NSI Publications

NSI Publications are publications from our professional and technical staff for research efforts sponsored by our government clients (e.g., SMA), conferences, academic journals and other forums.

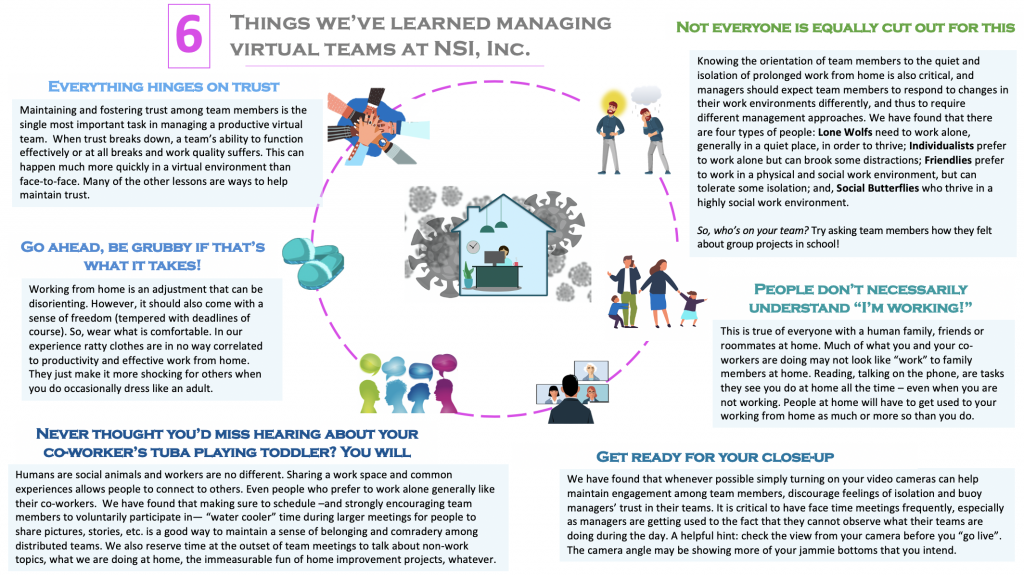

In the era of social distancing and COVID-19, NSI’s Chief Analytic Officer, Dr. Allison Astorino Courtois, details 6 quick insights and lessons from managing NSI’s innovative, virtual workplace for over 13 years. In parallel, NSI’s President, Mr. Tom Rieger, presents NSI/NBI and the Oxford Brain Institute’s strategic partnership to leverage the latest research in psychology, group dynamics, organizational behavior, and neuro-leadership to help provide insight on what helps (and what hurts) the ability of your team to maintain psychological health and resilience. This short video summarizes the work of this partnership.

Please contact TeamHealth@NSIteam.com for more information.

A document elaborating on how NSI has managed its virtual teams is also available for download here.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc.)

Question of Focus

[Q1] What are the primary drivers of internal instability for Iran currently, and how are they responding?

Report Preview

There was consensus among the subject matter experts (SMEs) who responded to this question that the primary driver of internal instability in Iran is the dismal state of the economy. This is consistent with findings from the previous round of ViTTa reports produced for US Central Command.2 This group of SMEs did judge the economic situation in Iran to be more acute than it was six months ago, but do not consider the regime to be in imminent danger of collapse.

Repression, corruption, and economic control, the contributors suggest, will buffer the regime against popular discontent, even when people’s economic circumstances are dire. The lack of an effective opposition, or charismatic leader, to consolidate the various social factions, leaves the population with no clear, compelling alternative. And, even if there were, the region (Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya) provides a sober lesson on the perils of regime change. In other words, things might be bad, and even very bad, but recent history indicates that they could still be much, much worse. This effectively puts the bar for the current Iranian government very low; as long as Iranians consider themselves better off than Iraqis, or Syrians, they are likely to remain risk averse and prefer to maintain the existing regime. Figure 1 in the report shows the key drivers of instability and buffers of stability identified by the expert contributors.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Question of Focus

[Q3] Given recent events, what are the trends in Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force (IRGC-QF) malfeasant activity outside of the CENTCOM AOR?

Report Preview

Experts interviewed state that they could find no evidence of recent changes in IRGC-QF activity outside of the CENTCOM area of responsibility (AOR). However, there are micro-trends that are of note, particularly for analysts focused on high risk, low probability events. Before we disentangle these trends, it is critical to place this study within the context of recent events, especially concerning the state of the Iranian economy.

The economic situation has become so untenable for average Iranians that Mr. Christopher Bidwell, JD (Senior Fellow for Nonproliferation Law and Policy, Federation of American Scientists) likens it to the environment in 2013 that drove Iran to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) negotiating table. One Iran expert ,who prefers not to be identified publicly, likens the overall dissatisfaction with the regime to levels higher than that which the population experienced in 1978. Nevertheless, none of the experts interviewed believe that either the Iranian economy or government is on the verge of collapse, just that Iran’s economy is as close to collapse as it has ever been.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc.)

Question of Focus

[Q2] Based on recent events (Accords, Soleimani, COVID), how has ballistic missile launch criteria changed? Other impacts on military readiness and response?

Report Preview

The experts interviewed for this study do not see Iran’s recent operational use of its ballistic missiles as signaling a fundamental change in its foreign policy, which they characterize as deliberate, defensive, and with a long time horizon. Additionally, domestic conditions are increasingly constraining the ability of the regime to either expend resources or absorb costs, making military conflict an untenable option. Both Iran and the United States, Behnam Ben Taleblu, of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, contends, have an interest in keeping the lid on escalation. Similarly, several contributors agree that, if nothing else, Iran is going to limit its aggression in the short-term until it has a better sense of the direction the Biden administration will take (Bidwell, Liebl, Nader).

Despite this strategic consistency, the expert contributors note changes to Iran’s approach to testing its missiles, and its willingness to use them. Since 2017, Iran has demonstrated increasing willingness to deploy its missiles operationally, culminating in the January 2020 strikes against US bases in Iraq. While its battlefield use has become bolder, Iran’s approach to testing has, conversely, become more discrete; a change some experts ascribe to increased Western attention and pressure (Nader, Taleblu).

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc.)

Question of Focus

[Q4] How have the Abraham Accords shaped Iranian activity abroad in terms of unconventional warfare (UW)?

Report Preview

The Abraham Accords normalizing diplomatic and economic relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Israel and Bahrain, as well as a less robust agreement with Sudan, represent a historic turning point for Israel. Together with the Camp David Accords (Egypt) and the 1994 Peace Accord (Jordan), the Abraham Accords bring to five the number of Arab states that have officially recognized Israel’s right to exist—a claim that states in the Gulf and Near East have denied since Israel was founded. For many Palestinians, on the other hand, the Accords are a devastating reminder of the historic indifference of the Arab states to their plight. To Iran, the Accords do not appear to represent anything new, yet. However, if the Accords led to close security ties between Israel and the Gulf states, Iran would face an unprecedented regional security environment that could impact its use of unconventional warfare tactics.

In this report, we take a broad view of Iran’s “unconventional warfare” (UW) tactics to include plausibly deniable activities such as 1) cyber and cyber-enabled influence campaigns; 2) support for, and employment of, various insurgent or auxiliary forces to serve as Iranian proxies; and 3) efforts to influence sympathetic (Shi’a and non- Shi’a) communities around the globe. The ultimate goal of each is the same: to apply indirect pressure on Iran’s adversaries to diminish their willingness or ability to fight Iran directly.

Authors | Editors: Aviles, W. (NSI); Blocksome, P. (Naval War College– Monterey); Bolduc, D. (Truth to Power LLC); Cooley, S. (Oklahoma State University); DeGennaro, P. (USARMY TRADOC G2 OEC); Dorondo, D. (Western Carolina University); Hinck, R. (Monmouth College); Kamp, A. (University of Maryland START); Koven, B. (University of Maryland START); Kuznar, L. (NSI); Levi-Sanchez, S. (Naval War College- Newport); Liebl, V. (CAOCL); Logan, M. (University of Nebraska Omaha); Maloney, M. (USSOCOM); McKee, M. (McKee Innovation Consulting); Meredith III, S. (National Defense University); Munch, R. (USARMY TRADOC G2 OEC); Oliver, R. (USSOCOM); Pike, T. (USASD / NIU); Sample, E. (Oklahoma State University); Snow, J. (USSOCOM & Donovan Group); Zaborowski, M. (POL AF / USCENTCOM, CCJ-5, CSAG); Ligon, G. (University of Nebraska Omaha); Jones, R. (USSOCOM J52 Donovan Group); Yager, M. (JS/J39/SMA/NSI); Miller, W. (USSOCOM Director of Plans, Strategy and Policy)

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Mention of any commercial product in this paper does not imply Department of War (DOW) endorsement or recommendation for or against the use of any such product. No infringement on the rights of the holders of the registered trademarks is intended.

The appearance of external hyperlinks does not constitute endorsement by the United States DOW of the linked websites, or the information, products or services contained therein. The DOW does not exercise any editorial, security, or other control over the information you may find at these locations.

Executive Summary

Global Power Competition creates more conflict, particularly when those in the arena believe “Power” to be finite, or a zero-sum game, against a defined set of actors. Both the 2017 National Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy portend of a change in our focus: inter-state strategic competition is now the primary concern in U.S. national security. While the temptation exists for us to focus on the looming giants and the conventional arsenals they build, it is too recent in our history that focusing on one class of adversary—even those who may pose an existential threat compared to a lesser peril from others—leaves us vulnerable for at least three reasons. First, as argued throughout this white paper, because Global Power Competition will result in increased violence and disruption associated with that competition, our success depends on how well we deploy our military to deter unwanted violence in competition and in war. Historically, competition for power inferred power “over.” However, a central thesis of this white paper is that competition should be for power “of.” As Chapter One deftly summarizes, influence on—or power of the people— should be central to the securing of our interests and the modern goal of global power competition.

Second, while a focus on outbidding the activities of our near-peer adversaries is an alluring and measurable objective, to do so may result in a deficit in our lessons learned over the past decades of nonstate conflict. As argued in Chapter Two, great power and asymmetric threats are not orthogonal; instead modern threats are part of an integrated network of complimentary, pragmatic, and sometimes ideological interests that interact in ways that may at times augment our adversaries or weaken our allies. In essence, behind every violent extremist organization (VEO) is a potential great power who stands to gain or lose. As a consequence, decisions we make about what appear to be today’s proximal hazards can diminish our attention on those over the horizon—the Black Swan Scenarios (i.e., Swanarios) that foment in the fissures created by Global Power Competition.

Finally, a focus on inter-state competition mischaracterizes our reality. Moreover, every potential battle increasingly appears related, as near-peer adversaries use sub-conflict strategies to accomplish their goals iteratively—pushing against each other in unexpectedly consequential domains. To create a sustained competitive advantage, the U.S. must lean into the complexity that is associated with this multi-domain competition for influence. The push to understand these globally integrated fires is paramount. To do so, new analytic frameworks must be considered in the age of disruption, as well as a deference to the historical patterns that repeat and provide a roadmap of what to do more of, less of, or differently.

In an initial effort to engage the Strategic Multilayer Assessment Community on these topics, the following White Paper is organized in five sections: 1) an introduction: anatomy of the age of disruption, 2) historical, cross-cultural, and gender perspectives, 3) analytical frameworks for globally integrated fires, 4) regional deep dives and application of the concepts, and 5) operational perspectives.

Author | Editor: Kuznar, E. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

Data

Three datasets on wealth and status distribution in Brazil were analyzed: 2015 World Bank centile estimates of income, and International Labor Organization (ILO) income by occupation data for the years 2017 and 2012.

Results

According to all three datasets, Brazil’s population is highly risk acceptant. The data provided by the World Bank examines risk sensitivity based on income, while the datasets taken from ILO examine risk sensitivity by occupation. Both methodologies show that the highest earners and the highest earning occupations are the most risk acceptant.

Significance for Risk Taking and Stability

Brazil is fairly average when compared to other countries that were measured for political stability by the Fragile States Index. However, its population is highly acceptant of risk with a mean Arrow-Pratt score of -5.68, placing it in the 94th percentile of the study. Despite a drastic decrease in Brazil’s income inequality during the last decade, coupled with numerous affirmative action plans put in place for racial and ethnic minorities, its black and female populations still suffer from a disproportionate amount of discrimination (Loveman, 2012; Ystanes, 2018). As one measure of social unrest, Brazil’s homicide rate is in the top 10% of countries; homicide and risk acceptance are strongly correlated (Daly, 2016; Kuznar, 2019b).

Implications for US Interests

The US sees Brazil as a crucial centerpiece of Latin America’s geopolitical structure and stability. Despite this, the US has weak economic interests in Brazil when compared to other larger countries with which the US has bilateral trade (OEC, 2017). The potentially anti-Chinese administration lead by President Jair Bolsonaro could prove to be a valuable regional ally for the US (Santibanes, 2018). Brazil’s risk acceptant population gives the US an opportunity to grow its political clout and economic engagement given that it can provide Brazil’s citizens with a clear path for economic improvement by enhancing opportunities for its ambitious population. If growth does not meet the population’s ambitions, then their frustrations may manifest in social unrest and increased illicit activity as people seek other avenues for improvement.

Implications for China’s Interests

China possesses strong economic and political interests in Brazil, and it has funneled large amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) from Chinese companies. Both China and Brazil are members of the BRICS association that is designed to foster increased political connectiveness between leadership of its five member states. This joint membership, as well as China’s involvement with other regional organizations, affords Brazil multiple platforms to interact with China in a political capacity (Ellis, 2017). Despite these available avenues the recent election of President Jair Bolsonaro poses several concerns for Beijing over the security of its investments, given Bolsonaro’s anti-Chinese rhetoric. Brazil’s risk acceptant population gives China an opportunity much in the same way it gives the US, making it available for influence as long as its population sees it can benefit from outside Chinese influence.

Implications for Russia’s Interests

Russia sees the recent elections in Brazil and other Latin American countries as opportunities to expand its influence and leverage within Latin America (Gurganus, 2018). The risk acceptant nature of Brazil’s population leaves it open to influence if Russia can provide support to the government and its population. In order to present itself as a viable political and trade partner, Russia has used arms deals, energy initiatives, and propaganda disseminated through media to gain favor with state actors and harm the United States’ influence at the same time. Russia is also a member of the BRICS association (Ellis, 2017).

Author | Editor: Kuznar, E. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

Data

Two datasets on wealth and status distribution in China were analyzed: 2012 World Bank quintile and decile estimates of income, and 2011 net wealth centiles compiled by the Chinese government’s Household Finance Survey.

Results

Both datasets show that China’s population is risk acceptant. The data provided by the World Bank not only show a population that is on average risk acceptant, but also demonstrate that the entire population is risk acceptant with the wealthy exhibiting the greatest risk acceptance.

Significance for Risk Taking and Stability

While China’s ethnic makeup is 91% Han, the remaining 8% number more than 100 million Chinese citizens that belong to 55 ethnic minorities, many of whom reside in China’s outer provinces and consider their particular ethnic groups autonomous from China (Clarke, 2017). The highly restrictive and autocratic practices of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) experienced by these minority groups creates the potential for further civil strife throughout the country. Examples of ethnic repression as domestic policy are the CCP’s preemptive limiting of the Uighur population’s freedom and imposing military control over Tibet (Clark, 2017; Maizland, 2019). Beijing’s growing repressive civil policies for Chinese citizens and targeted persecution toward its minorities, combined with China’s highly risk acceptant population has the potential to spark widespread civil unrest and instability.

Implications for US Interests

The US has a competitive relationship with China that occasionally turns into necessary collaboration, as both economies are interdependent and are heavily reliant on each other for success (Egan, 2019). Politically, the US has concerns with China’s intrusion into US international interests and influence (Hass & Rapp-Hooper, 2019). This makes the risk acceptant nature of China’s population and the present ethnic fissures an opportunity for the US to influence its competitor from the inside. Current unrest in Hong Kong1—where per capita GDP is approximately five times higher than the rest of China—may be an example of this potential, as China’s most risk acceptant societal elements, who are therefore more likely to protest government policies, are at the high end of the income scale.

Implications for China’s Interests

The risk acceptance of China’s population threatens its national and international interests from within. The CCP views the ethnic fissures and perceived separatist mentality of its minority groups as a direct threat to its regime stability and China’s outward BRI projects, which must go through some of these provinces (Clarke, 2017). Furthermore, inequality could fuel protest even at the higher end of the economic scale. However, risk taking can be done in pro-social ways, such as business investment and start-up businesses. If the CCP can re-start the Chinese economy and provide growth and opportunity, this potential liability could be turned into an asset.

Implications for Russia’s Interests

Russia relies deeply on its cooperative activities with China, including interacting with countries in foreign regions with the expressed purpose of weakening Western democratic values and US political influence (Oliker, 2016; Gurganus, 2018). Given its strong political and economic ties to China, Russia may stand to lose economic and geopolitical power in certain regions including South Asia and the Asia Pacific if the CCP’s legitimacy is weakened by inner turmoil from its repressed and risk acceptant population.

China’s and Russia’s Approach to Regional and Global Competition – A Future of Global Competition and Conflict Virtual Think Tank Report

Author | Editor: Popp, G. (NSI, Inc.); Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Subject Matter Expert Contributors

Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation), David C. Gompert (US Naval Academy), Dr. Edward N. Luttwak (CSIS), Dr. Sean McFate (National Defense University), Dr. Lukas Milevski (Leiden University), Dr. Derek M. Scissors (American Enterprise Institute), Yun Sun (Stimson Center), Nicolas Véron (Bruegel and Peterson Institute for International Economics), Valentin Weber (University of Oxford), Ali Wyne (RAND Corporation), Lieutenant Colonel Maciej Zaborowski (US Central Command)

Question of Focus

[Q8] How do China and Russia approach global, not just regional, arenas for competition?

Summary Overview

This summary overview reflects on the insightful responses of eleven Future of Global Competition and Conflict Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) expert contributors. While this summary presents an overview of the key expert contributor insights, the summary alone cannot fully convey the fine detail of the expert contributor responses provided, each of which is worth reading in its entirety. For this report, the expert contributors consider how China and Russia approach regional and global competition.

Please see the PDF below for the complete summary overview.

Chinese and Russian Economic Statecraft: Strategic Threat or Benign Business Activity? – A Future of Global Competition and Conflict Virtual Think Tank Report

Author | Editors: Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc.); Popp, G. (NSI, Inc.); & Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc.)

Subject Matter Expert Contributors

Dr. Kerry Brown (King’s College, London), Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation), Major Christopher Culver (US Air Force Academy), Abraham M. Denmark (Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars), Peter E. Harrell (Center for a New American Security), Anthony Rinna (Sino-NK), Dr. Derek M. Scissors (American Enterprise Institute), Andrew Small (German Marshall Fund), Dr. Robert S. Spalding III (US Air Force), Yun Sun (Stimson Center), Nicolas Véron (Bruegel and Peterson Institute for International Economics), Dr. Yuval Weber (Daniel Morgan Graduate School of National Security), Ali Wyne (RAND Corporation), Lieutenant Colonel Maciej Zaborowski (US Central Command)

Question of Focus

[Q11] How do we determine whether economic influence is a strategic threat or a benign business activity? When should the US push back against Chinese or Russian economic statecraft (such as Belt and Road projects or strategic investments)?

Summary Overview

This summary overview reflects on the insightful responses of fourteen Future of Global Competition and Conflict Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) expert contributors. While this summary presents an overview of the key expert contributor insights, the summary alone cannot fully convey the fine detail of the expert contributor responses provided, each of which is worth reading in its entirety. For this report, the expert contributors consider how to determine whether Chinese and Russian economic activity is a strategic threat or benign business activity, and when the US should push back against such economic statecraft.

Please see the PDF below for the complete summary overview.