in terms of brain functions and behavioral responses. This predicts different responses to threats intended to deter adversaries versus threats intended to compel other behaviors – and when identical threats provoke attack. He also points out how easy it is to misinterpret an adversary’s activities and response to our own activities simply by our failure to consider the impacts of perceived unfairness.

In Chapter 2 Peter Suedfeld describes the conceptual progress of less dynamic to more dynamic decision theories and models. He presents his cognitive managerial model to help explain how cognitive factors and decision processing at the individual level are conditioned by the nature of the circumstance that the decision maker finds himself at the time of decision.

Clark McCauley moves the discussion to the level of group decision making in Chapter 3. He explains why group decisions are more than just the sum of individual choices. He presents an evolved group dynamics theory to explain how the type of attractiveness that defines the group can result in either: hyper consensual and often premature choice (groupthink); or can polarize the group beyond where its individuals members would have gone alone (e.g. with implications for radicalization).

In Chapter 4 David Gompert, Hans Binnendijk and Bonny Lin discuss twelve cases of war and peace decision making by national leaders and the role that the leaders’ cognitive models and personality traits play in marking the difference between what have been seen as state-level blunders and national security successes.

In Chapter 5 Gina Ligon and Douglas Derrick point out that there are decision dimensions included in VEO decision making that are unique to those types of organizations, including for example, the need for increasing violence both for reasons of organizational credibility and to maintain public attention. VEO decisions can appear to be incomprehensible or unpredictable if we consider violence as a VEO decision variable or concern rather than just a tactic.

In Chapter 6 Timothy Heath and Cortez Cooper provide an analysis of Chinese national security decision making, and in the final chapter Ed Robbins and Hunter Hustus provide the practitioners view of the value of deterrence over compellence in achieving US national security goals.

In addition to their individual contributions, two broader themes emerge when the chapters in this white paper are taken together:

- Internal Structures Condition Decisions and Behavior at all Levels of Analysis. Observable decisions are often the result of competition and interaction between internal systems, beliefs, interests, factions, components or bureaucracies. Even if not the intention, seemingly inconsistent or even self-defeating behaviors and decisions can arise even from normal functioning of these internal components as internal struggles play out in different contexts. This is true at the level of the individual decision maker where different systems in the brain constitute those structures; at the group level where the attractiveness or source of cohesion and the form of interdependence among group members significantly impact group norms and decision; and at the organization level where internal structures such as bureaucracies can incentivize certain choices and make decisions and actions inconsistent.

- Especially in Ambiguous Operating Environments the Analysis of Adversary Decision Making must be Multi-level. Decision making has common features across levels as well as features specific to the each level. As the categorical boundaries between forms of conflict are increasingly replaced by ambiguous operating environments, the best insight into an adversary’s behavior will require study of decision process and contextual factors on multiple levels of analysis (e.g., individual leader integrative complexity within the context of the structure and norms of his decision group and the bureaucratic pressures of his organization).

Contributing Authors

Maj Gen (Sel) Tim Fay (USAF/A3-5), Dr. Allison AstorinoCourtois (NSI), Mr. Cortez Cooper (RAND), Dr. Douglas C. Derrick (University Nebraska Omaha), Mr. Timothy Heath (RAND), Mr. Hunter Hustus (AF/A10), Dr. Gina Ligon (University Nebraska Omaha), Dr. Bonny Lin (RAND), Dr. Clark McCauley (Bryn Mawr College), Dr. Edward Robbins (AF/A10), Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Dr. Nicholas D. Wright (Carnegie)

Stability Model Users' Guide: Incorporating StaM Analysis of Nigeria for Illustration.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., Brickman, D., Desjardins, A., Popp, G. & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc).

Over the past decade the United States Government has recognized the importance of obtaining a rich contextual understanding of the operating environment, specifically focusing on the human terrain element, when addressing the current threats facing United States security interests, at home and abroad. This emphasis reflects a desire to obtain insight into the motivations underlying others’ intended or actual participation in violence against the United States, as well as the engagement strategies and initiatives that would be effective and sustainable within a given area of interest (AOI). However, this shift in thinking requires analysts and planners to quickly develop a nuanced understanding of the AOIs in which they are working in order to systematically assess their overall stability and identify areas of strength and weakness. A holistic understanding of the operating environment makes it possible to identify critical points in the system – both for stability and instability – and target engagement strategies and initiatives accordingly. This assessment also examines not only the first-order effects, but also potential second- and third-order effects, of US actions across multiple dimensions (governing, economic, and social).,

StaM Overview

NSI’s Stability Model (StaM) represents both a conceptual framework and an analytic methodology to guide users through a systematic process of obtaining a rich contextual understanding of the operating environment. The StaM aids users not only in identifying the factors that explain the stability or instability of a nationTstate, region, or other area of interest, but also in making the connections between and among the various stability factors apparent—allowing users to derive all implications of a potential engagement strategy. The StaM methodology involves an iterative process of “tailoring” or customizing the generic framework to a specific geographic or political area of interest. The output of a StaM effort includes identification of immediate and longerTterm buffers to political, economic, and social stability and sources of population resilience, as well as immediate and longerTterm drivers of instability and collapse. Once a tailored StaM has been prepared, it can be used to address further questions; these include questions regarding the impact of external actors or the most effective and stabilityTpromoting means of engaging with the AOI., , The generic StaM framework consolidates political, economic, and social peer-reviewed quantitative and qualitative scholarship into a single stability model based on these three dimensions, and, critically, specifies the relationships among them. As such, the StaM represents a cross-dimension summary, which draws on rich traditions of theory and research on stability and instability from diverse fields, including anthropology, political science and international relations, social psychology, sociology, and economics. Five key assumptions, shown in Table 1 below, serve as the foundation of the generic StaM.

StaM Assumptions

- A1: Political, economic, and social stability are necessary, but not sufficient, to explain or predict the durability (overall stability) of a political system.

- A2: A governing system will be stable if it is perceived by its constituents to meet their needs (i.e., provides material or nonBmaterial “goods”) and expectations.

- A3: Constituent needs and expectations are culturally and contextually dependent and adaptive.

- A4: The primary “goods” expected from a governing authority are the provision of internal order and external security sufficient for people to meet their physical and psychological needs.

- A5: People do not seek to change systems from which they benefit. Dissatisfaction with the provision of goods by a governing authority reduces the perceived legitimacy of and encourages opposition to that entity.

The overall stability of an AOI—which can be defined within the StaM as either a nation-state, sub-state region, or city—is defined as a compound function of its political, economic, and social stability. Note that the StaM is agnostic to form of governance. Democratic governance is not presumed. It is also agnostic to the type of economic system, and typically will include formal, grey (or informal), and black economic elements. Finally, within the StaM, neither overall stability nor social stability suggest violence- or unrest-free societies, but those where social structures are known and durable, and social cleavages and conflicts are for the most part manageable. Furthermore, stability does not imply a lack of change. Rather, it denotes the flexibility and resilience of a system to adapt to changes over time, without economic, social, or political consequences that threaten the viability of the system.

Analytic Uses of the StaM

Identifying AOI-specific stability conditions

A fully tailored StaM provides analysts and planners with a holistic picture of the governing, economic and social conditions within a specific AOI, and whether that AOI is moving toward or away from conditions consistent with stability in both the short and longer term. It also enables the identification of AOI-specific drivers of instability, buffers to stability and the exogenous conditions that can intensify these effects. Tailoring a StaM requires systematically considering all of the central concepts theory and research have shown effect stability; following the model process allows the planner or analyst confidence that significant current or future sources of stability or instability have not been overlooked.

Monitoring and early warning

Once a tailored StaM has been created for an AOI, and the drivers, buffers and intensifiers identified, the analyst or planner effectively understands what components of the model to pay attention to. This can significantly decrease the time and data requirements for monitoring an AOI over time. Furthermore, as the StaM also maps the crosscutting effects model components have on each other, we can monitor how changes in other components of the model may influence the condition of individual drivers and buffers. This increases the probability that changes with the potential to significantly increase or decrease stability will be identified early in their development.

Assessing the second and third order effects of engagement activities

One of the strengths of the StaM as an analytic tool is its ability to map the interrelationships between model components (crosscutting effects). This makes it possible for analysts and planners to trace the possible consequences of a proposed action and identify possible unintended consequences prior to undertaking an engagement activity. In effect, the model allows users to gain the “lessons learned” without having to make the mistakes that teach the lesson. More importantly, perhaps, the model enables planners and analysts to identify the location and causes of those negative effects. If identified in advance it is possible that such obstacles can be avoided and unintended consequences minimized.

Maximizing the effectiveness of engagement activities

The same crosscutting effects in the StaM that enable the identification of unintended consequences can also be used to determine how engagement activities can be structured and positioned to maximize their effect. By tracing the crosscutting effects from the component that is directly influenced by an engagement action, the planner or analyst can determine the system-wide implications of a specifically targeted action. By comparing different points or methods of influence, the relative impact of various COAs can be compared. In effect, you can determine where you get the most “bang for your buck”.

Improving coordination across USG agencies and international partners

In many cases more than one USG agency may be operating in an AOI, this creates opportunities for coordination, but also risks of duplication or even counteraction of effort. By assessing the second and third order effects of all USG efforts in a particular AOI, the planner or analyst can identify the areas where coordination of effort is most critical. Such an assessment can also bring to light opportunities where interagency collaboration allow individual agencies to achieve mission objectives in areas that they cannot influence effectively working alone. This also holds for working with international partners.

Assessing the implications of external actor actions

It can often be the case that the U.S. is operating in an AOI in which other external actors – either states or non-state actors – are present. The actions of these external actors have potential to impact the stability of the AOI. The StaM allows analysts and planners to map the effects of specific external actor actions (e.g.: presence of VEOs, large-scale economic investment by a foreign power) on the stability of the system as a whole. This in turn can provide a fuller picture of the possible implications of those actions for U.S. interests broadly, and ongoing or planned engagement activities more specifically.

Assessing the second and third order effects of shocks to the system

An AOI-tailored StaM can also be used to assess the likely indirect effects of a particular system shock or crisis event (e.g.: natural disaster, global financial crisis, major terrorist attack). The immediate effects of the shock (for example displacement of populations, crop destruction and infrastructure damage after a natural disaster) can be located on the StaM and then their second and third order effects mapped across the model. Identification of these effects prior to a shock occurring can improve planning and response.

Multi-Method Assessment of ISIL in Support of SOCCENT: Subject Matter Expert Elicitation Summary Report, July – November 2014.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Rieger, T. (NSI, Inc).

From July through November 2014, NSI conducted a Subject Matter Expert (SME) Elicitation study to gather insights from interviews, panel discussions, seminars, and personal communications with over 50 SMEs from the United States, the Middle East, and Europe. The interview questionnaire and transcripts from the SME elicitation effort are available upon request. CTTSO provided the Apptek Talk2Me platform to expedite the transcription of the SME Elicitation interviews. In addition, all of the data (human edited and original audio) are posted on the Web-based Talk2Me platform for the SMA study for further analytics and reporting.

This report summarizes SME findings that help us understand ISIL’s intangible appeal. However, it does not attempt to adjudicate or force convergence of the findings.

Conditions: The Perfect Storm

Some SMEs described conditions on the ground as a “perfect storm” for the emergence of ISIL. The confluence of the conditions listed below allowed ISIL to rise rapidly.

- Failed states of Iraq and Syria: The power vacuum in the Sunni regions of Iraq and Syria opened the door for an alternative governing force to coalesce and gain the acquiescence and/or support of the civilian 3 population.

- Sunni grievances: The combination of political exclusion of Sunnis from government in Iraq and Syria along with the abuses visited upon Syrian Sunnis by the Assad regime have fed narratives of Sunni grievance, victimization, and marginalization.

- Arab world undergoing rapid change: ISIL is an expression of rising Islamist fundamentalism, declining sense of state-based nationalism, and a sense of empowerment spurred by the Arab Spring.

- Information Age: The advent of the information age makes it easier for people to communicate across large distances, to create a platform for sharing experiences and beliefs with like-minded individuals, and to actively persuade others to sympathize with or join a cause.

- Youth bulge: Like many parts of the developing world, Syria and Iraq are experiencing a youth bulge that, when combined with unemployment and lack of political voice, has resulted in a reservoir of young, angry men.

On the whole, SMEs felt that these conditions made it possible for ISIL to seize the opportunity to push for an alternative form of governance in the region. However, while these conditions were extremely important, ISIL’s sustainability and longevity is also based on its capacity to control the population and to garner sympathy and support from the broader Sunni Muslim population both inside and outside the region.

Capacity to Control

SMEs believed that ISIL’s capacity to control is based on several factors.

- Fear and coercion: ISIL has a monopoly over the use of force in areas it “governs.” It uses the implicit and explicit threat of violence against civilians to ensure acquiescence.

- Provision of better governance and order: Some argue that ISIL provides better governance and essential services than what was experienced under Iraqi and Syrian rule. Furthermore, ISIL provides some degree of stability and order in a previously uncertain environment.

- Lack of a viable alternative: There are currently no alternative forms of Sunni-empowered governance available. ISIL draws on the power of collective Sunni identity and Sunni grievances to establish its legitimacy.

- Strong leadership: ISIL has a strong, agile, pragmatic leadership and organizational structure. It has a highly motivated and a dedicated rank and file under the leadership of a disciplined and experienced cadre, supported by consistent and compelling messaging.

- Success breeds success: ISIL’s momentum and its ability to survive coalition attacks to date plays a role in convincing civilians and local power brokers that it will be around for the long-term, which reinforces support or acquiescence to ISIL, and in turn further reinforces ISIL’s capacity to control.

ISIL’s capacity to control is largely based on its interactions with the local population. However, ISIL also enjoys sympathy, support, and recruits from the global Sunni Muslim population. SMEs interviewed felt that the primary way ISIL achieves support from the global Sunni Muslim population is through persuasive use of narrative. SMEs identified over 20 narratives ISIL uses to persuade, the most powerful of which are described below.

Persuasive Narratives

Narratives are messages that represent the ideals, beliefs, and social constructs of a group. ISIL uses them within the civilian population to consolidate control and amongst the global Sunni Muslim population to garner sympathy, support, and recruits.

- Moral imperative: ISIL uses a variety of narratives to convey the idea that Muslims have a moral imperative to support them. These narratives include the restitution of the caliphate, creation of a utopian society based on Muslim laws and values, ISIL as a representative of the pure form of Islam, ISIL bringing back the Golden Age of Islam, al Baghdadi as a direct descendent of the Prophet, and that ISIL’s caliphate will unite all Sunni Muslims.

- Sunni grievances and victimhood: ISIL uses shared feelings of marginalization, repression, and lack of power to gain legitimacy and support. They draw on sub-narratives of victimization among Sunnis at the hands of Shias and the West to cement this powerful narrative.

- Immediacy: ISIL rejects al Qaeda’s core narrative that it needed to wait for the right time to establish a caliphate. ISIL claims that they did it within months. ISIL touts its willingness to take action, combined with its success in establishing what it calls a caliphate, as evidence of their proclaimed righteousness and destiny.

- Reinvention of self: No matter what kind of life you led, when you convert to Islam and join the fight, all previous wrongdoing is washed away. ISIL offers a new start and a new sense of identity and purpose to anyone who joins them.

- Thrills, adventures, and heroism: Some individuals are particularly drawn to ISIL because it advertises thrills, adventures, and opportunities for heroism (and violence) that appeal to some young men’s sense of masculinity.

Schools of Thought

While these factors represent areas of qualified agreement on key factors explaining ISIL support, SMEs differed on which factors were the most important, which led to two primary schools of thought regarding ISIL’s longevity.

- The first school of thought is ISIL has resilient properties via its capacity to control people and territory stemming from pragmatic leadership and organization, intimidation tactics, tapping into existing Sunni grievances and use of a well-developed narrative and media outreach to attract and motivate fighters.

- The second school of thought is ISIL is not a durable organization. It has taken advantage of a pre-existing sectarian conflict to acquire land, wealth, and power. It only attracts a narrow band of disaffected Sunni youth, is alienating local populations by over-the-top violence and harsh implementation of Sharia, is unable to expand into territories controlled by functioning states, and does not possess the expertise required to form a bureaucracy and effectively govern.

In reviewing the effort, a third school of thought emerged: that the real challenge is not ISIL as an organization, but rather the sense of disempowerment, anger, and frustration in the Muslim world. This condition is evidenced by rising Islamist fundamentalism found within Sunni Muslim populations around the world combined with a declining sense of state-based nationalism. It is fueled by a perception of inequality and thwarted aspirations in addition to the conditions mentioned earlier in this chapter: failed states, demographic shifts, unemployment, drought, spread of communication technologies, marginalization, etc. If the problem is larger than ISIL, then solutions that only seek to undermine ISIL’s capacity to control are insufficient to address the underlying cause of conflict, as they address only the symptoms of the problem and not the underlying root cause.

Additional Factors

This summary presents a cursory review of the many topics addressed by over 50 SMEs interviewed for this effort. In addition, the report also touches on a number of other controversial topics. These include:

- whether ISIL is primarily ideological or opportunistic;

- whether the local elite power base in Iraq and Syria sincerely supports ISIL;

- situational factors contributing to the sustainment of ISIL;

- the degree to which regional Sunni Muslim states support or oppose ISIL; and

- a brief look at whether the rise of other historical violent social movements could be instructive.

SME elicitation through the SMA SOCCENT Speaker Series will continue. To be added to the distribution list for the series, please contact Mr. Sam Rhem at samuel.d.rhem.ctr@mail.mil.

The most recent news on the impact of the National Academy of Sciences’ Deterrence study co-chaired by Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois. The excerpt below is from the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) Report on this year’s National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2016. The HASC has used the National Academy of Sciences’ Deterrence study report to task the Secretary of the Air Force in the Defense Budget.

Strategic Deterrence Research and Education

In the committee report (H. Rept. 113–102) accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014, the committee noted that “challenges remain in educating airmen on their role in safeguarding national security. Educating the warfighters who execute the daily mission of nuclear deterrence remains a critical element to ensuring the level of excellence required for the mission. In the committee report (H. Rept. 113–446) accompanying the Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015, the committee noted that “the [Secretary of Defense] should take appropriate steps to refocus the military member education to ensure it is adequately covering, across-the-board, the essentials of nuclear deterrence policy and operations (including such concepts as strategic stability and escalation control)”.

In addition, the 2014 study by the National Research Council (NRC) titled, “US Air Force Strategic Deterrence Analytic Capabilities,” identified a continued deficiency in the science and research of nuclear deterrence and assurance. The Council found that, “The Air Force, working with its Service partners and the Department of Defense more generally, should pursue research on deterrence and assurance with a coherent approach that involves content analysis, leadership profiling, abstract modeling, and gaming and simulations as a suite of methods. It should organize its investments in analytic and other activities accordingly.” The committee also notes that today’s geopolitical environment presents various threats and opportunities related to nuclear deterrence. With several internal reviews and outside assessments suggesting an increased focus on strategic deterrence education and research programs, and the committee’s multi-year emphasis on this subject, the committee seeks more clarity on the concrete actions taken by the Secretary of the Air Force, as well as future plans, for strengthening nuclear deterrence education and research within the Air Force. Therefore, the committee directs the Secretary of the Air Force to submit a report to the congressional defense committees by March 1, 2016, on the steps taken by various elements of the Air Force to improve service member education on nuclear deterrence and establish a sustainable, coherent, and robust strategic deterrence research program. Such education and research program should include examining the linkages among strategic deterrence and assurance, strategic stability, escalation control, missile defense, strategic conventional capabilities, nuclear terrorism, and nonproliferation efforts. This report should provide an overview of recent actions, as well a multi-year plan, to develop and sustain a research program that addresses the deficiencies identified by the National Research Council and other groups. The committee encourages the Secretary to leverage academia, industry, the other services, and other Government partners to meet the needs of this program.

Interview With Tom Rieger on Overcoming Fear

By Deborah Jeanne Sergeant

After studying dozens of defunct companies both large and small, Tom Rieger found that fear contributed significantly to each company’s demise. Now president of NSI, Inc, he wrote Breaking the Fear Barrier: How Fear Destroys Companies From the Inside Out and What to Do About It (Gallup Press, 2010) to share his discoveries. Home Business Magazine spoke with Rieger about how fear impacts home businesses.

Home Business Magazine (HBM): How does fear affects would-be home entrepreneurs?

Tom Rieger (TR): The fear of losing what you’re holding onto can make you uncomfortable about stepping out of your comfort zone.

HBM: How does fear manifest itself in established home-based businesses?

TR: There are usually three ways in which fear shows up. It’s a pyramid of bureaucracy: parochialism, territorialism, and empire building. Parochialism is when you have an employee or you as a leader tend to view things strictly as a process or through an internal lens, not how your employees or your customers will view things. An assistant may view his job as solely getting you to sign forms you need without seeing it’s taking time away from business. It’s an employee that defines his world by the piece, not the puzzle.

Territorialism is when you have someone in your business who is exerting excessive control over budget, information, or other employees. That comes out of fear of loss of that control. Empire building is the last one. A home business is less subject to this. When you have a part of an organization that feels their “empire” is threatened, invariably you’ll have conflict. Empire building means open warfare within an organization. It’s a fear of losing self-sufficiency. It’s a fear of losing decision rights. Once I feel I own something, it increases in value to me, but only to me.

HBM: Is the goal to eliminate or manage fear, and how does one do it?

TR: Not all fear is bad. People need some pressure to perform. Fear that is focused on the wrong thing: That’s bad. Remove all the barriers. Try to understand what people are focusing on. Have they lost sight of the mission? The mission is the ultimate arbiter of every decision. Make sure the rules and policies are doing what you want without collateral damage. There are four types of rules: gospel, ghost, ground rules, and guidelines. “Gospel” rules are absolute rules you must follow. If people are doing things that don’t make sense but they’re doing them because that’s the way they’ve always been done, that’s the “ghost.” They aren’t rules that are really rules. “Guidelines” are flexible rules. “Ground rules” are when you make a judgment call, but don’t go out of bounds.

HBM: Many home entrepreneurs have worked in a traditional setting, and to form a virtual remote team may seem a fearful thing. What can home entrepreneurs do to feel more comfortable?

TR: Understand the world your virtual team lives in. Communication is essential; over communicate almost. Regularly have some face-to-face time, and make absolutely sure that you have transparency on sharing information. It takes a lot more work to keep information flowing and to keep it shared. It takes more collaboration to keep it going when you’re scattered across the country.

HBM: How can fear of failure effect entrepreneurs’ day-to-day actions, and what can they do to overcome it?

TR: People will do things to prevent the loss even if it means they’re also preventing the gain. They erect walls to keep form stepping off the cliff even if it prevents them from going forward. They hold onto processes, technology, and methods that are outdated. Don’t let your fear keep you from succeeding.

HBM: Some home entrepreneurs fear success. Why?

TR: Success means change, and change is different. It means you’ll have to give up something, and losing something is fearful. The business you have five years from now may be completely different than the one you have now. Maybe some of the sacred practices that drove you up to $1 million won’t be adequate to get you to $5 million. Develop a set of guiding principles to help you avoid risk, help customers, and operate better. You can step back and say, “Will this help or should I stick with what I have?” Don’t be afraid to evolve.

HBM: Rieger has operated a worldwide customer measurement program for a Fortune 100 company. Rieger and his wife of 17 years have a 13-year-old son and live in California. Visit http://nsiteam.com/

Executive Order — Using Behavioral Science Insights to Better Serve the American People

By Robert Popp

Where Federal policies have been designed to reflect behavioral science insights, they have substantially improved outcomes for the individuals, families, communities, and businesses those policies serve. – President Barack Obama, 2015

On September 15, 2015 President Barack Obama released the Executive Order, Using Behavioral Science Insights to Better Serve the American People. Within this order the President encourages US agencies to develop strategies for applying behavioral science insights to programs and, where possible, rigorously test and evaluate the impact of these insights.

This is a directive that resonates deeply with me and with many of my social scientist colleagues. During the many years I have spent working in and with the US defense establishment I have become acutely aware of the great potential for insights from the wealth of knowledge imbedded in the behavioral and social sciences to enhance US security policy decision-making. I even established a research and analytic firm, NSI, in 2007 to foster and grow just this potential. Nearly a decade later, many scholars and scientists in the social science community have brought their vast experience and collective expertise in the behavioral and social sciences to bear on a wide variety of the most critical national security issues of our time.

During that same time period we have witnessed a mad rush to invest in and embrace the social sciences; on balance this is very good. Regrettably, however, demonstration of the true value and merit of the social sciences among many in the defense and security community has been derailed by ersatz “social scientists” following the money, and a rising skepticism and fatigue among policymakers and practitioners trying to determine how best to meaningfully employ the rigors of behavioral and social science in order to attain mission success. The confluence of these has resulted in a fallout and failure to scrutinize the appropriateness of proposed methods to the problem, which among other errors, shortchanges validation and stymies the effort to improve critically important predictive abilities in the behavioral and social sciences. So, when I saw the President’s Executive Order I was extremely heartened to find that the unique value of behavioral and social science to enhance US security policy decision-making is valued and appreciated at the highest levels of the US government.

Many social scientists that have supported the defense and security community live by and embody the ethos of this executive order. They recognized in the aftermath of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that all too often the human side of the operational environment was not being fully considered in the analytical and decision-making process. To address this shortfall, social scientists — anthropologists, political scientists, economists, psychologists, sociologists, and linguists – many of whom are also rigorously trained in the scientific method and analytical approaches, offer a rich resource for military commanders and decision-makers to tap. Their wisdom and expertise across the social science disciplines can provide precisely the deep insights into the subtleties of human behavior across location, culture and context that are critically needed to improve decision-making outcomes and effectiveness.

For nearly a decade, they have been helping senior decision-makers, military commanders, and agencies within the national security apparatus navigate their most complex and difficult analytical challenges using the exact types of behavioral science insights that the President is calling for. Some examples consistent with the call for action by the President include applying nation state stability models to identify the political, economic and social drivers of instability and conflict within such diverse areas as Nigeria, Pakistan, the West Bank and Afghanistan; using neurocognitive social psychological constructs to study radicalization of populations and violent extremist organizations; conducting mix-method multi-disciplinary analyses to assess near- and long-term influence of ISIL in Iraq, Syria and the Middle East region as a whole; and applying discourse methods rooted in linguistics to understand the significance and inconsistencies in leader speeches and social media data during the civil uprising in the Arab Spring.

In these examples, the insights due to the behavioral and social sciences enabled a stronger foundation for better decision-making, improved understanding of unfamiliar environments, discovered and avoided unintentional consequences, and determined the implications of different futures.

I am deeply encouraged by the directive of this Executive Order and urge policymakers and practitioners within the defense and security community to utilize the proven methods in the behavioral and social sciences to improve their decision-making outcomes and effectiveness, and ultimately mission success.

Dr. Lawrence A. Kuznar is professor of anthropology at IPFW and has advised the US Department of Defense on global terrorism. He wrote this for The Journal Gazette on November 25, 2015.

I have been part of a team of academic and government researchers who, for nearly two years, have been analyzing the rise of the so-called “Islamic State” – ISIS or Daesh, as most of its opponents prefer to call them. We have worked with military personnel to provide a realistic understanding of the threat Daesh presents to us, as well as the best way to counter the threat.

Turkey shot down a Russian fighter Tuesday, potentially bringing NATO and the US into war with Russia. Daesh consciously and patiently created the conditions for this to happen, all to further their apocalyptic cause. Thoughtless reactions to this event only help to advance Daesh’s goal.

Pronouncements to “knock the hell out of,” “bomb the s–t out of,” “take the oil from,” or “strangulate” ISIS are easy to make. However, the reality is not only far more complicated and difficult, but also far more dangerous, and not because of anything ISIS would do to us. It is from what the enemies of Daesh will do to one another.

Daesh is faithfully following a strategy of sowing discord among its more powerful enemies to weaken them and create chaos. Chaos opens an opportunity for Daesh to provide order and recruit disoriented and disillusioned victims. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (killed in 2006) founded the original organization that would eventually become Daesh. He first conceived of this strategy for attacking Shia Muslims back in 1998. A Jihadist strategic manual, The Management of Savagery,” codified the basic elements of this strategy and Daesh, even more than al Qaeda, has put it into practice.

A year ago those of us who argued that Daesh’s strategic goal was to strike the West and create the conditions for their perceived Armageddon were called alarmists. Now, it appears to be accepted as fact. Daesh has explicitly stated that its goal is to bring local factions and major Western powers to the Turkish border near a small Syrian town called Dabiq, their purported location for the final Apocalypse.

Western powers have played directly into their plans. Daesh has successfully brought Western powers, antagonistic to one another (NATO allies and Russia), into close proximity. Tuesday, Turkey (a NATO member) shot down a Russian fighter that, by my rough approximation from a Google map, was less than 15 miles from Dabiq. Are we trying to make Daesh a success? If Turkey invokes Article 5 of NATO, Daesh could potentially get exactly what it wants – World War III.

A day before the Paris attacks, Daesh released perhaps its most technologically sophisticated and most graphic propaganda video yet, entitled, “Soon, Very Soon the Blood Will Spill Like an Ocean,” in which it directly threatened Moscow. And the onslaught against the West ensued.

Daesh has been a genuine threat to the West, our allies and our homeland. Its warriors must be fought; make no mistake that a war has been on for awhile. However, if we fight this war thoughtlessly, we play into Daesh’s hands, just like all of their more powerful local adversaries (the Syrian regime, Hezbollah, al Qaida, the Free Syrian Army, the Sunni tribes, the government of Iraq, Shia militias in Iraq, Iran, Kurdish factions in Iraq andSyria). Daesh should never have gotten this far, but its strategy has served it well, and now it has knowingly sowed discord among Western powers.

The latest issue of Daesh’s online magazine, ominously entitled Dabiq, contains the article, “You Think They Are Together but Their Hearts are Divided” that ends, “May Allah continue to break and shatter the ranks of the kafir (infidel – that means us) coalitions and alliances all over the earth.”

Western powers must unite and Americans must support longer-term strategies to combat jihadist threats that would include diplomatic, informational and local as well as military means. Simply crushing Daesh militarily is tantamount to stepping on a hornet’s nest – the nest is destroyed, but the hornets will scatter and regroup.

Our strategy must be based on support of local forces to degrade and ultimately destroy Daesh and the threat it represents to us, and, frankly, the result will neither be fast nor pretty. We must also plan for the aftermath – the underlying factional conflicts will continue the chaos and likely provide a fertile ground for a Daesh 2.0 to emerge. We need to plan against that as well.

Swaggering pronouncements are easy; real fighting is hard. Are we up to the challenge, or is Daesh right about our weakness? It is time to fight intelligently.

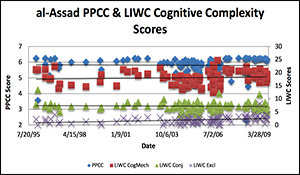

A Multi-disciplinary, Multi-method Approach to Leader Assessment at a Distance: The Case of Bashar al-Assad.

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. (NSI, Inc), Suedfeld, P. (University of British Columbia), Spitaletta, J. (Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Laboratory) & Morrison, B. (University of British Columbia).

This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary discourse analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources.

The results are summarized in a two-part report. Part I (this document) provides a summary, comparison of results, and recommendations. Part II describes each analytical approach in detail.

Data: The speeches used in the study were delivered by al-Assad from Jan 2000 to Sept 2013; the past six years was sampled most densely. Additional Twitter feeds were analyzed to gauge his influence in the region.

Analytical Approaches: Five separate methods analyzed the speeches: (a) automated text analytics that profile al-Assad’s decision making style and ability to appreciate alternative viewpoints; (b) integrative complexity (IC) analysis that reveals al-Assad’s ability to appreciate others’ viewpoints and integrate them into a larger framework; (c) thematic discourse analysis of the cultural and political themes al-Assad expresses before taking action or in reaction to events; (d) qualitative interpretations of major themes in al-Assad’s rhetoric; and (e) analysis of the spread of Twitter feeds. We highlight findings that reinforce each other as particularly robust for policy.

Summary Findings: The major findings of these studies include:

- al-Assad is capable of recognizing other viewpoints and evaluates them in a nuanced and context-dependent manner

- al-Assad values logical argumentation and empirical evidence al-Assad’s integrative complexity is relatively high, but might be lower before he takes decisive action or when under intense threat

- al-Assad’s reasoning is consistent with his Arab nationalist Ba’athist political ideology, and with a consistent opposition to Israel and Western domination; al-Assad sees Arab resistance and his leadership, or at least that of the Ba’ath party, as essential

Main Findings

Basic findings from studies of al-Assad’s speeches, 2000 – 2013

- Various Measures of Cognitive Complexity: Multiple measures converge to show that Assad is capable of appreciating different viewpoints and the nuances between them. al-Assad’s integrative complexity (his ability to differentiate different perspectives and integrate them) is relatively high compared to other leaders in the region. al-Assad furthermore demonstrates an ability to be logically consistent in how he evaluates situations, and is responsive to credible (in his view) empirical evidence.

- Deterrence: Traditional deterrence theory should apply to al-Assad generally, although during periods of intense stress he may deviate more from such a model.

- Integrative Complexity (IC): In general his IC has not changed over the course of the conflict. But analysis of specific events suggests his IC tends to be lower when under intense threat, or before taking decisive and violent action, compared to afterwards.

- Arab Nationalism: al-Assad wants to lead Arab interests; he is a staunch Arab nationalist.

- Opposition to the West and Israel: al-Assad wishes to oppose Western and Israeli influence in the Arab world; the history of Middle Eastern peace talks makes Assad cynical about Israel-Palestine negotiations, despite his cognitive inclination for negotiation. Assad’s narrative of opposing Israel decreases dramatically once Syrian unrest begins (March 2011); return to this narrative may be an indicator of his baseline rhetoric in times of relative peace within Syria.

- Secular Ba’athist Political Ideology: al-Assad’s reasoning and values are consistent with a more secular, Ba’athist, political ideology.

Key Recommendations

We used the doctrinal 7-Step MISO process to characterize al-Assad as a target audience of one, and we absorbed the relevant components of our multi-method analyses into the Target Audience Analysis format. Summary of Key Recommendations along with Supporting Analyses, Part II Location, and Confidence Level are shown in table one. The main practical recommendations are:

- Avoid direct threats to the Syrian Ba’athist regime’s hold on power;

- Appeal to al-Assad’s relatively high baseline level of Cognitive Complexity (ability to see different sides to an issue, flexible decision-making, openness to information), pragmatism, and respect for Arab nationalism to broker a negotiated settlement; and

- Identify and exploit al-Assad’s dynamic levels of Integrative Complexity to assess his relative susceptibility, develop arguments and recommended psychological actions and/or refine assessment criteria at a specific point in time.

A Multi-disciplinary, Multi-method Approach to Leader Assessment at a Distance: The Case of Bashar al-Assad (Part II: Analytic Approaches).

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. (NSI, Inc) & Suedfeld, P. et al. (University of British Columbia).

This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources.

The results are summarized in a two-part report. Part I provides a summary, comparison of results, and recommendations. Part II (this document) describes each analytical approach in detail.

Data: The speeches used in the study were delivered by al-Assad from Jan 2000 to Sept 2013; the past six years was sampled most densely. Additional Twitter feeds were analyzed to gauge his influence in the region.

Analytical Approaches: Five separate methods were used to analyze the speeches:

- Approach 1: Integrative Complexity (IC) analysis as developed by Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia) is a measure of the degree to which a source recognizes more than one aspect of an issue or more than one legitimate viewpoint on it (differentiation), and recognizes relationships among those aspects or viewpoints (integration).

- Approach 2: Thematic Discourse Analysis based on methodologies developed by National Security Innovations, Inc. (NSI) and conducted by Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne (IPFW). It provides general predictions of which themes will precede conflict and which will emerge as a reaction to conflict, an assessment of the major narratives al-Assad draws on to persuade his audiences, and analyses of themes that emerge around specific events.

- Approach 3: Automated Leadership Trait Analysis using ProfilerPlus and the Language Inventory and Word Count (LIWC) software (JHU-APL). The primary objectives were to examine (1) the cognitive complexity through means independent from the UBC method in Approach 1; and (2) al-Assad’s leadership traits using Hermann’s (2002) method of political profiling. Selections of English translations of al-Assad’s speeches were analyzed using two pieces of software: ProfilerPlus; and Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). Automated text analyses ingest and analyze the whole speech not simply randomly selected sections.

- Approach 4: Geopolitical Discourse Development Analysis. CSIS (Center for Strategic and International Studies) analyzed the common corpus of 124 speeches by Bashir al-Assad from 2000 to present. They provided qualitative interpretations of major themes that emerged in al-Assad’s discourse over the course of the 13-year period studied

- Approach 5: Analysis of Influential Arab Twitter Feeds. A team of analysts from Texas A&M University analyzed the twitter feeds of 195 influential Arabs in the Middle East, in each 24 hour period before and after al-Assad delivered a speech for the months of August and September, 2013. They also examined the relative influence of al-Assad and other regional players in the Arabic Twittersphere to determine the extent the regime is able to influence public opinion.

Major Findings: The major findings of these studies include:

- al-Assad is capable of recognizing other viewpoints and evaluates them in a nuanced and context-dependent manner

- al-Assad values logical argumentation and empirical evidence al-Assad’s integrative complexity is relatively high, but might be lower before he takes decisive action or when under intense threat

- al-Assad’s reasoning is consistent with his Arab nationalist Ba’athist political ideology, and with a consistent opposition to Israel and Western domination; al- Assad sees Arab resistance and his leadership, or at least that of the Ba’ath party, as essential.

Key Recommendations: We used the doctrinal 7-Step MISO process to characterize al-Assad as a target audience of one, and we absorbed the relevant components of our multi- method analyses into the Target Audience Analysis format. The main practical recommendations are:

- Avoid direct threats to the Syrian Ba’athist regime’s hold on power;

- Appeal to al-Assad’s relatively high baseline level of Cognitive Complexity (ability to see different sides of an issue, flexible decision-making, openness to information), pragmatism, and respect for Arab nationalism to broker a negotiated settlement; and

- Identify and exploit al-Assad’s dynamic levels of Integrative Complexity to assess his relative susceptibility, develop arguments and recommended psychological actions and/or refine assessment criteria at a specific point in time.

Main Findings

Basic findings from studies of al-Assad’s speeches, 2000 – 2013

- Various Measures of Cognitive Complexity: Multiple measures converge to show that al-Assad is capable of appreciating different viewpoints and the nuances between them. al-Assad’s baseline integrative complexity (his ability to differentiate different perspectives and integrate them) is relatively high compared to other leaders in the region. al-Assad furthermore demonstrates an ability to be logically consistent in how he evaluates situations, and is responsive to credible (in his view) empirical evidence.

- Deterrence: Traditional deterrence theory should apply to al-Assad generally, although during periods of intense stress he may deviate more from such a model.

- Integrative Complexity (IC): In general his IC has not changed over the course of the conflict. But analysis of specific events suggests his IC tends to be lower when he is under intense threat, or before taking decisive and violent action, compared to afterwards.

- Arab Nationalism: al-Assad wants to lead Arab interests; he is a staunch Arab nationalist.

- Opposition to the West and Israel: al-Assad wishes to oppose Western and Israeli influence in the Arab world; the history of Middle Eastern peace talks makes al- Assad cynical about Israel-Palestine negotiations, despite his cognitive inclination for negotiation.

- Secular Ba’athist Political Ideology: al-Assad’s reasoning and values are consistent with a more secular, Ba’athist, political ideology.

Main Recommendations:

We used the doctrinal 7-Step MISO process to characterize al-Assad as a target audience of one, and we absorbed the relevant components of our multi-method analyses into the Target Audience Analysis format. The main practical recommendations are:

- Avoid direct threats to the Syrian Ba’athist regime’s hold on power;

- Appeal to al-Assad’s relatively high baseline level of Cognitive Complexity (ability to see different sides of an issue, flexible decision-making, openness to information), pragmatism, and respect for Arab nationalism to broker a negotiated settlement; and

- Identify and exploit al-Assad’s dynamic levels of Integrative Complexity to assess his relative susceptibility, develop arguments and recommended psychological actions and/or refine assessment criteria at a specific point in time.

Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois was selected to serve on the National Academy of Sciences’ National Security Space Defense and Protection project. The approximate start date for the project is December 15, 2014. The project is sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Office of the Director for National Intelligence. Two reports will be issued: Report 1 will be provided to the sponsors no later than August 15, 2015. Report 2 will be provided to the sponsors no later than December 15, 2015. The project duration is 15 months. Below is the project scope.

Project Scope

The NRC will appoint a study committee to conduct a consensus study in accordance with National Research Council procedures. The committee will first review current, projected, and planned US national security space systems and architecture and receive briefings on known and projected threats to space systems vital to US national security. The committee will then:

- Review the range of options available to address threats to space systems, in terms of deterring hostile actions, defeating hostile actions, and surviving hostile actions.

- Assess potential strategies and plans to counter such threats, including resilience, reconstitution, disaggregation, and other appropriate concepts.

- Assess existing and planned architectures, warfighter requirements, technology development, systems, workforce, or other factors related to addressing such threats.

- Recommend architectures, capabilities and courses of action to address such threats and actions to address affordability, technology risk, and other potential barriers or limiting factors in implementing such courses of action.