SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Question (R6.2): In the event that the US/Coalition is challenged by another global power [Russia for the purposes of this response], what are the second and third order effects in the USCENTCOM area of responsibility?

Author | Editor: Jafri, A. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

As Russia continues to challenge United States’ power and influence around the world, its activities in CENTCOM’s area of responsibility (AOR) represent a useful lens with which to view this conflict. In Iraq and Syria, both Russia and the United States (and its Coalition) have been drawn into this layered conflict to challenge or defend the status quo with varying degrees of success and impact. While experts question whether Russia can challenge the United States globally, it can likely operate on the margins of United States interests, with a series of surgical and lower-level policy decisions. To that point, some respondents, including Edward Chow of the Center for Strategic and International Studies and Vern Liebl of the Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning at Marine Corps University, argue that they do not consider Russia a true peer and challenger of US global influence. Instead of global dominance, Russia is seeking to “marginalize US power and influence in regions they deem important to their interests” (Chow). Contributors agreed, though, that Russia is well positioned to capitalize on opportunities for growth and influence in the Middle East. This report looks at Russia’s interests, actions, and likelihood of success in challenging US global influence through these conflicts.

Conditions Favoring Increased Russian Influence

In order to better understand the opportunities available to Russia in CENTCOM’s AOR, experts provided context on the current situation in the region. Dr. Spencer Meredith III of the National Defense University’s College of International and Security Affairs took note of how Russian opportunism has taken advantage of an environment that allows them to exert outsized influence on events in the CENTCOM AOR. Mr. Liebl noted that Russia is “winning” in the information operations domain, particularly as they have widely publicized successful humanitarian initiatives, specifically the effective missions by Russian Explosive Ordinance Detail (EOD) teams that have benefitted Syrian citizens. According to Dr. Abdulaziz Sager of the Gulf Research Center, this along with other recent Russian activities has afforded them greater credibility among more states in the region. This is reinforced by the successful continuation of a narrative that paints the United States as a regional destabilizer (Meredith). In Liebl’s estimation, this success has been made possible by US forfeiture of the regional narrative space, which is accompanied by waning American influence, wavering commitments, and relinquishing leadership.

This environment of waning influence has also been influenced by what is seen as wavering commitment on the part of domestic policymakers in the United States according to both Dr. Frederick Kagan and Ms. Katherine Zimmerman of the American Enterprise Institute. They concede the possibility that domestic public opinion could swing towards wanting to partner with Russia instead of countering them in the area. Experts have also argued that the US has abandoned its leadership role in the Middle East. Specifically, in negotiations related to Syria, Libya, and Yemen, Dr. Kagan and Ms. Zimmerman note that the United States has not been leading the process. The current environment of sliding US leadership and subsequent Russian usurpation could have consequences stretching across a number of domains.

Effects of Russia Achieving its Objectives in the Middle East on US Strategy and Interests

Military

Mr. Chow argues that the Russian military seeks to diminish US military capabilities in the region. This would be achieved by maintaining their current bases, but also by expanding their operational footprint into Iran, among other states (Chow). Any actions aligned towards this objective could threaten US assets and limit US freedom of movement—an interest that the United States would seek to protect (Kagan, Zimmerman). Russia has worked to be perceived as a reliable partner, which might make states in the region more willing to allow Russia to base facilities and operations within their jurisdictions, according to Dr. Sager. Additionally, Russia is likely to bolster arms sales to regional actors (Sager, Kagan, Zimmerman). Dr. Sager notes that the cost difference between Russian and American systems, as well as the lack of strings attached to Russian purchases privileges the Russian Federation in this arena. Additionally, skepticism by Gulf States of the United States’ commitment to the region has led some countries in the region to hedge their bets and seek deepened relationships with Russia (Kagan, Zimmerman).

Energy

A primary arena in which Russia is well positioned to capitalize on fluid regional dynamics is in global energy markets. Both Chow’s and the Kagan-Zimmerman responses suggested that Russia would seek to develop closer relations with Saudi Arabia (and other oil producing states). Such a Russian move could decrease US leverage in Saudi Arabia (Kagan, Zimmerman). Additionally, while this may complicate US economic interests, it may also produce an opportunity for the United States to work with other large oil-consuming states, such as China and India in a context that reflects the common interests that these states share (Chow). Looking beyond Saudi Arabia, increased Russian activity in other regional energy markets (such as Libya) could imperil certain European energy markets, such as Italy (Kagan, Zimmerman). The competitive regional energy landscape has prevented such Russian activities from becoming an inevitability, but they do remain a possibility.

Both the South Stream and the (planned) TurkStream pipelines also represent a major inflection point in the region’s power dynamics. If Russia is to capitalize on the market access that the TurkStream pipeline would provide, it could decide to mitigate the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in order to appease Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Meredith). Similarly, the TurkStream pipeline offers an opportunity for Russia to strengthen its hand in the region. This pipeline provides an alternative route to European markets that circumvents Ukraine, and any political pitfalls therein. It also opens up a new front of market vulnerability for the European Union, who will be subject to a fickle Russia as an energy gatekeeper, although US LNG can mitigate this (Meredith). This pipeline would have the dual impact of deepening Russo-Turkish relations, while also motivating Iran to seek a closer relationship with Russia to deepen their energy partnership (Meredith). A renewed Russo-Turkish relationship could also prompt those countries to support each other in projects away from this region.

International Diplomacy

Russia stands to make international diplomatic gains in the new environment discussed above. In the aftermath of the Iraqi state’s campaign against Da’esh, there remain opportunities for Russia to help stabilize political and security events in the country (Chow). Additionally, through initiatives supporting international negotiations, Russia could create alternative fora that run parallel to the United Nations and other Western-oriented organizations (Kagan, Zimmerman). Indeed the diplomatic vacuum mentioned by Dr. Kagan and Ms. Zimmerman serves as an inducement to Russian behavior in this arena and persists despite local wariness of Russian involvement and regional states’ lack of conviction of the viability and benefits of a long-term relationship with Russia. Additionally, Russia may also be constrained by limited diplomatic resources that would prevent them from involvement in a large number of different initiatives (Kagan, Zimmerman). Russia may also seek to seize the mantle of combating global terrorism and fighting global jihadist movements (Chow). This also reflects concurrent domestic Russian priorities in Chechnya and elsewhere (Liebl).

The current situation in the CENTCOM AOR also provides challenges and opportunities for Russia as it considers its bilateral relationships there. Egypt has allowed Russian military aircraft to use Egyptian bases and airspace. While this represents an opportunity for Russia, it is part of a longstanding Egyptian strategy of playing the United States and the Russians (and previously the USSR) against one another (Liebl). In Syria, Russian interests include the preservation of the Assad regime. To that end, they are leading peace talks on their terms (Liebl). Complicating a potential US response is the notion that Russian activities have been more effective in Syria than those undertaken by the United States (Sager). Similar to the Egyptian strategy of balancing Russian and American interests against each other, Iraq is playing a similar game (Liebl). Indeed, Russia has the ability to play a significant part in reconstruction efforts in Iraq, a role that they will likely relish (Kagan, Zimmerman).

The burgeoning Russo-Turkish relationship has been mentioned earlier in the context of energy cooperation. Despite historical competition between those two entities, the current fraught relationship between Turkey and the United States presents an opportunity for Russia to move in (Kagan, Zimmerman). This potential rapprochement will embolden Turkey (and perhaps even Iran) to subdue Kurdish self-determination efforts (Meredith). Iran’s standing distrust of the current US Administration is a potential opening for further improving relations with Russia buttressed by Russian and Iranian convergent interests in containing the opium trade in Afghanistan (Liebl). If Russia does indeed challenge the United States’ strategic imperatives, Iran could be drawn in as well, prompting a likely response from Gulf countries wary of increased Iranian activity in the neighborhood, according to regional expert Mubin Shaikh.

Conclusion

According to Dr. Meredith and Dr. Sager, Russia will be one of several—if not the leading—actors shaping and defining the outcome of conflicts in the central Middle East. These efforts will ensure an enduring Russian presence in the region in terms of military operations and economic trade (Meredith). While the US can do little to halt Russia’s expanding influence in the region, the US could attempt to at the very least, maintain, if not increase, its influence, resulting in a period of “enduring competition.” Even maintaining its current level of influence is challenging though, given Russian advances in the region. Dr. Meredith argues, “The loss of US reputation in the region is inevitable” in part because the natural, historical (and conflicting) interests of regional actors are reemerging—they no longer need or want the US to set the terms, the conditions for success, or most of all, constrain their independent actions. This is in part due to the “success” of US regional capacity building efforts over the years, as much as their own initiative. Dr. Meredith concludes that Russia’s likely entrenchment and success in the Middle East will result in the return of the “’great game’ of power politics with fluid allegiances, amidst fixed interests, all centered on relative gains in a zero-sum international environment.”

Contributors

Mr. Edward Chow, Center for Strategic and International Studies; Dr. Frederick Kagan, American Enterprise Institute; Mr. Vern Liebl, Center for Advanced Operational Cultural Learning, USMC University; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Mr. Mubin Shaikh, Independent Consultant; Ms. Katherine Zimmerman, American Enterprise Institute

Blame, Sway, and Vigilante Tactics: How Other Cultures Think Differently and Implications for Planning.

Author | Editor: G. Sutherlin (Geographic Services, Inc.).

Executive Summary

Planners require context in order to achieve their goals. While planners understand that colder or more elevated locations have implications for an operation, the capacity to similarly adapt plans and operations based on differences in the population’s cultural or cognitive attributes has not been as readily integrated. The purpose of this SMA White Paper is to synthesize ideas across cognitive science and applied social science and translate their application for use in operations and planning within the span of a single document. The contributors each look at distinct cognitive functions that merit attention. By translating or operationalizing the research and discussing it in terms of real-world scenarios, this paper illustrates how the addition of cultural cognitive diversity research will enable more effective, quick, less violent, and less expensive operations.

Contributors

LTC Xavier Colon (5th BN, 1st SWTG(A)), Dr. Rose Hendricks (University of California, San Diego), Dr. Anatoliy Kharkhurin (American University Sharjah), Brig. Tim Lai (British Army), SFC Matthew Martin (5th MISB(A)), Dr. Abdul-Akeem Sadiq (University of Central Florida), Dr. Moritz Schuberth (Mercy Corps), Dr. Gwyneth Sutherlin (Geographic Services, Inc.), Ms. Jenna Tyler (University of Central Florida)

Question (R6.4): Knowing that religion is only one (and not the most important) stimulus for disgruntled Islamic youth to join VEOs, what could/should be the domestic messaging to youth to prevent their “radicalization” and joining the VEOs? To what extent could a continued presence of Western military in the Middle East (even only as instructors/trainers) undermine this messaging in the region?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

After the fall of Mosul, as it became clear that Daesh could no longer creditably claim broad swaths of territory for its caliphate, it deliberately reverted to a strategy of insurgency, according to Syrian expert Hassan Hassan.1 Its withdrawal into the rural desert landscape—and to what a radicalization expert, Haroon Ulla, calls the “cloud caliphate”2—has implications for counter-radicalization messaging. Hassan reminds us that when the organization was defeated in the late 2000s, it came back stronger than ever. He notes that its messaging has recently pivoted to attempts to erode trust between Sunni Arab populations and any form of legitimate government. Daesh’s messaging is fueled by the recent memory of the failure of the Sahwa (or Awakening) movement to produce meaningful political reforms for Sunni populations in Iraq. In Syria, Daesh still benefits from the ongoing conflict and enduring Sunni Muslim grievances. At the same time, hardened foreign fighters are leaving Syria and Iraq for other regions where extremism is flourishing including the Sinai region of Egypt and Yemen (Hassan). And, of course, some foreign fighters are returning home across the globe where they can be incubators of future generations of extremists (Hassan).

So given Daesh’s return to insurgency and its embrace of information age recruitment techniques, what are the grievances3 driving the radicalization of youth in Iraq and Syria, and what messages would be effective in tarnishing the appeal of extremism? It bears repeating that effective counter extremism messaging in Iraq and Syria requires state and local governments to match promises of reform with actual reform (Kluver, Sager). Dr. Sager reminds readers that between 2007 and 2009, Daesh disappeared from Iraq as the result of the Sahwa movement. But once promised political reform failed to actualize, Daesh came back. This failure of reform cemented the conclusion that the only way to enact reform is through violence. As Hassan notes, Daesh has already begun sowing doubt along these lines.

What is concerning to Dr. Ian McCulloh, a social science researcher and proponent of field research/population surveys, is that the USG has yet to realize that the remaining population of military aged males in Iraq—those most vulnerable to a new round of recruitment from Daesh, Al Qaeda, or other groups—has been stripped of its hard-core ideologues. Those who have not been killed, captured, or fled are likely to be poor, illiterate, and have limited access to social media. These factors may indicate that social media campaigns will have limited effect on this kind of population.

So if the most effective counter radicalization tool is visible political reform, the primary role for the US in counter extremism messaging is a supporting one encouraging regional governments to make meaningful reforms that address the driving forces7 of radicalization among marginalized Sunni groups (Kluver, Sager). When the USG engages in messaging, it should focus on 1) legitimizing government partners, 2) promoting economic development and regional stability, 3) supporting foreign aid, and 4) reinforcing cultural norms (Sager). For a discussion on how to undermine Daesh’s leadership, please see Dr. Gina Ligon’s article Leveraging Organizational Fissures to Degrade ISIL Top Management Team in the contribution section.

While a foreign military presence may be deemed necessary for a short time, contributors believe US military presence generally fuels radicalization narratives (Styszynski). Dr. Sager emphasized that in order to avoid undermining counter-radicalization messages with the presence of Western forces, the US should be seen as a catalyst for genuine political reform that benefits populations most at risk of radicalization: Sunni Arabs. The USG should exercise caution, however, to not take adopt general guidelines without further critical analysis, according to Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois of NSI. If, for example, hardliners win Parliamentary elections in Iraq, visible US support for an administration that is viewed by many Sunni Arab Iraqi as opposed to their interests could fuel further political marginalization, alienation, and radicalization.

Contributors

Ms. Alyssa Adamson, Oklahoma State University; Dr. Skye Cooley, Oklahoma State University; Mr. Hassan Hassan, Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy; Dr. Robert Hinck, Monmouth College; Dr. Randy Kluver, Oklahoma State University; Dr. Gina Ligon, University of Nebraska, Omaha; Dr. Ian McCulloh, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, University of London (UK); Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Mubin Shaikh, Independent Expert; Dr. Ethan Stokes, University of Alabama; Dr. Marcin Styszynski, Adam Mickiewicz University (Poland); Dr. Haroon Ullah, Broadcast Board of Governors

Question (R6.1): What conditions (demographic, political, etc.) should exist on the ground in the Middle Euphrates River Valley and the tri border (Syria/Jordan/Iraq) region to deny the seeds of future conflict from being planted – particularly taking into account the assumed intention of Iranian proxy forces to establish a Shia “land bridge?” Which of these conditions can and should be insisted on as part of a Geneva peace process to end the current conflict in Syria?

Author | Editor: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

Ambassador James Dobbins and a team from the RAND Corporation contend, “the Syria civil war is approaching, if not a conclusion, at least a hiatus that might be converted into a conclusion.”1 Major regional players—United States, Russia, and NATO—have a converging interest in ending the conflict and facilitating a stable peace, Dr. Amir Bagherpour of giStrat argues. However, despite an emerging shared preference between Russia and the United States on ending the conflict in Syria, rivalry dynamics between Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Qatar, and the UAE will likely have a dampening effect on peace prospects as the proxy warfare intensifies following the military defeat of Da’esh. Mr. Hassan Hassan of Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy warns that the worsening of the various conflicts in the region is still a serious possibility.

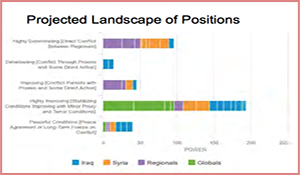

As the fight against Da’esh winds down in Iraq and Syria, brewing tensions and conflicts between regional actors and proxy groups is gaining new momentum. We asked thirteen regional experts to identify the top conditions necessary to bring an end to conflict in the region as well as effect a stable peace. Figure 1 captures several thematic categories of conditions posited by the authors in rank order as well as the estimated likelihood of occurrence.

Reduction in Proxy Forces

GiStrat’s computational modeling found that “the most significant factor for creating stabilizing conditions in the Euphrates River Valley is a reduction in proxy support by opposing larger powers,” a condition that seven other contributors agree is an essential criterion. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, Russia, and the United States all support or fund proxy forces, but several experts emphasize Iranian proxy operations as the primary aggravating obstacle to peace in the region (Cafarella, Ganor, Jeffrey). Mr. Mubin Shaikh,3 an extremism expert, and Dr. Abdulaziz Sager of the Gulf Research Center both write that undermining pro-Iranian militias are the key to disrupting the Shia crescent “land bridge,” which Shaikh argues already effectively exists across Iraq and Syria.

Removal of Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs)

The removal of Da’esh and Al-Qaeda in Iraq and Syria is mentioned by three authors4 who distinguish these groups from other proxy forces in the region. Dr. Martin Styszynski of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland argues that the “defeat of ISIS’ structures in Syria and failures or withdrawal of Islamist insurgents” has allowed for high-level consolidation of strategic territories between Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Ms. Jennifer Cafarella of the Institute for the Study of War views the removal of Sunni VEOs in the tri border region as fueling the Assad regime’s advantage over the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and weakening the likelihood of Assad to negotiate. Both contributors suggest that the demise of proxy groups and VEOs expose the underlying obstacles to a peace accord and the dormant mechanics of any future political settlements.

The Role of the Assad Regime in Peace

Contributors present a spectrum of possibilities on the fate of Assad’s continued leadership in the event of a lasting peace in Syria. One school of thought holds that regime change is absolutely necessary to a 2020 Geneva agreement (Ganor, Itani) while another holds a more moderate view that Assad will only need to exit at some point in the future (O’Shaughnessy, Yacoubian). The middle of the spectrum recognizes that the survival of the Assad regime is likely but his power will be constrained (Jeffrey) and concessions will be made to “opposition groups in Northern Syria, Southern Syria, and the Kurdish territory” (Bagherpour). The other extreme assumes that Assad has all but guaranteed a role in post- conflict Syria, that “the surrender of oppositions groups is certain,” and that Assad will emerge as victor (O’Shaughnessy).

Power Sharing and Territorial Concessions

The fluid and disparate landscape in the triorder region understandingly necessitates a peace process that will be predicated on numerous, multivariate resolutions where stakeholders concede a significant amount of geopolitical capital. Almost all of these concessions described by contributors involve dyadic relationships and are comprised of territorial cessation, decentralizing political governance, or military mobilization/de-escalation. Mr. Faysal Itani of the Atlantic Council lists a territorial partition as absolutely essential to peace while Ms. Cafarella contends that de-escalation zones (as a precursor to a peace agreement) do not honor their political or humanitarian purpose and only make the Syrian regime less likely to negotiate. There is also a particular emphasis on Russia committing to a “de-prioritization of the Middle Eastern Theater” (Cafarella) and the Turkey/SDF conflict reaching some sort of armistice.

Ms. Mona Yacoubian of the United States Institute for Peace and Dr. Bagherpour contend that greater political autonomy for Sunni minorities in Iraq and ultimately a significant devolution of power to governorates in Syria is a necessary condition for peace. Furthermore, Dr. Spencer Meredith III of National Defense University notes that the “SDF attaining a functional level of governance” is absolutely necessary for conflict resolution.5 Dr. Meredith also asserts that the US needs to advocate for strategic communication with Turkey on behalf of the SDF, whereas AMB Jeffrey takes this a step further and argues for a continued American military presence in Syria. AMB Dobbins and the RAND team similarly write of the usefulness of maintaining a US presence in counterbalancing Iranian in influence and providing leverage in negotiation over Syria’s longer-term future.

Socioeconomic Reconstruction

As political conventions for peace emerge, plans for the reconstruction of Syria must be correspondingly developed as well. Authors identified three mechanisms of socioeconomic advancement: micro-level community rehabilitation, reintegration, and humanitarian concerns. Both Ms. Yacoubian and the RAND team propose a bottom-up approach6 to development within and across communities to accompany an increase in decentralized governance. The RAND team and Dr. Ganor further articulate the importance of reintegrating refugees to forge economic activity and contribute to political participation in Syria. Ms. Cafarella notes the importance of creating mechanisms for DDR (disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration) and SSR (security sector reform) for former combatants.7 Basic humanitarian challenges are also of primary concern: specifically, the protection of minorities (e.g., Yazidis, Christians, etc.) (Bagherpour), the release of political prisoners and delivery of humanitarian aid (Cafarella), and the “continued monitoring of non-conventional material” (Ganor).

Contributors

Dr. Amir Bagherpour, giStrat; Ms. Jennifer Cafarella, Institute for the Study of War; Dr. Boaz Ganor, InterDisciplinary Center (Israel); Mr. Hassan Hassan, Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy; Mr. Faysal Itani, Atlantic Council; Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Alexander O’Donnell, giStrat; Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, University of London; Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Mr. Mubin Shaikh, Independent Analyst; Dr. Martin Styszynski, Adam Mickiewicz University; Ms. Mona Yacoubian, United States Institute of Peace

Question (R6.6): How does USCENTCOM, working within a whole of government approach, coordinate military operations in support of the change in approach towards Iran from the previous to the current administration?

Author | Editor: Jafri, A. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

As battlefield successes actualize, decision makers have an opportunity to align tactical and operational policies with a strategic vision. One year into a new presidential administration offers a window wherein actors on the ground can map their plans onto the tone, intent, and objectives of the new commander- in-chief. Despite some continuity between President Trump and his predecessor’s policies, particularly as related to Iran, there remain some significant differences. A wholesale White House-initiated change of approach vis-à-vis Iran has not yet occurred, despite these differences. If no substantive changes are made, CENTCOM is well positioned to build on established success in Iraq. However, if such a change were to occur, it would require a whole-of-government approach; within this framework, CENTCOM would be able to leverage capabilities built up over the course of their engagement in Iraq.

What is the Trump Approach?

Despite President Trump’s commitment to being seen as an abrogator of his predecessor’s policies, there remains some consistency in his policies vis-à-vis Iran. Dr. Abdulaziz Sager of the Gulf Research Center suggests that there is a lack of consensus around what exactly a novel Trump strategy would entail. He sees little daylight between Trump’s and Obama’s use of CENTCOM to contain Iranian influence. Similarly, Ambassador James Jeffrey of the Washington Institute on Near East Policy suggests that President Trump might follow a mixture of policies similar to those of the Obama Administration, i.e., primacy of nuclear issues (though Jeffrey concedes that whereas President Obama sought reconciliation on this point, President Trump has the opposite point of view), counterterrorism operations, and strengthening regional alliances. Despite the differences in approach to the Iranian nuclear issue, Jeffrey argues that insofar as President Obama labeled Iran a regional threat, there is little difference in rhetoric between Presidents Obama and Trump.

Moving beyond a boilerplate classification of Iran as a threat lays bare significant differences in the new administration’s strategy. According to AMB Jeffrey, the Trump administration perceives Iran as both a regional hegemon and ideological threat. This calculation exceeds the characterization that President Obama had for Iran. Similarly, Dr. Spencer Meredith III of National Defense University’s College of International and Security Affairs notes that the current administration perceives Iran as an expansionist power, hoping to recapture historical glory; he contrasts this with the Obama-era observation that Iran was guided more by internal politics than outward-looking objectives. This view is shared by Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, of the University of London, who suggests that President Trump’s view on Iran is characterized by distrust and antagonism. Despite that worldview, Dr. O’Shaughnessy writes that it is unlikely that President Trump would nullify the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). This view is also shared by AMB Jeffrey who is not convinced that the President’s domestic political allies are willing to pull out of the deal and institute a hard reset on relations with Iran.

A Whole of Government Approach

Despite near-consensus on the necessity of employing a whole-of-government approach if a strategic reset occurs, experts sought clarity on what precisely such an approach would actually entail (Jeffrey, Meredith). According to AMB Jeffrey, the approach taken since 2003 is not aligned with what appear to be the current Administration’s objectives, and suggests that policymakers strive for a clearly articulated approach similar to that employed during the Balkan Wars which specified a distinct political outcome followed by negotiations.

From a technical perspective, Dr. Meredith notes that capability specialization and clearly-defined policy documents bear the best results and suggests that the National Security Council serve as the primary coordinator of a multi-approach Iran policy. In addition to a “nation building” default, Ambassador Jeffrey suggests that apart from the JCPOA, negotiation skills at Foggy Bottom below the Secretary have dwindled. Similarly, Jeffrey argues, the Department of State today is not oriented towards incremental and measured progress working with multiple state actors.

CENTCOM Military Options in a Strategic Reset

There is not yet clarity as to whether or not the United States will commit to a full-scale strategic reset with Iran; such a move would be characterized by a major change in policy, such as the negation of the JCPOA. This lack of clarity makes military planning difficult (Sager).

Even if the current policy is not clarified further, there still exist some mission sets where CENTCOM is well equipped to succeed. AMB Jeffrey notes that the command has technical capabilities, relationships, and know-how to achieve its operational objectives in the region. Dr. Meredith notes that the mission of security force assistance, coordinated along clear lines of efforts, remains critical. He also noted the importance of engaging allies to help CENTCOM achieve its objectives in the region. Dr. O’Shaughnessy echoed this point, stressing the need for a pluralist policy, i.e., one wherein military and non-military entities are aligned on common goals. He notes that the most effective engagement with Iran happens in the diplomatic realm, and military capabilities can be best contextualized as force projection.

An alternative outcome is, as Dr. O’Shaughnessy proposed, an ostensible “cold war,” i.e., a situation typified by tough talk between adversaries, but with little changing below the harsher tone on the surface. This would prevent cooperation in areas of mutual interest between the United States and Iran, such as containing the spread of Da’esh into Afghanistan. On the other hand, O’Shaughnessy concedes, this situation would at least offers some measure of predictability, not just for policymakers, but CENTCOM as well. Experts did not anticipate a more conciliatory strategy; therefore, CENTCOM’s options in that context were not discussed.

Contributors

Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, University of London; Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center

[Q22] Can international agreements effectively protect high-value space assets in time of crisis and/or conflict? How could such a treaty be sufficiently verified? How would it be enforced? How would dual- use technologies be treated? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author(s): Dr. John Stevenson (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

The expert contributors divided nearly evenly on whether international space agreements can provide protection to space assets. While all contributors agreed that international agreements create norms of behavior, they disagreed on whether these norms create restraints on state behavior that will hold in a crisis. The contributors who did believe that international agreements could provide protection also maintained that focusing on prohibited activities, such as the generation of space debris, rather than prohibited technologies, increased the enforceability and verification of effective international space agreements as well as mitigated the dual-use problem. In short, their argument was that with regard to dual-use technology, ultimately it does not matter what states build, it really only matters how they use what they put into space.

Do Non-Institutionalized International Agreements Provide Asset Protection in Crisis?

The expert contributors were nearly evenly split on whether international agreements can effectively protect high-value space assets in time of crisis or conflict. Twelve experts affirmed the effectiveness of these agreements, whereas the eleven other experts dissented from this view.

Agreements can protect high-value assets

The expert contributors with more sanguine views of the effectiveness of international agreements in protecting space assets grounded their optimism in what they defended as the efficacy of existing space law. For example, Dr. Nancy Gallagher of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland describes the existing Outer Space Treaty (OST) as an effective agreement that is likely the best possible international agreement that could arise in the space domain. She avers that “it would be hard to get international agreement on any set of principles that would be better than what is currently laid out.” Buttressing Dr. Gallagher’s view that the OST’s centering common principles makes the agreement quite effective despite low institutionalization, Massimo Pellegrino, a Space and Security Policy Advisor in Geneva, maintains that widely-shared principles increase the enforceability of international space agreements, which helps to prevent and shape crisis behavior. Pellegrino states that, while states can disregard international law, doing so imposes sufficient costs, and these costs are factored into their strategies of compliance and non-compliance: There is enough of a “price to pay” for non-compliance that when “high enough [may] force nation states to restrain themselves” from attacking high-valued assets.

To the extent that international space agreements create and sustain these conditions of restraint by imposing costs, they would be effective in protecting high-value space assets in crisis or conflict. These collectively imposed costs can occur both domestically and internationally, even in the absence of institutionalization. On the domestic front, as Dr. Frans von der Dunk of the University of Nebraska College of Law observes, “it becomes very tricky for governments to be seen as violating [widely-shared] rules because it undercuts their own legitimacy.” With respect to international mechanisms of restraint, Dr. Xavier Pasco of the Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique Paris argues that collective space dependence creates a restraining self-enforcing interdependence functionally regulating state behavior. Pasco suspects that each country possessing space systems likely wants its “own space system to work properly,” creating a condition of “constrained interdependency” concerning “collective behaviors and rules as references for military actions.”

Agreements cannot protect high-value assets

In contrast, the remaining experts were clear that based on their interpretations of norms during historical crises, they believed agreements to be insufficient. For example, Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin categorically posits that “neither norms nor formal treaty obligations can be expected to protect high- value space assets in the event of crisis or conflict,” indicating that international space agreements, irrespective of the degree of formalization and institutionalization, provide few protections in crises. Similarly, Dr. George Nield of the Federal Aviation Administration shared that “it’s clear to me that international agreements cannot guarantee the protection of space assets,” but did not appear to embrace Berkowitz’s more expansive claim about norms.

For some of the experts in the ‘yes’ camp, the ability to impose costs was sufficient to conclude that international space agreements are effective in protecting high-value assets. In contrast, the ‘no’ camp adopts a stricter level of scrutiny, wanting something closer to 100% effectiveness to be able to reasonably conclude in favor of the proposition. The experts that viewed international agreements as ineffective in protecting high-value assets seem united in suggesting crisis-resilient protection is likely beyond the capacity of any agreement to obtain. Christopher Johnson of the Secure World Foundation observed that the inability of agreements to provide security in crisis “is not a defect of international agreements, merely a reality of the international political system.” Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland provides a contrasting view, arguing that it is intellectually unfair to require that international space agreements are 100% effective to be considered useful. She challenges proponents of views that unequivocally dismiss international space agreements to identify “a weapon system that is 100% effective” because there are “no doubt legal agreements (i.e., a ban on use of debris creating weapons; or “protection zones” regarding close approach of satellites on orbit) that could actively protect assets in crisis/conflicts and be verified, but need to be explored more thoroughly.”

Unlike many in the ‘no’ camp, Dr. Mark J. Sundahl of Cleveland-Marshall College of Law grounded his pessimism about the effectiveness of international agreements in space in the design of the Outer Space Treaty. He laments that, as currently designed, the OST permits a wide range of state behaviors, including actions that some states may consider aggression. Moreover, the treaty forbids only non-consultation with other governments in the event of potential interference with national activity in space. He states that:

I don’t think anyone believes that all weapons are banned from space…[what is banned is] nuclear weapons, [and] you can’t be aggressive, and you have to avoid harmful interference with the activities of other countries and their nationals. That is a rather soft prohibition on interference because all it really requires is that if you are going to harmfully interfere with the operations of others, then the governments have to consult with each other. It doesn’t say that interference is outright prohibited.

For Sundahl, the OST’s focus on principles, rather than institutionalization and monitoring, creates a weakness in the treaty. He believes that the OST cannot protect high-value space assets in time of crisis or conflict because the remedies for violation are mere consultation, rather than any form of imposed punishment or monitoring.

Enforcement and Verification Concerns as International Space Agreements Evolve

The contributors offered that enforcement issues surrounding international space agreements might be thought of as a specialized subset of those that arise in international arms control agreements. Effective arms control regimes exist in other areas of law plagued by dual-use issues, such as “universal prohibitions on biological and chemical weapons,” notes Michael Spies of the United Nations Office of the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs. Therefore, he believes the general mantra of arms control agreements was also true for international space agreements: Verification is enforcement.

A “good set of rules” creates guaranteed penalties “in the case of non-observance,” Dr. Luca Rossettini of D-Orbit avers. Well-designed international space agreements “can provide one layer of protection,” according to Nield, via “peer pressure, in terms of expectations of behavior that are held by the international community.” These behavioral expectations, Johnson observes, “establish what is internationally permissible to do.” This provides security benefits to states insofar as the “resources to be spent protecting against” impermissible activities “can be lessened.”

Drawing inspiration from international arms control agreements, the experts suggested three ways that international space agreements could be enforced and verified in the context of dual-use challenges. First, as space agreements evolve, continue to center them on widely-held norms. According to Dr. Moriba Jah of the University of Texas at Austin, these norms should be “things that promote transparency and are things that are measurable, and not measurable just by one entity but measurable by the community at large.” In the context of arms control agreements, codes of norms function in this way because epistemic communities can achieve verification by “corroborat[ing] or refut[ing] any given event” and then “quantify[ing]…the harmfulness of that event” to determine how to enforce the treaty violation.

Second, as an agreement evolves, participants should seek to regulate activities, not technology. Pellegrino plainly forwards that, “it would be beneficial if international agreements would focus more on the degree of care with which space activities and operations are conducted and communicated, rather than on which kind of orbital system/spacecraft is actually deployed in outer space.” Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson of the United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College agrees: “Since all space technology is dual-use, and every satellite can be a weapon…you cannot regulate technology, only specify what might be an illegal action.” Hitchens posits that an “Incidents at Sea/Dangerous Military Practices type agreement for space” is an excellent model for international space agreements.

Finally, even if agreements do not allow for institutionalization, detailing mechanisms and practices of transparency can overcome dual-use concerns. Pasco states that the question of dual-use technologies is “additional motivation for extended transparency mechanisms.” Pasco’s views dovetail with Spies’ thoughts on the function of transparency in mitigating dual-use concerns: “transparency and confidence- building measures can contribute to the development of verification measures for arms control agreements and regimes.” These mechanisms should cover three state practices in particular: “major outer space research and space applications programs, major military outer space expenditure, and other national security space activities.”

Conclusion

There was a bifurcation among the expert contributors on whether international space agreements can provide protection of critical space assets in a crisis, with half of the experts arguing ‘yes,’ and the other half arguing ‘no.’ The most effective international agreements, according to the experts, would require continued flexibility as well as clear verification to be enforceable and designed for the long haul. As such, agreements that focus on prohibited activities, such as the generation of space debris, rather than prohibited technologies, both increase the enforceability and verification of effective international space agreements, as well as mitigate the dual-use feature that almost all space technologies evince. To enforce is to verify: Ultimately, from the point of an effective agreement, it does not matter what states build, it really only matters how they use what they put into space and how easily other states can confirm that what a state says it is doing is what it is in fact doing.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Faulconer Consulting Group; Dr. Nancy Gallagher (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson (United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Dr. Peter L. Hays (George Washington University); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Christopher Johnson (Secure World Foundation); Tanja Masson-Zwaan (Leiden University, Netherlands); Dr. George Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Michiru Nishida (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Japan); Dr. Xavier Pasco (Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, France); Massimo Pellegrino (Space and Security Policy Advisor, Geneva); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Matthew Schaefer and Jack M. Beard (University of Nebraska College of Law); Dr. Michael K. Simpson (Secure World Foundation); Michael Spies (United Nations Office of the High Representative for Disarmament Affairs); Dr. Cassandra Steer (Women in International Security-Canada, Canada); Dr. Mark J. Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska College of Law); Joanne Wheeler (Bird & Bird, UK)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q1] Are there any contentious space terms or definitions, or are there any noticeable disagreements amongst space communities about appropriate terminologies and/or appropriate definitions for terms? What are the common understandings and uses of space-related terms, definitions, classes and typologies of infrastructure and access? For example, how do we define different classes of space users (e.g., true space-faring states, users of space technology)? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Sabrina Polansky (Pagano) (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

Operationalizing or defining terms is an important first step to understanding concepts, including their boundaries and how they are distinguished from other, potentially related ideas. Similarly, clarity in communication is an essential condition for ensuring that the message or information that is transmitted is as close as possible to what is received. Within the DOD, definitions matter because they are a necessary component for the establishment and application of doctrine. Given the breadth of the space field as a whole, establishing precise definitions may become an even more pressing task, as coordination is sought over a broad base of space sub-communities (e.g., national security space, civil space, and commercial). Each field as a whole and each sub-domain within it naturally has its own terminology, which tends to evolve over time. To best advance coordination within and across the various US and allied space communities, we must be capable of fruitfully combining the work that is being done in various commands, DOD offices, and other agencies and organizations. This can be best achieved when we identify those terms for which precise definitions are required in order to move forward. Doing so also enables the US to avoid any unintended responses from our adversaries. This coordination begins by getting a broad view of the terminological landscape and any terms for which there is current contention.

Drawing on a wide variety of space expert opinions, we identified three different ways in which terms could be contentious. These include: 1) explicitly acknowledged contention, disagreement, or variation in terminology (inherent contention), 2) contention that was not explicitly acknowledged by respondents but discovered through comparison across contributors’ definitions and commentary (emergent contention), and 3) ambiguous terms, which make contention more likely (potential contention). We refer to these different forms of contention collectively as “contentious space terminology.” This assessment is accompanied by an examination of how membership in a given community of space professionals— government, commercial, and analysts4—relates to the kinds of space terms thought to be in contention.

These terminological issues are not necessarily only epistemological in nature, but instead can have important implications for the space field. While not every term in contention will have an obvious or detrimental effect on the ability of the US to operate in or maintain security in space, other terms in contention—such as “space weapons”—may prove problematic for long-term US security interests. As Michael Sherry of the National Air and Space Intelligence Center notes, “Due to the confusion in terminology and misalignment with DOD regular terminology, we have found it difficult in the space community to build systems clearly aligned to a mission.” As such, this report provides a deeper exploration of a set of space terms whose contention may present major security concerns for the US.

Do experts perceive that there is contention in space terminology?

The original question posed began with the assumption that there are common space terms used by different communities of space professionals. To address this, we began by first examining whether there is commonality or variation overall in the terminology that is used, and whether variation occurs as a function of our experts’ professional affiliations.

The majority of subject matter experts (67% overall) indicated directly or indirectly that there is space terminology that is either inherently or potentially contentious. Those working in an analytic capacity (69%)6 or in the commercial domain (69%) more frequently indicated that there is contentious terminology than did subject matter experts working in government. As Colonel David Miller of the US Air Force indicated, “We have tried to come around to using DOD Joint Doctrine as the basis for our terminology, and I think within the Defense Department, we’re pretty good there.” Despite this organizing doctrine, 56% of government respondents (who tended to focus on security) nonetheless indicated that there is contentious space terminology.

Among the current contributors, the most frequent issue contributing to terminology being contentious is its inconsistent use—both across the national security and commercial sectors and within each of these sectors. The variation in use of space terms within the USG is not really surprising given that, as Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor7 of Orbital ATK indicates, the US emphasizes the separation of space into civil (e.g., NASA, NOAA, and USGS) and national security space (e.g., NRO, DARPA, Services) sectors—sub- communities that we might expect would utilize terminology in different ways. On the other hand, Dr. John Karpiscak III of the Army Geospatial Center suggests that differences in the application of a given term could be due to the differences between military branches that primarily ‘own’ versus those who most actively use assets in space (such as the Air Force and the Army). Those working outside of government also observed some variation in the use of terms within the DOD. Referencing Joint Publications and the US Space Policy, Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin noted that,

- the most authoritative DOD documents defining the US national security space lexicon (DODD 3100.10, Space Policy, JP 1-02, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, and JP 3-14, Space Operations) frequently have been inconsistent over the past few decades. Even the definitions of the basic defense space missions have changed frequently.

Ultimately, we cannot assume that everyone—even within a given sub-community working on space—is using the same set of definitions or has the same perspective on space issues given the segmentation inherent to the organization of the US space enterprise, as well as the variation in expertise, topical focus, and concerns of the diverse US space communities.8 This is problematic because it can impede the application of military doctrine, as implied by Sherry’s comments. Moreover, it can potentially hinder collaboration between the US and its prospective allied or commercial partners, leading to inefficiencies.

Contributors in fact offered several specific examples of terms that are contentious. These inputs address both inherent and potential forms of definitional contention, as described above. Additionally, several terms demonstrated emergent contention when variation was observed across the breadth of space expert contributors. To provide an overview of findings, all contentious terms are captured in the table at the end of this summary response. As can be seen from the table, contentious space terms related to security are most numerous, though contention also arises in other instances, such as legal/regulatory. Not all of these terms are necessarily problematic, however. This report thus will focus on examining two terms whose contention has particularly significant implications for national security.

When do contentious terms become problematic?

In many cases, contentious terminology may not matter—or ambiguity may even be desirable

A small minority of experts indicated that variations in terminology simply may not matter. In general, these contributors argued that any discrepancies that might occur could be easily overcome with communication. In addition, some operations may not require precise definitions of terms and/or individuals can resolve or work around them if necessary. Terminological ambiguity might even be desirable as it preserves options, and has, as several current contributors note, been useful to the US in the past when it comes to space issues. Moreover, David Koplow of Georgetown University suggests that attempting to achieve terminological consistency across national lines, public and private lines, and among different space sectors may be misguided; instead, he argues, the focus should be on clearly indicating how terms are being used when they come up, with the understanding that others may use or interpret these terms differently. Though this is likely to be true in many cases—and in particular when working within the US space community or operating alongside allies with whom we would expect this type of coordination—in other cases, it may not be sufficient to wait until an event (e.g., an ASAT test) invokes a potentially related concept (e.g., space weapons) over which different parties may have varying viewpoints.

In other cases, the stakes are high: space weapons and armed attacks

Broadly speaking, contentious terms become problematic when they have the potential to negatively affect the US and its security and other interests. At the more benign end of this spectrum, contentious terminology can lead to inefficiencies and impede collaboration, as noted above. However, at the other end of the spectrum, the stakes are higher, as contentious terminology can lead to misperception of US capabilities or actions among our adversaries, with unintended downstream consequences including escalation and retaliation. There is also the possibility that the US itself will miss or misinterpret its adversaries’ intentions.

To illustrate how this might be so, this report focuses on two examples9 of terminology identified as being contentious—one of which can be broadly categorized as a capability or object (space weapons) and the other which can be categorized as an action (armed attack).

In her discussion of space weapons, Victoria Samson of the Secure World Foundation provides an example of when definitional contention can become important: “…when you talk about security issues, of course the concept of what is a space weapon comes up all the time. The way it could be defined, it could be defined so generally that everything is a space weapon or so strictly that nothing is a space weapon.” This matters because, in the absence of a clearly specified and commonly agreed upon definition, different states may perceive the same capability or object in very different ways based on the way that they are defining a space weapon.

This subjective interpretation contributes to a cognitive bias known as naïve realism—the belief that our perception of the world is the true or correct perception of the world,11 and that others must necessarily see things in the same way (Jones & Nisbett, 1987; Robinson, Keltner, Ward, & Ross, 1995; Ross & Ward, 1996).12 Where one state sees a benign use of a capability, another can see a looming threat—and infer that the other side must therefore intend that threat. The wide application of dual-use space technology13 makes inferring intent from capabilities alone particularly difficult. Unlike the US space sector, in most other states, the private and public space sectors have more permeable—or no—boundaries at all, and neither are there separate civil and military government space sectors.14 Both the organization of space operations and the nature of the technology itself thus increase the possibility that a given state’s intentions can easily be misconstrued. This in turn increases the potential for escalatory or retaliatory behavior when no threat was intended.

This potential for unintended escalation may not yet be fully anticipated in the case of space weapons or weaponization of space, as most experts did not recognize that space weapon (or relatedly, weaponization) was a contentious term. Rather, it was identified as contentious primarily due to the variation in definitions offered by the subject matter experts. Jonty Kasku-Jackson of the National Security Space Institute draws on work by Vasani (2017), noting that the weaponization of space “includes placing weapons in outer space or on heavenly bodies as well as creating weapons that travel from Earth to attack targets in space… [in other words], outer space itself emerges as the battleground.” Brian Weeden of the Secure World Foundation emphasizes the key aspect of space weapons as being intentionally designed to damage, degrade, or destroy another object in space or something on the ground. The type of variation that can be observed here was also indicated directly or indirectly by several contributors (Pollpeter, Samson, Spies, B. Weeden). For example, Michael Spies of the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs indicates that the term space weapon is contested internationally. He discusses the definition of space weapon offered in Article 1 (b) of the draft treaty on the prevention of placement of weapons in outer space,15 noting that the definition does not address terrestrially-based anti-satellite systems (which would, incidentally, be covered under the prior two definitions above). Though there is some cross-over in the definitions offered by the respondents, there is also enough variation among these definitions to suggest that there is not overall coordination among the US space community on this important topic. This is not to say that any one definition is right or wrong—simply that the definitions vary and that this variation has implications. For example, an overall lack of coordination within the US space community on what constitutes a space weapon decreases both the likelihood of coordination with allies and of averting unintended consequences with adversaries.

Similarly, the definition of a space weapon is also likely yoked to the definition of what constitutes an “armed attack,” or relatedly, “[harmful] interference” or the “use of force” in space. As Jack Beard of the University of Nebraska College of Law queries, “Is making a satellite wobble out of its projected orbit an illegal ‘use of force?’ Is it ‘interference’?”16 Having different concepts of where the boundaries of each of these terms lies once again opens up the potential for conflict, and as Beard notes, “what constitutes an armed attack justifying an armed response is a really controversial topic.” At the same time, as Moriba Jah of the University of Texas at Austin indicates, actors such as Russia are strongly in favor of defining terms such as harmful interference, given its interest in invoking “self-defense” in space. As such, the US must balance the need for precision in terminology with the previously indicated utility of ambiguity in serving US interests.

How space weapons and armed attacks are defined also dovetails with another contentious term—outer space. Maintaining ambiguity in the definition and delimination of outer space has generally been strategically useful to the US (B. Weeden). However, defining outer space may matter for security in terms of designating lines of authority, planning, and response. As Patrick Stadter of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory notes,

- if you start to have adversary deploying access that transcend different domains, is it a missile? Does it go into space? At that point, those things become very very important relative to integrated strategic plans and OPLANs and command authority and how that’s reflected in policy. That will matter. It already matters a lot, and it’s a challenge.

Variations in the use of terminology and potential misperception are likely to increase with the widening gap in assumptions, norms, or ideologies that might be observed when different countries come to the table. For example, Dean Cheng of the Heritage Foundation and Asian Studies Center at the Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, provides some initial insight into how other states may view the issue of space weapons, indicating that the Chinese ultimately think about space and military impact on

space as anything that affects the entire holistic space structure.17 The breadth of this classification of course leaves the door wide open for the perception that the use of a given capability may constitute use of a space weapon, and thus require a response. Thus could begin an escalatory cycle that could be avoided if a common agreement instead is reached regarding what does and does not constitute use of a space weapon or weaponization of space. As it is, Kasku-Jackson notes, there are already some concerns that the US will fold under its definition of “peaceful purposes” (National Space Policy, 2010) both the militarization and the weaponization of space for national and homeland security activities. This fear may make others more likely still to misperceive the use of certain kinds of US capabilities in space as being intended as a space weapon—and thus execute their perceived proportional response.

Conclusion

The true power of definitions lies in their ability to facilitate communication within and across groups and states operating in space and, ultimately, in their ability to facilitate the achievement of US goals, including the maintenace of stability in space. As Brigadier General Thomas Gould (USAF ret.) of the Harris Corporation indicates, the US should aim to provide leadership in the definition of norms (and presumably, associated space terms). This view was echoed by Samson, who notes that norms and international cooperation may be the best route by which to achieve stability and predictability in space, with reliable access to space assets. In the case of space weapons, a failure to establish common definitions and associated norms can result in misperceptions that can leave the US and other space actors in a precarious position. Samson cautions, however, that by talking about space weaponization, the conversation is led down a road that may not be necessary or helpful. Instead, she argues, it may be more helpful to talk about stability, which is “a broader concept that contextualizes the domain and allows you to talk about anything that destabilizes the space domain.” Thus, by having a broader understanding of the array of things for which space is actually used, she argues, we might more readily disambiguate some of these points of confusion or contention.

Contributors

Roberto Aceti (OHB Italia, S.p.A. a Subsidiary of OHB, Italy); Adranos Energetics; Brett Alexander (Blue Origin); Anonymous Commercial Executives; Anonymous US Launch Executive; Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Brett Biddington (Biddington Research Pty Ltd, Australia); Bryce Space and Technology; Caelus Partners, LLC; Elliott Carol3 (Ripple Aerospace, Norway); Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Matthew Chwastek (Orbital Insight); Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (ret.) Deron Jackson (USAFA); Faulconer Consulting Group; Jonathan Fox (Defense Threat Reduction Agency); Joanne Gabrynowicz (University of Mississippi School of Law); Dr. Nancy Gallagher (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Harris Corporation; Dr. Jason Held (Saber Astronautics, Australia); Dr. Henry Hertzfeld (George Washington University); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Jonathan Hung (Singapore Space and Technology Association, Singapore); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Dr. John Karpiscak III (US Army Geospatial Center); Jonty Kasku-Jackson (National Security Space Institute); Dr. T.S. Kelso (Analytical Graphics Inc.); David Koplow (Georgetown Law); Group Captain (Indian Air Force, ret.) Ajey Lele (Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, Centre on Strategic Technologies, India); Dr. Martin Lindsey (US Pacific Command); Agnieszka Lukaszczyk (Planet, Netherlands); Elsbeth Magilton (University of Nebraska College of Law); Colonel David Miller (United States Air Force); Dr. George C. Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Kevin Pollpeter (CNA); Victoria Samson (Secure World Foundation); Matthew Schaefer and Jack Beard (University of Nebraska College of Law); Michael Sherry (National Air and Space Intelligence Center); Brent Sherwood (NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory); Michael Spies (UN Office for Disarmament Affairs); Dr. Patrick A. Stadter (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory); Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; Dr. Mark Sundahl (Cleveland-Marshall College of Law); John Thornton (Astrobotic Technology); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Frans von der Dunk (University of Nebraska); Deborah Westphal (Toffler Associates); Dr. Brian Weeden (Secure World Foundation); Charity Weeden (Satellite Industry Association, Canada); Joanne Wheeler (Bird and Bird, UK)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

The Meaning of ISIS Defeat and Shaping Stability — Highlights from CENTCOM Round 1, 2 and 3 Reach-back Reports.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Conclusion

ISIS will be defeated militarily. However, whether it is ultimately overcome by containment or by deploying ground forces to apply overwhelming force, the path to mitigating violent extremism in the region is a generations-long one. Military options are insufficient to protect US interests and stabilize the region. It will require significant strengthening of State Department and non-DOD capacity to help build inclusive political institutions and processes that protect minority rights in Syria and Iraq. Only if these flourish will ISIS — the organization and the idea it represents — have failed and the region been put on a sustainable path to stability.

Since September 2016 the Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) team has pulsed its global network of academics, think tank scholars, former ambassadors, and experienced practitioners to respond to three rounds of questions by USCENTCOM.3 We received responses from 164 experts from institutions in the US, Iraq, Spain, Israel, the UK, Lebanon, Canada, France and Qatar. 4 The result was 41 individual reach- back reports, each of which consists of an executive summary and the input received from the experts.

This report summarizes key points from the first three rounds of questions. It compiles what the experts had to say about three critical questions: 1) Will military defeat of ISIS in Syria and Iraq eliminate the threat it poses? 2) What are the implications of ISIS defeat for regional stability? and 3) What should the US/Coalition do to help stabilize the region?

[Q9] What are the biggest hindrances to a successful relationship between the private and government space sectors? How can these be minimized? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

The 33 individuals or teams that provided input represent large, medium, and small/start-up space companies; 4 USG civil space agencies; academia; think tanks; and professional organizations. Four of these are non-US voices (Australia, Canada, Italy, and Norway.)

The consensus view among the expert contributors to this report is that a successful and sustained government- commercial relationship in the space domain is as essential for achieving US national security goals as it is for achieving commercial profits.5 At present, however, contributors see the ways in which US civil and National Security Space (NSS) operate as barring the attributes that make for an attractive business environment, including: a) clear requirements and data exchange between government and commercial partners, b) persistent and predictable funding and cash flow, c) non onerous and consistently implemented export controls, and d) synchronization of internal government agendas and decision making with regard to space.

The following sections discuss four themes related to US public and private space sector relations (i.e., US civil and National Security Space and the commercial sector) that emerge in the input provided by the expert contributors. While one of the themes focuses on positive aspects of the relationship, the other three themes focus on types of barriers—namely, red tape, culture, and organization of the bureaucracy. The frequency of mentions for each of these themes, as well as for specific examples of each given by the contributors, is summarized in the Figure below. These themes are discussed in greater detail below. It should be noted that, unless specified, there was no association between an expert’s views and his or her professional affiliation. The barriers and mitigation options discussed here were identified as much by NSS and US civil space voices as by commercial and scholarly ones.

First, the Good News…

Although the question of focus prompted experts to address hindrances, nearly a third (30%) of the contributors feel that relations between US public and private space sectors are fairly good. In fact, even among contributors who see significant barriers, several identify specific organizations and programs as exemplars of ways to make USG space a more attractive and accessible business environment.6 NASA is the governmental organization that is most frequently cited as having made progress in cutting red tape and developing innovative ways to work with commercial actors. The FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation is the second most cited, followed by NOAA and then finally, some programs at NGA.7

The Barriers

The majority (70%) of expert contributors mentioned at least one of three types of important barriers that hinder relations between the commercial sector and US National Security Space. “Red Tape” refers to barriers imposed by USG regulatory and acquisition/contracting processes. “Culture” captures barriers that contributors suggest arise from the different goals, expectations, and cultures of the NSS and commercial space communities. Finally, “Organization of Bureaucracy” addresses impediments that result from the organization and structure of the US bureaucracy.

#1: Red Tape

What are described as opaque, convoluted, and slow US regulatory and acquisition/contracting processes are the hindrances that are most frequently mentioned by contributors.

The Barriers

In a sentiment echoed by other contributors, Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor of Orbital ATK suggests that problems with space acquisition do not just reside within bureaucratic machines, but often emerge at the outset from “a poor requirements process—[the NSS] can’t decide what it wants.” Dr. George C. Nield of the Federal Aviation Administration offers a reason for why this is so: “the nature of the DOD organizational structure, namely lots of people can say ‘no,’ but no one’s empowered to say ‘yes’.”

What is the impact on the commercial sector? In short, the effect is increased costs of doing business with NSS. When acquisition and contracting processes are difficult to navigate, involve so many steps, and require extended periods to reach contract award, the transaction costs of working with the USG can become higher than the value of the work itself—a negative business case that is extremely difficult to defend to shareholders and investors. Lengthy periods of uncertainty involved in securing work with NSS also increase financial risk to companies who must spend up-front capital to pursue NSS work.8 Smaller companies may experience additional barriers. Three contributions from small or start-up businesses find that current acquisition processes may benefit “entrenched interests” and make it difficult for smaller firms to compete with larger, better-known prime contractors.9 Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland sees the issue as reciprocal—that is, the “creakiness/complexity of the acquisition process at DOD and NASA” also makes it harder for the USG to find and work with smaller companies.

While contributors were sympathetic to the necessity of government oversight of dual-use technologies with national security implications, many believe that this oversight is overly restrictive, unfair to US firms, and/or prone to what Joshua Hampson of the Niskanen Center tags as the “capriciousness and opaqueness” of decisions about export controls.10 More than half of the expert responses mention inconsistently implemented, “burdensome” and/or “outdated” mandatory Federal Acquisition egulation (FAR) requirements, International Traffics in Arms Regulation (ITAR), and other compliance requirements as major barriers to successful relations between public and private sector space. There are two inevitable results of restrictive export controls. First, activities such as moving space- related items from general export controls to ITAR put US companies at a disadvantage relative to foreign competitors, and create a situation that eventually will incentivize companies to leave the US for areas with more lenient controls.12 Second, as Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy) argues, a restrictive environment invites competition from foreign governments eager to attract business away from the US.

#2: Cultural Differences

What experts saw as “cultural” barriers to government-commercial partnerships in the space domain were attitudes and behaviors rooted in the different agendas, priorities, motives, incentive structures, and varying speeds of operations of government and commercial space. Contributors described two specific sources of culture clashes: differences in expectations about the operational environment, and different concepts of information sharing and control.