SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

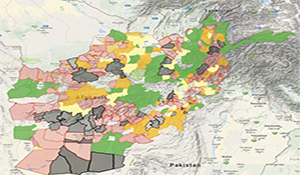

Question (R4.10): Is the current U.S. approach to supporting Afghanistan beneficial? Or does it promote a cycle of dependency and counter-productive activities in the region? What strategic and local factors would need to be considered, managed and accepted in any significant change in military and/or other support?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

Asked about any constructive aspects of the current US approach in Afghanistan the experts who contributed to this Reach-back report, to a one responded with lengthy, well-considered but scathing reviews of the past fifteen years of US/NATO policy and operations in Afghanistan. The majority of the experts — who include practitioners and political scientists, historians and hydrologists with years of on-the- ground experience with Afghanistan — felt there is nothing to commend current US policy toward Afghanistan. The others did not address the question.

In fact, most experts took the tack that the current US approach to Afghanistan (which they date to the “mission creep” that began in 2001) is itself the source of the insecurity, instability and Taliban resurgence happening now in Afghanistan.

The US Approach in Afghanistan

The central themes of the experts’ arguments can be summarized in two main points:

#1: State-building efforts detract from the real US interest in Afghanistan: security

Professor Shalini Venturelli (AU) argues that US activities in Afghanistan have drifted away from what is the true national interest in Afghanistan (security) to focusing on governance and state-building. Along with Spencer Meredith (NDU) she argues that the US must refine the focus of its approach to jettison objectives such as state-building and democratization that have distracted the US from issues that we have the relevant power to impact. Venturelli sees no value to US security from getting involved in the highly culturally- dependent issue of how a nation governs itself.

Instead: Venturelli argues in favor of a major reconceptualization of US policy in Afghanistan that focuses strongly on what is truly the core (and only reasonable) US mission there: US security. She suggests “three concrete components” of a reconceived US mission: 1) preventing and deterring terror group gains in Afghanistan by “expanding counter-terrorism operations in the AF-PAL region;” 2) preventing Afghanistan from becoming a major terror safe haven; and 3) building the capacity of the Afghan National Army (ANA) guided by a more sophisticated and culturally relevant training model that taps into the “indigenous fighting tradition” – (what Dr. Shireen Khan Burki refers to as Afghanistan’s “xenophobic warrior” population.) She cautions that continuing with the current approach of incrementally changing the US approach around the margins as circumstances dictate has already had “devastating consequences” and could be worse than withdrawing US military support altogether.

#2: There is insufficient socio-cultural foundation and local trust to support construction of centralized democracy in Afghanistan: These efforts were doomed to fail from the start

The experts who commented on the political or state-building aspects of the US approach did not mince words, referring to it as: “impractical and expensive,” the result of “overconfidence bordering on insanity” and “hopelessly corrupted and detrimental.” Spencer Meredith (NDU) believes that the US approach is based on the faulty assumption that localized/decentralized governance is at odds with a legitimate and capable national government. Others are highly critical of efforts to construct a Western-style centralized political system in Afghanistan with a very feeble foundation in Afghan political history, social organization or culture. It was doomed from the start. Shalini Venturelli (AU) reckons that “not all the wealth and expertise of the US and its NATO allies” would be sufficient to build a sustainable democratic state in Afghanistan because it would be out of line with the social, cultural and political traditions and expectations of the majority of the Afghan population.

Instead: The contributors who commented on this point agreed that rather than Western expectations of good governance and social and political stability, if the US chooses to remain involved in state-building in Afghanistan, its efforts must refocus on the expectations of the Afghan people. Venturelli points out that Afghan society already contains “highly evolved, complex and variable systems of social order that fall outside the capabilities of Western administrative science.” Specifically, Spencer Meredith (NDU) recommends that the US should patiently pursue a bottom-up, culturally and historically grounded approach to political development. Despite the fact he says that analysts in DC and certainly political elites in the central government in Kabul for obvious reasons do not like this option, it is the only one with a reasonable chance of producing a broadly accepted and legitimate government.

Does the US approach promote a cycle of dependency and counter-productive activities?

The majority opinion among the expert contributors to the Reach-back report is that the current US approach in Afghanistan does promote dependency and is counter-productive. Vern Liebl (CAOCL) among others questions why anyone would be surprised by the negative consequences of pouring billions of dollars of donor money into a devastatingly impoverished country. This aid has fueled elite corruption at the expense of the poorest Afghans which has in turn soured public opinion even more on the US-imposed central government and likely aided the resurgence of the popular acceptance of the Taliban. Benjamin Hopkins (GWU) sees the question of Afghan dependency itself is insulting to Afghans arguing that it is the West’s pursuit of “unrealistic policies” in Afghanistan not some Afghani flaw that has generated deleterious cycles. In addition to fueling government corruption for example, US policy has strapped the Kabul Government with unsustainable government institutions including a security force that “is well beyond the ability of the country to sustain. That said, “anti-corruption” measures are not the solution here. Shalini Venturelli cautions that Westerners/outsiders can easily misunderstand local norms of human networking and in correctly label some social-required activities as corruption. Rather than dismissing social influence networks outright, Venturelli recommends leveraging this existing system of relationships to advance security interests in Afghanistan.

What strategic factors should guide changes in US military or other support?

The authors are clear on this point: we cannot assess our strategic approach without a strategic vision. Reflecting the perspectives of her fellow contributors, Shireen Khan Burki asks the essential question: “What exactly is the strategic mission of the US vis-à-vis Afghanistan?” There is consensus among the experts who feel that the US approach has lacked a clear articulation of US goals and objectives in Afghanistan. Many are skeptical that there is a coherent strategic vision or set of mission objectives that would align with all the foreign activities and aid in Afghanistan. At the very least if they have been articulated, they have not been stated clearly in public. The experts pose a number of other questions that might serve as guides to review US policy in Afghanistan:

- “What are American goals in the country and how do they relate to US national interests?”

- “Who is the enemy?” There is a line of reasoning among the contributors that common responses to this question, for example, counter-terrorism, denying terror groups safe havens, ring hollow. First, there are many other places around the world including Pakistan that violent political networks can easily establish a presence, and secondly our own presence in Afghanistan has in fact exacerbated not minimized the ability of terror networks to recruit and operate in the country.

- “What if any interest [does] the US [have] in a stable vs. democratic Afghanistan?” In other words, what are US priorities regarding an acceptable political outcome if not all aspects can be achieved.

- Is it the mission of the US to fundamentally change Afghanistan?

Contributing Authors

Dr. Shireen Khan Burki (unaffiliated); Dr. Benjamin D. Hopkins (George Washington University); Dr. Shalini Venturelli (American University); Mr. Vern Liebl (Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, CAOCL); Dr. Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, SAIS); Dr. Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (Visual Teaching Technologies, LLC); Dr. Alex Dehgan (Conservation X Labs), Dr. Spencer Meredith (National Defense University)

Question (R4.11): What are the implications for the U.S. and GCC countries if the Arab coalition does not succeed or achieve an acceptable outcome in Yemen?

Author | Editor: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

Conflict in Yemen is now reaching the third year of its current incarnation, and despite the foreign intervention of GCC nations and several failed ceasefire attempts, the Houthi movement (Ansarullah) has continued to succeed on the battlefield. Several SMA contributors (e.g., Anonymous, Ulrichsen, & Cragin) suggest that the GCC campaign is unlikely to produce a desirable and timely military victory in Yemen. Ulrichsen and Cragin argue that rising domestic socio-economic costs of the Arab coalition campaign are outpacing a realistic timeline of a satisfactory outcome; moreover, Ulrichsen asserts that the Houthis have sufficient Iranian support and that the coalition is unable to combat “a foe that has nearly 40 years’ experience of running proxy groups throughout the Middle East.” Only one author (Styszynski) contends that an impending coalition offensive on the strategic West Coast ports of Yemen will be successful and force Houthi forces to engage in a peaceful, diplomatic end to the conflict.

Nazer notes that while the parties to the conflict generally understand what measures are necessary to end the conflict, they lack the political will to make necessary and difficult compromises. Because Saudi Arabia views a Houthi victory as an existential threat to Saudi Arabia, major concessions are unacceptable to GCC actors. Experts expect this to remain the case for the foreseeable future (Nazer, Ulrichsen, Feierstein and Ibish). However, this raises the importance of exploring realities where the Arab coalition fails to achieve the pre-2014 status-quo of a marginally stable, GCC-friendly Yemeni regime and has to grapple with some form of Houthi victory in Yemen.

Even defining what the success of the Arab coalition in Yemen looks like is not immediately clear among contributors. In large part this is due to the lack of a unified goal or vision of success among the Arab coalition. Feierstein, Ulrichsen, and Ibish all agree that a significant amount of disagreement and discord exists among coalition partners (particularly between Saudi Arabia and the UAE) as how to engage and end the Yemeni conflict; furthermore, all three contributors agree that losing the conflict exposes and exacerbates divides among the GCC. Disputes over strategy like engaging the Muslim Brotherhood as allies (Ulrichsen and Ibish) and friction over levels of coalition contributions among member states highlight the cracks in GCC unity. Considering Cragin’s timeline of the Hadi government being unable to regain “full control within the next 3-5 years,” a weakening of GCC cohesion is one of several far-reaching repercussions that extend beyond the borders of Yemen. It is worth noting that among the various implications of the Arab coalition failing to achieve a strategic victory in Yemen, there is remarkably little disagreement among the authors; rather each contributor emphasizes or discusses different consequences.

End State Discussion

Research conducted by the PiX team foresees “no end in sight” for the Yemen conflict. However, three contributors (Anonymous, Ibish, and Styszynski) discuss the possibility of a resolution where Houthis and other factions negotiate a settlement of partition to end the conflict. Ibish contends that the Arab coalition is entertaining the notion of conceding a degree of autonomy to the Houthi rebels in the north, whereas Anonymous puts forth an end of three territories with a southern governate supported by GCC countries and neutral middle governates buffering Houthi control to the north. All three authors agree that this scenario will likely set the stage for future conflict. The historical background provided by Liebl provides the cyclical evidence for such phenomenon.

One other outcome discussed by the contributors (Ibish, Liebl and Nazer) is the transition of the Houthi movement to a Hezbollah-like organization. Nazer states that a Hezbollah-styled insurgency would be considered an unacceptable outcome for Saudi Arabia; but again, as the conflict deepens and the GCC weakens, these difficult outcomes may have to be entertained by Gulf States.

US, Iran, and GCC relationships

The most commonly discussed implications in this corpus are the adverse strain among the various relationships of actors involved in Yemen, both internal and external. Many contributors argue that the Houthi uprising and subsequent Saudi involvement has become a severe liability to the domestic legitimacy of the House of Saud (Ulrichsen, Feierstein, Ibish, and Nazer) and that continued conflict and/or defeat will significantly contribute to the unraveling of the Saudi regime. Financial expenditures coupled with the unpopularity of losing to the less funded Houthi movement reveal the lack of experience and ability of the KSA to engage in a proxy conflict.

Iran is largely perceived as being the aggravating force behind the conflict, although Liebl contends that the Iranian-Houthi relationship is little more than passive and “serendipitous” cooperation. Liebl also argues that the Houthis are not Iranian puppets but Zaydi revivalist/nativists-Yemeni nationalists. Whatever the relationship between Iran and Ansarullah, several authors argue that Iran is risking relatively little for its involvement in Yemen and even more contributors agree that Iran will gain much from an Arab coalition defeat (Ulrichsen, Liebl, Sager). Heightened tensions with Iran is a sentiment that is robustly agreed upon by every author who discusses Iran and a Houthi victory of any kind will only embolden Iranian aggression across the region (Ulrichsen, Feierstein, Ibish and Sager). Iran views Yemen as a highly valuable bargaining chip that it can afford to lose and understands that Saudi Arabia is in no position to retaliate in a meaningful way.

A deterioration of relations between Riyadh and Tehran is one of many reasons why the American interests are threatened by the Yemeni conflict. Ulrichsen, Feierstein, Ibish, Sager, Serwer and Nazer all posit that the US is significantly affected by developments in Yemen but for different reasons. Feierstein and Nazer both emphasize that the U.S. will suffer strategic setbacks with a Houthi/Iranian victory and that a lack of robust U.S. support will severely strain the US-GCC relationship. Both authors also agree that a failure on the part of the U.S. to display overt support in the conflict will lead the GCC nations and Saudi Arabia in particular to seek support elsewhere out of necessity. Another key component at play in the discussion of US interests at risk in Yemen are the counterterrorism operations that will suffer a serious setback if the GCC relationship is called into question. This risk is further heightened by the possibility of Iranian proxies operating without impunity in the Arabian Peninsula.

ISIS, AQAP, and Counterterrorism

Serwer suggests that the US’s main interests in Yemen are counterterrorism and securing passage of trade in the surrounding Yemeni waters. Cragin also emphasizes the negative consequences of the Yemen conflict on American CT efforts and that ISIS and AQAP have and will continue to benefit the most from conflict in Yemen. Ibish also frames a narrative of outcomes that will further fuel extremism and terrorism, namely through inflaming sectarian tensions, continued humanitarian disasters and famine, and lastly a vindication of anti-Western propaganda and disdain. These consequences allow and ISIS and AQAP to further advance their agenda despite their divergent methods and goals in Yemen. Cragin articulates that ISIS and AQAP both ultimately seek to supplant the Yemeni crisis with their sponsorship of revolution and both highly value the strategic nature of basing operations in Yemen. The combined saliency of Yemen and the inherent chaos have provided both terror groups with the ideal platform to extend operations externally from Yemen.

Contributing Authors

Kim Cragin (NDU), Gerald Feierstein (Middle East Institute), Hussein Ibish (Arab Gulf States Initiative), Vern Liebl (CAOCL, Marine Corps University), Shoqi A. Maktary (Search for Common Ground), Fahad Nazer (National Council on US Arab Relations), Abdulaziz Sager (Gulf Research Institute), Daniel Serwer (Middle East Institute), Martin Styszynski (Adam Mickiewicz University), PiX Team (Tesla Government Services), Kristian Coates Ulrichsen (Rice University)

Examinations of Saudi-Iranian Gray Zone Competition in MENA, and of Potential Outcomes of the Flow of Foreign Fighters to the United States.

Author | Editor: Capps, R., Ellis, D. & Wilkenfeld, J. (ICONS).

Executive Summary

The United States is regularly challenged by the actions of states and non-state actors in the nebulous, confusing, and ambiguous environment known as the Gray Zone. Planners, decision makers, and operators within the national security enterprise need to understand what tools are available for their use in the Gray Zone and how to best develop, employ, and coordinate those tools. This report summarizes the results of simulations created and executed by the ICONS Project as part of a larger study to capture at least some of the information needed toward that end.

On October 24, 26, and 28, 2016, under the guidance of the Pentagon’s Office of Strategic Multi- Layer Assessment and the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of University Programs, staff of the ICONS Project at the University of Maryland executed three simulations. Two of these examined competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia in the Gray Zone, both direct and through proxies. The third examined the threat to the homeland of a collapse of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

Participants in the simulations were drawn from various U.S. government agencies and from universities, research centers, think tanks, foreign governments and militaries. Within each of the three simulations participants were given start states and asked to react to events introduced into the scenario. Broadly, the start states placed the participants in mid-2017, about six months into a new U.S. administration. They were told the USG had placed a priority on understanding and shaping the relationship between Iran and Saudi Arabia (in two of the simulations) or in understanding and protecting the homeland against any threat evolving from the competition between Islamic State and Al Qaida (in the third). Play in each of the simulations took place virtually with participants joining via ICONSnet from around the world. Each of the three simulations ran for four hours.

There were five principal take-aways from these simulations:

- It may not be possible for the U.S. to influence or shape Gray Zone activities by other states, especially when those actions are not directed toward the United States. When two states or a mix of state and non-state actors want to engage in the Gray Zone, there may be little the U.S. can do to stop them. Sometimes the only possible action is no action other than planning for likely results.

- Violent extremist organizations may act in the Gray Zone in an attempt to drag state actors out of the Gray Zone. State actors need to have appropriate strategies developed and responses queued for rapid delivery.

- The U.S. is not the sole major power assessing threats and opportunities in Gray Zone conflicts and competitions. It is possible that actions by other major powers could draw the U.S. further into conflicts or drive parties to violence.

- To operate effectively in the Gray Zone, U.S. policy designers and operators need access to every available tool; a whole-of-government approach is crucial to success. In fact, we should begin to think in terms of a whole-of-government-plus structure where government reaches out to non- government regional and technical specialists, subject matter experts, and other “different thinkers” to formulate courses of action.

- Controllers noted a clear bias among the U.S. government participants toward Saudi Arabia and against Iran, and a willingness to move rapidly to kinetic or other military action by some of the military players. Such an overt bias may adversely affect the ability of the U.S. to take advantage of opportunities for influence in Gray Zone conflicts.

Participants in the Iran-Saudi Arabia simulations stated in after action reviews their belief that the U.S. must recruit, train, and deploy the right people with the right skills, including a mix of government and non-government thinkers. There was also a note that the USG lacked a cabinet level information agency dedicated to developing and disseminating the U.S. narrative and to countering enemy narratives.

In their after-action reviews, participants in the foreign fighter scenario focused on the difficulties of developing and maintaining a common operating picture across federal, state, and local entities; on the importance of understanding the roles, capabilities, and authorities of each entity; on the importance of accurate and timely intelligence, and how to share information to best effect across agencies where security clearance levels vary.

Question (V2): What are the key factors that would impact the wave of violent extremism and ideological radicalism that affect the Sunni community?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

The Sunni community is not homogenous, and contributors expressed their discomfort making broad generalizations for a number of reasons. Most Sunni Arabs still consider themselves first a citizen of their respective countries with the exception of populations in the midst of conflict like Iraq, Syria, and Yemen (anonymous). Local customs and histories result in a different experience for Sunnis in, for example, France versus Chechnya (Olidort). Furthermore, there is no single Sunni leader (like the Pope or the Ayatollah or even a senior theologian) with religious legitimacy to assert leadership over the Sunni community (Shaikh).

However, experts attempted to broadly categorize risk factors—especially as they pertain to Sunnis inside and outside Combined Joint Operations Area (CJOA). Unfortunately, the factors most likely to impact waves of violent extremism and ideological radicalization are already well known to the DoD community.

Conditions that Are Conducive to Radicalism and Extremism

Failure of the Social Contract

While particularly true in Iraq and Syria, it is nonetheless applicable across the all societies that when a government breaks its social contract with its people—through exclusion from government, disenfranchisement, failure to provide equitable essential services, justice, or security—unrest often follows (Abbas, Everington, anonymous; Sheikh). ISIL and other extremist groups thrive in these conditions as people who are left with little-to-no legal recourse choose violence. Filling these voids or assisting governments to address these legitimate grievances may reduce underlying root causes of extremism (Olidort).

Failure to Defeat ISIL

Hammad Sheikh, visiting scholar at the Centre on the Resolution of Intractable Conflicts at Oxford University, stated “only when ISIL is defeated in the field unambiguously will the allure of Jihadi ideology be affected.” Establishing a territorial caliphate is at the heart of ISIL’s legitimacy, so striking at that erodes the appeal and credibility of ISIL. This must be done largely by Sunni Arab forces. Atrocities by any other group will incite tribalism and feed into the narrative of jihadi groups, increasing radicalization of the wider Sunni Arab population (Sheikh).

Lack of Resolution in Syria

Atrocities committed against Sunnis in Syria struck a flint to simmering unrest in the region, allowing for the rapid rise of ISIL. The lack of resolution in Syria remains an open wound that continues to attract foreign fighters from across the globe (Olidort). “A complete resolution designed and carried out with the participation of local moderate actors would have the effect of downgrading the allure of foreign fighters and others to migrate to Syria,” Jacob Olidort, an expert on Islamist groups at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy suggested. However, as we have already begun to see, the territorial defeat of ISIL will likely force the organization to change its tactics, encouraging sympathizers overseas to conduct lone wolfs against the far enemy.

Lack of Unified Sunni Political Voice

To combat extremism in CJOA, the USG could facilitate a Sunni Empowerment Campaign (Carreau). This kind of strategy would “create the strongest and most effective antidote to ISIL’s magnetism (including for local recruits and foreign fighters) and worldwide expansion (including lone wolf attacks in the west) because it will finally provide an outlet for Sunni grievances and a viable alternative to violent jihadism as protection against various forms of Shi’a oppression,” according to Bernard Carreau, Deputy Director of the Center for Complex Operations at NDU. This strategy would help build Sunni political voice in Iraq and Syria to help answer the question of who/what should file the void caused by the defeat of ISIL (Carreau).

Perception of Expanded Shia Influence in Sunni Areas

There is widespread belief that the USG is in alignment with Iran to expand Shia influence from Tehran to Damascus. There is certainly mistrust in the ability of the world community to use diplomacy to reach a resolution (Shaikh). While this does not fuel radicalization directly, it influences the decision calculus of Sunnis to build what they see as pragmatic alliances with Sunni jihadi groups who they believe to—at the very least—have Sunnis’ best interests and welfare in mind (Olidort).

This is good news for the Coalition as Sunnis in CJOA may be convinced to turn against ISIL and other extremist groups by appealing to the other “hats” local Sunni leaders wear, such as tribal responsibilities, members of political or commercial elite, the old guard, and other kinds of networks (Olidort, Shaikh). This opens the door to other means of engagement and trust building aside from traditional counter-messaging. In fact, resolutions to challenges facing the Sunni community must remain locally generated to have any real, lasting impact (Shaikh)

Personal Motivations

Finally, Sunnis—particularly outside CJOA—turn towards ISIL and other extremist groups for a number of personal reasons (Everington). Theses range from lack of employment opportunities to discrimination to search for personal meaning (Olidort, Everington, Shaikh). These motivations vary widely from person to person even within the same geographic community and are difficult to address.

Contributors

Hassan Abbas (NDU), Bernard Carreau (NDU), Alexis Everington (MSI), Vern Liebl (USMC CAOCL), Jacob Olidort (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Mubin Shaikh (University of Liverpool), Hammad Sheik (ARTIS)

Author | Editor: Wright, N. (Institute for Conflict, Cooperation and Security, University of Birmingham, UK).

Executive Summary

Understanding and influencing adversary decision-making in Grey Zones requires anticipating key audiences’ perceptions and decision-making. We apply the neuroscience and psychology of human decision-making to help U.S. policymakers produce intended and avoid unintended effects in the Grey Zone.

Key features of the Grey Zone: the centrality of influence

Grey Zone conflict is necessarily limited conflict, sitting between “normal” competition between states and what is traditionally thought of as war. Thus, the central aim is to influence the decision-making of adversaries and other key audiences, rather than removing their capacity to choose using brute force in itself. Success requires moving the emphasis from control to influence.

What, if anything, differentiates the Grey Zone from other types of conflict? The fundamental nature of conflict is unchanged, but the Grey Zone requires different emphases. I summarise these key challenges as the “Five Multiples” of the Grey Zone.

(1) Multiple levels: The U.S. must successfully influence multiple societal levels, namely at the state level (e.g. adversarial, allied or neutral states); at the population level (e.g. mass communication within states and communities); and at the non-state actor level (e.g. proxies, violent extremist organisations or quasi-states like Da’esh).

We systematically evaluate empirical, real-world evidence to identify key cognitive factors for influence at each level. We integrate these into usable tools. For example, a “Checklist for empathy” (Box 2.1) provides a realistic analysis of an adversary, ally and other’s decision calculus, which includes key human motivations such as fairness, legitimacy, surprise and self-interest.

(2) Multiple domains and instruments of power: Multiple domains—e.g. military, information, economic and cyber—cut across these multiple societal levels.

Key cognitive factors can be common or differ between domains. For instance, managing surprise and predictability (concepts incorporated in a simple “prediction error” framework grounded in neuroscience; Chapters 7-8) is critical across domains and levels to cause intended effects and avoid unintended effects.

(3) Multiple timeframes: One must consider at least two separate timeframes: managing an ongoing process evolving over years; and managing short-term crises in light of that ongoing process.

Combating propaganda, conducting information operations and messaging more generally audience. Trust is fundamentally psychological, and trusted messengers can often only be created with over longer timeframes (e.g. the BBC).

We analyse the two biggest historical cases of inadvertent escalation between European powers since 1815: the road to the Crimean War of 1854 in which some 800,000 soldiers died in the Anglo-French versus Russian conflict; and road to the First World War. Both were preceded by lengthy Grey Zone confrontations. U.S. decision-makers must be aware that each episode in the Grey Zone sets the stage for the next interaction. Violating norms, even for admirable reasons, can escalate Grey Zone conflict on a longer timeframe.

(4) Multiple audiences: Ally and third party perceptions are critical in the Grey Zone – and U.S. actions will inevitably reach multiple audiences. For instance, if it lost allied support inthe South China Sea, the U.S could suffer deterrence by ally denial.

Audience analysis is critical across these multiple audiences. This requires both local knowledge within key local audiences, and also the ability of the U.S. analysts to put themselves in the shoes of their audiences – the type of “outside-in” thinking enabled by our Checklist for Empathy.

(5) Multiple interpretations: Ambiguity is a key feature of the Grey Zone. Ambiguity’s essence is that events or actions are open to multiple interpretations. Ambiguity provides an extra layer of uncertainty even before one consider an event’s risk, and can thus directly contribute to crisis escalation. Ambiguity can also help de-escalate crises, for example enabling compromises that save face on both sides (e.g. the “apology” in the 2001 Sino-U.S. EP-3 incident). In the long run ambiguous actions can change behavioural norms and thus escalate international tensions.

Violating Normal: How International Norms Transgressions Magnify Gray Zone Challenges.

Author | Editor: Stevenson, J., Bragg, B., & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc.)

Overview

The current international system presents multiple potential challenges to US interests. In recent years, state actors, especially but not limited to Russia and China, have taken actions that disrupt regional stability and potentially threaten US interests (Bragg, 2016). Many of these challenges are neither “traditional” military actions nor “normal” competition, but rather fall into a class of actions we have come to call “gray” (Votel, 2015). Here we define the concept as: “the purposeful use of single or multiple instruments of power to achieve security objectives by way of activities that are typically ambiguous or cloud attribution, and exceed the threshold of ordinary competition, yet intentionally fall below the level of [proportional response and] large-scale direct military conflict, and threaten the interests of other actors by challenging, undermining, or violating international customs, norms, or laws.” (Popp and Canna, 2016).

Many analyses have focused on the material effects of gray zone actions and gray strategies, such as changes to international borders, or threats to domestic political stability, however few have emphasized the role that international norms play in gray actions and gray strategies, and potential response to them. This paper beings to fill that gap by exploring the normative dimensions of gray zone challenges.

The role of norms in international relations

At the broadest level, norms are rules of behavior that are recognized and understood by a community of nations. In many cases norms go unnoticed until they are violated (Goffman, 1963). International norms represent collective expectations about how other states will act and thus can have significant influence on the behavior of individual actors in the international system. In particular, they can help actors overcome some of the barriers to interstate cooperation. Norms provide solutions to coordination problems (Martin, 1992; Stein, 2004), reduce transaction costs (Ikenberry, 1998; Keohane, 2005), and provide a “language and grammar” for international politics (Kratochwil, 1999; Onuf, 2013). In some cases, such as norms regarding use of chemical weapons or the use of force to change territorial boundaries, norms have been institutionalized and become part of international law. In other cases, such as human rights, international norms reflect widely shared, but not necessarily universal, beliefs.

Among actors in the international system norms provide guidance regarding which behaviors, although not strictly forbidden or illegal are considered unacceptable and liable to censure. Regular compliance with international norms signals that we are dealing with an actor who shares our perspective on how states “should” behave (Shannon, 2000). An actor abiding by relevant norms signals the value it places on those shared standards of behavior, and its intention to play by the established “rules of the game.” Doing so many also increase the willingness of others to engage in political, economic, or security cooperation.

In essence, a pattern of adherence to norms can build trust between actors in an otherwise uncertain system. Trust is “a belief that the other side prefers mutual cooperation to exploiting one’s own cooperation, while mistrust is a belief that the other side prefers exploiting one’s cooperation to returning it” (Kydd, 2005). Trust is important component of understanding the effects of norms violations because that another actor will comply with international norms significantly reduces the kinds of uncertainty that gray zone challenges nurture. As trust deepens, reliance on norms, rather than explicitly stated and formalized rules to regulate behavior, particularly competitive behavior can increase (Bearce & Bondanella, 2007; Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998; Glanville, 2016; Katzenstein, 1996; Klotz, 1995). While international norms are generally understood by states in the global system, we cannot assume that those rules and supporting norms necessarily reflect the domestic values and interests of all states.

Question (R4.3): To what extent is the Iraqi Army apolitical? Do they have a political agenda or another desired end- state within Iraq? Could the Iraqi military be an effective catalyst for reconciliation between different groups in Iraqi society? Could conscription be an accelerant for reconciliation and if so how could it be implemented?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

The subject of this report touches on a critical issue for the future of Iraq as a unified and stable state: To what degree will the Iraqi Armed Forces be able to serve as the vanguard for resurrection of national identity and tolerance? If the answer is not at all, Iraq as a single independent state is likely doomed.

To address the question posed, many of the expert contributors to this Reach-back report begin with an important observation: the Iraqi Army, like other public institutions around the world, is not a unitary actor with a single political orientation, agenda, or desired end- state. Like other militaries, it mirrors the social conditions and pressures of the population from which it comes. For the Iraqi Army, this means the ethno-sectarian divisions, pervasive corruption, and well-ensconced patronage and power networks that work around and despite military rank or process.

How did the Iraqi Armed Forces get to this point?

A number of the contributors point to the turbulent history of the Iraqi Armed Forces (IAF) as the foundation of its current condition. Hala Abdulla of the Marine Corps University dates the beginning of the deterioration of its professionalism and strength to the Saddam Hussein era, when Saddam assassinated senior leaders that he perceived as threats to his control. Over time, this practice meant that the cohort of professional leaders who might have enjoyed broad popular and military regard had been decimated. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by Coalition forces continued the weakening of the Army as an institution. Importantly, that invasion also had the critical effect of drastically changing the sectarian make-up of the Army leadership from Sunni to Shi’a- dominated; a process that was accelerated under the leadership of Nouri al Malaki. Abdulla argues that the post-2003 Army was weaker than the pre-2003 Army reflecting the fragmentation of society, along with rampant corruption and nepotism.

Does the Army have a political agenda? Not exactly.

The contributors to this report each argue that the Iraqi Army is far from apolitical, but importantly, that this fact is the result of the Army’s demographics rather than its partisanship. Dr. Elie Abouaoun of the US Institute of Peace cautions that we take care in thinking of the Army as a “monolith” with a single set of political views. It is because the force is overwhelmingly Shi’a that it naturally reflects the political and social concerns of the Shi’a-led government and communities.

The experts also agree that the Army does not have its own political agenda or cohesive image of the future of the Army or Iraq. Rather than any political orientation in fact, Middle East scholar Shalini Venturelli’s (American University) research identifies the strongest guiding principle in the Army as preservation of individual and group power and influence. This is done in the Army via the same types of social and familial patronage and influence networks found in the rest of the country. It is this urge and the dynamics of competing hidden power networks within the Army that has stymied its re-professionalization and accounts for the corruption and nepotism with which it is plagued.

Could the Army or Special Forces serve as a force for national reconciliation? No way, unless …

There is wide agreement among the authors regarding the prospect that the Iraqi Army could be a catalyst for national reconciliation: they are dubious at best. Wayne White of the Middle East Institute points out that, in its current guise, the “largely Shi’a force sometimes [has been] in league with abusive militias” and, though the Iraqi Army that fought Iran was more than half Shi’a, the years of ethno-sectarian conflict have embittered many in the Army against Sunni, Turkoman, Kurdish, and other groups. Elie Abouaoun (USIP) explains that “solidarity” among some military units might develop, but “the institutional bonding is not strong enough to overcome the vertical divisions along ethnic and sectarian lines.”

The two areas where the experts disagree are: 1) whether the Army’s successful performance in Mosul has rehabilitated its reputation among minority populations; and relatedly, 2) the degree to which the US-trained Iraqi Special Forces (Golden Divisions) that make up a large part of the Mosul force might serve as a model for professionalizing the larger force and catalyzing national regard for the military. Bilal Wahab (Washington Institute for Near East Policy) and Muhanad Seloom (ICSS, UK) believe that the “highly professionalized” Special Forces have “boosted a sense of nationalism” in Iraq and have significantly improved popular perception of forces that not too long ago were seen not as Golden, but as the “Dirty Division.” Yerevan Saeed (Arab Gulf States Institute) and Macin Styszynski (Mickiewicz University, Poland) observe little change in Sunni or Kurdish views of the Iraqi Army, primarily they argue, because these populations observe little change in the Army—which looks very much like the organization until very recently responsible for “widespread abuse, violence and human rights abuses.” Shalini Venturelli (American University) believes that even if there was improved popular regard for the Special Forces, the exceptionalism of the Golden Division is overstated, and that withdrawal of US trainers and support elements would rapidly show these units to be bound by the same corruption and competing power networks as the larger force.

Although highly skeptical of these occurring any time soon, the experts do offer conditions under which the Iraqi Army might eventually serve as an engine of national reconciliation. The most critical of these is (re)gaining popular trust in both the Government of Iraq and the military that serves it. The only way to overcome popular perception of the Army’s Shi’a favoritism is through sincere political reform in which “Sunnis have a major strategic stake” and are convinced of the government’s “enduring commitment to their security regardless of which party(ies) hold the reins of power” (Shalini Venturelli, American U.) Even if there were to be a professionalized, unified Iraqi Army some time in the future, Zana Gulmohamad of Sheffield University forecasts that “the reconciliation will be partial, and not include the entire country,” but instead be limited to Iraqi Arabs (Shi’a and Sunni). The Kurds, he argues, have their own security forces that they will always trust more than the Iraqi Army.

Is conscription a good idea? Not likely.

None of the expert contributors to this report sees conscription into the Iraqi military as a viable path to reconciliation. In fact, some suggest under current conditions military conscription could very easily deepen rather than reduce the ethno-sectarian tensions that wrack the country. While he allows that, “enrolling in the army—including conscription—might ease up inter-personal relations somehow,” Elie Abouaoun contends that the effect does not scale because Sunni “collective fears” of the Army remain. He points to Lebanon’s experience with using compulsory military conscription to encourage national identity among its warring sectarian groups. The failure to enact political reforms, he says, was a major cause of the lackluster results: “failing to embrace an inclusive governance model undermined the possible—though highly unlikely— impact of such efforts. Iraq is not different, especially with the presence of tens of thousands of fighters now enrolled in militias.”3 Again, the military reflects the nation.

The point is this: prior political reform and social integration are not just important facilitators for development and professionalization of the Army and thus its value as a platform for national identity and reconciliation—they are required pre-conditions. Neither the current Government of Iraq nor the Army is likely to succeed in stabilizing the country until Sunni Arabs and other minority populations are integrated into the state’s political, security and social institutions. As Wayne White of the Middle East Institute cautions, if this is ignored, Sunni resistance will persist. Finally, Shalini Venturelli reminds us that, even if these reforms have been made, restoring the trust of Sunnis, Kurds, and other minority groups in the national Army is a decades-long process.

Contributing Authors

Hala Abdulla (Marine Corps University); Dr. Elie Abouaoun (US Institute of Peace); Dr. Scott Atran (ARTIS Research); Zana Gulmohamad (University of Sheffield, UK); Yerevan Saeed (Arab Gulf States Institute); Dr. Muhanad Seloom (Iraqi Centre for Strategic Studies, ICSS, UK); Dr. Marcin Styszynski (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland); Dr. Shalini Venturelli (American University); Dr. Bilal Wahab (Washington Institute for Near East Policy); Wayne White (Middle East Institute)

Approaches to Space-Based Information Services Among Actors Without Space Capabilities. A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.)

What is ViTTa®?

NSI’s Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa®) provides rapid response to critical information needs by pulsing our global network of subject matter experts (SMEs) to generate a wide range of expert insight.For this SMA Contested Space Operations project, ViTTa was used to address 23 unclassified questions submitted by the Joint Staff and US Air Force project sponsors. The ViTTa team received written and verbal input from over 111 experts from National Security Space, as well as civil, commercial, legal, think tank, and academic communities working space and space policy. Each Space ViTTa report contains two sections: 1) a summary response to the question asked; and 2) the full written and/or transcribed interview input received from each expert contributor organized alphabetically. Biographies for all expert contributors have been collated in a companion document.

Question of Focus

[Q4] What insight can the US/partners obtain from the space-based information service approaches used by international actors that lack their own space capabilities?

Expert Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James B. Armor, Jr.2 (Orbital ATK); Mark Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Caelus Partners, LLC; Faulconer Consulting Group; Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson (USAF Air Command and Staff College); Gilmour Space Technologies; Dr. Namrata Goswami (Auburn University Futures Lab); Harris Corporation, LLC; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); ViaSat, Inc.

Summary Response

The experts’ responses to this question suggest two main insights the US can draw from how actors without space capabilities approach space-based information services. The first relates to the information these actors are seeking: what it indicates about their interests and the potential security implications access to that information has for the US. The second relates to the strategies these states are using to gain access to space-based information, in particular collaboration and reliance on private sector services.

Interests

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor’s3 response to this question focuses on the observation that what actors choose to buy can provide insight into their interests. Consistent with this, the Faulconer Consulting Group, focusing their response on international actors as customers and/or as potential combatants, highlights the potential benefit to the US that knowledge of the service provider satellite type and capability provides. Specifically, it would enable the US to ascertain what type of information is of interest to other actors and thus draw conclusions “as to the need for that type of data/information and its attendant purpose.” Dr. Namrata Goswami from Auburn University Futures Lab identifies Luxembourg, UAE, Israel, and Iran as states that have all shown interest and capability in using insights drawn from space-based information services.

Security Implications and Threats

Mark Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin and Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson of USAF Air Command and Staff College both consider that the increased access to data that space-based information services provides raises security issues. The availability of high-resolution imagery from commercial providers combined with customized data-analytics makes it possible for actors to track military activities and capabilities as well as non-military factors, including those that could be used to manipulate economic stability (Garretson), without needing their own space capabilities. Berkowitz suggests that space-based information services can provide the US with insight into threats to intelligence sources and methods, force protection and operations security, as well as countermeasures to mitigate those threats.

Opportunities for Collaboration

Data sharing

Dr. Goswami suggests that India’s sharing of satellite services with countries like Bhutan, Bangladesh, Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Nepal could be used to mitigate disasters and detect weather patterns, much as the UN does with its UN-SPIDER space-based information systems. She suggests that countries like the US and India could collaborate in similar data sharing to build disaster mitigation capacity. Consistent with this idea, Caelus Partners suggest “that the US consider providing additional space services and support to all of humanity (as is done with GPS).” They contend that “[c]ertain space-based information services are a basic necessity to operating effectively on Earth.”

Capability enhancement

Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland states that reliance on outside providers enables states to gain capabilities faster than they can through domestic development, thus resulting in more up-to-date technology. Furthermore, states currently developing space-based infrastructure have a variety of potential partners to choose from, and thus a wider range of capabilities to choose from. The ViaSat team notes that a similar logic applies to the US/partners, where private sector satellite services are faster to develop and deploy than are government systems, and result in more flexible architectures that allow for “near-instantaneous response to continually evolving cyber threats and related security concerns.” Leveraging private sector services enables international actors that lack their own space capabilities to rapidly improve their capabilities at a fraction of the time and investment of US/partners. Further, without adherence to installed base solutions, these international actors can adopt so rapidly that they could potentially surpass US/partner capabilities.

Dr. Goswami notes that Iran, UAE, and China all jumpstarted their entry into space activities through partnerships with countries with more advanced space program and capabilities. The effectiveness of this strategy for China is reflected in the fact that it is now offering its own Beideu2 navigation systems to countries along the One Belt One Road (OBOR).4 In its contribution, Harris Corporation suggests that utilizing others’ space services also allows actors to benefit from “lessons learned,” making their own choices more cost effective.

Brigadier General (USAF ret.) Tom Gould of Harris Corporation suggests, however, that security considerations may limit the potential for such collaboration in support of military operations, as it will require sharing sensitive information about each other’s capabilities in a domain that has traditionally stove-piped or highly classified its capabilities.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Question (R4.9): What are the medium to long term implications to US interests and posture of China’s economic, diplomatic and military expansion into South Asia, Middle East and Africa?

Author | Editor: Hayes Ellis, D. (University of Maryland).

Executive Summary

“It’s the Economy Stupid!”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, all the contributors to this question devoted attention to the outsized role economics—and especially the quest for natural resources—plays in the Peoples Republic of China’s (PRC) relationships in the MENA region. In general, the consequentiality of this factor trends negative when assessed through the lenses of either a) US policy goals or b) global liberal economic norms. Chow, for example, characterizes the failure of the US to more aggressively push back on manipulative PRC trade practices as “carelessness” and “empty rhetoric.” He also sees a direct line between the perceived cave-in on Washington’s part and Beijing feeling empowered to seize the initiative in other areas detrimental to US interest, such as increased militarization and aggressive behavior in disputed territorial areas.

Holslag points to a whole different array of challenges, identifying various ways in which the style of PRC economic engagement with developing nations and oil-states encourages those countries to behavior that is counter to western, liberal free-trade norms. He also makes a link directly from economics to geopolitics, claiming China’s economic statecraft “undermines Western economic and political influence.” Serwer and the editor both concur on a convenient shorthand from economic theory, labeling the PRC’s trade behavior essentially mercantilist—that is to say, viewing the world as a zero- sum-game with finite resources, in which a state-directed trade policy is built to benefit strategic national goals—as opposed to the profit and innovation oriented capitalist global order that has defined international norms since the end of the Cold War. However, Chow pushes back against the utility of characterizing China’s behavior as purely mercantilist. He notes that China’s actions are not significantly different than French or Italian investments in the MENA region; the “real difference for US interest is France and Italy are allies and China is seen as a rival.”

Going back to Holslag’s assertion that China’s behavior is generally counter to western, liberal free-trade norms, he bounds his analysis neatly with two hard statistics:

- China’s share in regional investment stock has increased almost ten fold in the last 15 years, while that of the US has declined and

- the PRC is the largest creditor in the region—most of it in concessionary loans.

As he concludes, and the editor agrees, this has had the effect of increasing favorable views of future trade and FDI relationships with Beijing, while dimming the view of Western partners.

Finally, the “One Belt One Road” initiative to recreate both an overland and a maritime modern “silk road” must be mentioned. This framework is the clearest articulation of Beijing’s desire to tie infrastructure investments in trade partners directly to an enhanced geo-strategic position for the PRC. The degree to which the proposed elements of “One Belt One Road” can be realistically executed, versus its role as a piece of symbolic rhetoric delineating Beijing’s policy position, is open to debate.

Rising Powers – Be Careful What You Wish For

The contributors also find agreement on the fact that an increasing role for the PRC as an economic, political, and perhaps security player in the MENA region actually drives towards more adherence to the status quo—not away from it. The editor would point out that a theoretical debate has been raging in political science for some years about the extent to which the PRC is a disruptive power that wants to supplant the global order, versus the degree to which it will accede to existing institutions and norms as it grows into a leadership role. In general, the contributors tend to highlight evidence of the latter perspective. Beijing’s incentives in the MENA-South Asia region are largely meant to function as a status quo power when it comes to the international security regime—further destabilization and political violence is very much counter to the interests of the PRC. There is some irony that the mercantilist economic approach reinforces the same goal as that of the liberal international order, but it should not be overlooked. This may be one of the few regions in the world where PRC-US cooperation toward mutual goals is the obvious first-choice policy for both sides.

Holslag and the editor both highlight one particular set of interest as an especially salient example of these dynamics: the issue of PRC citizens living abroad in the region. Historically, the Chinese state’s relationship with its cultural diaspora has been defined as a kind of formal separation. Indeed in Mandarin, “overseas Chinese”—those ethnic Chinese living outside the mainland—are referred to using a different word from ethnic Chinese people living in China.1 This idea of residence on the mainland defining belonging to the Chinese state is very culturally ingrained, and the PRC is now truly entering an era where it may become a challenge that shapes Beijing’s behavior in the MENA-South Asia region. No modern Chinese government has had to contend with the idea that large groups of its own citizens would be living in far flung locales, but still expect the protection and benefits conferred by being “Chinese.” The model for the last few hundred years has been that those Chinese who opened laundries in California, sugar plantations in the Philippines, or fishing operations in Singapore, were on their own. The PRC can no longer operate that way, and much remains to be seen about how that will shape their behavior when Chinese citizens abroad (especially those working on state-backed projects) come under threat of violence, persecution, etc.

Two significant, concrete signs that Beijing’s reflex response to this problem is to sign up for the normative international order: 1) the decision to finally subscribe to the United Nations “Responsibility to Protect” or R2P framework and provide personnel to peacekeeping missions and 2) the deployment of Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) ships to the Indian Ocean to run shipping convoys during the height of the Somali piracy threat—to date the PLAN’s furthest deployment, and a clear contribution to a massive international effort to protect global trade. Both indicate a recognition by the PRC that the existing international framework helps everyone by recognizing a state’s rights to protect its citizens anywhere in the world, and encouraging all countries to pitch in to keeping that a viable option.

Outside the Box Thinking

In her contribution, Janet Breslin-Smith identifies a possible area of strategic gain for the US stemming from the increase in Chinese economic dominance in the region. She points to the general lack of cultural affinity between regional communities and the Chinese, and suggests that as the PRC comes increasingly to be identified with economic opportunity and investment, so Beijing may also come to bear an increasing share of blame and disgruntlement for what’s not going right. “In a counter-intuitive way” she says, “the healthiest consequence of expanded Chinese interaction in the Middle East would be a recasting of the tension in the narrative of ‘Islam versus the West’ to ‘Islam versus the East. And in that new Chinese/Islamic interaction, an interesting reality emerges.”

Additionally, the editor would seek to add an important caveat to the economics analyses of the other contributors: mixed in with the regrettable elements of the way the PRC tends to structure investment in the developing world are nevertheless some real benefits. Chinese firms are building infrastructure, the Chinese government is pouring money into impoverished governments. It is the editor’s opinion that too often the reflex of US perspective is to view being displaced as the number one as unambiguously negative. Given the failure of the Western world to make so many of the investments in developing countries in the MENA region that are garnering praise for Beijing, one wonders if that’s not a stilted point of view? The overall evidence from 150 years of political science is that a richer, more developed world is a safer one—so from one point of view, the US should welcome Chinese investment in MENA and South Asia, and view it as burden sharing rather than competitive displacement. The US should seek to engage the PRC in defining norms for investment outcomes that promote the long-term economic health of the region and mitigate the negative potential outcomes foreseen by the other contributors.

Contributing Authors

Edward Chow (Center for Strategic and International Studies), Devin H. Ellis (University of Maryland), Jonathan Holslag (Free University of Brussels), Daniel Serwer (SAIS, Johns Hopkins University), Janet Breslin Smith (Crosswinds Consulting)

Author | Editor: Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The Senturion Modeling Project Noor video provides a brief overview of the Senturion modeling and simulation effort in support of the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) team’s Project Noor. For more information on Project Noor itself, please visit: Project Noor Video