SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Question (R3 QL7): How does Da’esh’s transition to insurgency manifest itself in Syria; which other jihadist groups might offer the potential for merger and which areas of ungoverned space are most likely to offer conditions conducive for Da’esh to maintain some form of organizational structure and military effectiveness?

Author | Editor: Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc).

Da’esh Transition in Syria

The contributors varied in their discussions of what a Da’esh transition—or the future of Syria more broadly—would look like. Drawing on work by Gelvin, Pagano suggests that three scenarios are most likely for Da’esh’s transition in Syria. These include the complete destruction and disappearance of the group and its ideology; transition into an insurgent group capable of conducting limited operations in Syria and/or inspiring attacks abroad; or disintegration into a loose collection of former fighters and free agents conducting attacks, in some cases without organizational support. Finally, University of Oklahoma ME expert, Dr. Joshua Landis, indicated that while it is difficult to generalize, the extreme factionalization that characterized Syria prior to Da’esh’s involvement would likely come back into play. As such, we may expect a revived emphasis on the clan or tribe, with ongoing resistance to central government. Landis continued by suggesting that sufficient weakening of Da’esh will eventually enable the Syrian government led by Assad to regain broad control.

The contributors to this Quick Look indicated that we may observe the following for Da’esh in Syria and abroad:

Ongoing actions in Syria

- continued agitation and exploitation of the uncertainty and dysfunction in Syria

- ongoing efforts to be present and to expand

Change in strategy and associated tactics

- reorientation toward increasing attacks abroad

- shift from acquisition and maintenance of territory to insurgent methods aimed at weakening enemies

- increased emphasis on both terrorist and insurgent tactics (e.g., recent attacks in Paris and Brussels)

- movement away from direct attacks toward scorched earth defensive strategy combined with aggressive insurgency tactics

- return to indiscriminate urban violence, using lone wolves and small militant groups

- increased use of two-tiered attacks (first soft civilian targets, then first responders)

- use of “mobile, dispersed, and flexible units” that operate on behalf of Da’esh Da’esh Alliances

Views among the contributors on the groups with whom Da’esh might align demonstrated some degree of consensus. Both Shaikh and Pagano indicated that a merger or strong alliance between Da’esh and other groups would be highly unlikely. This was due in part to Da’esh’s history of denouncing others as apostates when they failed to conform to its strict rules and interpretations of Islam. Da’esh’s rigid approach has resulted in eventual isolation and the creation of enemies among groups with which it might under different circumstances have allied. Shaikh also emphasized the breadth of the ideological divide between Da’esh and other groups, which would in turn make it difficult for Da’esh to justify any future cooperation with so-called deviant groups. While Pagano cites possible points of Da’esh ideological convergence with either Jabhat Fateh al Sham or the quietest Salafists, the likelihood of collaboration between these groups remains very low. These points of convergence would be dependent on a shift in Da’esh’s goals and subsequent motives as it is faced with the fall of the caliphate, which might make previously unlikely alliances necessary for the sake of survival and future goal pursuit.

Use of “Ungoverned Spaces”

Liebl put forth the view that ‘ungoverned space’ does not truly exist given that formal or informal political institutions will always exist where there are people. Shaikh however focused on likely future contests for “ungoverned” spaces in Syria, suggesting that that the primary competition would be between Da’esh and Al Qaeda given their rivalry and different organizational purpose and approaches. Landis briefly addressed the topic by suggesting that the proportion of ungoverned space in Syria will decrease as Da’esh is weakened, and the Syrian regime retakes the west and parts of eastern Syria. Pagano emphasizes areas of strategic or symbolic importance to Da’esh and the existing or potential loss of these resources. She reviews the status of northern Aleppo province, Raqqa, and Deir el-Zour, as well as the recent retaking of Palmyra, and concludes by briefly listing the conditions under which these spaces would provide the greatest utility or opportunity to Da’esh.

Contributing Authors

Dr. Joshua Landis (University of Oklahoma); Vern Liebl (Center for Advanced Operational Culture, USMC); Dr. Sabrina Pagano (NSI, Inc.); Mubin Shaikh (University of Liverpool)

Geopolitical Visions In Chinese Media.

Author | Editor: Hinck, R., Manly, J., Kluver, R. & Norris, W. (Texas A&M University).

Executive Summary

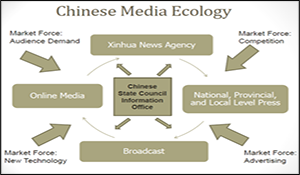

This study analyzed Chinese web media in an effort to uncover key frames and cultural scripts that are likely to shape potential geopolitical relationships in Asia. The team provided an overview of Chinese media and developed individual reports on cultural scripts in media coverage of three key issues: a) China’s relationships with its regional neighbors, b) the geopolitical dimensions of the “China Dream” (中国梦), and c) Chinese discourse around the “New Style Great Power Relations” (新型大国关系). Data was collected from May to October 2014. Over 2,200 media articles were analyzed from 25 different Chinese media sources controlled for ownership, political slant, official versus, and popular media outlets.

While understanding today’s news agenda will not predict China’s policy over a two decade timeline, the news agenda and media coverage can help uncover deeper components of Chinese political culture, including the world views, assumptions, and geopolitical expectations of China’s leaders. Daily media coverage enacts cultural scripts, and in the case of Chinese media in particular, reflect carefully crafted policy positions agreed upon by Chinese elites behind closed doors. While specific policies can change quite quickly, the underlying societal scripts and political culture are more enduring. Thus, media analysis can help unveil grand narratives of Chinese political visions and capture the underlying national mood which provides constraints to future behavior.

Key Findings

- Chinese foreign policy discourse portrays China as primarily responding to international provocation. While China seeks a stable international environment, it is portrayed as needing to respond to provocative actions committed by others.

- Far from being a threat to the existing geopolitical order, China’s economic and military rise provides opportunities for all nations to benefit.

- The US and its regional allies are portrayed as perpetuating a false China Threat thesis aimed at containing China. The US is seen as the primary enabler of aggressive policies committed by Japan and the Philippines.

- The Chinese media relies heavily on historical allusions to paint Japan as a militant country.

- The US is overwhelmingly the most important and frequently discussed country regarding China’s international relations.

- The China Dream constitutes a domestic and international vision describing China’s peaceful rise promising mutual benefit to all those willing to share in China’s rise.

- The China Dream promises economic prosperity, a return to military strength, emphasizes China’s cultural prestige, and legitimizes the Chinese Communist Parties role in reestablishing China’s greatness following its century of humiliation beginning with the Opium Wars in the 1840s.

- The New Style of Great Power Relations is China’s attempt to avoid the pathologies of historical Great Power conflict with the United States. The concept lays out significant areas for US-China economic and military cooperation, but challenges US policy in the Asia Pacific as failing to live up to the tacitly agreed upon principles of mutual respect and positive relations between the two nations.

Implications & Recommendations

- There is political room for collaboration. In the event that the United States seeks common ground from which to build more cooperative relations with China, this study found evidence suggesting that domestic Chinese media portrayals of some of the most prominent “guiding concepts” that have been articulated by Xi Jinping could provide opportunities that can be leveraged to foster a more cooperative tone in the military-diplomatic relationship.

- US agencies should leverage an understanding of Chinese frames to position US activities for maximum impact by identifying the dominant frames and themes in Chinese media. US engagement with China tends to focus on a different set of frames (such as “responsible stakeholder” or “human rights”) that are at variance with Chinese frames, and thus, US concerns rarely enter Chinese consciousness or are seen as intrinsically oppositional to Chinese priorities. By more explicitly framing US policies within the frames and norms of Chinese media, it might be possible to articulate US concerns to a broader Chinese audience.

- Do not allow counter-productive narratives to go uncontested. US policies are often portrayed in Chinese media in a negative light (i.e., US actions undermine new style great power relations), and this portrayal is rarely countered in US discourse. By understanding how these frames are articulated, it is possible to advance US policies within a framework of collaborative, rather than competitive, ties.

- Proceed with caution and address differences frankly. Although there are areas that might be ripe for greater cooperation, the US would be well- advised to proceed cautiously and be aware of potential rhetorical traps. Specifically, we recommend that any engagement for cooperative purposes that seeks to leverage some of these dominant themes and concepts be proactively defined by the US. Areas of difference in interpretation or emphasis or specific meanings that China might have regarding some of these ambiguous and vague concepts should be directly and forthrightly addressed even as the US might seek to build a more cooperative footing based on some of these ideas.

- Any effort to proceed along a cooperative vector with China is likely going to need broader support beyond just a single US government agency. If the US is looking to actively seek out areas for regional cooperation, we find that there is sufficient material in the Chinese media discourse that can be used to bolster that effort. However, a successful cooperative engagement approach would necessitate a larger US interagency approach to China.

Question (R5.2): What are the risks associated with the security situation in Syria/Iraq outpacing

diplomatic progress and policy in the region? What should be done about it?

Author | Editor: S. Canna (NSI, Inc,).

Executive Summary

Our experts noted that we cannot say with certainty what the future security environment will look like in the Middle East. The region “is highly fluid. And fluidity means that alliances are temporary and that it’s very difficult to draw any long-term or even medium-term perspectives on what might happen,” Dr. Ehteshami noted. Limited visibility into the future is compounded by the sheer number of inflection points facing actors in the region as each tries to shape the environment in its favor.

The concern that security developments could outpace diplomatic efforts is well founded. The table below identifies the inflection points—or catalysts—discussed by contributors where security developments could outpace the ability of local and regional actors to respond.

According to Daniel Serwer, one of the few remaining options for the US in Syria is to work to ensure that Assad and Iran do not dominate post-war Syria. This is because, as Faysal Itani notes, the United States has accepted that the “regime and its partners have essentially won the war” in Syria.

As Hala Abdullah notes, “everything seems to be happening in Iraq at once.” In fact, most of the issues and risks identified in the table above focus on Iraq. According to Vern Liebl, potential catalysts in Iraq range from the re-emergence of ISIS as an insurgency to a sudden positive shift of Sunni attitudes towards the Iraqi government. Many of the catalysts listed are interrelated in a highly complex system, which is why the potential responses to these problems are strikingly similar; they all require US diplomatic and policy actions. It is worth noting that the catalyst most frequently cited by contributors is the lack of US leadership and clearly stated goals in the region (Abdulla, Bahgat, Ehteshami, GCKN, Serwer).

Contributors

Hala Abdulla, Center for Advanced Operational Cultural Learning (CAOCL), USMC University; Gawdat Bahgat, National Defense University; Anoush Ehteshami, Durham University (UK); Global Cultural Knowledge Network Staff, US ARMY TRADOC G2; Zana Gulmohamad, University of Sheffield (UK); Sabina Henneberg, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies; Faysal Itani, Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East; Vern Liebl, Center for Advanced Operational Cultural Learning (CAOCL), USMC University; Daniel Serwer, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies

Author | Editor: W. Aviles & S. Canna (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

A strong argument can be made that we are moving toward a pluralized, multipolar world, in which military and economic sources of power are widely distributed. Technologies (e.g., the Internet and rapid means of mass migration) are making nation states increasingly more porous, and a resurgence of nationalism and other forms of ethnic or religious identity politics has solidified some states and weakened others. Given these properties of human development, the question remains as to how nations and societies position themselves to ride these revolutionary changes with some degree of confidence. The continuance of these factors may change the way that the US, its partners, and its adversaries consider and prioritize influence, both within the state and across interstate borders. The DOD is evolving in ways that demand a more synergistic approach than we have traditionally taken across the human and technical dimensions. To date, military operations have characteristically focused on compelling adversaries through the threat or application of force to achieve victory (i.e. “control”). Changing environmental factors, increased activism by non-state actors, technology, and recent lessons learned suggest that the DOD will be challenged to adopt revised, if not entirely new approaches, to affect and direct the outcomes of military operations. Toward such ends, the DOD will need to focus upon the factors and forces that exert the necessary influence to produce desired behavioral outcomes across complex and intermeshed human and technical systems.

This white paper examines these trends and explores and presents possible implications for how such factors may necessitate an explicit focus upon “influence” rather than “control,” and how influence could exert effects on national, regional, and global levels over the next several decades. It assesses these revolutionary changes from political, sociological, biological, and technical perspectives.

In her opening chapter, Ms. Regina Joseph (NYU) examines the coming tests of preserving national security through influence. She reviews the domestic information environment, where corporate interests generate a confluence of content and access barriers, and observes the global influence efforts that will continue to buffet society. While difficult, resilience may be cultivated through an offset that harnesses Western attitudes towards information, education, and cultivation of super-synthesizers. She goes on to say that to envision the future, a forecaster may first look to the past in an effort to find signals and detect patterns.

In the following chapter entitled “From Concepts to Capabilities: Implications for the OPS Community,” Lt General (Ret) Robert J. Elder (George Mason University) examines the implications of the changes in our security environment, considers the ways that different international actors are capitalizing on these changes, and reflects on their implications for the United States and our partners. He notes that today’s national and military leaders have grown up in an environment where the strategic military objective has been to defeat the adversary, but in today’s environment, restoring or preserving stability has often become the primary strategic objective. Competitors understand the U.S. desire to win, and leverage that against us by employing a “don’t lose” strategy. They consider a draw to be a win because they have prevented the U.S. from winning, and like Tic-Tac-Toe, they just wait for the U.S. to make a mistake. This suggests that employing whole of government and partner capabilities to advance overall U.S. national interests, even if it does not lead to a military “win,” may be a preferable strategy, and one that national security leaders should promote. Draws are not in our nature–winning is the American Way– but if a competitor is playing for a military draw, then defeating the competitor’s strategy by employing a comprehensive approach to promote stability may be in our national interest.

In the following article entitled “Net Assessment: Implications for Homeland Security,” Dr. Gina Ligon (University of Nebraska Omaha), Ms. Gia Harrigan (Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, Office of University Programs), Dr. Erik Dahl (Naval Postgraduate School), Mr. Timothy N. Moughon (National Counterterrorism Center), Colonel Bill Edwards (Special Operations Northern Command), and Nawar Shora (Transportation Security Administration) examine implications from a homeland security perspective. They address the issue of how net assessment—the practice of considering how strategic interactions between the United States, adversaries, and the environment may play out in the future—may be adopted to advance homeland security (especially as related to threats that emerge outside the homeland). In this chapter with contributors from government and academia, implications of using a net assessment approach to understand influence is discussed. They detail the overarching framework for net assessments. They then review the approach from NCTC on measuring power and the criticality of assessing “Green Actors.” They conclude by highlighting some of the challenges faced by Blue Network, as well as how net assessments can provide greater shared understanding of emerging threats to homeland security by incorporating planning for threats, capabilities, and legitimacy.

Next in a chapter entitled “From Failure to Success: Information Power and Paradigmatic Shifts in Strategy and Operational Art,” LTC Scott Thomson (Office of the Secretary of Defense (Policy), Information Operations Directorate) takes the argument to the next step and examines the underlying assumptions about war, warfare, and other military operations within the DOD, which traditionally focuses on lethal dominance. He makes the argument that strategy is inherently about changing the behavior of relevant actors in support of national interests. This means information must be a primary planning consideration for the joint force rather than an enabling capability. To better link tactics to strategy, the joint force must change both its operational art and its cultural mindset to focus on behavioral outcomes. He concludes by stating that to shift our dominant paradigm will take a concerted effort and direction by senior leaders within the department. The department must realize that while it looks to improve informational capabilities, it is more important to first modify the operating system of the joint force so that it can realize the full power of information to achieve strategy.

Next in their chapter entitled “Rethinking Control and Influence in the Age of Complex Geopolitical Systems,” Dr. Val Sitterle (GTRI), COL (ret) Chuck Eassa (Strategic Capability Office), Dr. Robert Toguchi (USASOC), and Dr. Nick Wright (Univ. of Birmingham) in line with LTC Scott Thompson’s chapter make the case that the future of conflict facing the DOD is evolving in ways that demand a more synergistic approach than we have traditionally taken across the human and technical dimensions. To date, military operations have characteristically focused on compelling adversaries through the threat or application of force to achieve victory (i.e., “control”). Changing environmental factors, increased activism by nonstate actors, technology, and recent lessons learned suggest that the DOD will be challenged to adopt revised, if not entirely new approaches to affect and direct the outcomes of military operations. Toward such ends, the DOD will need to focus upon the factors and forces that exert the necessary influence to produce desired behavioral outcomes across complex and intermeshed human and technical systems.

In the following chapter entitled “Metaphor for a New Age: Emergence, Co-evolution, Complexity, or Something Else?” Dr. Val Sitterle (GTRI), Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI), Dr. Corey Lofdahl (System of Systems Analytics), and CAPT (ret) Todd Veazie locate these challenges in the context of complex adaptive systems paradigm. They ask, as globalization and sociotechnical convergence collide with the continuing evolution of the post-Cold War security environment, do we know the appropriate metaphors to describe our world? Our environment is now characterized by non-uniformity and starts, stops, and leaps across orders of magnitude and across geographical areas and socio-economic- political sectors. They ask how the lenses through which we view and draw conclusions about various aspects of the world and the behaviors within it change and what can we perceive and, hence, act upon? Understanding the nature of paradigms and how we use them to provide insight in the US Defense community is critical to how well we may face future security challenges.

In his chapter entitled “Don’t Shortchange Defense Efforts to Inform, Influence, and Persuade,” Dr. Christopher Paul (RAND) argues that capabilities to inform, influence, and persuade are necessary both for national security success and as a cost-effective toolset relative to physical military power. He discusses shortfalls and deficiencies in this area and concludes with recommendations to increase resources for manning and tools for informing, influencing, and persuading, as well as efforts to inculcate communication mindedness in commanders and senior leaders.

In his chapter entitled “Operationalizing the Social Battlefield,” Dr. Spencer Meredith III (National Defense University) argues the diffusion of influence from traditional elites to broader and more diverse sources has raised challenges for the United States, but not inherent risks by itself. The tools used to mobilize individuals and groups within society have for some time existed across a spectrum of industries, academic disciplines, and ultimately, government actions. As such, while the ubiquity of influence has ratcheted up in recent years, it has not fundamentally altered who can be influenced or the means of doing so. Evaluating how these phenomena affect the Joint Force Commander’s range of options and, more importantly, strategic paradigms on ways, means, and ends, must include several elements. These include governance, mobilization potential, and narrative landscapes.

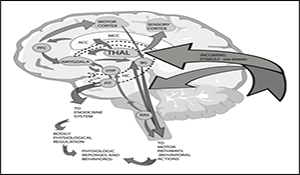

In the subsequent several chapters, the reader is exposed to the neuro-cognitive aspects of control and influence. In the first two Chapters, Dr. Nick Wright (University of Birmingham) encourages the reader to rethink control and influence. He states at the outset that influence and control are two ways to exert power over others’ decisions, where control removes an audience’s ability to choose. Influence is critical in conflicts such as those in the Gray Zone, whose limited nature leaves adversaries and allies able to choose. He concludes by stating many aspects of influence and control do not need rethinking. He goes on to encourage the reader to focus on three key aspects of influence: (1) using more realistic accounts of human motivation, (2) focusing on areas of particular human cognitive bias as a source of low- hanging fruit for performance improvement, and finally (3) using tried and tested tools and techniques from other fields (e.g., medicine) to make evidence available in usable forms for operators.

In the following chapter entitled “Evidence Based Principles of Influence,” Dr. Wright stresses the need for scientific approaches (i.e., what do we know, and how can we know it?). He advances three key considerations: First, the reader should be aware of the replication crisis in the scientific literature in this area. Second, in order to accumulate robust scientific knowledge about the factors that influence people, the reader needs to focus on empirical findings. Finally, there is a level-of-analysis problem. To consider influence and persuasion, you have to think about multiple levels simultaneously.

In the following chapter, Dr. James Giordano (Georgetown) in an article titled “Neuroscience and Technology as Weapons on the Twenty-First Century World Stage” makes the case that neuroscience and neurotechnologies (neuroS/T) can be used as (1) “soft” weapons to foster power, which can be leveraged through exertion of effects upon global markets to impact nation states and people as well as to provide information and tools to more capably affect human psychology in engagements of and between agents and actors; and (2) “hard” (e.g., chemical, biological, and/or technological) weapons: including pharmacological and microbiological agents, organic toxins, devices that alter functions of the nervous system to affect thought, emotion and behaviors, and use of small scale neurotechnologies to remotely control movements of insects and small mammals to create “cyborg drones” for surveillance or infiltration operations. He goes on to say that brain sciences can also be employed to mitigate or prevent aggression, violence, and warfare by supplementing HUMINT, SIGINT, and COMINT (in an approach termed “neuro-cognitive intel”: NEURINT). Such possible applications generate two core questions: (1) to what extent can these technologies be developed and used to exert power? And, (2) how should research and use of the neurosciences be best engaged, guided, and governed? He goes on to address following issues: (1) the current capabilities of neuroS/T for operational use in intelligence, military, and warfighting operations; (2) potential benefits, burdens, and risks incurred; (3) key ethical issues and questions, and (4) possible paths toward resolution of these questions to enable technically right and ethically sound use toward maintaining international security.

Dr. Christophe Morin (Fielding Graduate University) in his chapter argues it is crucial that we recognize the urgency of using better persuasion models to create and evaluate both propaganda and counter- propaganda campaigns. Also, the dynamic and implicit nature of the effect of media content on adolescent minds highlights the necessity of conducting experiments that reveal the neurophysiological effect of messages on young brains. Subjects cannot competently and objectively report how messages work on their minds. However, new research tools used by neuromarkers can reveal critical insights by safely and ethically monitoring different subsystems in the nervous systems while participants view persuasive messages.

Drs. David A. Broniatowski (The George Washington University) and Valerie F. Reyna Cornell University) in their article entitled “A Scientific Approach to Combating Misinformation and Disinformation Online,” argue for a scientific approach to combating online misinformation and disinformation. Such an approach must be grounded in empirically validated theory, and is necessarily interdisciplinary, requiring insights from decision science, computer science, the social sciences, and systems integration. Relevant research has been conducted on the psychology of online narratives, providing a foundation for understanding why some messages are compelling and spread through social media networks, but this research must be integrated with research from other disciplines.

In his article entilted “Neural Influence and Behavior Change,” Dr. Ian McCulloh (Johns Hopkins University), argues that military commanders and senior leaders must have a basic understanding of cognitive influence in order to make decisions affecting the Gray Zone and human populations in areas of ongoing military operations. Influence is counter-intuitive. This has led to poor decisions that may have adversely affected the success of US operations. He provides a primer of cognitive influence, set in tactical military terms. The intent is to inform commanders and senior leaders to enable them to make better decisions regarding inform-influence operations in support of US objectives. Success during Gray Zone operations requires commanders to understand influence and employ models of behavior change in the same manner that they understand the elements of patrolling and employ kinetic power.

In his article entitled “The Role of Integrative Complexity in Forecasting and Influence,” Dr. Peter Suedfeld and Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (The University of British Columbia) argue that If control is dependent on actual or at least perceived power—political, economic, military, demographic, and other—influence is the product of an even more varied and changing set of variables. The criteria that define the probability of success in exerting or countering influence must include two factors: accuracy in assessing the possible steps of an adversary and shaping persuasive communications so as to advance one’s own position and reduce the power of the opponent’s. The former aspect, anticipatory intelligence, has been a major research focus to date. They briefly look at what may be a fruitful approach to the latter. In short, besides being a tool for anticipatory intelligence analysis, Integrative Complexity may also be used to help shape persuasive communications as well as responses to adversarial attempts at persuasion.

In his article entilted “Neural Influence and Behavior Change,” Dr. Ian McCulloh (Johns Hopkins University) argues that military commanders and senior leaders must have a basic understanding of cognitive influence in order to make decisions affecting the Gray Zone and human populations in areas of ongoing military operations. Influence is counter-intuitive. This has led to poor decisions that may have adversely affected the success of US operations. He provides a primer of cognitive influence, set in tactical military terms. The intent is to inform commanders and senior leaders to enable them to make better decisions regarding inform-influence operations in support of US objectives. Success during Gray Zone operations requires commanders to understand influence and employ models of behavior change in the same manner that they understand the elements of patrolling and employ kinetic power.

In his article entitled “The Role of Integrative Complexity in Forecasting and Influence,” Dr. Peter Suedfeld and Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (The University of British Columbia) argue that If control is dependent on actual or at least perceived power—political, economic, military, demographic, and other—influence is the product of an even more varied and changing set of variables. The criteria that define the probability of success in exerting or countering influence must include two factors: accuracy in assessing the possible steps of an adversary and shaping persuasive communications so as to advance one’s own position and reduce the power of the opponent’s. The former aspect, anticipatory intelligence, has been a major research focus to date. They briefly look at what may be a fruitful approach to the latter. In short, besides being a tool for anticipatory intelligence analysis, Integrative Complexity may also be used to help shape persuasive communications as well as responses to adversarial attempts at persuasion.

Author | Editor: Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The Physical Defeat of ISIS video addresses if a physical defeat of ISIS fully eliminate the threat it poses? Highlighting some of the work NSI has conducted as part of a Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) team Reach Back Cell in support of USCENTCOM, this video discusses the future of ISIS.

A Primer on the Neurocognitive Science of Aggression, Decision Making, and Deterrence.

Author | Editor: DiEuliis, D. (Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction, National Defense University) & Giordano, J. (Departments of Neurology and Biochemistry, Georgetown University Medical Center).

Executive Summary

here are numerous national security challenges relative and relevant to the aggressive and/or violent intent and behavior of individuals, groups, and societies. In an ever more networked world, the ways that people think, emote, and behave are being increasingly affected by social, and informational factors; many made possible or fortified by the iterative use of various forms of technology. Despite demonstrably positive outcomes of such trends, there are also clear and present burdens, risks, threats and harms in the geo-political sphere that current and near-future social and technical developments can, and likely will incur.

A recent global risks study by an international forum of experts elucidated such geo-political and societal threats to national security, and emphasized interactive elements including social instability, individual and groups’ vulnerability to social volatility, radicalization, terrorism, and interstate conflict, as being strongly contributory1. Each and all of these factors can be conceptually and practically reduced to the decisions and actions made by individuals, and/or groups, whether acting alone or as state actors. Attempts to investigate contributory variables and possible causes of such threats to social stability and peace have entailed a variety of disciplines (e.g. – social and political sciences, anthropology, psychology, economics, etc.). Thus, resulting theories of correlation and causality reflect the diversity of these disciplines’ approach(es) and focus, to include resource scarcity, perceived unfairness, pride/nationalism, vengeance, anticipation of reprisal, preservation of cultural norms, and risk/threat and fear of harm, and/or death. Such studies have paved the way for various agencies within the United States government (USG) to consider the use of a variety of tools to address these issues in national security, intelligence and defense (NSID) operations to prevent violence, deter unwanted actors, and foster cooperation.

1. How have regional governments responded to Ma’soud Barzani’s announcement of a referendum on Iraqi Kurdish independence to be held in September? 2. How have different sub-state groups responded, to include different Kurdish factions in Iraq and across borders? 3. How are the Kurds using the independence referendum to leverage their interests?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

Why now?

President Ma’soud Barzani has been promising a referendum on Kurdish independence since 2014, so we have to ask the question why now? The non-binding referendum, if approved, will not necessarily mean a declaration of independence (Atran, Rasheed, Wahab). Barzani has admitted that the purpose of the referendum was not to declare independence but to gauge the opinions and rights of the Kurds in Iraq (Anonymous 2). But there are several factors potentially driving Barzani’s decision to announce a referendum now.

- Strengthen a long-term bid for greater autonomy (Atran, van den Toorn)

- Create a better negotiating position in any settlement that follows the liberation of ISIS-controlled territory including oil-rich regions (Anonymous 1, Anonymous 2, Atran, Hamasaeed, van den Toorn, Wahab)

- Push to permit foreign/military aid to go directly to Erbil rather than through Baghdad (Atran)

- Consolidate Barzani credibility as well as his political, military and economic hold over Erbil and large portions of the KRG (Anonymous 2, Atran). Barzani’s credibility will be particularly important to either secure his legacy as he steps down from the presidency at the end of his term this year or to provide a justification for a third unconstitutional term (van den Toorn)

- Shore up domestic support for Barzani’s administration, which is facing a “legitimacy crisis” due to 1) the inability of the KRG to pay salaries on time or in full, 2) that Parliament has not met in nearly two years, and 3) that Barzani is in his second “unconstitutional” term (these all contribute to the “crisis of legitimacy,” not just salaries, though that is a big one (Anonymous 1, Anonymous 2, Hamasaeed, van den Toorn)

- To authenticate Barzani’s nationalist credentials particularly at a time when the PKK is gaining influence across the Kurdish territories transnationally and inside the Kurdistan Region (Anonymous 2)

- In rejecting all of the above reasons, Amjed Rasheed—a Kurdish specialist at Durham University— stated (in a minority opinion) that Kurdish leadership “genuinely believes that it is a time of the Kurds to achieve their inspiration and dream to become an independent state.”

Expected Outcome for Kurds

The Movement for Change (Gorran) along with the Kurdistan Islamic Group (key oppositional Kurdish political parties) declined to participate in the committee organizing the referendum (Anonymous 1, Atran, Gulmohamad, Wahab). An expert who prefers to remain anonymous concluded, “What you see is that for perhaps the first time in Iraqi Kurdish modern history, the independence project – and thus, Kurdish nationalism itself – has been politicized” internally among Iraqi Kurds. Christine van den Toorn, director of the Institute for Regional and International Studies at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani, expects that the referendum will increase divisions within Kurdish political parties as well as between political elites and the people—essentially along the lines of those in favor vs. those against the referendum.

A second anonymous contributor argues that it has already led to targeted threats against those Kurds, mainly independent and opposition groups, who oppose the referendum without a functioning parliament in place. This group, mobilized under the No to a Referendum movement, includes over 100 journalists and writers thus far. Also, the deputy head of the KDP faction in the defunct Iraqi Kurdistan parliament announced on the KDP information website that a campaign against the referendum “will be punished by the court of people and history will never be merciful.” Erbil police also just official closed the Standard Institute office, which is a civil society organization, for “criticizing Peshmerga and the referendum.” Other journalists have received death threats for opposing the referendum.

Hamasaeed suggests that the referendum was essentially part of a long-term Kurdish shaping operation preparing the groundwork for a future Kurdish state. Kurds are particularly motivated to act now, while they still have leverage given their role in fighting ISIS, to push for independence in the event that Nouri Al- Maliki and a pro-Shia/anti-Kurdish government comes to power in the upcoming elections (Wahab). Therefore, success from a Kurdish perspective is a referendum that does not result in a firm public or international “no” (Hamasaeed).

However, the second anonymous contributor disagrees with the assertion that the Kurdish are motivated to act now. She notes that the referendum “is a tactic to divert domestic and international attention away from the Kurdistan Region’s deep-seated internal problems. It is part of the post-ISIS preparations being made among many groups to leverage Baghdad. Even within the KDP officials know that ‘now is not the time’ and that the region needs to build up its institutions first. This can be perceived as a desperate measure by Barzani as he faces challenges to his authority, namely by the PKK, which has gained influence in his region, and a rising Baghdad.”

Regional Responses

There is no official international support for the referendum at this time. Reactions range from mild opposition (not against greater Kurdish independence, but think the timing is not right) to strongly worded opposition. Kurdish leaders were reportedly not surprised by foreign governments’ negative reaction to the announced referendum (Gulmohamad, Rasheed, Wahab). The United Nations has also stated that it will have no role and does not support the referendum. Given this, the second anonymous contributor questioned who would be the independent actors to monitor the referendum vote?

Countries with Kurdish populations strongly opposed to Kurdish independence

As might be expected, countries with Kurdish populations—Turkey, Syria, and Iran—strongly oppose any movement towards Kurdish independence in Iraq (Anonymous 1, Atran). These countries include Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq (Atran).

Turkey called the referendum a “grave mistake” (Anonymous 1, Anonymous 2, Atran, Gulmohamad, Hamasaeed, Wahab, Waziri). Scott Atran, a researcher who conducts field research in Iraqi Kurdistan, suggested that a concerted push for independence could trigger increased Turkish military action not only against the PKK in Iraq, including near the Iranian border, but also more sustain cross-border incursions and de facto holding of Kurdish Iraqi and Syrian (YPG) territory. However, Sarhang Hamasaeed, USIP’s Director of Middle East Programs, questioned whether there is a difference between the public statements of countries, like Turkey, and what they privately discuss with Kurdish leadership. Some speculate that the Kurds would not make an announcement like this if there were not tacit approval or expectation of tacit approval from Turkey (Hamasaeed, Rasheed, van den Toorn, Waziri).

Iran is strongly opposed to Kurdish independence in Iraq (Anonymous 2, Rasheed, Wahab, Waziri), but some say it has not been as vocal as Turkey because the government does not believe this referendum will actually lead towards independence (Anonymous 1, Anonymous 2, van den Toorn). In fact, the referendum—if interpreted as a sign of increasing internal Kurdish divisions—could increase Iranian influence over Kurdish parties in eastern Kurdistan (Anonymous 1). But Atran argues that the Iranians are taking the threat of Kurdish independence seriously with Qassim Soleimani, head of Iran’s Quds Force, demanding that the Kurdish flag be removed from Kirkuk. Hoshang Waziri states that an independent Kurdistan is a red line for Iran—that it will never accept a smaller, Shia-led Iraq.

The Iraqi government also opposes the ability of any one group deciding “the fate of Iraq, in isolation from other parties,” according to Iraqi government spokesman Saad al-Haddithi (Gulmohamad, Rasheed, Wahab). Abadi recognized the Kurds’ political aspirations for greater autonomy, but suggested the time is not ripe for these discussions. Hamasaeed reminded readers that Iraq is in an election season and political leaders stated opposition might be driven by efforts to look strong and patriotic. Moreover, other provinces, such as Basrah, oppose the Kurdish referendum and notions of independence because they would not permit the KRG to take resources and territories that they believe are an integral part of the Iraqi state. A key issue is the disputed territories and whether they will be included in this referendum.

Most other governments think the time is not right

Most other governments with interests in the region—UK, US, EU, Germany, and Russia—are either not supportive or not encouraging at this particularly point in time (Anonymous 1, Gulmohamad, Rasheed, van den Toorn, Wahab). They fear independence would be a distraction in the fight against ISIS (Anonymous 1, Gulmohamad). The US is concerned that a successful push for autonomy would weaken the Abadi government and embolden his pro-Iran rivals, which would undercut long-term US security relations with Iraq (Wahab). The US State Department and US Government does not support the referendum (Anonymous 2).

Regional Kurdish groups support the referendum

Despite evidence of divisions among Kurdish political parties for the referendum, regional Kurdish groups that have fought with the Peshmerga—including the PKK (Turkey), YPG (Syria), and the PAK (Iran) support the referendum (Atran, Rasheed). There are conditions of PUK support (which is fractured), which is that the Kurdish parliament is first reactivated and that all of the disputed territories are included (Anonymous 2).

Shia groups in Iraq strongly oppose the referendum

Shia groups, including the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), strongly oppose the referendum. Additionally, the State of Law bloc—a Shia-led coalition in parliament—rejected the referendum, which would lead to the division of the country.

Iraqi Sunni group have mixed response

Some Sunni tribes and militia would accept Kurdish independence if they, too, could have autonomy in Sunni areas (Atran). However, Sajida al-Afandi, an influential parliamentarian of the Sunni Union of National Forces stated, “Neither the domestic nor the foreign circumstances are currently ripe for Kurdistan’s secession from Iraq.” Sunni groups are particularly opposed to Kurdish territorial ambitions in disputed areas such as Kirkuk. However, some Sunni Arabs in disputed territories prefer the Kurds to the Shia militias for now (Rasheed, van den Toorn), but this support “is ephemeral and transient” until ISIS is defeated and Sunnis Arab have a new opening to renegotiate their position with the government in Baghdad. Kurds seek to capitalize on this. Other Sunni Arab groups reject Kurdish overreach and have joined Hashd or are waiting for the return of ISF, federal government forces and authority (van den Toorn). The Sunni Arabs have also been less vocal because many are living inside the Kurdistan Region at this moment and are dependent on Masud – at least for the time being (Anonymous 2).

Non-Kurdish minorities want to be left alone

Non-Kurdish minorities in disputed territories, particularly Ninewa, want their autonomy and to be left alone (van den Toorn). While KRG officials claim they have support from minorities, populations near Ninewah most likely would prefer a united province under a united Iraq. The referendum is likely to expose and exacerbate tensions between minority groups and the KRG. Minority groups are also divided (Anonymous 2). Some do support the KDP and Barzani while others lean toward Baghdad. These loyalties are also transactional and can change over time, depending upon who can provide services, security, and jobs.

What does this mean for the US?

A second expert, who prefers to remain anonymous due to frequent travel to the region, stresses that it is essential that the USG does not overreact to this move. She argues that the US has significant leverage over the Kurds and should not give in to the threats Barzani makes. It should not officially endorse or support the referendum, or any other unilateral measure taken by the KRG that seeks to bypass official state institutions. Much of this is for public consumption in the West, as well as to his local constituencies. She warns that “[b]y overly coddling and enabling Barzani, the US will dissuade any necessary negotiation that needs to take place between Baghdad and Erbil, as well as institution building that is sorely needed in the Kurdistan Region. The US should avoid stirring the ire and tensions among local groups seeking their own form of self protection and autonomy, let along the Iraqi government, by supporting the KRG’s extension of territories through a unilateral move (referendum). This is particularly important given the outcomes of the anti-ISIS campaign and the extensive territories that the Kurds have expanded their de-facto control. The U.S, should continue to emphasize its commitment to the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the Iraqi state. It should enhance Iraqi state institutions and continue to channel any support to Iraqi sub-state actors through the Iraqi government. Any future resolution to Iraq’s territories and borders should be negotiated between the KRG and Baghdad.”

According to this second anonymous expert, many Kurds state that the only people really making an issue of this are non-Kurds. “Barzani can back away from the threat of pushing for independence because he has done so already, and can even use the failure to do so as a conspiracy by outsiders against Kurds. He can play the victim card as save face. Also there is no significant challenge to Barzani at this time – not from Arabs or other Iraqi Kurdish groups. The only real threat is from the PKK.”

Contributing Authors

Anonymous 1, Anonymous 2, Scott Atran (ARTIS), Weston Aviles (NSI), Zana Gulmohamad (Sheffield University), Sarhang Hamasaeed (United States Institute of Peace), Amjed Rasheed (Durham University), Christine van den Toorn (American University of Iraq, Sulaimani), Bilal Wahab (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Hoshang Waziri (Independent)

US-DiGIA: Overview and Methodology of US Discoverable Government Information Assets Directory.

Author | Editor: Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

The United States Government possesses a vast store of information assets that can be leveraged to inform a variety of problem sets, and can be used by a wide range of governmental actors in the formation and execution of whole-of-government strategies. To enable this goal, however, these assets first must be made accessible in a single source that catalogues the information that is held.

What is US-DiGIA?

The US “Discoverable Government Information Assets” Directory (US-DiGIA for short) resource catalogues the discoverable information assets (practical information, data, analysis, and subject matter expertise) relevant to national security and foreign policy held by the USG in a simple, easy- to-use searchable directory.

The US-DiGIA Directory is focused on “discoverable” information assets—that is, those information assets that are both open source (unclassified) and made available and/or identified as information assets held by the organizations that the NSI team examined. By focusing on which information assets are “discoverable,” this mapping does not claim to represent the true distribution of information assets across the whole-of-government, but instead captures what can be observed and obtained through unclassified channels—and thus potentially accessed via an interagency process.

US-DiGIA compiles and categorizes the information assets of 236 offices across 221 combined US government departments, agencies, and corporations (referred to collectively as “USG organizations”). US-DiGIA catalogues 1,305 unique information topics culled from these combined sources, and accounts for 1,980 total information topics (as some offices work on overlapping issues).

To create the US-DiGIA Directory, the NSI team developed a methodological process (detailed below in the section entitled, “US-DiGIA Mapping Methodology Process”) for taking the unstructured data culled from USG organization websites examined and translating them into information assets. The NSI team created an extended record2 of data sources, including mission statements, links to documents and tools, related web pages, and contact information. On the foundation of this rich source of information, the NSI team in turn developed the US-DiGIA Directory.

Gray Zone Conflicts, Challenges, and Opportunities – Executive Summaries of Team Reports

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc.).

Table of Contents

- SPECIFYING & SYSTEMATIZING HOW WE THINK ABOUT THE GRAY ZON

- RISK AND AMBIGUITY IN THE GRAY ZONE

- GEOPOLITICAL VISIONS IN CHINESE MEDIA

- EXAMINATIONS OF SAUDI-IRANIAN GRAY ZONE COMPETITION IN MENA, AND OF POTENTIAL OUTCOMES OF THE FLOW OF FOREIGN FIGHTERS TO THE UNITED STATES

- DEMYSTIFYING GRAY ZONE CONFLICT: A TYPOLOGY OF CONFLICT DYADS AND INSTRUMENTS OF POWER IN COLOMBIA, 2002-PRESENT

- DEMYSTIFYING GRAY ZONE CONFLICT: A TYPOLOGY OF CONFLICT DYADS AND INSTRUMENTS OF POWER IN LIBYA, 2014-PRESENT

- THE CONFLICT IN THE DONBAS BETWEEN GRAY AND BLACK: THE IMPORTANCE OF PERSPECTIVE

- DISCOURSE INDICATORS OF GRAY ZONE ACTIVITY: SOUTH CHINA SEA CASE STUDY

- DISCOURSE INDICATORS OF GRAY ZONE ACTIVITY: RUSSIAN-ESTONIAN RELATIONS CASE STUDY

- DISCOURSE INDICATORS OF GRAY ZONE ACTIVITY: CRIMEAN ANNEXATION CASE STUDY

- VIOLENT NON-STATE ACTORS IN THE GRAY ZONE A VIRTUAL THINK TANK ANALYSIS (VITTA)

- THE CHARACTERIZATION AND CONDITIONS OF THE GRAY ZONE: A VIRTUAL THINK TANK ANALYSIS (VITTA)

- DEMYSTIFYING GRAY ZONE CONFLICT: A TYPOLOGY OF CONFLICT DYADS AND INSTRUMENTS OF POWER IN COLOMBIA, LIBYA AND UKRAINE

- US DISCOVERABLE GOVERNMENT INFORMATION ASSETS DIRECTORY

- US-DIGIA: OVERVIEW AND METHODOLOGY OF US DISCOVERABLE GOVERNMENT INFORMATION ASSETS DIRECTORY

- US-DIGIA: MAPPING THE USG DISCOVERABLE INFORMATION TERRAIN: SOURCES OF NATIONAL SECURITY AND FOREIGN POLICY INFORMATION WITH A FOCUS ON GRAY ZONE IDENTIFICATION AND RESPONSE ACTIVITIES

- US-DIGIA: MAPPING THE USG DISCOVERABLE INFORMATION TERRAIN: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- FROM CONTROL TO INFLUENCE: COGNITION IN THE GREY ZONE

- VIOLATING NORMAL: HOW INTERNATIONAL NORMS TRANSGRESSIONS MAGNIFY GRAY ZONE CHALLENGES

- GRAY ZONE DETERRENCE: WHAT IT IS AND HOW (NOT) TO DO IT

- QUANTIFYING GRAY ZONE CONFLICT: (DE-)ESCALATORY TRENDS IN GRAY ZONE CONFLICTS IN COLOMBIA, LIBYA AND UKRAINE

- MEDIA VISIONS OF THE GRAY ZONE: CONTRASTING GEOPOLITICAL NARRATIVES IN RUSSIAN AND CHINESE MEDIA

- INTEGRATION REPORT: GRAY ZONE CONFLICTS, CHALLENGES, AND OPPORTUNITIES

Question (R4.8): Are there impediments to cooperation amongst GCC nations that reduce their effectiveness towards undesirable or adverse regional issues? If so, how could impediments be overcome?

Author | Editor: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

At the time of the writing of this executive summary, the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) has experienced a diplomatic crisis with three GCC member states (Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain) cutting diplomatic ties with Qatar (another GCC member state) and remaining GCC members (Kuwait and Oman) attempting to mediate. This event begs the discussion of factors and dynamics that obstruct or cripple cohesion among GCC nations and possible solutions to overcome such obstacles. A thorough understanding of the threats facing the GCC and more specifically, their limitations in responding to them, are crucial to attaining a vigorous and holistic comprehension of the Gulf region.

No SMA contributor contests that there are significant impediments to GCC cooperation. Furthermore, there are no significant disagreements among the authors; rather, each author emphasizes different points of contention and solution. Caban, Feierstein, Ulrichsen, and Sager all agree that the GCC is not a monolithic enterprise; instead, each nation is subject to varied and often competing interests (e.g., economic resources, international political capital, territory etc.). Serwer then further elaborates, “[GCC states] need to all hang together or they’ll all hang separately,” and all authors agree, or at least hint, that effective cooperation among GCC members would benefit each nation domestically and/or internationally. Disagreements and conflicts within the GCC go back decades, and Ulrichsen contends that the formation of the GCC as an institution was completed in such a poor and hasty manner that internal friction was inevitable from the start. The PiX Team provides an overview of the structure of the GCC and explains the purpose and functions of the GCC that span from a forum for joint infrastructure projects to a high level political assembly.

Iran, Foreign Policy, and Political Islam

Continuing the criticism of the design of the GCC, Ulrichsen points out that “the GCC has no explicit treaty- based foreign policy-making power as its founding charter called only for a coordination of foreign policy,” and the rest of the authors all agree that disagreements over foreign policy are a significant source of division within the GCC. Evidence of this division is exemplified by all authors agreeing that Iran is source of attenuation of unity among the GCC (e.g., through proxy conflicts in Iraq, Yemen, and Syria, as well as encroaching on territory in the Gulf). Feierstein and Sager posit that GCC members cannot come to a unified response to Iranian antagonism for a variety of reasons, ranging from various economic interest in Qatar, to Shia extremism in Bahrain and Kuwait. Feierstein provides a useful model of a spectrum with Saudi Arabia on the extreme anti-Iranian side and Oman on the more Iranian friendly side, with the remaining GCC states in between. This spectrum is evident in the current Qatari diplomatic crisis where Feierstein has contended prior to the rift that Iran is exploiting an opportunity in friendlier Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar to sow discord within the GCC and “isolate the Saudis.”

Iran manifests roadblocks to GCC cooperation through the sectarian conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and most prominently, Yemen; however, these flashpoints of conflict can also be viewed through the mechanism of radical/political Islam, through which Iran manipulates them. In this context, the variance among GCC nations in geographical location, socio-economic factors, religious populations and others, present the cracks in GCC cooperation that Iran is able to exacerbate—all to the detriment of the GCC’s ability to produce and implement a coherent and unified foreign policy. The role of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Yemen is a source of strife among GCC states where the Saudis and Emiratis both “opposed the rise of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood” in opposition to Qatar (Feierstein). And yet in Yemen, the UAE is far more opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood presence than Saudi Arabia (Ulrichsen). Political Islam is particularly concerning to GCC nations that must balance religious extremism with the legitimacy granted by religious institutions to the monarchies. Serwer and Caban recognize the divergence of domestic pressures of GCC nations that in turn deviate the interests of GCC nations from one another; different problems necessitate different solutions that make for weak and compromised policies on the international level.

Military Institutions and Security Structures

GCC nations face a diverse set of geopolitical and socio-economic challenges; foremost among them are concerns about security. Given the internal turmoil of sectarianism and external threat of Iran, coupled with the threat of terrorism that plagues GCC nations on all levels, the need for a cogent and reactive security force is paramount for Gulf regimes. Caban argues that GCC nations are “deficient of professional military forces [which] indicates an inability to perform joint operations; because [they] have limited and ad hoc professional military forces, they have insufficient capacity to work together effectively to thwart undesirable or adverse regional issues.” Caban goes on to describe that many GCC nations have a high ratio of migrant workers to “natural-born citizens vested in the sovereignty of the homeland,” which make recruitment difficult and outsourcing security forces necessary. Efforts by GCC nations to have their officers trained and educated outside the Gulf are being explored by the UAE, as well as hiring foreign military professionals, but there are adverse political and logistical consequences still unfolding as a result of these measures (Caban).

Feierstein agrees with Caban that an inability to perform joint operations is a monumental issue facing GCC nations, but instead emphasizes the root of the problem in the political structures of cooperation among member states. Feierstein notes that the disagreements of member states over the brevity of various threats can be explained through a political perspective. Feierstein argues, “GCC cooperation works best when the issues are apolitical and technocratic in nature, and can be framed in a way that benefits rather than challenges the power and authority of individual states,” and cites historical examples of such cooperation.

Solutions/Overcoming Challenges

Each author has proposed solutions to the challenges they each respectively highlighted in their contribution, again, with a high degree of concurrence. Sager asserts that a tenacious and unambiguous US policy in the region is critical to GCC success. Feierstein concurs with Sager’s point of the need for clear US policy in the region, but explicitly stresses Iranian issues as an area of focus. Feierstein also suggests that US must not try to force policy onto the GCC, but rather to cultivate it from within, so as to not feed the propaganda of Gulf regime submission to Western governments. Ulrichsen maintains that political and structural reform of the GCC would be helpful, and the GCC as an organization should focus on ameliorating “administrative mechanisms and less on big-ticket items that are perceived to impinge on sovereignty.” In regards to the problems facing GCC security forces that Caban describes in detail, “Developing a program for military officers at the war colleges and a series of annual military exercises would bring together GCC- only armed forces to promote greater familiarity and the development of common doctrine” (Feierstein).

Contributing Authors

William Cabán (Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University), Gerald Feierstein (Middle East Institute), PiX Team (Tesla Government Services), Abdulaziz Sager (Gulf Research Institute), Daniel Serwer (Middle East Institute), Kristian Coates Ulrichsen (Rice University)