SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Question (R6.3): What is most favorable for the stability and the future of Iraq after the defeat of Da’esh: continued presence of an international Coalition or normal state-to-state bilateral relations? If a Coalition is the preferred option, what could be the “unifying factor” for a post-OIR coalition in Iraq and what situations could exist/emerge to prevent/dissolve this unity?

Author | Editor: Jafri, A. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

As the United States and its Coalition partners examine the situation in Iraq and Syria after a sustained military campaign against Da’esh, they face a significant inflection point regarding the nature of their engagement. In the United States, policymakers must decide whether continuing to work within the existing Coalition is preferable to normalizing the relationship between the United States and Iraq. The central question is whether the Coalition or a bilateral relationship would best ensure the region’s stability and secure Iraq’s future. A number of the respondents argued that continuing within the Coalition framework is preferable to pursuing a normalized bilateral relationship with Iraq. While there exist benefits and drawbacks of both relationships, it is important to examine the potential contributions and risks of each path for post-Da’esh stability in Iraq.

Working Within a Coalition

In the case of US engagement with Iraq, respondents generally preferred the prospect of continuing to work within the existing Coalition. The table displays selected responses from experts on questions related to coalition or bilateral relationships in general. Experts cited resource pooling as a significant benefit of continuing to work with the Coalition. Dr. Michael Knights of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy suggests that a coalition, including Iranian commercial partners such as Germany and France, could limit malevolent Iranian actions that run counter to Coalition interests. Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy of the University of London also recognized that a coalition would serve as a capabilities multiplier and would be able to offer more collective military capabilities.

As already noted, Mr. Hamasaeed argues that any sincere effort to bring stability to Iraq must work beyond the just the military dimension. For this reason, he suggests that a coalition would be better equipped to handle a wider mission set. Ambassador James Jeffrey of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy also supported this point, noting that an expanded Coalition will also allow states whose polity may not support a “boots on the ground” engagement to contribute to the effort. Dr. Karl Kaltenthaler, of the University of Akron and Case Western Reserve argues that the United States can use help to develop the capacity of Iraqi security forces with a possible a second-order effect of preventing Iranian entities from filling that vacuum. He also believes a coalition effort would also be viewed more favorably and would be imminently more “sellable” to skeptical populations. Separately, leading the Coalition could give international legitimacy to the United States’ objectives in Iraq, according to Dr. Kimberly Kagan and Ms. Jennifer Cafarella of the Institute for the Study of War. They argue that maintaining the Coalition would give the United States more leverage in pursuing its policy objectives. They also suggest that the domestic climate in Iraq would not favor a long-term US military commitment absent a Coalition-style framework.

Continuing the Coalition effort would not come without some drawbacks. A concern shared by a number of experts was that organization, management, and maintenance of a coalition is a complex endeavor. To that point, each member of a coalition has its own risk tolerance and domestic political limitations. Therefore, a coalition effort to stabilize Iraq may be relatively more fragile and susceptible to rupture, particularly as the narrow goals of a battlefield victory against Da’esh become actualized (Cafarella, Kagan). Additionally, working within a coalition could also pose tactical challenges to the United States. Several experts1 argue that such an environment would limit the United States’ freedom of action. Specifically, a coalition could create conditions wherein the Iraqi government and its citizens fall victim to the costs associated with being perceived as a rentier state, namely the cycle of dependency that is triggered after the receipt of large amounts of foreign assistance, and the resultant stunted development of domestic political organizations.

Operating Within a Bilateral Context

Despite the elucidated benefits of continuing with the Coalition, some respondents suggested that a managed bilateral relationship was a clearer path to stability in Iraq. Mr. Hamasaeed suggested that a bilateral relationship could hasten reconciliation between the Kurdistan Revolutionary Government (KRG) and the Government of Iraq because fewer stakeholders involved may result in a smoother process. It might also increase freedom of action on the part of the United States (Cafarella, Jeffrey, Kagan). To that end, a bilateral relationship could allow partners to efficiently map resources to their areas of expertise and orient towards their strategic interests (Hamasaeed, O’Shaughnessy). The primacy of this sentiment was also echoed by Dr. Abdulaziz Sager of the Gulf Research Center who argued for the efficiency of a bilateral relationship. This context also creates conditions that are favorable for Arab partners. AMB Jeffrey notes that bilateralism offers a level of credibility with those who seek an open-ended US commitment in Iraq. Similarly, a bilateral relationship can help the United States fend off allegations of occupation if it is not permanently basing troops in country (Kaltenthaler). Bilateralism also allows for local institutions to mature, particularly when a main source of discontent (i.e., the very existence and presence of the coalition) is allayed (Meredith).

The drawbacks to a bilateral context remain significant. Such an environment could create even more space for Iran to operate according to their interests (Jeffrey, Kaltenthaler). There will be attendant political risks, and the sum of bilateral efforts would, by nature of its lessened capabilities, be outpaced by a coalition effort (Hamasaeed). Focusing on a purely bilateral effort would also risk marginalizing United States efforts (Jeffrey, Meredith). The United States also opens itself up to having to negotiate a new Status of Forces agreement, a process that has been fraught in the past (Cafarella, Jeffrey, Kagan). Furthermore, it also opens up the United States to the possibility of being made a scapegoat if progress is stalled or difficult to establish (Meredith).

Contributors

Ms. Jennifer Cafarella, Institute for the Study of War; Mr. Sarhang Hamasaeed, United States Institute of Peace; Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Kimberly Kagan, Institute for the Study of War; Dr. Karl Kaltenthaler, University of Akron & Case Western Reserve University; Dr. Michael Knights, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Ian McCulloh, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Dr. Nicholas O’ Shaughnessy, University of London; Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Mr. Mubin Shaikh, Independent Analyst

Authors: Ali Jafri (NSI, Inc.) and Dr. John Stevenson (NSI, Inc.)

Abstract

We define space deterrence as preventing intentional attacks against space capabilities, regardless of their physical location. Intentional attacks may target space capabilities to deprive space-dependent nations of the ability to leverage space capabilities to either (1) provide indirect assistance to war fighting capabilities located in other domains, or (2) directly base weapons in space. We specify two types of deterrence (Type 1 and Type 2) corresponding to the two aforementioned ways in which space-faring nations leverage space capabilities. Type 1 deterrence concerns the defense of space assets which indirectly assist warfighting capabilities. Type 2 deterrence, on the other hand, concerns the prevention of the basing of weapons in space. Type 1 deterrence exhibits a distinctive vulnerability-credibility tradeoff due to peculiar characteristics of the space domain and how the United States leverages space to enhance other elements of national power. We conclude that unlike what classic deterrence models would predict, in space deterrence remaining reliant or dependent upon vulnerable space capabilities makes commitment to Type 1 deterrence more credible and thereby stable, lessening incentives for (kinetic or other forms of) aggression in crisis and conflict.

Citation

Jafri, A. & Stevenson, J. (2018). NSI Concept Paper, Space Deterrence: The Vulnerability-Credibility Tradeoff in Space Domain Deterrence Stability,. Arlington, VA: Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA).

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q17] As we move into multi-domain conflicts will our success hinge on being successful in every domain or can we lose in one and still be successful in the overall campaign? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Sabrina Polansky (Pagano) (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

Contributors were varied in their responses, with approximately half of the subject matter experts replying to this question with a variation of “it depends.” In other words, campaign success in a multi- domain conflict (MDC) is not solely a question of US need to dominate in all domains (or not), but instead is contingent on contextual factors that are likely to vary from one conflict to the next. Broadly, these can be grouped into the following categories, which can be examined individually or in concert: a) aspects of the conflict, b) aspects of the adversary, and c) aspects of the domain (Berkowitz; Cheng; Harris Corporation; Hitchens; Karpiscak; Steer). Figure 1 presents a set of guiding questions derived from contributor inputs, which address these categories and demonstrate the range of considerations when engaging in a multi-domain conflict.

Contributor responses as a whole focused on only one of these contextual factors—aspects of the domain. Specifically, expert discussions often emphasized the degree of domain interdependence. Multiple experts implied that space in particular is a crucial domain without which the US currently cannot “win” in any serious conflict (Cheng; Garretson; Harris Corporation; Hitchens; Steer; Weeks).5 A loss or extreme degradation in the space domain is likely to significantly affect capability in other domains (though the opposite does not necessarily hold true, with the exception of cyber). At the same time, absolute dominance in space is not required6 in order to maintain some degree of capability in other domains.

Within the context of this broader discussion of domain interdependence emerged a more concrete articulation of whether US campaign success in a multi-domain conflict necessarily hinges on success in every domain. The picture that emerged was that the US can lose in one domain—even if that domain is space—and yet succeed overall. However, this statement comes with important caveats. While the US can lose space dominance and prevail, given the degree of domain interdependence, the US cannot lose its entire capability in space and still prevail. The US must retain the ability to maneuver throughout space and other domains. However, continuing to operate (or “succeed”) in the face of partial degradation of space capabilities will come at a high cost (e.g., in national treasure or human capital) (Harris Corporation).

In order to continue fighting and ultimately suceed, the US will need to become more agile overall. (See Figure 2 for a graphic summary of the factors affecting MDC campaign success and the need for increased US agility.) This agility includes ensuring that there are appropriately robust plans and infrastructure in place to enable continued operation, whether conditions are ideal or suboptimal (e.g., domain degradation). As such, the “answer” to this question can be reformulated as follows: Success is not required in every domain, as long as the US becomes and remains agile.

Several options were in turn derived from the expert inputs for how the US might increase its agility.

Space is Different Than Other Domains and Critical to Campaign Success

The experts indicated that campaign success will depend in part on aspects of the domain(s) being invoked. These include whether any one domain is essential for the proper functioning of the others, as well as the more general interplay between and among the domains in a given multi-domain conflict. The ViaSat team underscored this interdependence, noting that:

Space systems that deliver communications, Earth observation, position/navigation/timing, missile warning, weather, etc. do not exist exclusively in space. Their delivery platforms, or infrastructure, exist in all domains including land, sea, air, space, and cyber. Thus, a network infrastructure loss in any of these domains equates to a loss in providing service or delivery to their customers that operate in the land, sea, air, space, [and cyber] domains. The inability to defend and protect systems in all domains leads to loss of service or operational capability in the operational domains of land, sea, air, space, [and cyber] (Follow-Up Communication, January 25, 2018).

However, the specific effects of dominance or loss of dominance within different domains may vary. As Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation postulates:

“dominance in different domains will have different effects. For example, losing dominance in Domain A may or may not be as bad as losing dominance in Domain B. Where you start having more problematic issues is the synergies: If I have a 30% reduction in Domain A, does that mean I’m more likely to lose all ability in Domain B?”

A theme that emerged consistently from contributor inputs is that the cross-cutting nature of space makes it fundamentally different from other domains such as maritime or land. As Dr. Cassandra Steer of Women in International Security-Canada indicated, “space is…utilized in a unique way compared to all other domains” because it (as well as cyber) is an enabler to other domains, without which those domains could not function optimally (see Garretson; Harris Corporation; Steer). In the same vein, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson of the USAF Air Command and Staff College argued that, given the US dependency on space for terrestrial command-and-control and targeting, losing space (or cyber) services would result in degradation spanning the entire joint force.8 The Harris Corporation also emphasized this point, and added that, not only would the loss of space make successful military campaigns difficult or impossible, but that if a US victory were to occur, it would come at a much higher cost than it would have if space assets had been available. Taking a global perspective, Gilmour Space Technologies added that there would also be significant weakness in other defense forces if the allied countries were to lose space communication capability in a future conflict. Cheng most powerfully illustrates the danger of current US dependence on space, by noting that:

“it will have more far-reaching effects in both the military and civilian realms if we lose space because we are not as aware of how permeating space is…. We are de facto beyond dependent on space…we are 5-year heroin addicts mainlining every couple of hours on space without realizing it.”

The Importance of Increasing US Agility

A conventional understanding of campaign success might emphasize overall US dominance. While the goal of campaign success in a multi-domain conflict might best be served by achieving dominance across all domains, as multiple experts (Armor; Berkowitz; Harris Corporation; Sampigethaya; Steer) implied, it may not be strictly necessary for the US to dominate in all domains in order to remain successful in the campaign. Instead, as Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor of Orbital ATK emphasized, the US might aim to “preserv[e] options across all domains.” Moreover, several contributors suggested that achieving, and especially maintaining, multi-domain dominance in every campaign is improbable, and thus an inadvisable goal. These contributors made the point that the US needs to be prepared for the fact that it may not be possible to succeed in every domain all of the time. The US may not always have the “home field advantage,” and thus needs to be prepared to think about trade-offs9 among domains (Hitchens; Karpiscak; ViaSat, Inc.). At the same time, the domains are highly interdependent, and each domain is highly dependent on space, which implies a potential US vulnerability that must be resolved.

Together, these points converge around the need for the US to increase its overall agility, whether aiming to “preserve options” or “think about trade-offs,” in order to achieve campaign success. It may be sufficient for the US to retain the ability to maneuver throughout the various domains, in order to “deliver the desired effects at a time and place of our choosing” (Harris Corporation). Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin10 added precision to this line of reasoning by acknowledging that dominance in all domains should not be a prerequisite for victory if the US can offset disadvantages in one domain with advantages in another. However, he offered an important caveat that, “it is difficult to conceive how the US could achieve victory or terminate conflict on favorable terms if it cannot seize and maintain at least ‘working control’ (as opposed to absolute command) of the space, air, and maritime domains.”

Dr. Krishna Sampigethaya of the United Technologies Research Center similarly emphasized the ability of the US to continue fighting in the face of attacks, rather than the necessity of defeating attacks in all domains. He offered as an example a UAV conducting reconnaissance. If a UAV relies solely on satellites for navigation, timing, and communications, it may contribute to mission failure if space is attacked. In contrast, a UAV that can fall back on other domains in the case of a space attack can continue to operate and complete the mission. Dr. Steer made a different but compatible point, noting that success in the space domain may entail preventing escalation, even if this means loss in another domain. Moreover, she argued that the waging or winning of an armed conflict in space may not be necessary to ensure the successful use of that domain to enhance other domains.

However, even partial loss of space capability could mean losing total effective capability in a second domain, and/or degradation in the space domain can have follow-on effects in other domains if those systems are not sufficiently resilient. As one example, Steer noted that, “the US [currently] lacks sufficient redundancy in many of its terrestrial systems to deal with a loss of satellite services.” Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland made a similar point, indicating that the US generally has not secured Plan(s) B to reduce space system reliance, as “protection and resiliency aren’t sexy; they aren’t ‘pointy edges’ that get funding.” She elaborated that, “We have to be prepared to have various domains suppressed or even rendered unusable for a specific conflict…including space.” Doing so would enable the US to continue fighting in the face of adversary attacks.

The current gap in preparation leaves the US with a core vulnerability. The challenge of 21st century US defense thus points to the importance of enhancing US agility, including an emphasis on building resilience into new and legacy systems and developing and exercising contingency plans—“Plans B”—to enable the US to withstand suppression or loss of capabilities in space or any other domain.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy); Faulconer Consulting Group; Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson (United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Harris Corporation, LLC; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. John Karpiscak III (United States Army Geospatial Center); Group Captain (Indian Air Force, ret.) Ajey Lele3 (Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, India); Dr. Krishna Sampigethaya4 (United Technologies Research Center); Dr. Cassandra Steer (Women in International Security- Canada); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Edythe Weeks (Webster University)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q20] What are the current international agreements, treaties, conventions, etc., governing the use of space, and what specific limitations and constraints are placed on space operations?

Author: Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

The expert contributors identified 26 separate international agreements, treaties, and resolutions (legal codes) that have implications for space operations (Figure 1). The core of the legal space regime is composed of five UN-sponsored space treaties3 centering around the 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (OST). Subsequent non-binding resolutions, and the ITU Treaty, reflect the evolving nature of space operations, and the perceived need for legal codes to develop in response.

Not all the legal codes that have implications for space operations are specific to space, however. UN general treaties, in particular regimes governing the use of force by states and the right to self-defense, inform space-specific legal codes. Furthermore, Article III of the OST states that all activities in space must be carried out “in accordance with international law, including the Charter of the United Nations, in the interest of maintaining international peace and security” (Steer).

Multilateral and bilateral security agreements (NTBT, START I, New START) place restrictions on the placement, testing, and use of weapons in space by signatory states, and efforts are underway through the UN to prevent all states placing weapons in space. Some experts also argue that the laws of armed conflict (LOAC) are applicable to space operations (Hitchens; Kasku-Jackson; Steer).

Figure 2 provides a timeline of all legal codes identified by the expert contributors, and any identified constraints they discussed. Full details of all legal codes and links to the documents are provided in Table 1. The majority of the constraints identified (21 of 40) deal with the placement, testing, or use of weapons in space, which are present in eight of the legal codes. The remaining constraints and limitations identified are, for the most part, not focused on placing prohibiting or limiting specific activities. Rather, they are designed to regulate and reduce interference in the activities of others, create accountability and transparency in space activities, and encourage compliance with international law. One exception to this is the 1978 Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD), which Dr. Cassandra Steer of Women in International Security-Canada suggests could provide a legal basis for prohibiting the use of kinetic ASATs.

Bottom Line

Overall, the expert contributors do not view the existing legal regime in space to be overly burdensome or restrictive. Starting from the basic tenets of international law—sovereign equality, non-interference, prohibition on the use of force, right of self-defense, peaceful dispute resolution—it explicitly applies these to activities in space (Steer). The emphasis on accountability, transparency (Blount), and coordination of activities reflect the underlying principles of the OST.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Dr. P.J. Blount (University of Luxembourg); Faulconer Consulting Group; Joanne Gabrynowicz (University of Mississippi School of Law); Dr. Peter L. Hays (George Washington University); Dr. Henry R. Hertzfeld (George Washington University); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Christopher Johnson (Secure World Foundation); Jonty Kasku-Jackson (National Security Space Institute); David Koplow (Georgetown University Law Center); Sergeant First Class Jerritt A. Lynn (United States Army Civil Affairs); Tanja Masson-Zwaan (Leiden University, Netherlands); Dr. George Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Dr. Xavier Pasco (Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, France); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Matthew Schaefer and Jack M. Beard (University of Nebraska College of Law); Dr. Michael K. Simpson (Secure World Foundation); Spire Global Inc.; Dr. Cassandra Steer (Women in International Security-Canada, Canada); Dr. Mark J. Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska College of Law); Joanne Wheeler (Bird & Bird, UK)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q15] What insight on current space operations can we gain from understanding the approaches used for surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings before the advent of the space age?

Author(s): George Popp (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

This report summarizes the input of 13 insightful responses contributed by space experts from National Security Space, industry, academia, government, think tanks, and space law and policy communities. While this summary response presents an overview of key subject matter expert contributor insights, the summary alone cannot fully convey the fine detail of the contributor inputs provided, each of which is worth reading in its entirety.

Approaches to Military Capabilities Before the Advent of the Space Age

Since long before the space age, capabilities such as surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings have been critical core- competencies of powerful nations. With the emergence of the space age, these capabilities expanded exponentially, both in power and precision, as well as importance to national security and defense objectives. While pre-space age approaches serve as the foundation for current approaches to these capabilities, space-based manifestations have brought clear advancements and new vulnerabilities with them. In response to these new challenges, both scholars and practitioners have started to look back to pre-space age approaches to uncover insights and lessons learned from older methods that might be used to mitigate some of the vulnerabilities in present-day systems.

Navigation, Positioning, and Timing

Before the advent of the space age, approaches to navigation, positioning, and timing capabilities consisted largely of “looking to the stars” (Sampigethaya; Samson). This, Dr. Krishna Sampigethaya of United Technologies Research Center explains, entailed “performing geometry-based calculations based on celestial bodies and their alignment with respect to the visible horizon on Earth to compute a current position, in terms of latitude and longitude, on Earth.” Today, navigation, positioning, and timing capabilities are founded in a GPS-based approach. This modern GPS-based approach has distinct advantages over pre-space age celestial navigation, according to Sampigethaya: “it provides altitude and timing data; is more scalable, accurate, and granular; and no human intervention is needed for position computing.” On the other hand, GPS-based navigation, positioning, and timing is prone to security vulnerabilities that pre-space age celestial navigation-based approaches were not. Such security challenges include the ability for potential attackers to directly target GPS satellites; to observe, disrupt, and jam GPS signals and data; and to exploit ground-based GPS systems. Despite these present-day challenges, the assertion from Victoria Samson of the Secure World Foundation, that “obviously the use of stars for navigation is not as predictable as our current navigation capabilities stemming from space,” illustrates how far the approaches to navigation, positioning, and timing capabilities have advanced.

Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Indications and Warnings

Like the approaches to navigation, positioning, and timing capabilities, approaches to surveillance, reconnaissance, and indications and warnings capabilities have advanced with the emergence of the space age. Modern satellite-based approaches to surveillance, reconnaissance, and indications and warnings have emerged as superior to the pre-space age approaches, which largely relied on air- and ground-based sensors.6 Satellites, Sampigethaya explains, make surface-to-air systems more robust, allowing for unmanned operation, greater accuracy and stealth, and instantaneous communication between air and ground systems. Moreover, Samson suggests, satellite-based systems have marginalized some of the capability limitations stemming from overflight and airspace sovereignty constraints that hamper air- and ground-based approaches. The emergence of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) offers an example of what Sampigethaya describes as a “hybrid” approach, combining elements of the pre-space age air-based approach with modern satellites to produce enhanced surveillance, reconnaissance, and indications and warnings: UAVs are “controlled by human pilots, more cost- effective, adaptive, and accurate, but rel[y] on satellites for navigation, timing, and communications.” The contributors did not specifically mention any vulnerabilities that emerge from the modern satellite- based approach to surveillance, reconnaissance, and indications and warnings capabilities, but there is no reason to believe that satellites are immune to the same security challenges (e.g., adversarial targeting, observation, disruption, jamming, and exploitation) that can limit the space-based approaches to navigation, positioning, and timing capabilities.

Insight on Current Space Operations

The emergence of the space age has propelled advancements in surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings capabilities, both in implementation and output. Pre-space age approaches to these capabilities have not been entirely forgotten, however, and in some cases these foundational approaches are still applied, albeit typically to a lesser extent than in the past. Together, the contributors’ reflections on the approaches used for surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings capabilities before and after the advent of the space age suggest four general insights.

- Controlling the “high ground” is still important.

- Space domain advancements can and should be capitalized on to maximize military effectiveness.

- There are risks and vulnerabilities associated with being too dependent on space-based approaches and capabilities.

- More efficient and effective space systems and processes are needed.

Controlling the High Ground

The military significance of controlling the high ground has persisted across the spectrum of time, both before and after the advent of the space age. With the emergence of the space age, however, its location has changed: Outer space has become the new high ground.

Surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings capabilities are all influenced by the high ground. While simply possessing or using these capabilities does not require control of the high ground, if the goal is to achieve capability dominance and superiority, controlling the high ground can be fundamental. Contributors from Harris Corporation reflect that before the emergence of the space age, superiority in capabilities such as surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings was largely dependent on “controlling the high ground, initially terrestrially and later in the air,” and ensuring “line of sight.” They emphasize the wide-ranging importance of controlling space as the new high ground:

As the new ‘high ground,’ and medium through which an increasing percentage of our communications flows, controlling space will be critical...Controlling the high ground is critical to surveillance, reconnaissance, and indications and warnings, making space situational awareness and space superiority absolutely critical to these functions. Space also offers another path in support of redundant, robust, and protected lines of communications in support of command and control, navigation, and timing.

Thus, the Harris Corporation contributors conclude that, “whoever can achieve the highest [ground] will always have the best space situational awareness. Whoever has the best space situational awareness has a military advantage in very simplistic terms over the adversary.”

Maximizing Military Effectiveness

The importance of capitalizing on space domain operations, and the enhanced military capabilities space systems offer, in order to maximize overall military effectiveness is an insight that several contributors echo.7 In considering the lessons that can be gleaned from pre-space age approaches to military capabilities, Dr. Malcolm Davis of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute reflects on the approaches to military conflict of the past. He describes a time in which warfare was “a blunt and imprecise affair” that focused on “brute force application” and “the use of attrition in battle.” This is a stark contrast to the “modern information-age” approach to warfare that has emerged since the advent of the space age. Davis’ reflection on the pre-space age approach to military conflict reveals a key insight on current space operations.

The clearest and most important aspects we [can] take from pre-space age operations is an understanding that space opens up a much greater ability to understand the battlespace, control forces, and apply precision effect against an opponent in both time and space in a manner that maximizes military effectiveness.

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor of Orbital ATK also highlights the importance of capitalizing on space-based capabilities for overall military effectiveness, stressing the importance of increasing resilience and enhancing alternate capabilities. The best approach for achieving success in this sense, he suggests, is to “normalize the use of space in military operations.” Contributors from Harris Corporation express similar thinking, and point to approaches to military capabilities in the air domain as a particularly relevant model. They argue that, “the space domain is no different than the air domain when it comes to the key mission areas. We talk about space superiority, offensive space control, defensive space control. We need to talk about offensive and defensive counter-space, suppression of enemy space defenses, and space intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.”

Avoiding Over-Dependence on Space

While the emergence of space-enabled capabilities has driven significant advancement in military capabilities, several contributors8 caution against relying entirely on space-based approaches for military capabilities. Colonel Dr. Timothy Cullen of Air University most adamantly raises this caution, arguing that military operations and capabilities “should not be wholly dependent upon information or activity from a global commons” such as space.9 His caution stems from concerns relating to ensuring the security and credibility of military capabilities and operations. Military capabilities, he believes, are “most credible and secure when founded in sovereign territory, airspace, or waters, or when the capabilities are encompassed completely within the design of the weapons system itself.”

To illustrate this point, as well as the feasibility of non-space approaches, Cullen points to US inter- continental ballistic missile (ICBM) capabilities, which he describes as the “most credible deterrent to date against threats of sovereignty by near-peer adversaries because their navigation systems are completely self-contained” (i.e., US ICBM capabilities are not dependent upon information originating from outside of the US or allied territory). ICBMs, he explains, were initially designed to hit far-ranging targets without the support of space-based timing or navigation capabilities. Moreover, the non-space- based technologies and capabilities that support ICBMs have only improved and become more affordable in the time since the initial development of the ICBM.

Ultimately, Cullen is clear in his assertion that more secure and credible non-space approach alternatives exist and should be considered. Further solidifying his argument that approaches to military operations and capabilities should not, and do not have to, be entirely dependent on space, he posits that “terrestrial and airborne approaches may remain more financially efficient and as adaptable and responsive as less capable legacy weapon systems for generations to come.”

Developing Efficient and Effective Systems and Processes

Several contributors10 suggest that surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings capabilities would benefit from more efficient and effective systems and processes. Contributors identify three areas that need improvement: integrating space operations and programs, overcoming innovation-stifling bureaucratic processes, and enhancing of space capability systems.

Integrating Space Operations and Programs

Dr. John Karpiscak III of the United States Army Geospatial Center and contributors from Harris Corporation highlight the need for improved integration of space operations and programs. Harris Corporation contributors describe US space programs as being too stove-piped and devoid of synergy. Notably, this is not the case in other domains, they explain, as the US has “been able to unlock the synergies across all the services and mission areas with a joint force” on the land, on the sea, and in the air. In the space domain, however, US space programs and operations are overly compartmentalized. This lack of synergy has clear consequences, they stress, because “to be truly effective in any domain requires all of our capabilities within that domain to understand each other’s mission areas and leverage them in support of their own mission areas. Until we can do that, we take on more risk and we will not be as effective as we could be going forward.” Karpiscak III similarly highlights the need for improved integration of US space programs and operations, arguing that “what we really need is a change in mindset on being able to integrate all of these things. It’s not just one thing—we need to be able to integrate all of them.”

Overcoming Bureaucracy

Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin and Karpiscak III highlight the need for more efficient and effective approaches to bureaucracy. Karpiscak III identifies government bureaucracy, and the glacial pace of progress that deep-rooted bureaucracy causes, as a clear problem. Bureaucracy, he explains, “creates an incremental, slow to change culture due either to an inability, or perhaps even unwillingness, of the decision makers to understand how to properly exploit the technology, and the cost and imposed acquisition limitations by federal acquisition regulations, US policy, etc.”

Berkowitz comments on the bureaucratic sources of the shortcomings of US space indications and warnings systems. He points to a lack of direction and coordination between USG and DoD agencies as the crux of the problem: “There is no clear delineation of authorities and responsibilities among US intelligence agencies to provide operations intelligence support for space indications and warnings. Nor are there adequate human and technical resources allocated for such support.” To begin overcoming these institutional deficiencies, he suggests that “the US national security establishment could gain some understanding by going back to pre-space age basics for the creation of an effective space indications and warnings system.”

Improving Space Capability Systems

Contributors from ViaSat, Inc. reflect on potential improvements to capability systems and approaches, focusing on satellite communication systems in particular. They posit a more robust approach, one in which “a multi-layered satellite architecture is available to deliver capability to users, agnostic of satellite, when needed.” Highlighting the upside of this approach, they explain that “purpose-built satellites are valuable for specific missions but the failure to take advantage of other systems can create gaps and seams. The [US] government can [instead] adopt an approach with satellite communication...in which the best available system is employed to meet mission requirements.”

Conclusion

With the emergence of the space age, capabilities such as surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings have expanded exponentially, both in power and precision, as well as importance to national security and defense objectives. Pre- space age approaches provide the foundation for current approaches to these capabilities. Space-based manifestations have brought both clear advancements and new vulnerabilities with them.

The expert contributors to this report reflect on the approaches used for surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, communication, timing synchronization, and indications and warnings capabilities before and after the advent of the space age. This reflection ultimately uncovers four general insights on current space operations.

- Controlling the “high ground” is still important.

- Space domain advancements can and should be capitalized on to maximize military effectiveness.

- There are risks and vulnerabilities associated with being too dependent on space-based approaches and capabilities.

- More efficient and effective space systems and processes are needed.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant General (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy); Colonel Dr. Timothy Cullen3 (Air University); Dr. Malcolm Davis (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Australia); Faulconer Consulting Group; Jonathan D. Fox (Defense Threat Reduction Agency Global Futures Office); Harris Corporation; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. John Karpiscak III (United States Army Geospatial Center); Dr. Krishna Sampigethaya4 (United Technologies Research Center); Victoria Samson (Secure World Foundation); ViaSat, Inc.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Question (R6.8): What is the role of the United States and coalition partners in maintaining stability as Iran, Iraq, Turkey, as other groups grapple with the Iraqi Kurdish independence referendum?

Authors | Editors: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc.)

Overview

Since the controversial September referendum for Iraqi Kurdish independence, the political stability of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and its relationship with the Iraqi government has been in crisis mode. The political uncertainty of the KRG has been clouded by the de jure resignation of President Masoud Barzani, an increase in violence and protests, and mounting economic woes. The precarious political balance between Erbil and Baghdad is not only subject to the tensions of internal Kurdish affairs, but also by the complex interests of regional and sub-state actors and the looming Iraqi parliamentary elections in May. Contributors to this response largely agree that actual Kurdish independence is very unlikely in the short-medium term and, moreover, that maintaining the territorial unity of Iraq and Kurdistan is critical to security in the region. However, contributors differ slightly on how to approach facilitating and maintaining stability in Iraq and how to balance competing interests from the KRG, sub-state actors in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and the international community.

Referendum for Independence

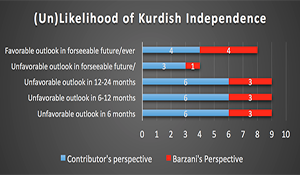

The independence referendum continues to be both a source and symptom of tension between Erbil and Baghdad. Furthermore, opposition from regional and international actors has resulted in significant setbacks for the KRG. Several experts cite the referendum as the catalyst for the territorial losses, decay of the ruling political class of the KRG, and the punitive measures the KRG has received from the Baghdad, Ankara, and Tehran—all of which makes independence more unlikely (Gulmohamad, Liebl). Concurrent with expert consensus from an earlier reachback report,1 Dr. Muhanad Seloom of the University of Exeter (UK) contends that the referendum was a gambit of political posturing intended to “maximize the KRG’s political and economic gains,” rather than an honest bid for independence. Experts are less decided on the long-term possibility of an independent Iraqi Kurdistan as can be seen in Table 1.2 Since the referendum is responsible for a large portion of the KRG’s current political strife, Dr. Gulmohamad of University of Sheffield (UK) argues that the referendum will be utilized as bargaining chip as a “long-term strategy if/when the relationship with Baghdad gets worse or fails to improve.” As Erbil struggles to consolidate resources and political unity, the fallout of the referendum continues to expose and personify the underlying tensions between the KRG and the Iraqi government.

Sources of Instability

The movement for Kurdish independence in Iraq has a contentious history that has overlapped into the many conflicts and turmoil of Iraqi politics on both a national and regional level.3 It is therefore not surprising that mechanisms of instability can be attributed beyond the political implications of the September referendum. Experts discuss three interdependent sources of controversy between the KRG and other political elements in Iraq, namely economic revenue, political representation/power, and territorial governance. Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) (with militia support of the Popular Mobilization Forces) have mounted several successful campaigns against Daesh that have reinvigorated federal authority, which resulted in the eventual reclamation of the Kirkuk governorate and other disputed territories from the Peshmerga (Gulmohamad, Liebl). These areas are coveted by both Erbil and Baghdad for their petroleum resources and smuggling routes, which both entities heavily rely on for revenue. These territorial losses ran concurrent with the disunity and fractionalization of the KRG political elite following the referendum and have left the KRG in a weak position to negotiate for a share of the resources found in the region. Baghdad’s reassertion of authority, coupled with current weakness of the KRG cited by several experts, present opportunities for negotiation and to resolve these crises (Gulmohamad, Liebl). Dr. Muhanad Seloom of the University of Exeter (UK) contends that these conflicts between Erbil and Baghdad are not new and, moreover, that “the secret behind the agreements and concessions between Baghdad and the KRG has been the elections and formations of government.” Another scholar argues that such an engagement cannot occur under the current Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) hegemony due to their personal financial interests. This is critical as a meaningful reconciliation between Erbil and Baghdad hinges on a foundational overhaul of the KRG leadership.

What Can the US Do?

A majority4 of contributors argue that the US is best positioned to play the role of mediator and facilitate negotiations5 between Erbil and Baghdad, but suggest alternate methods of diplomacy. Dr. Ofra Bengio of Tel Aviv University emphasizes the KRG as the most consistent ally to the US and that Washington should demonstrate strong support for the KRG over the Iraqi government and other Shia and Turkish interests. Dr. Abdulaziz Sager of the Gulf Research Center stresses the need for the US to maintain the current sovereign integrity of Iraq and that “anything else opens a Pandora’s box with incalculable results and consequences.” AMB James Jeffrey and Dr. Michael Knights from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy continue this calculus but recognize the importance of maintaining the KRG as a pro-Western influence element within Iraq. They suggest that Erbil-Baghdad disputes endanger this paradigm. Dr. Knights goes on to clarify that “we are not on Baghdad or Erbil’s side, we’re on the [Iraqi] constitution’s side” and so the US has a strong interest in facilitating legal resolutions to all political disputes. Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy of University of London suggests military aid to both the KRG and Baghdad could be used as a useful negotiating asset in mediation. Interests of Iran and Turkey Both Tehran and Ankara aligned with Baghdad on sanctions against the KRG following the referendum and, for the most part, share an interest in preserving the territorial sovereignty of Iraq (Gulmohamad, Jeffrey, Seloom). Turkey has a vested interest in the petroleum production of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region (Jeffrey), Iran seeks to preserve their smuggling/patronage networks (Seloom), and both entities want to ensure the KRG is free of adversarial (e.g., Kurdistan Workers’ Party [PKK] and anti-Iran Sunni) influence. While contributors note the importance of perpetuating the US as the primary ally of the KRG, experts favor cooperation between the KRG with Ankara over Tehran (Jeffrey, Knights). Such cooperation is framed in the scenario of Baghdad becoming increasingly entangled into the yoke of Iran and by granting Ankara stakeholder influence with the KRG, Erbil could better balance an Iranian controlled Baghdad. Despite the interests of Iran and Turkey, contributors have not stressed the importance of their influence on Erbil-Baghdad dynamics but again, emphasize the role of the US in forging stability in Iraq.

Contributors

Dr. Ofra Bengio, Tel Aviv University (Israel); Dr. Zana Gulmohamad, University of Sheffield (UK); Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Michael Knights, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Mr. Vern Liebl, Center for Advanced Operational Cultural Learning (CAOCL), Marine Corps University; Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, University of London (UK); Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Dr. Muhanad Seloom, University of Exeter (UK); Mr. Mubin Shaikh, Independent.

[Q12] Will major commercial space entities likely serve as disruptors or solid partners in terms of state national security interests? In the short-term (5-10 years), mid-term (15-20 years), and long-term (25+ years)? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Authors: Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI, Inc.) and Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

There was considerable variation in how the expert contributors interpreted this question, and in their assessments of the future relationship between commercial and government space enterprises. While the contributors who saw commercial entities as solid partners of the government were, with one exception, representatives of commercial space, respondents from think tank, commercial, and government communities tended to view commercial actors as potential disruptors (39%). However, the majority response among the expert contributors overall (44%) was that commercial entities might serve as both disruptors and partners.

There are two lines of reasoning for this argument. First, based on the perspective that “disruptions” can have positive as well as negative consequences, some contributors saw disruptive actors as potentially valuable allies to government. Second, others argued that technologies or actions that may be disruptive in the short-term can evolve into ordinary or standard practices in the longer-term.3 The contributors also warn, however, that whether commercial space is ultimately a disruptor or a solid partner in space will in large part depend on how the United States government (USG) decides to respond..

Furthermore, commercial actors’ organizational advantages with respect to innovation make it likely that they will become the dominant actors in space in the medium- to long-term. The effect this will have on US national security interests will be largely determined by how the USG deals with these changes. There are significant potential security benefits to be gained by partnering with commercial actors. At the same time, encouraging the growth of the commercial space sector, and relying on its capabilities and services, reduces the USG’s level of direct control. Regardless, the USG may not have much option—commercial space actors are here, and their relative capabilities are growing. If the USG attempts to limit or control commercial space actors to the point that they cannot meet their own objectives, there is nothing to prevent them from moving their endeavors to another country. This would effectively remove all but the most indirect or extreme forms of influence the USG has, and position commercial space actors to become a significant disruptor of US security interests.

Disruptors, Disruption, and Drivers

Contributors identified disruptors as actors whose behaviors and innovations trigger broad change in a system. In the context of this report’s question of focus, a commercial disruptor is a company that significantly alters (for good or for bad) the ability of the US to achieve its national security space objectives. A disruption changes the nature of the relationship between the USG and commercial space actors. The potential for disruption is determined by the extent to which USG and commercial space are dependent on, or can determine, the activities of the other. Of course, the emergence of a commercial space sector is, in and of itself, a disruption to USG dominance in space activity and technology. The question is: to what effect?.

The Impact of Private Capital

The nature of the relationship between the commercial sector and the US national security community is changing rapidly, and suggests that we may be on the cusp of a major disruption in the way US space has operated for the last 60 years. According to Dr. Moriba Jah of the University of Texas at Austin, the emergence of “angel investors and venture capitalists wanting to make huge profits” by investing in new commercial space activities has been a major driver of this change. Dr. Luca Rossettini of D-Orbit calls out “new space” start-ups, in particular, as potential disruptors as they both increase their capacities for rapid innovation and become less dependent on the USG for operating funds. It is interesting to note that this is happening at the same that the USG is increasingly looking to the commercial sector for services and innovation. As such, Joshua Hampson of the Niskanen Center believes that, 25+ years from now, the USG “may be more reliant on commercial providers for capabilities than those entities will be on the government for funding.”

The availability of private capital to commercial space could spur additional disruptions in the space service provider-user relationship. Namely, if commercial entities rather than the USG are the ones developing and operating cutting-edge space capabilities, USG attempts to regulate the sale and transfer of those capabilities is likely to become both a more complex and more contentious issue than it is today. Simply put, the interests of commercial entities—in other words, their profitability-centric business agendas—cannot be assumed to be in complete accord with the USG’s national security

objectives.

Regulation as Disruption

Several contributors comment on the impact of USG commercial regulations as a type of perennial disruptor,5 which if lifted will increase innovativeness and growth in private space sector. The ViaSat, Inc. contributors note that while the USG has “directed” space innovation until recently, today more innovation is occurring in areas in which the government has had significantly less involvement (e.g., ground segments of space systems like ATMs, etc.). They make this point in reference to USG-controlled GPS, arguing that, “since the start, the USG has gone through GPS-1 and now GPS-3. In a 35 [to] 40-year period, we’ve had three generations of space innovation. On the ground, we’ve had an infinite number of innovations.” The contributors from ViaSat, Inc. do concede that some government direction is not a bad thing, but stress that there must be “a balance of the mix” between commercial requirements for profitability and USG concern with regulating access to high-tech capabilities.

Sources of Disruption in the Short-, Medium-, and Long-Term

In addition to discussing what might make an actor a potential disruptor, contributors emphasize the need to consider what is being disrupted, and how that disruption could affect US national security objectives. Table 1 above provides a summary of space-related capabilities in which disruption and/or private-government partnership is currently happening or expected to occur.

Short- to Medium-Term

Access to and Control of Information

Dr. John Karpiscak III of the United States Army Geospatial Center identifies information as one of the critical commodities that the US will struggle to control in the coming decades. Contributors highlight three particular struggles involving space: information ownership and control, data collection, and space situational awareness (SSA). Karpiscak III discusses the challenges with data ownership and management, in terms of the extent to which commercial space entities will maintain control over who accesses their data or whether they “can be coerced, manipulated, or incentivized [by the USG] to share data with friendlies and deny access to, say, gray or red forces.” Several contributors6 also identify advances in commercial information collection and processing, including remote sensing, as potential disruptors to current practices as they make what today may be considered classified information available in the public domain. Finally, Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson of the United States Air Force Academy notes that SSA capabilities operated and owned by private companies could transfer tracking of space objects from being done “largely by a government-heavy regime to being done by some regime that’s now entirely private.”

The contributors differ, however, in their assessments of the degree to which these developments will challenge or ease the ability of the US to achieve its national security objectives. Several contributors7 see the improvements in commercial remote sensing as a potential solution to government needs. While Deborah Westphal of Toffler Associates and Karpiscak III acknowledge the potential benefit of this, they also raise concern about the loss of information control it implies. Finally, Dr. Damon Coletta of the United States Air Force Academy suggests that wider access to high-resolution imagery may “disrupt the safety of troops on the ground if suddenly a raft of competing state entities suddenly had access to levels of resolution that only the US government had beforehand.”

Medium- to Long-Term

Infrastructure

In the medium- to long-term, contributors suggest that increases in the amount of infrastructure (both in space and on the ground) could serve as an additional source of disruption. Karpiscak III argues that developments in commercial launch capabilities could make it possible for nearly anyone to launch items into space, without necessarily having to gain “anyone’s permission or consent.” Inevitably, as more actors access space, the amount of infrastructure in space will increase as well (Hitchens; Nield). Increased infrastructure will in turn stimulate the development of space-based power and transportation for on-orbit servicing (Nield; Weeden), as well as increased maneuverability (Jackson). Finally, while expanded infrastructure in space is identified as a potential source of disruption, the implications for US national security are not always clear. This may be because many of the capabilities discussed by the contributors are dual-use technologies, which many of the contributors identify as posing challenges for national security.

Long-Term

Harder to Tell

Perhaps not surprisingly, the contributors were less specific about potential sources of disruption beyond the next 25 years. Resource extraction and debris removal were the only specific capabilities mentioned in this timeframe (Hampson; Hitchens). As Karpiscak III points out: “If you look at rates of technological advance in a lot of the world economies and developments like cellphones and tablets, it’s very difficult to predict a lot of this.”

Despite this uncertainty, many contributors expect time itself to have an effect on the potential for disruption. When considering the system change aspect of disruption,10 most contributors believe that the sources and magnitude of disruptions will diminish over time as markets and commercial entities expand and mature. However, when focusing on the control aspect of disruption, Hampson sees the expansion of the commercial space sector as likely to increase disruption. He suggests that “a contemporary model exists in the computing/software industry today” where, although “companies cannot disregard US policy, [they] are large enough to…lobby against policies they disagree with and independent enough in funding to take their views to the public.”

Building Solid Partnerships

Table 1 above clearly demonstrates considerable variation in the contributors’ evaluations of the potential for government-commercial partnerships across both time and specific capabilities. This variation relates closely to the idea that innovation is intrinsically linked to disruption. The USG benefits from the innovations produced by disruptors (Jah; Rossettini), yet the more successful these actors are, the less controllable they, and their capabilities, become..

Benefits of Collaboration

Strong partnerships and collaboration are built on mutual interest. A good percentage of USG objectives in space involve national security and defense, whereas for commercial actors a business and regulatory environment that allows profitability is critical (Hampson; Stadter). Looking further out into the future, Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin suggests that the near-term establishment of routine partnerships could help decrease the extent of disruption in the longer-term. Hampson predicts that, as the orbital environment becomes busier and riskier, commercial actors will be motivated to partner with the USG to reduce the risk of “being placed under burdensome restrictions by causing problems.” Finally, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson of the United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College posits that, as the value of economic activities such as space mining and the number of US citizens in space increase, “[t]here will be a very strong push for national security services to be extended toward US citizens and their property in space, and a push to make the independent space corps look more like the US Coast and US Navy, with a strong emphasis on safety of navigation for licit commerce.”

Barriers to Collaboration

Several contributors12 indicate that commercial actors want to partner with the USG, but that barriers to solid partnerships do exist. On the government side, contributors point to regulation and security concerns (Faulconer Consulting Group; Hitchens); organizational impediments (Garretson); and lack of outreach to, and communication with, the commercial sector (Weeden). The need for profitability, and the freedom to sell their technology (Armor; Stadter), are mentioned as disincentives for commercial actors to work with the USG. On top of this, the lines of communication between the USG and commercial space sector are weak, as is the understanding of the other’s objectives and constraints (Garreston; Stadter).

Implications of Failure

If national security constraints impede the development of new technologies, as Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland believes has already happened with remote sensing and SAR, innovative commercial actors may abandon the US. Dr. George Nield of the Federal Aviation Administration points out that this is something that “we ignore at our peril because, again, the capability is going to be out there in the rest of the world. If the US chooses not to take advantage of it, we’re likely to be left behind,” a view echoed by Jim Norman of NASA. Even if companies do not relocate out of the US, we should not forget Hampson’s point that, over time, commercial space actors will likely become large enough to wield influence over policy and public opinion. Both of these outcomes would signal a loss of USG influence over some activities in the space domain.

The Verdict

Considering the contributors’ responses as a whole, it appears that “disruption” is considered a necessary part of the development of space capabilities and activities. Commercial actors’ organizational advantages with respect to innovation make it likely that they will become the dominant actors in space in the medium- to long-term. The effect this will have on US national security interests will be largely determined by how the USG deals with these changes. There are significant potential security benefits to be gained by partnering with commercial actors. At the same time, encouraging the growth of the commercial space sector, and relying on its capabilities and services, reduces the USG’s level of direct control. Regardless, the USG may not have much option—commercial space actors are here, and their relative capabilities are growing. If the USG attempts to limit or control them to the point that they cannot meet their objectives, there is nothing to prevent them from moving their endeavors to another country. This would effectively remove all but the most indirect or extreme forms of influence the USG has, and position commercial space actors to become a significant disruptor of US security interests.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James B. Armor, Jr.2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Caelus Partners, LLC; Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy); Faulconer Consulting Group; Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson (United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Joshua Hampson (Niskanen Center); Harris Corporation; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Dr. John Karpiscak III (United States Army Geospatial Center); Dr. George Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Jim Norman (NASA Headquarters); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy.); Dr. Patrick A. Stadter (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory); ViaSat, Inc.; Charity Weeden (Satellite Industry Association, Canada); Deborah Westphal (Toffler Associates)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q21] What can the US do to best facilitate development of verifiable norms that maintain a peaceful space domain?

Authors: Dr. Larry Kuznar (NSI, Inc.) and Dr. John Stevenson (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

This report describes expert views on the existence and non-existence of space norms and the challenges and opportunities norms represent for peaceful space use. At the broadest level, norms are informal but generally accepted rules of behavior that are recognized and understood by a community, 3 in this case a community of nations. Norms can emerge from either formal or informal channels, as Jonty Kasku-Jackson of the National Security Space Institute argues. Informal means of norm development include persuasion emerging from being a good exemplar of norm-based behavior, such as: the “creation of domestic legislation and regulations that serve as a model for others to adopt, publication and acceptance of academic papers, and shaping the discussion during ‘Track 2’ (non- governmental, informal, and unofficial) conferences and meetings” (Kasku-Jackson). Formal rule development examples consist of: “negotiation and implementation of binding international treaties, non-binding codes of conduct, United Nations General Assembly Resolutions, and state declaratory policy” (Kasku-Jackson).

The expert contributors generally agree on the need for norms from both informal and formal channels to maintain a peaceful space domain. The most verifiable norms, the contributors emphasize, would generally stem from more formal channels in so far as the US could facilitate norm development by leading in the responsible and transparently measurable use of space, and through the use of treaties.

Are Norms Necessary for a Peaceful Space Domain?

An increasingly large and diverse array of actors, both state and commercial, are actively seeking to exploit and explore the space domain, dramatically shifting the political context of space. The contributors indicate that states newly entering the space domain (India, North Korea, Germany, Australia), competing major powers (US, Russia, China), and commercial actors (SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, many new satellite companies) have different interests and perspectives on space. The diversity of the actors is likely to represent a range of potentially incompatible interests. According to the contributors, it appears that competing major powers are attempting to maintain their advantages within the space domain, new states are seeking affordable and perpetual access to the space domain, and commercial actors are seeking partners and initiatives that will expand the size and profitability of space markets and ventures.

Maintaining a peaceful space domain amidst the growing heterogeneity of interests in space, Dr. P.J. Blount of the University of Luxembourg notes, will require the United States to develop “norms for responsible space activities that help to ensure coordination among all space actors.”4 Norms can function to coordinate a range of interests because norms, as detailed by Kasku-Jackson, “outline good behavior and bad behavior for the [space] community.” By identifying problematic areas of space use through active engagement with diverse space actors, the United States can shape a consensus with wide-spread buy-in.

Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation concurs that norms are based on shared expectations and that a diverse array of actors in the space domain often lack these critical commonalities. Cheng questions, however, whether United States leadership and engagement with those interests will lead to stable norms that, whether verifiable or not, will help maintain a peaceful domain: Americans “talk about creating norms because we live in a rule of law society governing through mediation, and we believe that the law itself has value, separate from whoever comes before it,” but “what is the purpose of these norms and when are these norms supposed to operate?” For Cheng, norms advocates have not fully appreciated that developed and verifiable norms can also be used to entrench competing interests in ways that limit the United States’ options. In his words, the United States can “go ahead and create as many [restrictive] norms as possible,” our adversaries will sign on to these norms and hold us to them. They will make the United States “live by [its] rules,” although our adversaries may not abide by them, making these norms “self-straightjacketing.”,

Achieving Verifiable Norms: Codification, Enforcement, and Measurement

There was disagreement among the contributors on whether norms require formalization (in treaties) to be effectively verifiable. Blount concedes that “norms need not come in the form of a binding treaty,” but rather could “come in a variety of mechanisms that solidify what constitutes responsible space activities.” Blount’s optimism that non-codified norms could still be verifiable and enforceable notwithstanding, most of the contributors feel that formal agreements are the best pathway to verifiable, enforceable norms.5 The mantra that verification is enforcement typifies the views the contributors.6 Some contributors focus on the potential usefulness of formal agreements versus norms. For instance, David Koplow of Georgetown University emphasizes the usefulness of formal agreements and proposes that they would provide a vehicle for regulating space use. According to Dr. Moriba Jah of the University of Texas at Austin, these norms should be “things that promote transparency and are things that are measurable, and not measurable just by one entity but measurable by the community at large.”

In fact, many of the contributors stress the need for metrics to verify space use, which, as Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin indicates, would be difficult as it entails the measurement of behavior that may not be obvious, or have clear intent as in dual-use technologies. The contributors also lament that the US does not currently have adequate capabilities to verify actions in space and must invest resources to strengthen verification capabilities, particularly in space situational awareness (SSA) capabilities. As Kaksu-Jackson notes, SSA is a foundationalcapability thatfacilitatesattribution of activities in space and therefore supports norm enforcement.”

Conclusion

After considering whether norms are necessary for a peaceful space domain, the expert contributors address how enforcement applications of norms could provide an avenue for verification. They generally agree that an increase of diverse actors (global powers, states recently entering the space domain, commercial actors) with diverse interests (domination, deterrence, profit) increases the difficulty in developing shared norms, since norms by definition imply shared values. Given the historic difficulty in achieving effective formal agreements, the contributors share a hope that less formal norms might be an option for regulating a responsible use of space. However, they often fell back upon discussion of the value of formal agreements, exhibiting a bias toward formal rules given their explicitness. Another issue the contributors stress is the need for measurable verification of how space is being used by actors, both to mark norm violations and to support guidelines set forth in formal agreements.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Dr. P.J. Blount (University of Luxembourg); Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Faulconer Consulting Group; Joanne Gabrynowicz (University of Mississippi School of Law); Harris Corporation; Dr. Peter L. Hays (George Washington University); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Christopher Johnson (Secure World Foundation); Jonty Kasku-Jackson (National Security Space Institute); David Koplow (Georgetown Law); Dr. George Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Dr. Xavier Pasco (Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique Paris, France); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Matthew Schaefer and Jack M. Beard (University of Nebraska College of Law); Dr. Michael K. Simpson (Secure World Foundation); Michael Spies (United Nations Office of the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs); Dr. Mark Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska College of Law); Dr. Brian Weeden (Secure World Foundation),

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Question (R6.9): How does Iran prioritize its influence and presence in the region?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

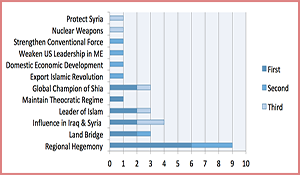

Hoping to answer the question of how Iran prioritizes its influence and presence in the Middle East, we asked fifteen experts to list—in rank order—Iran’s key interests, how it seeks to realize those interests, and how successful it is likely to be in the next 18-24 months.1 As is evident in Figure 1, a clear majority of experts consulted identified regional hegemony as Iran’s primary regional goal.2 However, while listed only once as a top three interest, Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy of the University of London argues that the primary objective of the Iranian government is the continuity of the theocracy in power in Iran. “Everything else flows from this,” he writes. Indeed, many of the other interests listed in Figure 1 could be construed as mechanisms for establishing and expanding Iran’s desire for regional hegemony and, more importantly (and implicitly), regime continuity.