SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Malicious Non-state Actors and Contested Space Operations

Authors: Rachel Gabriel (Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)) and Barnett Koven (START)

Executive Summary

This report provides an analysis of potential threats to space-based systems posed by non-state actors. It places particular emphasis on the need to consider the space domain as part of a multi-domain threat environment where domains are interconnected and interdependent. This research devotes significant attention to examining the nexus between space and cybersecurity, and to the strategic vulnerabilities posed by the increasing integration of cyber and space technologies in critical infrastructure.

It proceeds by examining the nature of cross-domain threats, and the space-cyber nexus. It then provides an overview of potential space-based threats and risks. Subsequently, the report develops a typology of malicious actors based on their motives and capabilities. Importantly, this report evaluates the risks that each type of actor might pose individually or in concert with other types of actors. While some non-state actors with malicious intent possess the requisite capabilities to directly threaten space-based systems, many groups possess only malicious intent or the requisite capabilities – not both. Consequently, considering non-state actor collaboration is especially necessary. This report also highlights how space-based capabilities, such as open-source satellite imagery, can be (and indeed, has been) exploited by nonstate actors to further their terrestrial objectives. Finally, it concludes with some recommendations to increase resiliency.

In disaggregating threatening groups by motivation and capabilities, this report finds that of all the types of actors, cyber warriors backed by nation states have the greatest potential and interest to interfere in space. In contrast, more traditional violent non-state actors (VNSAs) have the most limited capability, and probably the smallest interest, in interfering in space. Despite this, it is clear that VNSAs do have much to gain by exploiting space-based technologies (e.g., for intelligence collection, propaganda) in support of their terrestrial activities.

While many of the scenarios contained in this report are largely hypothetical, they are possible. Specifically, at least some non-state groups already possess many of the requisite capabilities and malicious intent. Moreover, there are numerous known security deficiencies in commercial space technologies. As commercialization of the space domain and the number of new commercial entrants increase, existing vulnerabilities will become more pronounced, and additional vulnerabilities will be created. In short, the expansion of multinational commercial space operations is outpacing the ability of governments to anticipate or regulate activities in this domain. Moreover, as space-based capabilities become ever more important to economic activity and terrestrial infrastructure, they also become more attractive targets.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Question (R6.5): After a long period of war, both Iraq and Syria are devastated and considerable rebuilding efforts will be necessary to make these countries economically sound again. Is there an opportunity to entice regional countries to invest and thus improve stability and inter-state relations in the region and decrease their (economical) dependence on western countries? What impact does foreign military sales have on the ultimate regional stability?

Authors | Editors: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

In studying what would motivate regional actors to support post-conflict reconstruction and development in Iraq and Syria, experts noted one concern that predominated the decision calculus of potential donors: the risk that ISIS or a similar group may resurge more quickly than efforts by regional and great power actors to foster economic stability and growth. In the absence of good governance and economic opportunities, the concern is that ISIS may regain a foothold among Sunni communities that least benefit from development aid administered by Shia-lead governments. But regional countries like Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Qatar, and Iran are expected to make significant investments and donations for post-conflict reconstruction. These countries—along with Russia and China—are also driven to invest for economic gains in terms of reconstruction contracts as well as to expand their spheres of influence in the region. This response highlights potential donors, motivations and disincentives for their contributions, as well as the role that Coalition foreign military sales may have on post-conflict stability.

Potential Donors & Their Motivations

We asked the experts which regional countries would likely be willing to donate reconstruction aid in Iraq and Syria. The table below lists potential donors as well as their incentives and disincentives for doing so. For reference, we list amounts pledged at the most recent donor conference in support of Iraqi reconstruction on 14 February 2018 that may provide insight into how willing each country might be to donate reconstruction aid in the future. As mentioned in the introduction, Ms. Jennifer Cafarella and Dr. Kimberly Kagan of the Institute for the Study of War argue that while Sunni Arab countries—particularly Saudi Arabia—are traditionally reluctant to invest in countries with Shia-dominated governments, in this case they are driven by a desire to prevent renewed insurgency. Turkey—which has historic ties to Iraq in terms of its physical proximity, affinity with Iraqi Turkmen, economic opportunities, and, more recently, its desire to return displaced populations to Iraq—might be expected to contribute significantly to post-conflict reconstruction in northern Iraq, according to Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy of the University of London (UK). Iran has the resources and competence to invest heavily in post-conflict Iraq and Syria to bring the region securely into its sphere of influence, according to O’Shaughnessy. However, he notes that Sunni populations may find extensive Shia influence unacceptable, at least in Iraq. For many, it is too soon to tell what kind of post-conflict aid might be available in Syria as the outcome of its civil war remains unsettled.

While the topic of this response focuses on regional actors, Dr. Spencer Meredith of National Defense University writes that the US risks losing political influence in the region if it yields responsibility for reconstruction to regional countries. He notes that the absence of US presence in the region would open the door wider for other actors to influence the political, social, and economic trajectory of the Middle East. Furthermore, he points out that the focus on regional actors implied in the question ignores the important roles that Russia and China are likely to play in reconstruction. Russia, along with Iran, is seeking reconstruction contracts as payback for wartime expenses in Syria and Iraq (Cafarella & Kagan, Meredith). China, which is already the lender of first resort in Sub-Saharan Africa, and is making inroads in Latin America, could very well use its One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative to increase its influence in the Middle East (Meredith).

Finally, Dr. Abdulaziz Sager from the Gulf Research Center, argues that it is not possible to entice regional countries to invest heavily in rebuilding Iraq and Syria. “There is simply no willingness by regional countries to invest in Iraq while it is still controlled to a large degree by Iran or while Syria is gripped by large degrees of uncertainty.” Dr. Sager argues that stability in Iraq and Syria will come only as a result of government reform. “And this is primarily the responsibility of the West who brought about many of the problems currently being witnessed. It would be false to assume that regional countries can be party to the guilt to force them to now take the lead in re-building these countries,” Dr. Sager notes.

Impact of Foreign Military Sales on Regional Security

The last aspect of this question asks what impact foreign military sales (presumably instead of reconstruction or humanitarian aid) would have on long-term regional stability. Contributors to this question were divided on whether the benefits of providing only military aid outweighed the risks of providing primarily social and economic reconstruction aid to Iraq and Syria. The table below outlines the risks and benefits of a military aid and sales only approach.

Risks

Experts cited two risks to relying primarily on military aid to support stability in post-conflict Iraq and Syria: a resurgence of Sunni extremism, and missing an opportunity to expand positive US influence in the region. Ms. Mona Yacoubian of the United States Institute of Peace along with Ms. Cafarella and Dr. Kagan argue that as long as Sunni communities lack economic opportunities, extremism will thrive. Furthermore, in terms of influence, the US would miss an opportunity to be seen as a credible, alternative source of support for Sunni civilians vulnerable to extremist recruitment (Cafarella & Kagan). Reconstruction funds could be used as a powerful source of leverage to pursue US national security and regional stability goals. These types of funds could also be used to push back expanding Iranian and Russian influence and stymie significant financial remunerations from reconstruction contracts. That is why Cafarella and Kagan argue that the USG must condition US aid to “ensure that developmental support empowers legitimate parties that adhere to international laws and norms.” Finally, experts also point out that once military aid in the form of weapons and equipment is given, it may be repurposed for conflicts against US interests.

Benefits

If the US preference is to leave the region relatively stable as it reduces the US military footprint there, an approach based solely on military aid and sales may be the most practical solution, according to Dr. Meredith. He notes that this approach is simple, focused, and achievable. Furthermore, he believes that it frees the US from the “occupier” and “liberalizing destabilizer” narratives and allows it to act as a “Democratic Great Power.” Along these lines, this approach allows the US to turn the table on Russia and allows it to act as a spoiler to Russia’s development and stabilization efforts.

Contributors

Jennifer Cafarella, Institute for the Study of War; Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Kimberly Kagan, Institute for the Study of War; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Dr. Nicholas Jackson O’Shaughnessy, London University (UK); Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Ms. Mona Yacoubian, United States Institute of Peace.

Malicious Non-state Actors and Contested Space Operations

Authors: Rachel Gabriel (Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)) and Barnett Koven (START)

Executive Summary

This report provides an analysis of potential threats to space-based systems posed by non-state actors. It places particular emphasis on the need to consider the space domain as part of a multi-domain threat environment where domains are interconnected and interdependent. This research devotes significant attention to examining the nexus between space and cybersecurity, and to the strategic vulnerabilities posed by the increasing integration of cyber and space technologies in critical infrastructure.

It proceeds by examining the nature of cross-domain threats, and the space-cyber nexus. It then provides an overview of potential space-based threats and risks. Subsequently, the report develops a typology of malicious actors based on their motives and capabilities. Importantly, this report evaluates the risks that each type of actor might pose individually or in concert with other types of actors. While some non-state actors with malicious intent possess the requisite capabilities to directly threaten space-based systems, many groups possess only malicious intent or the requisite capabilities – not both. Consequently, considering non-state actor collaboration is especially necessary. This report also highlights how space-based capabilities, such as open-source satellite imagery, can be (and indeed, has been) exploited by nonstate actors to further their terrestrial objectives. Finally, it concludes with some recommendations to increase resiliency.

In disaggregating threatening groups by motivation and capabilities, this report finds that of all the types of actors, cyber warriors backed by nation states have the greatest potential and interest to interfere in space. In contrast, more traditional violent non-state actors (VNSAs) have the most limited capability, and probably the smallest interest, in interfering in space. Despite this, it is clear that VNSAs do have much to gain by exploiting space-based technologies (e.g., for intelligence collection, propaganda) in support of their terrestrial activities.

While many of the scenarios contained in this report are largely hypothetical, they are possible. Specifically, at least some non-state groups already possess many of the requisite capabilities and malicious intent. Moreover, there are numerous known security deficiencies in commercial space technologies. As commercialization of the space domain and the number of new commercial entrants increase, existing vulnerabilities will become more pronounced, and additional vulnerabilities will be created. In short, the expansion of multinational commercial space operations is outpacing the ability of governments to anticipate or regulate activities in this domain. Moreover, as space-based capabilities become ever more important to economic activity and terrestrial infrastructure, they also become more attractive targets.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Chinese Worldview and Perspectives on Space: An Analysis of Public Discourse

Authors: Weston Aviles (NSI, Inc.) and Dr. Larry Kuznar (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

Corpora from three sources were examined using semi-automated discourse analysis to gauge the Chinese government’s concerns in the space domain and how these interests are articulated with general political and cultural issues. The sources were releases from the Chinese MOFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) (2011 – 2017), stories reported by CPC (Communist Party of China) News (2013 – 2014), and two months of speeches by Chinese president Xi Jinping (2014). The primary findings from the discourse are presented as Chinese perspectives and worldview with respect to the space domain and general themes.

Chinese Perspectives and Worldview Regarding the Space Domain

• In each corpus, space was infrequently mentioned when compared to other issues. The dominant concern in each corpus was the Chinese economy and development.

• The Chinese MOFA expressed much concern with the DPRK’s nuclear and missile programs and US responses to them, especially the deployment of the THADD missile defense system.

• The Chinese (MOFA) primarily mentioned space in association with danger, threats, deterrence, and the military.

• The Chinese MOFA expresses significant concern over the weaponization of space.

• The Chinese MOFA often discusses cooperation with the US and other nations on developing space technologies, but it is not clear how much of this cooperation is a government venture rather than a private sector one.

• The DPRK’s missile development was a key concern because of its destabilizing effects and because of US efforts to respond by deploying the THADD missile defense system; the radar’s reach is a perceived threat to Chinese national security.

• CPC news trumpeted Chinese accomplishments in space travel and often associated them with President Xi Jinping.

• The primary insight provided by the quantitative analysis of CPC News is that space endeavors fall primarily within the government’s domain.

General Worldview and Values

• The Chinese MOFA, CPC News and Xi Jinping’s speeches focus on Chinese economic development and economic partners.

• A common theme expressed by all three sources involves issues of governance, including advocacy of effective governance and governmental procedure.

• The United States is the country of greatest concern to MOFA as measured by the density with which the US is mentioned and the amount of emotive language (emotive themes and rhetorical devices) associated with its discussion of the US.

• The Chinese MOFA self-references China as much as expected, and portrays China in positive, futuristic and nationalistic tones.

• The most basic themes discussed by all three sources emphasize positive and future-oriented themes such as progress and success.

• Other elements included in the corpora include positive themes such as cooperation and friendship.

• The Chinese MOFA disassociates China from cyber-attacks, cyber security and democracy.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

11th Annual SMA Conference – “A Utopian or Dystopian Future, or Merely Muddling

Through?”

Author | Editor: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc.).

Conference Theme

This Conference assessed what today we rightly or wrongly perceive as historically unprecedented changes from the perspectives of politics and history, sociology, biology, information science, and technological innovation. There is a large body of scientific work that supports the notion that human societies are complex adaptive systems with emergent properties that contain core commonalities, but the actions of which cannot be predicted with certainty. Given the properties of human cognition and social behavior, the question remains: How might nations and societies best position themselves to prepare for and manage the risks associated with rapid change under conditions of fundamental uncertainty? The conference speakers and panelists addressed these issues relevant to key domains and dimensions of global security.

Conference Overview

This conference embodied the multidisciplinary nature of the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) project, by tackling issues both existential and precise, from historical and future-oriented mindsets that are inward and outward looking, and through the analysis of experts that boast a vast portfolio of background and expertise. SMA conferences allow contributors significant bandwidth to contend with the core question of how the USG should think, understand, and plan a path to US prosperity in an environment where uncertainty dominates predictability. Many of this conference’s panelists based their subject matter on the fundamental notion that technological innovation is not only changing preconceived notions of national security, but the nature of society itself. Panelists also contended that many of the principles of warfare and human behavior remains the same; thus the vital task is deciphering where, and how, the USG’s calculus needs to adapt or to persevere.

The fields of innovation and technology explored in this conference were contextualized by what experts argued is a flawed appraisal of strategic landscapes that do not reflect new and unfamiliar forces. Doctrine and policy leftover from the Cold War have failed in many respects, but shifts in geopolitics are not wholly accountable for these shortcomings. The ubiquity and effectiveness of technology has, perhaps not changed the fundamental nature of conflict, but rather the personality. Many panelists suggest that the strategic landscape now favors the ability to influence allies and adversaries over our ability to implement quick and lethal force; furthermore, the path to such influence must begin with a recalculation in our strategy to reflect this reality. Assessing the importance of influence in the strategy, operations, and internal functions of the DOD must occur across the board from the policy maker, operator, analyst etc.

A theme of concern over the integration of emerging and under-utilized technology and knowledge into our systems, planning, and strategy was expressed throughout the conference spanning USG’s functions and theaters of operations. Recognizing the applicability of artificial intelligence (AI) in military applications, or analyzing social media in socio-political movements, or collecting data that reveals technological and cultural divides; is not enough. Quickly and efficiently transforming such advancements into useful tools and more competent strategy must be executed at a system level in order to maintain US superiority. Updating our complex systems, planning processes, and strategy still presents the inherent difficulty that is expected in any information environment; nevertheless, panelists detail notable results from these shifts and advise following the veins of success and learning from failed models and pursuits.

[Q5] Is it possible to realistically quantify the economic impact of warfighting events in space (e.g., increase in insurance costs for commercial satellites, stock market perturbations of a space attack, change in consumer behavior due to disruption of communication or PNT services)?

Author: Weston Aviles (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

This report captures the input of 19 responses contributed by experts from the National Security Space community in the US and an array of commercial space actors in the US, Australia, Italy, and Norway. Industry perspectives on this question are surprisingly varied in both their explicit responses (i.e., “yes,” “difficult,” “impossible,” etc.) and their use of methods for assessing the fallout of hostility in space. While the contributors offer a variety of useful insights, there does not appear to be an easily accessible and comprehensive analysis of the financial impact of conflict in the space domain. In fact, due to the cascading nature of warfighting events in space, contributors disagree on whether any analysis would produce a satisfactory answer, but the clear consensus is that further research needs to be done on this topic.

Not an Easy “Yes” or “No” Answer

Only three contributors4 responded to this question using a “yes” or “no” binary, suggesting that a more nuanced approach to the feasibility of modeling the economic impact of warfighting events in space is necessary. Contributors from Caelus Partners, LLC contend that a holistic simulation can quantify the impact of warfighting events in space. Toward this same end, Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin and contributors from Harris Corporation point to previous work by the Department of Commerce as useful groundwork that might be combined with applied “economic principles and econometric(s).”5 On the other hand, several contributors6 suggest that it would be virtually impossible to accurately measure such a shock to a system that is “integrated into almost every nook and cranny of the economy” (Hitchens). Despite these more categorical assertions, the central theme highlighted by the majority of the experts is that the economic impact of warfighting events in space can at best be measured in relation to certain aspects of commerce that are contingent on space operations. However, even these estimates will be unable to account for the second- and third-order economic impact of warfare in space.

Broadly speaking, the expert contributors tend to define first-order effects as more easily measurable, direct damage to space assets that might be calculated by material replacement costs. Second-order effects involve damage to, or degradation of, systems that are dependent on space systems, while third-order effects involve the more intangible opportunity costs resulting from second-order effects. For example, first-order effects of the destruction of a Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) satellite might be measured by the cost to replace that satellite. Calculating the costs associated with second-order loss or degradation of point-of sale (PoS) and ATMs capabilities that rely on the PNT satellite may be possible, but is likely difficult to do. Finally, calculating the third-order loss of potential revenue of all businesses affected by the loss of those systems is essentially impossible to quantify. Table 1 below7 outlines potential effects of warfighting events in space explicitly mentioned by contributors, and whether those effects can be realistically quantified.

Methods and Challenges of Quantification

As can be seen in the table above, the contributors who contend that quantifying the impact of warfighting events in space is possible, limit their assessments to only first-order effects and second-order effects only for select space-dependent systems. Given the challenges of quantification, contributors indicate only a few approaches that could be used to measure consequential outcomes. For example, the contributors from Chandah Space Technologies suggest a ground-up methodology10 for aggregating the equities of stakeholder assets that would be affected and “summing it across all the categories of interests.” The Harris Corporation team intimates that other approaches are being taken: “insurance companies and financial underwriters for commercial satellite owner/operators have most likely done more detailed estimates of these impacts.” However, they also caution that the “associated variability and uncertainties are likely to pose significant uncertainties to many of their estimates and, for all practical purposes, represent just a fraction of the overall financial impact.” In short, multiple contributors agree that there are fundamental challenges to any methodology aimed at capturing a comprehensive picture of the economic fallout of conflict in space.

How Bad is Conflict in Space?

Almost half of the contributors12 stress that the impact of a warfighting event in space would be a historic event with no comparable precedent (and therefore, extremely difficult to quantify for this reason). The Gilmour Space Technologies team writes of significant satellite damage leading to the “equivalent of a limited nuclear war in terms of economic damage,” and the Adranos Energetics team categorizes such an incidence as likely to result in a “total panic” in the financial world. To illustrate further the magnitude of such a warfighting event, two experts discuss how current political tensions surrounding the space domain are already limiting economic growth, commerce, and cooperation in peacetime.13 These effects would be magnified several times over in any warfighting scenario, and thus speak to the seriousness of such a potential event.

Contributors

Roberto Aceti (OHB Italia, S.p.A., Italy); Adranos Energetics; Brett Alexander (Blue Origin); Anonymous US Launch Executive; Chandah Space Technologies; Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Caelus Partners, LLC; Elliott Carol3 (Ripple Aerospace, Norway); Matthew Chwastek (Orbital Insight); Faulconer Consulting Group; Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Harris Corporation, LLC; Dr. Jason Held (Saber Astronautics, Australia); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; John Thornton (Astrobotic Technology); ViaSat, Inc.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q18] What are the principles (e.g., flexible vs. controlled response; proportionality, etc.) upon which international policy makers should develop response options for aggression in space? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author(s): Dr. John Stevenson (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

Upon considering the question of focus, several expert contributors argue that it is confusing or even misleading (Cheng; Gallagher; Hertzfeld; Masson-Zwaan). The contributors maintain that this confusion comes from two sources: the ambiguity of the language used in the question and the ambiguity of existing space treaty law. Noting the inherent contention in the legal realm of space, the contributors as a whole nonetheless work to articulate how the US might derive a set of principles for response to aggression in space. Contributors divide into two camps: those who argue that principles already exist that can be used to guide a response to aggression, and those who argue that these principles are—and must be—emergent. Although distinct reasons are given between the two camps, the chief principle on which all camps agree is what we might call the “precaution principle.”

Two Sources of Question Ambiguity: Terminology and Existing Space Law

Dr. Nancy Gallagher of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland believes that the phrase “international policy makers” is vague, and Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation contends that the phrase represents “the language of UN bureaucrats and academics in the arms control community” rather than a pertinent characterization of decision-makers with power. Cheng queries: “what is an ‘international policymaker?’ You mean US policymakers? Or, do you mean the international consortium of space policymakers that meets in Geneva or someplace like that?” His elaboration of his

confusion is worth quoting at length:

One of the big problems we have when you use terms like “international policymakers,” is that you actually are talking about a conglomeration of different groups and entities with very different perspectives. You have space technical policy people. You have space policy people from different countries. You have experts on countries, some of whom have some knowledge of those countries’ space policies.

In addition to the ambiguity inherent in the language, contributors cite the ambiguity of current space law. For many expert contributors, it was difficult to articulate principles of response because the antecedent action—aggression in space—is poorly defined in the law. According to Dr. Henry Hertzfeld of George Washington University, “a lot of these things are still not well defined in the space environment. There is no good definition of a weapon, for example. There’s no good definition of what an armed attack might be.” Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland echoes this viewpoint, noting that, “There is no legal or agreed definition of ‘aggression’ in space; either under the UN Charter or in any other body of law.”

Are There Already Principles of Response Appropriate to the Space Domain?

In determining specific principles of response to aggression in space, contributors divide into two groups: a camp that argues that principles of response apposite to the space domain already exist in international law, and a camp that forwards that whichever principles exist will require further development in order to be useful in the space domain. The first camp largely defends existing principles as requiring little to no amendment for use in developing responses to aggression in space. The second group postulates that the principles will emerge out of interactions in the space domain, as long as actors curate their understanding and responses to potential adversarial action with all deliberate speed.

Principles of Response to Aggression Already Exist

Contributors in the first group identify the United Nations Charter, the Outer Space Treaty (OST), and the Law of Armed Conflict as the three sources of principles governing responses to aggression in space (Hitchens; Johnson; Nishida; Spies; Steer). Christopher Johnson of the Secure World Foundation explains that, “Article III of the Outer Space Treaty makes it clear that general international law, including the UN Charter, apply to the activities of states in the exploration and use of outer space.” Michael Spies of the United Nations Office of the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs further points out that in the United Nations Charter there are “a number of principles applicable to the development of international policy responses to prevent aggression in outer space.” The experts argue that, just as they do in other domains, these principles can guide policymakers in formulating responses to aggression.

Principles from the United Nations Charters and the Outer Space Treaty

In fact, the principles of the UN Charter, reiterated in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, are the foundational principles for policymaking in space, according to Johnson, because the language of the Charter itself specifies that there is “a hierarchical relationship between special regimes such as space law,” such that the UN Charter “takes precedence of any special regime of international law.” Michiru Nishida of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan buttresses this view, and suggests that the “most important principle that should be reaffirmed would be the application of existing international law and obligations to all outer space activities, scientific, civil, commercial and military.” He stresses the importance of existing international law governing all activities, inclusive of military activities, because “some states dispute the scope of agreements adopted at UNCOPUOS…claiming that the mandate of the UNCOPUOS only deals space activities other than military.”

The specific principles that Spies and Johnson explicitly identify within the UN Charter/OST treaty system as governing responses to prevent armed conflict in space are: The principle for states to “settle their international disputes by peaceful means” (Spies) and long-standing principles such as “good faith, pacta sunt servanda, the sovereign equality of states, non-interference, non-aggression, the prohibition on the use of force, the right of self-defense” (Johnson), as well as the precautionary principle.

Principles from the Law of Armed Conflict

Offering a concurring, but more narrowly-tailored view, several experts (Beard; Simpson; Steer) identify the Law of Armed Conflict (jus in bello and jus ad bello) as the most applicable principle of response to aggression in space. Jack M. Beard of the University of Nebraska College of Law agrees that the more concrete legal debates about principles and responses to aggression are situated within the Law of Armed Conflict, noting: “The more you study space and the importance of things like GPS satellites, the more that you are able to make an argument that an attack generating huge debris fields might violate the Law of Armed Conflict.”

According to Dr. Cassandra Steer of Women in International Security-Canada, the most important principles drawn from the Law of Armed Conflict for the space domain are the “principles of proportionality and precaution in attack.” Dr. Michael K. Simpson of the Secure World Foundation notes, however, that the principle of proportionality, when applied in the space domain, “may be complicated by the asymmetry of impact of actions in space.” Expounding further, he warns that “eliminating a single satellite upon which a country depends for critical terrestrial services clearly has an effect that is disproportionate to that of eliminating a single satellite in the fleet of major space faring countries with multiple options to work around the loss.” Responses to aggression that target space assets trigger proportionality concerns through their humanitarian impact, according to Spies: the “destruction of dual-use satellites could negatively impact essential civilian infrastructure, health-care services and humanitarian operations,” which rely on “satellite communication, navigation and timing, and imagery networks.” Precaution, as a principle guiding militarized responses in the space domain, dovetails with the doctrine of necessity, Steer observes, because the “use of force must only be employed when the aggression is “instant, overwhelming, and leav[es] no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.”

Principles of Response to Aggression Are (and Must Be) Flexible

The second group of contributors, which argues that principles of response are emergent, prefer to categorize “aggression” as an unwanted behavior in an interdependent social system (Bevilacqua; Broniatowski; Caelus Partners, LLC). Dr. David Broniatowski of George Washington University notes that systems that operate in the space domain are designed and therefore possess an architecture that defines how specific components will carry out functional requirements to achieve needed capabilities. Appropriate selection of this architecture can enable flexible response options, such as the ability to carry out new capabilities, or resilience to attempts to disrupt existing capabilities, in the event of unexpected behaviors or other changes in the space environment. Conversely, selection of an inappropriate architecture can inhibit flexible response options by making changes too complex or costly to implement after the system has been fielded. The contributors from Caelus Partners, LLC hypothesize that this architecture can be leveraged to “create a community for the purpose of the coordination and management of participant activities.”

The contributors in this second camp jointly identify three specific principles of response as being effective within the emergent social system of the space domain: flexibility with firmness, precaution, and multi-lateral punishment.

The first principle of response is being “flexible, but firm,” as Adam Gilmour of the Gilmour Space Technologies elegantly puts it.3 Gallagher delineates the mechanisms of how this principle would work in practice. Respondents to aggression should “determine the objective of the response”:

If something bad happens, you could say, ‘Well, our primary objective really is to just condemn the bad thing.’ Or, the US could say, ‘Our primary objective is to punish the bad thing, or to reverse whatever gains the bad actor achieved so they don’t get any kind of military advantage for it.’

In other words, actions taken in response to aggression should have end goals in mind before they are undertaken. Because the goals of the response may vary by actor and technological capability among other factors, flexible but firm responses are seen as ideal in this view.

The second principle of response is best described as a “precautionary principle.”4 Gallagher describes this principle in the space domain as one of prudence, so that responses to aggression occur with all deliberate speed because an “informed response is better than a quick one”:

Don’t act before you know what actually happened. And it may or may not be obvious what happened—whether it was a deliberate attack, whether there was some form of inadvertent or human interference, whether it was a satellite malfunction, whether it was a result of a natural hazard.

Information helps prevent a combination of errors inherent in the space domain that could result from mis-attribution, mis-estimation (of harm), and mis-identification of what the event was. Specific factors used to determine response “could be derived from three elements: characteristics and purpose of the spacecraft; operational environmental factors, and demonstrated behavior,” the contributors from ViaSat, Inc. maintain. It should be noted, however, that Broniatowski does not endorse the precautionary principle as equal to the principle of flexibility. In his view, precaution is not applicable in all cases, whereas flexible response options should allow for selection of a response based upon what is contextually appropriate.

The third and final principle identified by this camp is that of multi-lateral punishment. For these contributors, acting as a community grants coordinating nations a number of agenda-setting and distributional advantages. As one example of the potential role of this community, Dr. Riccardo Bevilacqua of the University of Florida posits that “a nation engaging in aggressive behaviors in space should be banned from operations for a certain time, in proportion to the gravity of its actions.” Nations operating within the community, if they possess a technological advantage over the aggressive actor, could, according to the contributors, enforce such a ban.

Conclusion

In conclusion, though several subject matter experts note sources of ambiguity in the question of focus, the experts as a whole go on to identify sources of principles that can govern responses to aggression in the space domain. These experts can be categorized into two groups: one that draws principles of response from existing laws and practices; and another that believes that new or emergent principles, specific to the space domain, are necessary. Across these two groups of experts, several explicit principles emerge:

- The resolution of conflict by peaceful means

- Respect for the sovereign equality of states operating in the space domain

- The principle of proportionality

- The principle of precaution

- Flexibility with firmness in response

- Multi-lateral punishment

Although distinct reasons are given between the two camps, the chief principle both camps articulated is the principle of precaution, largely due to the potential for suboptimal outcomes resulting from the low-information environment of the space domain.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Dr. Riccardo Bevilacqua (University of Florida); Dr. David Broniatowski (George Washington University); Caelus Partners, LLC; Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Faulconer Consulting Group; Joanne Gabrynowicz (University of Mississippi School of Law); Dr. Nancy Gallagher (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Harris Corporation; Dr. Peter L. Hays (George Washington University); Dr. Henry R. Hertzfeld (George Washington University); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Christopher Johnson (Secure World Foundation); David Koplow (Georgetown University Law Center); Tanja Masson-Zwaan (Leiden University, Netherlands); Michiru Nishida (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Japan); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Matthew Schaefer and Jack M. Beard (University of Nebraska College of Law); Dr. Michael K. Simpson (Secure World Foundation); Michael Spies (United Nations Office of the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs); Dr. Cassandra Steer (Women in International Security-Canada, Canada); Dr. Mark J. Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska College of Law); Charity Weeden (Satellite Industry Association, Canada)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q13] What are the national security implications of increasingly accessible and affordable commercial launch services? Are these the same for the US and near-peers or states with emergent space capabilities? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Authors: Dr. John Stevenson (NSI, Inc.) and George Popp (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

The experts solicited in this effort agree that there will be wide-ranging national security challenges and a few benefits arising from decreased launch costs. The challenges are largely derived from two structural changes to the space domain: more actors and a wider diversity of payloads. The subject matter experts indicate that changing commercial launch technology alters the monetary costs of the types and timing of deliverables national space programs can produce. These potential transformations of national space programs affect: military procurement patterns, environmental destruction, informational supply chains, and military space operations.

Less is More: More Actors and More Junk

The diversity and number of actors accessing space and the types of objects in space is increasing over time, seemingly exponentially. According to Dr. Malcolm Davis of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a suite of commercial entities, “SpaceX, Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic, and Stratolaunch, amongst others,” are “either launching payloads or soon will be, in new ways that opens up access to space to a broader customer base and at a lower cost and with greater responsiveness.”6 Dr. Deganit Paikowsky of Tel Aviv University observes that commercial entities are one of the “two new types of players [that] joined global space activity” due to decreased costs to launch. Historically, larger incumbent companies, such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin, have used government corporate subsidies to drive their product cycles. Lowered costs to launch have added “(a) small and developing countries [and] (b) private sector players” to the mix of actors in space.

More actors with access to space has led, unsurprisingly, to more material in space of varying quality. Dr. Damon Coletta of the United States Air Force Academy incisively notes that what “looks like a change in launch services” and costs is actually “an advancement and diffusion of technology for building small, lightweight, highly capable payloads.” Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin maintains that further increasing the number of nation-state and sub-national actors able to access space…risks continuing to make the space domain more congested and complex. Such increased congestion and complexity will impose additional resource burdens on space domain awareness capabilities and could create additional debris or other hazardous operating conditions that pose risks of mishaps.

The diversity of payloads, Dr. Luca Rossettini of D-Orbit postulates, creates physical danger from an atmosphere of cheap objects threatening the integrity of government-sponsored space systems:

The increasing and unregulated launch of satellites—23,000 satellites have been forecasted for the next ten years, and this estimate grows every three months—may pose several risks. In fact, most of these satellites are designed to be manufactured using COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) components. Hence, they are less reliable than government-type satellites, and their death rate will be higher than the current average.

How the Implications Differ (or Not) Across the International System

The national security implications that the subject matter experts identify are best categorized into four baskets: military procurement deliverables, environmental destruction, informational supply chains, and military space operations.

One implication of increasingly affordable launch services that the experts consistently identify is how launch services shift the military procurement deliverables of national space programs. Nations with advanced commercial space sectors would gain more value for their spending and allowing for new timelines of development within both emerging and legacy national space programs, experts postulate. Elliot Carol of Ripple Aerospace observes that any country’s “military budget goes a lot further,” including the United States, if those countries are no longer “paying ULA a couple hundred million dollars for the next launch, but are paying SpaceX $62 million a launch.”

Although saving money in space programs appears to be primarily an economic benefit, these cost savings yield steep national security implications. Shifting the necessary allocation of resources affects the whole of countries’ defense industries and the distribution of capabilities across the international system to those countries whose responses to these changes are strategic and forward-thinking. Berkowitz argues in this vein: “An advantage should accrue to the side that mitigates the risks and takes advantage of the opportunities created by accessible and affordable commercial launch services with the greatest speed, agility, and consistency.

Other exerts concur with Berkowitz that cheaper, changing procurement options shape space program management and initiatives. Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson of the United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College points out that lowered costs allow the United States to “affordably field entirely new military capabilities (Space-Based Radar/MTI, Space-Based Missile Defense, Space-Based Terrestrial Strike).” This innovation, Dr. Moriba Jah of the University of Texas posits, stems from the commercial competitiveness of a larger market to win government contracts, which in turn gives public sector procurement managers increased program design options. He states: “In times past, government actors had very specific kinds of providers and launch opportunities, whereas now, with cheaper access to space and more launch providers, governments can take multiple rides and have many choices.”

Some experts also agree with Berkowitz that only countries that move quickly will gain advantage, but argue that the United States has been slow to capitalize7 on these transformations, reducing the relative competitiveness of the American space program. Dr. Davis warns that “ironically, large, expensive, fully expendable rockets, which take months to prepare for launch and cannot be reused, are still the focus of NASA with its ‘Space Launch System’ (SLS) and United Launch Alliance (ULA) with the Atlas and Delta family of vehicles.” Experts from Harris Corporation, LLC urge American policymakers to “rethink ‘how we do space,’ writ large. The legacy requirements for large, highly sophisticated, redundant systems with lots of fuel, multiple backups, and long service lives may no longer be required to the same extent as today.” The national security implications of these changing options for procurement pushed Dr. Davis to raise a key question: “How will these traditional launch vehicle technologies compete with reusable rockets, airborne launch, and, ultimately, spaceplanes in terms of cost competitiveness, efficiency, and responsiveness in the next two decades, particularly as reusable launch systems mature over time?”

The second implication of these commercial technologies is the environmental destruction from so many actors’ increasing ability to place more materials of varying quality into orbit and potentially affect all states equally. Dr. Riccardo Bevilacqua of the University of Florida cautions that actors in the space field are approaching access to space as if it were an infinite resource, and reduced prices are enabling operators to reduce the quality of their satellites and to launch more, relying on redundancy of poor hardware. Low quality hardware’s behavior is more difficult to predict and control. This is obviously a non-sustainable and wild approach but, unfortunately, there are no global regulations and no enforceable actions that can prevent these behaviors.

Third, some of the experts argue that, although many actors can access space and place their objects into space due to the lowered cost to launch, only a select few actors—those with superior information processing capability—will see any benefit from more affordable access to the space domain. Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation suggests that when “anyone on the planet with a few dollars will be able to get raw data” from space-based assets, the key “differentiation then is going to be in analysis,” and the benefits of affordable launch services will mostly accrue to those actors who will be able to “look at that data and say, ‘That is a T-72, and that is an M-1 Abrams’ or ‘That is an American AEGIS destroyer, and that is a South Korean or Chinese destroyer.’”

Fourth, and finally, Dr. Davis hypothesizes that a critical national implication of affordable launch capabilities will emerge with the “development of reusable launch capabilities—reusable rockets, airborne launch, and, on the horizon, aerospace planes,” because these technological developments could “improve responsiveness and boost cost efficiencies in accessing and exploiting space” in ways that could “fundamentally transform military space operations.”

Conclusion

In conclusion, the main national security effect of reduced cost to launch is that cheaper launches enable a greater number of actors to send a wider range of payloads—some of which will, quite frankly, be junk—into space. Cheaper costs to launch also shape how countries leverage (and build) their national space programs by shifting available procurement patterns.

Contributors

Roberto Aceti (OHB Italia S.p.A, Italy); Adranos Energetics; Brett Alexander (Blue Origin); Major General (USAF ret.) James B. Armor, Jr.2 (Orbital ATK); Mark Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Dr. Riccardo Bevilacqua3 (University of Florida); Caelus Partners, LLC; Elliot Carol4 (Ripple Aerospace, Norway); Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy); Dr. Malcolm Ronald Davis (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Australia); Faulconer Consulting Group; Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson (United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Harris Corporation, LLC; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, University of Maryland); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Dr. John Karpiscak III (United States Army Geospatial Center); Group Captain (Indian Air Force ret.) Ajey Lele5 (Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, India); Dr. Martin Lindsey (United States Pacific Command); Dr. George C. Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Jim Norman (NASA); Dr. Deganit Paikowsky (Tel Aviv University, Israel); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Dr. Patrick A. Stadter (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory); Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; John Thornton (Astrobotic Technology); ViaSat, Inc.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q19] What international legal codes or norms are needed to govern the increasingly crowded space domain?

[Q23] Fifty years of space has seen much change. Which aspects of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 are still valid and which need updating? Is it better to add to/amend the 1967 Treaty or to establish a new framework for the 21st century?

Author: Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) is the lynchpin of the current international legal regime for space. 105 countries have ratified the treaty, while another 25 are signatories.6 The OST extends the UN Charter and its underlying principles to outer space (Berkowitz), and provides additional principles to guide activities in space. These principles have been elaborated and further codified in three subsequent UN treaties related to space activity: the 1968 Rescue Agreement, 1972 Liability Convention, and 1975 Registration Convention.

OST: Retain, Amend, Replace?

The OST and the other “core” treaties were drafted in a relatively short time in the late 1960’s to mid-1970s. The principles upon which they rest—peaceful use of space, free access, and non-territoriality—clearly reflect a shared contemporary concern that Cold War competition could spill over into space. Today, these principles can often be found at the center of arguments that the OST is obsolete, or at least in need of amendment.

However, when asked whether they thought the OST should be amended or replaced, a large majority of the contributors (see Figure 1) respond that the treaty should not be changed at all. Furthermore, contributors who favor amendment specified changes that are limited in scope, rather than a more comprehensive revision of the treaty.8 As Figure 2 shows, opinion does vary between different groups of expert contributors. Academics overwhelmingly favor keeping the OST without change, while the majority of contributors representing commercial enterprises favor amendment or replacement.,

OST: Comprehensive Law or Guiding Principles?

The division in opinion over whether to keep the OST unchanged, or amend or replace it, appears to derive primarily from how the contributors conceptualize the role of the OST in space governance. Those favoring amendment or replacement appear to be considering the OST as a stand-alone and independently comprehensive legal document. In light of the enormous changes in the actors involved in the space domain, this perspective leads them to conclude that the OST cannot provide the legal structure necessary for ensuring the development of either commercial space, or the national security interests of the US in space.

In contrast, those who oppose changing the OST consider it as a set of guiding principles for governing space, rather than a comprehensive set of regulations. David Koplow of the Georgetown University Law Center, Dr. Cassandra Steer of Women in International Security-Canada, and Dr. Brian Weeden of the Secure World Foundation compare its role to that of the US constitution. In a similar vein, Dr. Mark J. Sundahl of the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law and Koplow evoke the Magna Carta. However, as Koplow notes,9 just as statements of foundational principles are insufficient to govern a state, they are also insufficient to govern space.

It’s as if, in the case of the United States, we had adopted the Constitution, but then Congress did not get around to passing any laws after. The Constitution sets out the general principles, but you have to flesh those out.

Understood in this light, the continued relevance of the OST is not a function of whether it can address all contingencies and legal requirements for current and future activities in space. Rather, what matters is whether it provides an operative framework for creating subsidiary treaties, agreements, and norms to regulate activities in space. Those who support the continuation of the OST unchanged, judge it to be capable of doing this (Armor; Blount; Gabrynowicz; Gallagher; Hitchens; Johnson; Meyer; Steer; Sundahl). Furthermore, they state, it has been successful; enabling safe and secure access to space (Gabrynowicz; Meyer; Sundahl), blocking the placement of nuclear weapons in space (Gabrynowicz; Sundahl), and preventing national appropriation of the Moon or other celestial bodies (Sundahl). This success has, in turn, given the OST a level of legitimacy and influence that would be difficult to recreate in a new treaty. Christopher Johnson of the Secure World Foundation concludes:

This demonstrates that, rather than the treaty showing its age after fifty years, this long- standing treaty has facilitated five decades of the peaceful and profitable uses of the access, exploration, and use of outer space, and that states respect and observe the treaty.

Arguments for Leaving the OST Alone

Supporters of the OST in its current form tend to see amendment (and even more so replacement) not only as unnecessary but as potentially perilous as well. They do not take this position out of a belief that there is no need to further develop international space law and norms. In fact, all identify very similar areas of activity that need further codification to those presented by the contributors who argue that the OST should be amended or replaced. Rather, their concerns arise from the potential threat to the legitimacy and support for existing space law, more generally, that changes to the OST could trigger.

Several argue that if the OST were opened to amendment, the process may be difficult to control,10 as amending one section of the treaty would put other sections “on the table” as well (Hertzfeld). This, as Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor of Orbital OTK puts it, may “encourage mischief” and be counter to US interests. Similarly, Joanne Gabrynowicz of the University of Mississippi School of Law and an Anonymous Contributor11 see opening the OST as inviting the potential loss of the prohibition on nuclear weapons and WMD in space. Although not in favor of altering the OST, Paul Meyer of Simon Fraser University notes12 that some see a potential for supplementing the OST without running the risks of opening up the treaty text itself. In multilateral diplomacy this is often accomplished through developing an "Optional Protocol" that can supplement the original treaty in some way (e.g., extend the ban on WMD to all space-based weapons, or provide for the type of institutional support such as annual meetings of states parties that is common now but which the OST lacks).

The OST has Provided a Durable Set of Principles

As Steer argues, recent negotiations over new legal codes for space, which have stalemated over key national security concerns,13 should serve as a warning that the fundamental principles of the OST are not necessarily undisputed. Is this not an argument for amendment or replacement? Not according to a number of the contributors who provided input for this report.

When the OST and three core treaties were negotiated, there were only two nations active in space, and less than 20 members of the Committee on the Peaceful Use of Outer Space (COPUOS). There are now 85 members, as well as many countries with assets in space and a quickly expanding set of commercial space actors (Hertzfeld; Simpson; Steer). Given the current international and space environments, contributors are doubtful that a new or significantly amended treaty could reach greater consensus than the OST (Anonymous Contributor; von der Dunk), and any new treaty is expected to take years, even decades, to complete, if it is at all (Anonymous Contributor; Armor; Hertzfeld). During this time, as an Anonymous Contributor notes, “new customary international rules” for space may emerge14 that may not work or serve US interests as well as the current treaty (Blount; Gallagher). That is to say, simply engaging in the process of renegotiation could undermine the authority the OST by creating competing principles for actions in space. Meyer makes an important point regarding the influence of the OST over the past 50 years:

We are repeatedly told that space is ‘congested, competitive, and contested’ but not reminded that it has been a realm of remarkable international ‘cooperation’ as well. The Outer Space Treaty embodied this cooperative approach.

Spillover Effect

Steer notes that the key “principles and clauses are today considered to be customary international law, thus binding on all states, regardless of whether they are party to the OST or not.” When considered in conjunction with the observation of Dr. P.J. Blount of the University of Luxembourg, that “there is a regime of treaties and UNGA resolutions that elaborate on particular aspects of the Outer Space Treaty, and there is a growing body of domestic law and policy that reveals how states are interpreting ambiguities in the treaty,” the broader implications of amending or replacing the OST become clearer. If the legal regime in space is indeed rooted in the OST, then any changes to the substance or standing of the treaty would spillover to affect other legal codes for space.

Governance in Space

As noted above, regardless of their position on the OST (amend, replace, retain), when asked what changes to international legal codes or norms are needed to govern the increasingly crowded space domain, contributors raise a fairly consistent list of issues. Nevertheless, differences of opinion and interpretation do emerge.

State-Centrism of Current Codes

Dr. Henry Hertzfeld of George Washington University sees the state-centric focus of existing legal codes as problematic given the rapid increase in the number of non-state actors involved in space activities. He suggests that while “[t]echnically, nations are responsible for their activities in outer space and even liable for them,” there is “a whole set of commercial law that is not that precisely defined for space.” Relatedly, Steer notes that the rise to prominence of commercial space actors was “either not foreseen by the drafters of the OST, or, given the political pressures at the time, simply not a priority.”15 As a result, many contributors identify commercial space activities as an area in which clearer legal codes and regulations are needed. Differences of opinion involve whether commercial activities can be accommodated within the OST in its present form. Dr. Frans von der Dunk of the University of Nebraska College of Law and Armor believe that they can. Among those who think not, Jonathan Fox of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency and contributors from Faulconer Consulting Group point to Article VI16 of the OST in particular as needing “to be substantially modified to provide protection of space- related commercial rights arising in the coming years” (Fox).

Barriers to Commercial Development

As space actors are diversifying, so are the activities in which they engage. Article II and the non- appropriation principle17 have been the focus of arguments that the OST stands in the way of commercial development in outer space (Blount). Article II is seen to present significant barriers to commercial actors and investors operating beyond Earth (space tourism, space hotels) (Cheng), as well as those interested in developing space mining (Faulconer Consulting Group; Fox). Fox contends that, as it stands, the OST prevents “legitimate exercise of market-based commercial activities (including natural resource mining, refining, exploration, extraction, transportation, and other related functions) as may safely and practicably be undertaken under the license and authority of space-faring nations, in accordance with their applicable laws.”

Countering this, Armor notes: “the recent [US] Commercial Launch Competitiveness Act allowed ‘ownership’ of resources removed from planetary bodies. It does not violate the OST at all but clarifies commercial exploitation consistent with original intent of the Treaty.”18 Weeden agrees that there is a lack of clarity in the existing principle but notes that lawyers and economists have used fishing laws as a potential model which would enable resource extraction and use without requiring territorial ownership. This view is shared by Blount, who sees the implications of such changes as far-reaching and potentially detrimental to the United States’ national security interests:

It would be foolish to discard a foundational security treaty that helps to maintain international peace over the question of property rights...While the Outer Space Treaty may increase the cost of doing business for commercial operators, their investments would not be safe without such a treaty.

Governance of Space Debris and Traffic

As the space domain becomes more crowded the need for regulation to protect assets and valuable orbits has become apparent if space is to remain sustainable (Sundahl). Space debris is in many ways a classic collective action problem—it creates potential risk to every space actor, if not addressed it could ultimately render space unsafe for all, and it cannot be “solved” without cooperation between most or all space actors.

Orbital debris guidelines, such as those developed by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), have been effective but need to be updated to account for new capabilities, such as large constellations of satellites (Spire Global Inc.). While Steer notes that these guidelines have generated “a very high level of compliance,” Dr. Luca Rossettini of D-Orbit and contributors from Spire Global Inc. argue that binding rules and some enforcement mechanism are required. Matthew Schaefer of the University of Nebraska College of Law notes, however, that ownership issues may create a problem here. Specifically, whether objects owned by another actor can legally be removed without the owner’s consent.

Space traffic is also seen by the contributors to be an area in which the need for better regulation is becoming more pressing, as it threatens the collective interest of all space actors in the long-term (Steer; Sundahl; Weeden). Commercial plans for satellite servicing, refueling, and outer-orbit inspections will involve getting close to and docking with satellites (Weeden), and Rossettini argues that regulation and clear norms need to be created “to ensure the use of space becomes a controllable or at least verifiable.”

Surveillance and Irresponsible Behavior

Traffic and proximity issues also raise national security concerns. Sundahl and Weeden both give the example of a state actor flying satellites close to those of an adversary. As Weeden ponders:

What is the space equivalent of an Incidents at Sea Agreement that is going to kind of give a bright line of ‘you should do this, this is how you behave responsibly, and this is how we do it normally,’ and if there is deviation from that, it suddenly becomes an indication or warning that something is not right.

Without agreed upon norms of behavior, the potential exists for either unintended escalation or loss of security. To this point, Steer suggests further development of data sharing and transparency norms. This approach is consistent with discussions by Tanja Masson-Zwaan of Leiden University, Dr. Nancy Gallagher of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, and Johnson, and reflects the assessment of Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin that there is a need to strengthen mechanisms for consultation, crisis management, and dispute resolution.

Bottom Line

Regardless of their stance on the OST, all of the contributors see existing space law and norms as insufficient to manage the rapidly evolving nature of space activities, and the current and potential threats these activities present. As space becomes more crowded, the risk of accidental or intentional harm to an actor’s assets increases. And, as space capabilities become more critical to actors, the cost of losing those assets also increases. Both of these conditions create a collective action problem that the further articulation of international norms and regulation could potentially mitigate for all. However, most contributors do not think that amending or replacing the OST is either necessary or advisable. These contributors warn that opening up the OST would likely trigger a long and uncontrollable process of negotiation that in itself would create uncertainty and undermine the legitimacy of the OST. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that the final treaty would work as well, let alone any better.

Contributors

Anonymous Contributor;2 Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor3 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Dr. P.J. Blount (University of Luxembourg); Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Faulconer Consulting Group; Jonathan D. Fox (Defense Threat Reduction Agency Global Futures Office); Joanne Gabrynowicz (University of Mississippi School of Law); Dr. Nancy Gallagher (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Dr. Peter L. Hays (George Washington University); Dr. Henry R. Hertzfeld (George Washington University); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Christopher Johnson (Secure World Foundation); Group Captain (Indian Air Force ret.) Ajey Lele4 (Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, India); David Koplow (Georgetown University Law Center); Tanja Masson-Zwaan (Leiden University, Netherlands); Paul Meyer (Simon Fraser University, Canada); Dr. George Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Michiru Nishida5 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Japan); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D- Orbit, Italy); Matthew Schaefer and Jack M. Beard (University of Nebraska College of Law); Dr. Michael K. Simpson (Secure World Foundation); Spire Global Inc.; Dr. Cassandra Steer (Women in International Security-Canada, Canada); Dr. Mark J. Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); Anne Sweet (NASA); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska College of Law); Dr. Brian Weeden (Secure World Foundation)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Question (R6.10): What can the U.S. and Coalition partners realistically do to enable Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) to combat a long-term ISIS insurgency? Recognizing the enormous resources the U.S. poured into the ISF from 2003 until 2011, only to see much of the force collapse in 2014, what can we do to avoid making the same mistakes when training the ISF?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

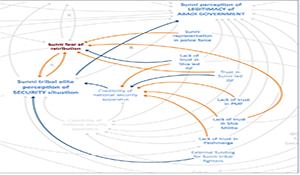

At the beginning of the Reach Back effort in 2016, Drs. Belinda Bragg and Sabrina Pagano from NSI Inc. created a qualitative loop diagram1 of security dynamics representing Kurdish, Shia, and Sunni populations in Iraq using NSI’s Stability Model (StaM).2 They found that security dynamics in the region were driven in large part by perceptions of social accord and governing legitimacy. These findings apply today to the study of why Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) failed in 2014, why they are strengthening today, and what pitfalls they may face in the future.

Iraq’s Sunni Arabs have voiced fears that, once areas of Iraq controlled by ISIL have been liberated, Kurdish and Shia Iraqis will seek to exact retribution against Sunni populations in these areas for the actions carried out by ISIL (Amnesty International, 2016; Fahim, 2016; Hauslohner & Cunningham, 2014; Rozen, 2016). “There are many barriers [to Sunni IDP’s WHAT CAN CENTCOM DO? Decreasing Sunni fear of retribu-on In Iraq there are a mul-tude of military and paramilitary groups and organiza-ons, with various levels of allegiance to and control by the central government. At present, they are at least loosely upeople accused—rightluynity or wrongly—of complicity and lack of coordination among local strongly iden-fied sectarian mili-a is likely to significantly reduce percep-ons of security and increase the likelihood of sectarian violence reemerging. authorities and security forces” (United States Institute of Peace Staff, 2016). (Bragg & Pagano, Specifically as this sec-on of the loop diagram below illustrates, the nature of the various military and paramilitary forces present in Iraq contributes significantly to Sunni fear of reprisals. Human SOCIAL Sunni sense of r i g h t2s a0b u1s e6s )

The loop diagram in Figure 1 suggests Sunni percep-on of equality R Sunni fear of retribu.on R Sunni tribal elite percep.on of SECURITY situa.on Sunni percep.on of LEGITIMACY of ABADI GOVERNMENT Lack of trust Corrup-on & patronage Sunni Ideological radicalism (New ISIL) Equal administra-on of rule of law & jus-ce GOVERNING CAPACITY Local / na.onal among Sunni, Shia, Kurd Sunni sense of to enhance Sunni perception of the aliena-on from Shia-led government’s legitimacy, Sunni government Cross-represectnaritaan ltanidon in the police become an Sunni representa-on in police force Lack of trust in Shia led ISF essential part of the professionalization disputes Sunni Sa-sfac-on with resource R Credibility of na-onal security apparatus of the ISF going forward (Bragg & quality ofmdistribu-on process & life Pagano, 2016). Failure to do so may turn Sunni populations, particularly in areas where ISF forces must operate in Ability / willingness of Sunni IDPs/refugees to return the fight against Daesh, against them (Hamasaeed, Kaltenthaler). However, as this type of analysis shows, there is also a “virtuous” loop where in crease Sunni perception of equality enhances perceptions of legitimacy, which enhances security, which ultimately enhances a sense of fair political representation (Bragg & Pagano, 2016). This loop highlights the centrality of political and social factors to the potential for stability and security in Iraq moving forward, which is also supported by Mr. Hamasaeed.

By updating the loop diagram to focus primarily on the role and function of the ISF, we can get beyond a list of the sources of failure and potential solutions to get at the heart of the problem: large segments of Iraq’s population (primarily Sunni Arabs and Kurds) do not trust the government, and by extension, the ISF. Where there is no trust, there can be no legitimacy.3 A government that protects the interests of Shia over Sunnis results in institutions, like the armed forces, that promulgate a negative feedback loop where the unwillingness of forces to protect Sunnis erodes Sunni trust in the government, resulting in the ISF being perceived as an illegitimate and ineffective force.

Experts note that ISF has made marked improvement in combating Da’esh over the last year (Liebl, Whiteside). They point to a new sense of nationalism among the citizens of Iraq and the ISF in the face of an adversary that has come to be seen as an existential threat. However, it begs the question of what will happen when the threat that has unified the country to some degree recedes. It also raises concern that while the population on average may experience rising nationalism, specific groups may not share in that experience, which can lead to unrest that affects the country. This is even more pertinent as ISF chases the remnants of Daesh fighters to rural, Sunni dominated areas with a military force led and comprised primarily of Shia personnel.