SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

“Discrete, Specified, Assigned, and Bounded Problems: The Appropriate Areas for AI Contributions to National Security“

Author | Editor: Rogers, Z. (Flinders University of South Australia); Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

The cluster of technologies associated with artificial intelligence (AI) research and development, and the implications of these technologies across the spectrum of human activity including national security, generates a blur of fast-moving technological, political, strategic, and ethical puzzles. For all their hyper-modern veneer, tracing the trajectories of historical thought associated with these puzzles offers some much-needed clarity. To this end, what follows is an overview of three relevant trajectories. While far from exhaustive, practitioners and theorists alike in national security should have a solid grounding in these thought trajectories to facilitate reasoned decisions about AI research and development.

The overall argument asserts that research and development of AI technologies for national security should be confined to areas where discrete, specified, assigned, and bounded problems and tasks can be scientifically explored and assessed. Battlefield AI for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), target identification, sensing, and weapons tracking is such an area. The Joint Artificial Intelligence Center’s current four focus areas are appropriate (United States Department of Defense, 2019). Areas of indiscrete, unspecified, unassigned, and unbounded problems and tasks, such as in the socio-political realm incorporating population-centric cognitive and information warfare, should be approached with a high degree of caution. Risk-taking in this area is attended by high degrees of uncertainty with high exposure to catastrophic costs to domestic populations. Policy-making in AI for national security should follow a bi-modal strategy which allocates the appropriate cost/risk ratios to maximize adaptive innovation and minimize hubris.

“Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs): The Strategic Importance of Defining the Enemy”

Author | Editor: Liebl, V. (Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning (CAOCL)); Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

In this paper, as part of SMA’s Invited Perspectives series, Mr. Vern Liebl indicates that ‘violent extremist organization’ (VEO) may not be an accurate term for describing modern terrorist entities. To illustrate this point, Mr. Liebl first provides a brief history of how the term ‘VEO’ entered US defense, intelligence, and law enforcement officials’ lexicon and became commonly used. He then defines what the term ‘VEO’ means and questions whether it still appropriately applies to the organizations that have been labelled as such (namely Hezbollah, Al Qaeda, and the Islamic State). To conclude, Mr. Liebl questions whose viewpoints are taken into consideration when declaring an entity a ‘VEO’ and whether this practice is valid or “mere propaganda by those who may sympathize with it.” He also argues that the definitions of terms such as ‘VEO’ and ‘countering violent extremism’ (CVE) should have a statutory basis and cautions US government officials that assigning labels based on fear and political expediency is unacceptable and could potentially be dangerous.

United States Country Report- An NSI Aggrieved Populations Analysis

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

Data

Four datasets on wealth and status distribution in the United States were analyzed: 2016, 2010, and 2007 World Bank quintile and decile estimates of income, and 2017 US Bureau of Labor statistics income deciles.

Results

Overall the population of the US is highly risk acceptant, with peaks among the poor and the wealthiest. Furthermore, recent economic volatility has caused middle class Americans to lose wealth, which has not been regained, placing them in a loss averse and therefore risk accepting decision frame. The wealthy have been able to regain wealth lost during the Great Recession. However, their regained wealth has been in the form of more uncertain and volatile income versus traditional rents from capital ownership, possibly sustaining their high level of risk acceptance.

Significance for Risk Taking and Stability

The entire American population is arguably risk acceptant, or in the case of the middle class, loss averse. These conditions imply political risk taking across the social spectrum.

Implications for US Interests

Political partisanship, social unrest, and economic volatility are likely to decrease trust in the political system and lead to protest and major shifts in the priorities of political parties.

Implications for China’s Interests

Given the close economic ties between China and the US, volatility in American markets could jeopardize some Chinese economic interests. However, given the great power competition for global influence between the countries, losses in economic power and increased social division within the US likely play into Chinese interests and objectives.

Implications for Russia’s Interests

Given Russia’s desire to see a weakened US and democratic institutions worldwide, economic inequality, volatility, partisanship and social discord in the US presents Russia with opportunities to use cleavages between socio-economic classes to further weaken the nation.

South Korea Country Report- An NSI Aggrieved Populations Analysis

Author | Editor: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

Data

Three datasets on wealth and status distribution in South Korea were analyzed: 2015 World Bank quintile and decile estimates of income, and International Labor Organization (ILO) income by occupation data for years 2017 and 2012.

Results

South Korea is on average a moderately risk acceptant nation, as measured by World Bank data showing income by individual, and ILO data showing income by occupation. According to the most recent ILO data, South Korea has increasingly become more risk acceptant.

Significance for Risk Taking and Stability

Today, South Korea is a stable, democratic nation. However, it has a checkered past of authoritarian rule and has experienced several military coups d’état. As a risk acceptant nation, generational divides and disparities in wealth are the most likely cleavages that can lead to political instability.

Implications for US Interests

President of Korea Moon Jae-in has promised several economic reforms and diplomatic engagements with North Korea. Given the impeachment of President Moon’s predecessor, President Park Geun-hye, the success of the current administration and stable governance in South Korea is crucial to US-led negotiations with the DPRK. Latent societal inequality that can increase during a financial crisis/natural disaster/conflict etc. could threaten President Moon’s democratic mandate and ability to govern and is subsequently of significant concern to the US.

Implications for China’s Interests

Moderate regional tensions across the Korean Peninsula are favorable for China as it maintains the status quo balance of power and influence. Social cleavages in South Korea that can contribute to a degree of weakness in South Korea is correspondingly also favorable. Any monumental socio-political events in South Korea that can exacerbate inequality will also likely lead to severe instability dyadically with the DPRK however, would not be favorable for Beijing.

Implications for Russia’s Interests

Russia similarly has interest in South Korean instability insofar as it can reverse US influence and military presence. Social cleavages and inequality than can cultivate a dimension of instability that would lead to anti-Western sentiment is advantageous to Russian interests. However, high degrees of South Korean risk-acceptance have the potential to several destabilize the Korean peninsula to a point that would embroil Russian interests Barring the potential for such a scenario, South Korean stability is more advantageous to Russian interests.

“Investing In Bad Governance: China and Latin America “

Author | Editor: Perera, F. (William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies); Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

Though there have been many reports of the strengthening of commercial and financial relations between Latin America and China, comparatively few explore the conditions within the countries of Latin America that facilitated this engagement. The study proceeds as follows. The first section summarizes Chinese involvement in the region distinguishing between foreign direct investment (FDI) and official development assistance (ODA). The second section attempts to identify institutional determinants of this investment. Specifically, it differentiates between conditions that are seen as favorable to private Chinese investment and those that facilitate official Chinese development assistance. The third section outlines possible implications of Chinese involvement in Latin America.

The Future of Global Competition & Conflict Comparative Analysis: A Media Ecology & Strategic Analysis (MESA) Group Report

Authors | Editors: Cooley, S. (Oklahoma State University); Hinck, R. (Monmouth College); Kitsch, S. (Monmouth College); Cooley, A. (Oklahoma State University)

Executive Summary

This report provides a comparative analysis of Chinese, Russian, Iranian, and Venezuelan media narratives regarding visions of the future of global competition, including their instruments of exerting power (DIME), purported vulnerabilities and necessary capabilities, projected allies and adversaries, views on the future of global order (FGO), the US, and EU, as well as the available means by which global competition should be managed. Statistical modeling on these media narratives revealed concerns for informational and cultural vulnerabilities and demonstrated the importance of maximizing economic and diplomatic capabilities. China was the only nation to view the FGO positively, largely due to its projection of itself as a rising power within the global order with the economic and technological ability to succeed in future global competition. All of the nations shared in having an exceptionally negative perspective on the US and its role within the global order.

Implications on US security

- Potential Challenges to the US

- US competitors express rising insecurity within the international system threatening greater destabilization of the international order. Future conflict may increase if nations view the order as increasingly unstable, or unable to provide benefits for their participation, resulting in those nations turning more to militarization.

- While US pressure appears to be weakening Russian and Iranian abilities to compete in a future conflict, the US must ensure it maintains the diplomatic support of its allies.

- Russia appears committed to developing alternative diplomatic and economic partnerships with Eurasia and China. To maintain US advantage over Russian strength, the US should consider developing policies mitigating Russian-Chinese diplomatic and economic partnerships.

- Views of the US as in decline threatens to inhibit future US influence. The US should consider developing a strategy highlighting its diplomatic and global leadership potential, especially in areas such as technological innovation, showcasing its ability to drive future global economic growth.

- Potential Openings for the US

- US competitors appear vulnerable to US leadership regarding multilateral economic and diplomatic partnerships. US ability to maintain multilateral diplomatic and economic partnerships, especially with Western European countries, can be a force multiplier when dealing with Iran, China, and Venezuela.

- US offering of economic pacts and technology sharing could be powerful inducements for Chinese and Venezuelan cooperation. Invitations to diplomatic and economic cooperation can lessen the chances for conflict and attract partnerships if managed strategically; nations need to be able to see themselves as benefiting from the global order, especially in areas of economic growth.

- Chinese interests appear amenable to US interests economically and in multilateral institutions. US-China cooperation on economic and diplomatic issues can help support US influence and stabilize international order.

- The US media and information dominance is a significant advantage and a concern for Russia and Iran specifically. Cultural encroachment as well as the ability for the

- US to set the parameters of, and narratives on, international events among allies using media are weapons of global competition that are acknowledged vulnerabilities by Russia and Iran.

Visions on the Future of Global Competition

- Chinese narratives present the future of global competition as an economic battle centered on free trade and technological development. China views rising nationalism and isolationist policies in Europe and the US as undermining global stability and presents itself as a global leader supporting international institutions such as the UN and WTO. Successful competition requires promotion of diplomatic ties, domestic technological innovation, and continued reforms. China remains optimistic in its ability to lead the world and manage a peaceful global order.

- Russian narratives present the future of global competition as one whereby Russia is in conflict with the Western-led global order. Chief Russian concerns include its perceived domestic economic and technological declines, requiring Russia to develop greater Eurasian economic ties, especially with China; and Western information warfare causing societal disruptions and an unraveling of Russian national identity, requiring Russia to reinvest in the promotion and protection of culture across key industries. Russia is seen as maintaining its great power status and aspiring to be the main guarantor of security in a new global order; challenging US and EU backed institutions and establishing alternative multilateral partnerships to diminish US influence.

- Iranian narratives present the future of global competition through a regional lens whereby diplomatic and informational instruments of power are key for its ability to lead the Shia Crescent and combat the US attempts to isolate it. Iran is shown as under siege from an onslaught of US rhetoric and US leveraging of the international community against it and argues that US actions are in violation of international law and norms. The US is seen as aiming to divide the Shia Crescent, and Iran blames the US for its own internal weaknesses as well as for aiding in the militarization of the Middle East. To succeed in the future global order, Iran calls for greater regional unity within the Shia Crescent and greater diplomatic influence with the EU to balance against the US.

- Venezuelan narratives present the future of global competition in ideological terms where imperialist nations of all sorts, including the US, China, and Russia, compete for their own economic and political influence globally. Latin America, and Venezuela specifically, are seen as suffering the consequences of this competition, as the power brokers of the global order care little about the impacts of competition on the well-being of other nations. Venezuela sees itself as vulnerable to the outside military, diplomatic, and economic influences, especially due to its domestic turmoil and failed economic policies. Authoritarian politics, and corruption, are viewed negatively and seen as undermining humanitarian needs. Venezuela sees itself as lacking capabilities to influence foreign nations and calls for new directions in engagements with the diplomatic community and through regional economic trade relations.

Positive Drivers of the FGO: Iranian, Russian, Chinese, and Venezuelan media present the future of the global order more positively as expressions of their diplomatic and economic capabilities increase, and as mentions of diplomatic vulnerabilities and foreign competitors decrease. Media discussions of integration and alliance with other nations within the global economic system are keys to favorable projections of what the future holds for the international system. Demonstrating diplomatic voice within the global order and competency within the global economy lend themselves toward more optimistic presentations of the future.

- Positive Drivers on Nation’s Role in the Global Order: Iranian, Russian, Chinese, and Venezuelan media project a positive perspective of their nation’s role within the global order as mentions of informational vulnerabilities and articulations of necessary military capabilities increase.

- Both Russian and Iranian media discuss informational vulnerabilities within broader conversations of shoring up and maintaining cultural homogeneity related to specific regional areas of influence (FSU countries, Shia Crescent); discussions of military capabilities are framed as in defense of sovereign territory and areas of influence. For both Iran and Russia, a critical part of national identity expressed in media narratives relates to regional solidarity; one of the most dangerous aspects of Western influence is seen as its ability to wage information and cultural warfare using media.

- Chinese media present a more favorable perspective on their role within the global order as discussions on diplomatic capabilities increase, and mentions of foreign competitors decrease. For Chinese media, the role of their nation in the global order is as an emerging superpower committed to global economic fairness and equality, and demonstrating its leadership through the expression of its diplomatic prowess and lack of direct competitors.

- Negative Drivers towards the US: Iranian, Russian, Chinese, and Venezuelan media all present the US negatively. This is largely because the US is presented as an instigator of tension & conflict, a waning imperialist power, and/or a direct competitor in sectors deemed important to the nation. The perceptions of the US become more positive only as media discussions of competitors and conflict management decrease. The ability of the US to project information warfare via media is a significant concern for all of the nations; important to this concern is the underlying discussion of the US as a lawbreaker and often unfair actor in respect to the global order.

- Critical to Russian and Chinese media perspectives of the US are informational capabilities and vulnerabilities. Russian perspectives of the US become more negative as mentions of their own information capabilities and vulnerabilities are discussed. Chinese perspectives of the US become more positive as discussions of their own informational capabilities increase, and mentions of information vulnerabilities decrease.

- Positive Drivers towards Western Europe: Iranian, Russian, Chinese, and Venezuelan media perspectives on Western Europe became more positive when discussing alliances and when foreign sources were present within news stories. The importance of Western Europe overall within these presentations of the global order is twofold: First, Western Europe as a conceptual block of nations is seen as a traditional ally of the US. Diminishing the purported strength of that alliance, showing Western Europe as seeking new alliances outside of the US, and demonstrating points of common concern between other nations and Western Europe highlights the waywardness of the US in relation to the global order. Second, Western Europe is presented as generally committed to open market principles, diplomacy, and fairness. Thus, presenting the shifting alliances of Western Europe helps to cast legitimacy on the grievances and international leadership of other international actors like Russia, China, and Iran.

- Chinese media’s presentation of Western Europe was more influenced by mentions of diplomatic, informational, and economic vulnerabilities; as Chinese vulnerabilities were discussed less, presentation of Western Europe became more positive.

- In Iranian media, as discussions of conflict management increased and mentions of competitors decreased perspectives on Western Europe were more positive.

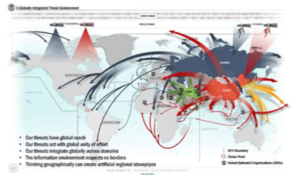

Global Competition: Planning Globally Integrated Operations

Authors | Editors: Elder, R. (George Mason University); Levis, A. (George Mason University)

Abstract

With support from GTRI, GMU worked with Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) to identify preferred, acceptable, and sustainable strategic outcomes for the U.S. and its partners. Decomposing these outcomes into causal effects and influencers served as a starting point to identify opportunities for Joint Force leaders and their inter-organizational partners to integrate military efforts and align military and non-military activities to avoid unacceptable strategic outcomes while pursuing U.S. national interests. A specific focus was to identify opportunities to counter competitor- shaping activities (particularly China and Russia) that limit U.S. freedom of action. The approach was based on challenges outlined in the Joint Staff Globally Integrated Operations Concept document. Using TIN models, GMU found that comparing U.S. and competitor regional objectives and identifying those that are in conflict with one another were a good way to highlight likely areas of competition that could develop into crises. This approach was also found useful as a means to develop potential indications and warnings. Computational experiments highlighted that U.S. and partner activities in response (counter-shaping) to one competitor’s actions can be easily misinterpreted by other competitors due to lack of context, as well as purposefully misinterpreted to use as leverage for their own counter-U.S. or counter-West campaigns. Finally, the experiments suggest that U.S. or partners taking actions to shape the environment as a prophylactic against competitor counter-west shaping activities has the potential to be misinterpreted which could create disturbances affecting regional stability and potentially lead to inadvertent escalation during periods of crisis.

“Complex Adaptive Systems“

Author | Editor: Lawson, S. (University of Utah); Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

In his interview with Lt Col David Lyle (US Air Force Academy) on 4 June 2019, Dr. Sean Lawson discusses how complexity might inform SMA’s Future of Global Competition & Conflict study. More specifically, Dr. Lawson argues that although it is important to look back at previous instances of the butterfly effect, butterfly effects are not possible to control because they are merely byproducts of a system’s existence. An inability to control certain butterfly effects, however, does not diminish the importance of expecting and planning for them, as well as developing the ability to react and adapt to changing circumstances. Dr. Lawson also speaks about the OODA Loop (observe, orient, decide, act), highlighting that US decision makers should not abandon it, but they should rethink its application and the way in which they study it. He also warns decision makers that they must maintain their trust in experts in order to avoid a potential negative feedback loop in the midst of an increasingly chaotic world. The interview continues with a discussion about potential factors that could cause a phase change in the current political and economic world order. Dr. Lawson argues that migration and climate change are the two factors that could most likely instigate this change. Dr. Lawson continues by explaining that the stability of the US’s own system is currently in flux, and it is difficult to say whether it can count on its own foundations as the bases of its stability anymore.

“Chinese Strategic Intentions: A Deep Dive into China’s Worldwide Activities”

Authors | Editors: Allen, G. (Center for a New American Security (CNAS)); Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc.); Beckley, M. (Tufts University); Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc.); Bremseth, L.R. (Computer Systems Center Incorporated (CSCI)); Cheng, D. (Heritage Foundation); Cooley, S. (Oklahoma State University); Copeland, D. (University of Virginia); DeFranco, J. (George Mason University); Dorondo, D. (Western Carolina University); Ehteshami, A. (Durham University); Flynn, D. (Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI)); Forrest, C. (US Air Force HQ AF/A3K (CHECKMATE)); Giordano, J. (Georgetown University); Gregory, J. (United States Military Academy, West Point); Hinck, R. (Monmouth College); Jiang, M. (Creighton University); Mazarr, M. (RAND); McGlinchey, E. (George Mason University); Nandakumar, G. (Old Dominion University); Roberts, C. (Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY) / Columbia University); Schurtz, J. (Georgia Tech Research Institute); Sherlock, T. (United States Military Academy, West Point); Spalding, R. (Hudson Institute), Watson, C. (National Defense University); Weitz, R. (Center for Political-Military Analysis, Hudson Institute); Wright, N. (Intelligent Biology; Georgetown University; University College London; New America); Peterson, N. (NSI, Inc.); Pagano, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Prefaces Provided By: Czerewko, J. (Joint Staff, J39); Babb, J. (US Army Command and General Staff College)

Executive Summary

This white paper was prepared as part of the Strategic Multilayer Assessment, entitled The Future of Global Competition and Conflict. Twenty-seven experts contributed to this white paper, providing wide-ranging assessments of China’s domestic and international activities in order to assess the future of China and the challenges that these activities may present to US interests. This white paper is divided into five sections and twenty-four chapters. While this summary presents some of the white paper’s high-level findings, the summary alone cannot fully convey the fine detail of the experts’ individual contributions, which are worth reading in their entirety.

Understanding Chinese motivations and strategy

There is broad consensus among the white paper contributors that understanding the reasons, motivation, and strategy behind China’s actions is critical. Several of the contributors highlight the motivations behind China’s global activities. For example, one driver of China’s actions is the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) belief that it is currently in a state of competition with the US (Cheng). A sense of insecurity about the future (Copeland) and a desire to maintain power also influence CCP behaviors (Copeland; Mazarr; Watson), as does the Party’s belief that information is inseparably linked both to the national interest and to the CCP’s survival (Cheng).

Other contributors focused on Chinese strategy. Internally, the CCP uses humiliation, distrust of the US, and China’s historical grievance to validate its rule and maintain power (Watson). Externally, China has developed a form of “strategic integrated deterrence.” This concept—which goes beyond military capabilities to incorporate political, diplomatic, economic, information, psychological, and scientific/technical capabilities—is designed to “deter and compel the US prior to and after the outbreak of hostilities” (Flynn). Given the criticality of information to regime survival, the CCP deems it necessary not only to control and influence information flow into China, but also to shape and mold the international structures that manage this flow (Cheng). Similarly, the CCP recognizes the importance of data—particularly for social control. The Party seeks to embed its model of social control into the technological matrix built and powered by Western tech companies, according to Dr. Robert Spalding III. It also seeks to expand and guide the development of tech-based businesses and social models in the future, and in order to do so, the CCP may recognize the benefits of adopting a more open system.

China and technological innovation

Several contributors indicate that China is well-positioned to become a world leader in science and technology research and development (S/T R&D), blockchain technology, and artificial intelligence (AI) technology. Dr. James Giordano, CAPT (ret) L. R. Bremseth, and Mr. Joseph DeFranco indicate that China is making significant investments in international scientific, biomedical, and technological markets for strategic purposes. Moreover, China intends to align its S/T R&D with explicit national directives and agendas to exercise its global hegemony and could leverage its S/T to disrupt global balances of order and power (Giordano, Bremseth, & DeFranco). China is also aiming to dominate the finacial technology (fintech) sector. Several Chinese companies possess digital payment systems that have major competitive advantages in the form of scale and proprietary technologies (Nandakumar). These companies could easily become market leaders if blockchain-based financial systems become the norm, and blockchains can also be used by the CCP for strategic purposes. Lastly, according to Mr. Gregory Allen, the CCP believes that AI is a “strategic technology” that will play a critical role in the future of economic and military power. Allen suggests that AI has the potential to start an “intelligentized” military technological revolution, which could give China the opportunity to narrow its military gap with the US. Consequently, China will only continue to seek leadership and make even greater use of its AI strength.

Another contributor, Mr. John Schurtz, argues that China is becoming a world leader in technology and military innovation as well. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) recognizes the importance of leading military innovation, and as a result, it has become poised to challenge the world’s most advanced militaries in the production of next generation high technology weapon systems. China will only continue to pursue ambitious innovation objectives in these areas, as is evidenced by its ‘Military-Civilian Fusion’ (MCF) development efforts.

Digital authoritarianism and Chinese regime durability

In this white paper, Dr. Nicholas D. Wright critically examines the relationship between digital authoritarianism and the durability of the Chinese regime. Although digitization may have negative effects on the durability of the Chinese regime, Dr. Wright argues that it can also strengthen the regime’s durability in the short- to medium-term by providing a plausible route for ongoing regime control while also making Chinese citizens wealthy. In addition, China’s development of a digital authoritarian regime enables its influence over other states in a competition for global influence, both through ideas and the exportation of digital systems (Wright). However, if China’s model is not broadly appealing to swing states, China may not be able to solidify its influence over these countries’ regimes and will ultimately lose this competition for influence. The future evolution of AI technology and the way in which liberal democracies adapt to becoming digital political regimes are also factors that could impact the situation (Wright).

Chinese global influence

China aspires to achieve global power status and challenge the US by extending its influence and strengthening its relationships with regions such as Europe; Eurasia; Central, West, and South Asia; and Latin America. One way in which China is aiming to increase its global influence is by increasing its economic footprint in these regions, as is evidenced by China’s expansion of trade and investments via its Belt and Road Initiative (Ehteshami & Weitz). China wants to secure access to valuable resources and create an “economic web” for its own benefit (Ehteshami, Watson, & Weitz). If these countries become economically dependent on trade with China, Beijing could use these dependencies to its advantage by using economic pressure to gain political compliance and/or undermine alliances with the US, as China did with South Korea and US deployment of a Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) system (Astorino-Courtois & Bragg).

Some regions, such as Central Asia, have reacted to Chinese influence activities with hesitation and skepticism (McGlinchey). Other regions, such as Latin America (Watson), have welcomed China’s increasing engagement and have increasingly turned to China, rather than the US, to fulfill their economic needs. European states benefit significantly from access to Chinese markets for exports and have thus welcomed Chinese economic engagement opportunities as well, despite disapproval of enforced technology-transfer by domestic European companies seeking to operate in China, international property theft, and human rights abuses by Chinese companies (Dorondo).

Another outcome of increasing Chinese influence across these regions is that pre-existing US alliances with regional states are subject to increased pressure from China. Modern US alliances across the globe, and with European nations in particular, have enabled a a high level of US prosperity and security; conversely, weakening of these relationships could lead to potential US vulnerabilities (Dorondo). The diminishment of US relations with states in the referenced regions could result in economic troubles and/or a loss of regional influence, for instance. The US has the ability to counter these Chinese global outreach activities and prevent reliance on trade with China by strengthening its own relationships with these countries and using Chinese regional shortcomings to its advantage.

Despite Chinese global influence activities that present challenges to US interests and the current global order, the US must recognize that Chinese “future elites” (e.g., students from the top universities in China) still generally respect and admire American values and institutions (Gregory & Sherlock). Thus, despite the critical narratives being propagated by the Chinese regime and the competitive nature between the US and China, a significant portion of the Chinese population still views the US in a positive light, and not as an enemy.

The future of US-China competition

The future of global competition between the US and China will be centered around economic development and technological innovation (Hinck & Cooley). Dr. Michael Beckley presents a critical perspective of China’s economic growth, arguing that it is not as impressive as it appears, and that China faces several significant restraints that prevent it from closing the wealth gap with the US. However, China will try to continue to make economic strides in an effort to catch up to the US. Prof. Cynthia Roberts cautions that, despite the importance and usefulness of international financial instruments, the US should refrain from overusing such instruments. US decision makers must consider the consequences of weaponizing finance or imposing economic costs on its opponents. Such actions could result in consequences such as countries looking to diversify to currencies other than the US dollar, like the renminbi (RMB) or digital currencies, which over time could significantly reduce US leverage and give others, including China, greater freedom to maneuver.

Managing the challenges that China presents

The US and China are competing to shape the foundational global paradigm—the ideas, habits, and expectations that govern international politics (Mazarr). This competition ultimately revolves around norms, narratives, and legitimacy. The CCP has tethered its legitimacy to achieving the goals of the China Dream proposed by Xi Jinping, which include economic success, increasing Chinese influence, and defending national territories (Astorino-Courtois & Bragg). Both internally and externally, it is critical for China to highlight its successes and portray itself in a positive manner in order to make the China Dream a reality. In its attempts to achieve these goals and shape the global paradigm, China is pursuing ambitious economic endeavors, such as the Belt and Road Initiative. China’s power is also growing in the form of its military buildup, as is evident through its increased pressure on Taiwan, its limited war with Vietnam, and its conflict with India over disputed territory (Mazarr). The challenges that China presents threaten US interests and the current world order, and therefore, it is imperative that the US successfully and carefully mitigates these challenges.

Several contributors also provide recommendations for US decision makers, namely that they must acknowledge the extent to which the US is already in competition with China and recognize the range of actions that China is taking; they must also begin to counter these actions by engaging in hard bargaining, drawing clear redlines, and remaining cautious to not provoke unwanted Chinese behaviors (Cheng). One white paper contributor, Dr. Maorong Jiang, suggests that the US might need a new strategy, utilizing a soft-power deterrence approach in order to simultaneously engage, challenge, and integrate China. Additionally, Lt. Col. Christopher D. Forrest asserts that competing in the gray zone will be an integral part of this competition, where the US must focus its time, energy, and resources. In order to effectively counter ongoing Chinese gray zone actions, the US will likely need to make some cultural and organizational changes and adapt a different lens through which to view US capability development and operations (Forrest).

Global Strategy Amidst the Globe’s Cultures: Cultures in Individual Cognition, States and the Global System

Author | Editor: Wright, N. (Intelligent Biology)

Executive Summary

How can the US make global strategy in a world both vast and rich with cultural diversity? This matters: the US shaped the global system more than any other power since 1945, and that system hugely benefited the US and much of the globe. Whoever leads the global examine two aspects of this challenge.

First, how can US policymakers make global strategy? The globe is vast, with some 193 countries, 4 billion internet users, 7000 languages, and 100 million Amazon Alexas. ‘Global strategy’ involves important activities and interests in all the continents that contain a significant fraction of the world’s population. It isn’t just grand strategy, which any state can have. It isn’t just international strategy: the global system differs from the sum of its nations, because of transnational societal networks and domains like global finance or cyber. Three defining US conflicts were global: both World Wars and the Cold War.

Recommendations:

(1) Adopt a global mindset. Policymaking should include a global vantage point.

(2) Use global system effects, not just actor-specific effects. The US may most decisively influence China, for instance, via actions with Russia, global finance or Japan.

Second, how should strategy consider global cultural diversity? Culture is the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a human group and reflects ‘how things are done around here.’ Many disciplines study culture (e.g. cross-cultural cognition and business, strategic, or political cultures) – and all of them find it slippery to define and measure. I integrate these largely disconnected fields into a mutually reinforcing framework.

I also conduct two deep dives on culture:

Culture in the individual’s mind and brain: I systematically reviewed thousands of cognitive science papers comparing decision-making in East Asia and the West. I found: (1) for most aspects of choice no robust evidence shows cultural differences (e.g. risk or fairness); (2) some differences are often discussed but lack any clear testing (e.g. East Asians care more about “face”); and (3) some aspects of choice do consistently differ, e.g. East Asians tend to engage in more context-dependent processing than Westerners, by attending more to a salient object’s relationship with its context.

Next I asked if these cognitive differences relate to strategic thinking. I compared China and the US using empirical data from doctrine, elite opinion (including interviews in China) and extant scholarship. Context-dependence, for instance, helps explain different representations of deterrence, offense and defense.

Recommendations:

(1) Apply a framework integrating cultural insights from multiple disciplines in order to anticipate both (a) competitors’ decision-making, and (b) how to influence the global swing states crucial to success in global grey zone competition.

(2) Cultural commonalties between the world’s humans greatly outweigh differences, but specific differences—e.g. context dependence—can provide operationalizable tools to cause intended, and avoid unintended, effects.