SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

[Q3] What are the motivations of nation-state and non-state actors (e.g., violent extremists, etc.) to contest use of space in times of peace, instability, and conflict? What are the political, military, environmental, or social costs associated with acting on those motivations? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. John Stevenson (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

Subject matter experts generally agreed that there were multiple motive pathways for nation-states to contest use of space. These pathways were:

- the vulnerabilities and sensitivities that come from increasing cross-domain dependence on space systems;

- the national pursuit of space programs as a form of (major power) prestige and status; and

- the yet unresolved rules about how to project national sovereignty into space.

Experts also agreed that there are very high costs associated with acting on any of these motives, although they disagreed on whether high costs increased or decreased the likelihood of conflict.

Motivations to Contest the Use of Space

Experts proffered three baskets of motives for why an actor would contest space: space domain dependence, the prestige of space capabilities, and the lack of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

The Vulnerability of Terrestrial Components from Space Domain Dependence

Dr. Malcolm Davis of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute observes that “space systems are vital to the functioning of the US economy and society.” In addition to the economic importance, Dr. Davis notes that space systems also are the bedrock of a “Western way of war,” which “exploits precision, high operational tempo, and joint military operations.”

The ViaSat, Inc. team concluded simply that “the most easily identifiable motive of nation-state and non- state actors against space ecosystems…is to disrupt military command and control.” In other words, the centrality of space systems to the United States’ economic and military operations makes those systems an attractive target for adversaries of the United States seeking to gain terrestrial advantages. Colonel Timothy Cullen5 of Air University warns that adversaries would target space systems “to punish the US and its allies economically, to demonstrate the vulnerability of US and allied space weapons or communications systems, to simply test the effectiveness of unfriendly actions, or a combination of all the above.” Targeting assets in the space domain is one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce US military and informational advantages, according to Dr. Namrata Goswami of Wikistrat and the Auburn University Futures Lab. Dr. Goswami notes, “During conflicts, space based assets like military satellites could be taken down by an adversary to deny precision guidance to missile systems, jam early warning for incoming missiles, and deny data and information on enemy positions. Non-state actors with access to space based capabilities could utilize it to deny access to data like jamming GPS, and reconnaissance.”

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor6 highlights that “extremists” who are not dependent on space would risk targeting assets in space to harm terrestrial components that are dependent on space systems. Rather than “unsung nations” looking for prestige, the main risks of conflict in space stem from the “unplugged actors” looking to level the playing field. Theresa Hitchens, of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, buttresses this view that disconnected extremists— which she refers to as “outliers”—are the likely sources of contestations in space: “I don’t see any motivation for anyone, with North Korea being an outlier because who knows what their motivations are, in actually harming space as an environment because there’s too much social and economic and military benefit coming from space for anyone to really want to contemplate ruining space for everybody else.”

The Prestige of Space Capabilities

Dr. Deganit Paikowsky of Tel Aviv University proposes that “space capability became (and still is) an important mark of great powers.” Space capability, therefore, is a marker of status and influence in world politics. It provides tangible and intangible benefits; as such, it is also a source of prestige. Sergeant First Class Jerritt Lynn,7 United States Army Special Operations, observes: “International prestige was a factor during the space race, and it continues to be one as other states are pushing their way into the international spotlight.” Similar prestige motives animate China’s national space program, according to Lynn: “China just recently finished construction on the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) in Pingtung. This is currently the world’s largest radio telescope…As the international scientific community uses this platform, it will garner international prestige, grant the opportunity to conduct cutting-edge research, and aid in China becoming a global leader in the space

and science community.”

Prestige motives, however, are not necessarily identical to the motives to contest other countries’ use of the domain in which prestige is pursued. In the space domain, these motives for great power status are part and parcel of the motives to contest, experts argue, because of the dual-use nature of space systems. Dr. Gawdat Bahgat, of National Defense University’s Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Study, notes that this dual-use is the source of space programs’ prestige: “A space program consists of satellites and communications infrastructure—it has many civilian uses. This is why space programs are still prestigious.” The dual-use nature of space systems means that any pursuit of advantages in the space domain has major cross-domain implications for the relative strength of various instruments of national power.

Prestige motives can play out regionally or globally. Dr. Martin Lindsey of US Pacific Command characterized regional factors as being the chief drivers of the dynamics of national space program development in the Asia-Pacific: “There are various space races going on in the Asia Pacific region—the big ones being between China and India, and then to a lesser degree between China and Japan, and these are more tied up in nationalism and global prestige.” The interplay of the pursuit of prestige and the cross-domain effects of increased space capability leads Brett Biddington of Biddington Research Pty, Ltd to lament: “I would say that I think that war is already on in space—it’s just not declared…The profound issue here is, of course, that almost everything we do in space is dual-use or can be badged as being dual-use.”

Pursuit of Sovereignty Claims in the Context of Unclear/Unsettled Rules

Our experts generally agreed that only certain actors would have the means and the motive to contest the use of space. That current set is generally the “Big Three” space-faring nations—the United States, Russia, and China—although Dr. Bahgat also included India as a major space-faring nation.

Dr. Goswami posits that the “lack of international regulatory framework that could adjudicate and establish ownership, a dispute may break out during peace time.” Dr. Bahgat provided the most succinct summary of the four potential goals that might lead space-faring nations to contest countries’ use of space:

- Achieve space domain capability and advantage vis-à-vis adversaries by investing in research and development.

- Stake territorial claims in outer space once humanity cracks the code of mining precious metals on the lunar surface and beyond.

- Support growing commercialization of space activities and an emerging lucrative market for space based activities.

- Build military capacity based on space based assets to sustain the trade links and establish superiority on earth.

Of these four goals, the latter three relate to how the lack of rules about how to articulate sovereignty in space also can lead these (generally sovereignty-obsessed) space-faring nations to contest the use of space.

Costs Associated with Contesting Use of Space

Of the subject matters experts who explicitly advanced a view of the costs of contestation, all were in agreement that contested space operations are very expensive and have hard to anticipate second- and third-order effects. The subject matter experts from ViaSat, Inc. suggested that contesting the use of space could occur in any domain, since the space ecosystems exist in multiple domains, and the means would likely be the least attributable, most detrimental, lowest cost approach considering all the ecosystem domains.

In general, contributors to this response suggested three distinct reasons why contested uses of space, in space, would be (potentially prohibitively) expensive:

- The novelty of space contestation, according to Christopher Johnson of the Secure World Foundation, means that: “Interfering with or hacking a space object would be a new, unique, ground-breaking activity and would therefore be a nefariously prestigious accomplishment unto itself.”

- Dominance in space is fleeting given the technological potential of industrialized countries, making a thorough cost-benefit assessment unreliable. Colonel Cullen observes that “dominance in space may not be possible against aggressive and industrialized nations, regardless. It is difficult to express how expensive the net cost of the development and large- scale employment of even ‘low cost’ access to space will be or how unforgiving, harsh, and costly the space environment is to conduct operations, and the space industry has little incentive to state their net estimates either.”

- The domestic politics of the militarization of space, especially in societies with stark inequalities in income and wealth, is a tricky set of optics for national elites to manage, as Dr. Goswami discerns: “The desire to create space domain advantage would require budgetary allocations, thereby taking away limited resources … from their poverty alleviation programs. This could create a backlash in society thereby raising questions about the feasibility of such outer-space motivations.”

In conclusion, the costs associated with contesting other countries’ use of space, in space, is extremely high, while the cost to contest a space ecosystem in its ground or cyber domains could be much less. Although many experts thought that the costs to a country’s own space assets make contestation in space too risky for most space-faring nations, they did agree that the same nations possessed multiple motives that could lead them to consider it. In addition, if a nation state or non-state actor “considered” contestation, they may also consider targeting the space ecosystem in a non-space domain.

The motives to do so stem from: the vulnerabilities and sensitivities that come from increasing cross- domain dependence on space systems; the national pursuit of space programs as a form of (major power) prestige and status in the context of dual-use space capability; and the yet unresolved rules about how to establish sovereignty space in an environment with increasing demands for stable commercial and/or national property rights in space.

Contributors

Brett Alexander (Blue Origin); Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Dr. Gawdat Bahgat (National Defense University’s Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Study); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Brett Biddington (Biddington Research Pty Ltd, Australia); Caelus Partners, LLC; Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (ret.) Deron Jackson (USAFA); Colonel Timothy Cullen, Ph.D.3 (School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, Air University); Dr. Malcolm Davis (The Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Australia); Faulconer Consulting Group; Dr. Namrata Goswami (Wikistrat and the Auburn University Futures Lab); Harris Corporation; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Christopher Johnson (Secure World Foundation); Dr. Martin Lindsey (US Pacific Command); Sergeant First Class Jerritt A. Lynn4 (United States Army Civil Affairs); Colonel David Miller (United States Air Force); Dr. Deganit Paikowsky (Tel Aviv University); Dr. Edythe Weeks (Webster University and Washington University, St. Louis); ViaSat, Inc.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Question R5.4: How should United States foreign policy evolve in the region post-Islamic State of Iraq and Syria? What are the dynamics in the region and what will be the implications of this for the USG?

Author | Editor: P. DeGennaro (TRADOC G-27) & S. Canna (NSI, Inc,).

Executive Summary

US foreign policy makers struggle to find the right balance in supporting US interests in the Middle East (Abdulla, Bahgat, DeGennaro, Liebl, Maye, Rogers, Serwer, Styszynski). The unbalanced policies, those focusing solely on defense or certain allied interests, while marginalizing diplomacy and development, are diminishing trust in the US and decreasing its influence—challenging US ability to maintain global stability.

Historically, US interventions in the region have caused instability and competition between regional Middle Eastern states leaving many of the weaker parties—Libya, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Yemen, and the Palestinian territories—targets for interference from the Arab Gulf countries, Iran, violent extremists, and those who thrive on internal conflict (DeGennaro). As a result, the region, and more recently the world, has been plagued with ideological radical extremists who have used a perverse form of the religion of Islam to violently project their discontent and anger on populations. Despite US efforts to counter extremist influence and diminish VEO capabilities, the chaotic ungoverned environment allows them to remain or go underground (Liebl, Rogers). Experts agree that the Islamic State, although severely diminished by the Iraqi coalition offensive, will not completely disappear, but only weaken (Abdulla, Cammack, Liebl, Maye, Rogers) and continue to reemerge in the region and abroad. Much of Iraq’s potential to survive beyond ISIS will depend on continuing down the stability/democracy building path, one that can hold hope for Syria, and US engagement with groups that exhibit similar goals/values should be encouraged (Meredith). Now that the Islamic State as an organization is damaged, the US should not become complacent (Cammack, Liebl, Maye, Rogers, Styszynski). The US must strategically revise its foreign policy in the region based on desired outcomes and, at the very least, define US interests in the region internally (Meredith). The previous and still ongoing lack of US policy clarity hampers commitment to US actions from stakeholders. Countries and non-state actors, allies, and adversaries alike, are likely to hedge their bets when asked to partner with the US until it becomes clear that they will gain from that partnership, or at the very least not get burned by it; much of this will be defined by the partnership with SDF as a test case for further partnerships in the region (Meredith). The current Administration has not publicly defined its foreign policy in the region or its preferred outcome; therefore, our analysts believe it is necessary to focus on stability (Abdulla, Maye) in the form of free flow of goods (oil among others) and deterring the rise of a hegemonic power in the region, as well as governance legitimacy as a precursor to stability (Meredith). They strongly encourage a broader strategy based on economic and diplomatic influencers keeping in mind not only regional but international stakeholders such as Russia, India, and China (Meredith). The need to partner with groups who develop and mature viable governance capabilities with US support, as compared to the growing divides with regional powers Turkey and Saudi Arabia, should also be emphasized (Meredith).

Looking at the current operational environment, analysts generally agree that the US’s main threats are the resurgence of the Islamic State, a weak and ungoverned or poorly governed Iraq and Syria, continued overreach by Saudi Arabia—supporting extremist groups, continued destruction of Yemen, and unwanted interference in Sunni countries under the guise of balancing Iran and the continued use of proxies by so many stakeholders.

Iran has been able to expand its influence more tangibly through Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon by assisting the Syrian and Iraqi government against opponents and terrorist groups, which could be an opportunity for the US or a threat depending on how the US decides to engage (experts from Global Cultural Knowledge Network). Two schools of thoughts have emerged with one calling for engagement with Iran while others focus on continuing efforts to restrict Iran’s influence in the region. These are historic approaches that should be evaluated more deeply through comparative case study research from the scholarly community.

In the first school of thought, analysts are asking more questions about the existing US relationships with Iran and Saudi Arabia (Bahgat, DeGennaro, Rogers). It is not clear to them why the US is so opposed to, at the very least, some engagement with Iran. Iran has extensive economic potential and diversity. Further, Iran holds the largest gas reserves in the world coupled with vast oil assets. This school of thought suggests that perhaps it is time to warm relations considerably with Iran and cool relations with the Gulf States or these proxy battles will ensure there is no end to the conflicts there.

The second school of thought strongly supports continued US and Coalition efforts to restrict Iranian influence in the region while continuing to develop existing relationships with Gulf States (Cammack, Maye, Serwer). In particular, Maye suggests US policymakers “thwart political infiltration from Iranian- leaning militias and religious leaders” in Iraq and Syria. While Cammack does not view Iran influence as a strategic threat to US interests, its negative impact on regional stability suggests that the US use diplomatic efforts and strategic patience to reduce it.

Regardless of approach, analysts believe that the US must be clear about its mission and intentions in the entire region, and assess the tools and levers of influence for better governance and economic progress that can help to reduce the tendency to move toward dangerous ideological movements. With a weak or ad hoc policy that continues to remain unclear to both US allies, service and coalitions members, adversaries and people in the region, the US is losing its ability to influence, especially in light of growing Russian alternatives to traditional and emerging US partnerships (Meredith).

Before the policy questions are answered it will be difficult for military to do much more than finish the fight to defeat the Islamic State, which will not eliminate it but provide a window for it to continue to dissipate or resurge in a conflict ridden environment.

Contributors

Hala Abdulla, Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University; Gawdat Bahgat, Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University; Perry Cammack, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Patricia DeGennaro, TRADOC G27; Vernie Liebl, Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University; Diane Maye, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University; Spencer Meredith, National Defense University; Paul Rogers, Bradford University; Daniel Serwer, Middle East Institute; Martin Styszynski, Adam Mickiewicz University; TRADOC G2 Global Cultural Knowledge Network (GCKN)

Question (R4.6): What are the competing national interests of the United States and Iran in the Middle East and what are the options for alleviating United States / Iranian tensions to mutual satisfaction and improved regional stability?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

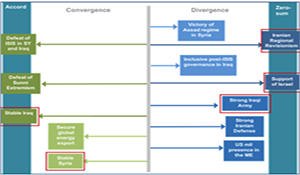

The US and Iran have the same types of interests — national security, international influence, economic, and domestic political—at stake in the conflicts surrounding Iraq and Syria. However, the different ways that each country currently defines these interests places them on a continuum that ranges from full accord over select regional issues to complete, zero-sum discord. This is an important point and one very pertinent to the question of alleviating US-Iran tensions: Iran and the US do not disagree on everything and national security is not always the primary issue at stake. The most promising avenue to alleviate tensions therefore may be to focus on issues on which US and Iranian interests tend to converge. However, there may be more leverage over what seem to be fully divergent interests than at first appears.

Convergent Interests: Stability in Syria, Stability in Iraq

Regardless of current US policy, the defeat of ISIS, followed by relative stability in Iraq and Syria are in the interests of both Iran and the US. For Iran, there are potentially huge post-conflict reconstruction contracts in the offing in Syria, provided the Syrian regime is friendly or weak enough for Iran to control a large part of that business. The earnings could be a boon for Rouhani and the moderate leadership in Iran who had promised yet-to-be-see Iranian gains following the Iran Nuclear Deal (JCPOA). US security interests in the region also are not served by instability in Syria, even if this means abiding by a weakened Assad regime for the immediate term.

Diverging Interests: Strong Iraqi Army

The strengthening of the Iraqi Army is a contentious subject between the US and Iran. The US would like to have influence in Iraqi military institutions, as would Iran. The ideal outcome for the US appears to be a professionalized Iraqi military strong and capable enough to secure its borders, maintain internal stability, and clamp down on radical extremist organizations in Iraq and elsewhere. While it is in Iran’s interests to see a security force in Iraq strong enough to maintain internal order and put down any resurgence of Sunni extremism, an Iraqi force strong enough to pose a threat outside Iraq’s borders is something no Iranian leader likely could or would support. The horrors and trauma of the Iran-Iraq War are still in the vivid memories of a good portion of the Iranian population.

Complete Divergence: Regional Security and Israel

Probably the most rigid points of conflict in US and Iranian interests involve how each defines regional security and, as a result, which actions and actors it perceived as threatening. Iran scholar, Dr. Payam Mohseni of Harvard University, identifies two security issues that serve as “the cornerstone” of US-Iran antagonism: “revisionism for the security architecture of the Middle East” including eliminating US military influence in the Middle East following ISIS defeat, and support of or opposition to Israel.

Iranian Revision to Regional Order.

Iran has long had a goal of changing the power dynamics in the Middle East region. This serves multiple Iranian interests simultaneously and shapes the policies it pursues. First, from the Iranian perspective, expanding its reach via Shi’a groups in Iraq, the Gulf, and Lebanon is an important means of defending Iranian security in a region in which it is a minority. Considering what Iran perceives as its main security threats (e.g., Saudi Arabia and Israel—both backed by US force), together with a desire for regional recognition and prestige, explains Iran’s attachment to a nuclear program. Revisions to the current system that enable Iran to exert additional regional influence and establish additional economic ties also serve the domestic objectives of the more moderate political and commercial elite.

Israel.

Ironically, relations with Israel serve the US and Iran in similar ways. Support for Israel is a consistent element of US foreign policy and is very much tied to US electoral politics. Since the Iranian Revolution, the Government has used its strong opposition to the security threat posed by Israel and the West to garner domestic approval and underscore its break from the Iran of the past (i.e., its revolutionary bona fides) to enhance its (self-proclaimed) legitimacy as the regional protector of the Muslim people.

Both Iranian and US security concerns are indelibly intertwined with the desire of each to increase regional influence and prestige, and to some degree, domestic support. An argument can be made that this coupling of interests is what generates the zero-sum quality of the US and Iranian positions and makes mutual animosities so easy to ignite. A situation perceived as zero-sum, “I win-you lose” by definition is one in which mutual gain is not possible; antagonism is assumed. As a result, all action by the opponent is perceived as competitive and, in the strategic sense, the only options available to each side are opposition or capitulation.

At present, both US and Iranian policy-makers imagine the regional expansion, influence, and attempts to change the regional order by and of the other as important threats to their own security and prestige. In this context, a perceived security gain for the US or its allies, for example by increasing the presence of US forces in the region or inking a $110 billion weapons deal with Saudi Arabia, inevitably is a loss for Iran. Similarly, an Iranian gain, for example increased influence within the Shi’a-led government in Iraq; professionalization and institutionalization of “mini Hezbollahs,” or IRGC clones in the Iraqi armed forces, is seen in the US primarily as Iranian aggression.

Can tensions be reduced? No. Not without reconceiving the US approach

Fortunately, the zero-sum nature of US and Iranian perspectives on these critical issues is not a mathematical absolute (as suggested by the term). Rather, US decision makers interested in alleviating tensions with Iran must recognize that the intractability in how the US and Iran have conceived of regional security is a psychological construct, in large part based in mutual uncertainty about what the other will choose to do. While it may require considerable cognitive and perhaps emotional effort to accomplish, reconceptualizing how the US approaches Middle East regional security and Iran’s role in it is very possible.

Mohseni emphasizes not just the possibility but the urgency of making these changes in US thinking. He argues that changed and changing conditions in the Middle East now demand rethinking of US interests in the region and the threats that it perceives from Iran: in “today’s increasingly fractious and unstable Middle East, it is all the more important to understand where and how the United States and Iran can see eye-to-eye.” He strengthens this argument with the discerning observation that even if the US were to succeed in containing Iran and eliminating the security threat that Iran poses to US allies in the region, some of the most pressing threats in the region, like the spread of violent jihadism and insurgency and political instability in traditional US allies, will remain. Critical threats to US interests and allies will not be mitigated by weakening Iran. This new context requires new thinking.

How? Small steps

If not seeing completely eye-to-eye, alleviating tensions essentially means that diverging Iranian and US interests are moved closer together; toward convergence. Each of the contributors suggests that this can only happen via direct engagement with Iran, which is essential not only for alleviating US-Iran tensions, but indeed for defending the US’s own security interests in the region. First, Dr. Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins SAIS) argues that US-Iran tensions cannot be overcome in a bilateral setting, but instead that a regional security architecture that could help reduce tensions among other regional actors and on other issues (e.g., Sunni-Shi’a competition) is needed. In a similar vein, SFC Mark Luce (USASOC) suggests using diplomacy to reduce Iran’s isolation by, for example, opening dialogues with Iran and Russia on Afghanistan and counter-VEO activities, encouraging others to expand diplomatic and economic relations with Iran, and providing US security guarantees to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states in the event of Iranian aggression. While negotiating these arrangements certainly would require time and significant US domestic and regional resolve, other experts suggest more tactical and short- to mid-term steps for initiating US-Iran cooperation. Specifically, Dr. Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (Visual Teaching Technologies) and Dr. Alex Dehgan (Conservation X Labs) cite the value that Iran has historically put on science, and suggest scientific exchange particularly on water, food, and energy issues. They note that Iranian scientists already “co-author more scientific papers with US scientists than with scientists of any other country,” and that US-trained STEM scientists serve in key positions in the Iranian government.

Contributors

Alex Dehgan (Conservation X Labs); Mark Luce (USASOC); Payam Mohseni (Harvard University); Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (Visual Teaching Technologies, LLC); Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, SAIS)

Media Visions Of The Gray Zone: Contrasting Geopolitical Narratives In Russian And Chinese Media.

Author | Editor: Hinck, R., Kluver, R. (Texas A&M University) & Cooley, S. (Mississippi State University).

Executive Summary

The purpose of this effort was to contribute to the Strategic Multilayer Analysis by examining media messaging strategies in Russian and Chinese language media, in order to uncover the role of media narratives in the development of potential conflict scenarios, narrative trajectories that might minimize or maximize the potential for conflict, and the role of high impact episodes in evolving media discourse. The study was built upon two prior year-long studies of geopolitical narratives in Chinese and Russian media conducted by the research team, and we used the conclusions of those previous studies to provide a starting point for this project. This project has sought to gain an in-depth look at Chinese and Russian media strategies in the context of gray zone conflict and the role of those narratives and techniques in signaling geopolitical intent. These findings are then used to generate potential strategies for minimizing conflict narratives and strengthening cooperative narratives in areas where there is geopolitical strain.

The research team conducted comprehensive studies of national media to uncover shifting messaging strategies, narratives, and metaphors that imply, precipitate, or minimize conflict. Drawing upon close to 50 different Chinese and Russian sources , the researchers identified thousands of news items that contributed to the final analysis. The researchers monitored general news trends and narratives in Russian and Chinese media, and conducted specific issue data pulls in Chinese and Russian. Specific data pulls focused on the visit of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte to the People’s Republic of China, the impact of migration (specifically refugee flows), and coverage of the US Presidential election. The Duterte visit was examined because of the ways in which coverage and analysis of that event revealed narratives of US national decline. The 2016 election was included because of the centrality of that process for global discussion on the value and relevance of US political processes and values in global leadership. In addition, several other data pulls related to ongoing geopolitical events were included because of the insight they provide for reflecting on narratives of collaboration and contradiction.

This analysis presumes a media-centric theory of gray zone conflict, that media narratives have a primary role in creating the political and cultural context in which relations with other nations are created. Media (in both traditional and new media formats) has perhaps the greatest role in shaping and disseminating narratives of conflict, cooperation, and those gray spaces in between, as it provides the geopolitical worldview, as it were, to justify specific policies and stances. Finally, the study utilizes the “narrative paradigm,” a framework for understanding the power of narratives in political contexts, for discussing potential ways to undermine narratives of conflict.

Overall, the findings of this study reveal that both Chinese and Russian media present narratives that feature the decline of the US in economic and political influence, as well as a rapid disintegration of US political values. Russian media narratives, however, are far more critical of the US and the global order than are Chinese, and are typically more confrontational than are Chinese narratives. In the coverage of Duterte’s visit to the PRC, for example, Chinese media was cautious in attempting to capitalize on the Philippine President’s well-publicized “break” with the US, without antagonizing the US. Russian media coverage of the same event, however, presented Duterte’s visit and comments as vindication of Russian confrontation of the US, and sought to frame the visit as the beginnings of a new “trilateral alliance” between Russia, China, and the Philippines to confront and challenge US hegemony in the Pacific region.

The data around the US presidential election, likewise, sought to demonstrate the failings of US style democracy. Both Russian and Chinese media generally portrayed the election as a farce, and evidence of clear US hypocrisy regarding democratic values. Overall, extensive media coverage undermined US prestige and “soft power” and sought to portray both Russia and China as vindicated in the court of global opinion.

This analysis, however, found significant and important differences between the overall tone of Russian and Chinese geopolitical narratives. Chinese media articulated concerns and complaints about the global order, and that China should rightfully take a greater role in global affairs. However, Chinese media sought to include China into the mainstream of the existing global order, and complain about exclusion from the current system. Russian media, however, sought to delegitimize the current world order, and to replace it with something less beholden to US and European interests. Overall, Russian media enacted a “gray zone” character much more frequently, in utilizing ambiguity, aggression, and perceived injustice to expand Russian interests against those of the Western world. Conversely, Chinese media sought much more frequently to argue for China’s full inclusion and participation in global affairs, and rarely portrayed the current global system as wholly corrupt and controlled by the US and Europe.

[Q11] What opportunities are there to leverage ally and commercial capabilities to enhance the resilience of space services for commercial and national security critical space services? What are the major hurdles to doing so? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

The importance of strengthening the resilience of US space capabilities is directly addressed in the 2010 National Space Policy, and the 2011 National Security Space Strategy. While these documents identify resilience as central to mission assurance, they do not provide any detail on what comprises resilience in the context of US space capabilities. The 2012 DoD Directive 3100.10 is consistent with these documents and offers the following definition of resilience:

- The ability of an architecture to support the functions necessary for mission success with higher probability, shorter periods of reduced capability, and across a wider range of scenarios, conditions, and threats, in spite of hostile action or adverse conditions. Resilience may leverage cross-domain or alternative government, commercial, or international capabilities.

The experts who responded to this question represent both the government and commercial space sectors, and academia and think tanks (see above Q11: Contributors figure). Overall, there was consensus among contributors that there are significant opportunities for collaboration between the USG and allies, and the USG and commercial actors. The contributors to this question identified over 70 distinct allied and/or commercial capabilities that could be leveraged to enhance resilience (see Table 1 below). To provide an overview of how these specific capabilities may contribute to US space activities, we grouped them according to the more general service (activity or purpose) that the expert discussions specified. From this analysis, eight categories of service emerged. As shown in Figure 1, information (collection and analysis) was the most frequently referenced category, followed by launch (infrastructure, vehicles, and services).

Approaches to enhancing resilience

From the contributors’ discussions of these capabilities, two general approaches to enhancing resilience, consistent with the DoD definition above, were identified: enhancing capabilities and providing redundancy.

Enhance capabilities

Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson of the United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College identifies commercial advances in space-based solar power as contributing to resilience, by enabling the powering of systems capable of earth observation from higher orbit. Solar electric propulsion, Dennis Ray Wingo of Skycorp, Inc. suggests, enables the development of spacecraft that would “simply be able to move out of the way of most ballistic threats, thus passively defeating attacks.”5 Furthermore, distance provides protection to space-based assets, as it requires greater capabilities on the part of our adversaries to disrupt them, and is harder to achieve “without revealing intent” (Wingo). It also makes such assets less vulnerable to unintentional damage or destruction from space debris.

Coming from a slightly different perspective, Wes Brown and Todd May of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center note that cooperative efforts with allies or commercial actors could help bridge capability gaps created by politically driven changes in USG budget priorities that potentially impact national security needs. They offer the recent drop in support for Earth science and remote sensing as examples of this.

Increase speed of innovation and adoption of new technology

Discussion of the faster pace of innovation in the commercial sector was also common.6 The underlying message being that leveraging commercial capabilities would bring the added advantage of providing the USG with more advanced technologies more quickly. Use of allied and commercial capabilities would also reduce reliance on the federal acquisitions cycle, which is notoriously slow and cumbersome, resulting in outdated systems and a reduction in the United States’ relative capability advantage over its adversaries (Hampson).

Improve space servicing capabilities

Contributors discussed two ways in which cooperation with commercial actors and/or allies in the provision of space servicing may enhance US capabilities. The first of these was space traffic management—knowing where things are with a greater degree of precision (Dr. Moriba Jah, University of Texas at Austin) and removing objects that are endangering that traffic (Rossettini). The second was the maintenance and upgrading of capabilities in space. In particular, a number of experts7 discussed the potential of commercial developments to increase the feasibility of on-orbit servicing of satellites. Such a capability could increase the lifespan of expensive GEO-satellites, and enable modifications and repairs.

Increase coverage

Dr. Patrick Stadter of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory sees potential for commercial actors to supplement SIGINT capabilities by providing observations and data analysis in areas that are either not covered by existing USG capabilities or in instances where specific data requirements were not predicted in time. Berkowitz suggests that interoperability with commercial and allied communication, PNT, and remote sensing systems would increase distribution (orbit, spectrum, geographically) of US capabilities. Brown and May also see allies and commercial actors as offering the potential for the USG to broaden the geographic location of its ground services to increase coverage and redundancy.

Provide redundancy/back-up

As Steve Nixon of Stratolaunch Systems Corporation points out, “we don’t stockpile anything when it comes to space. . . .War fighting always involves the possibility of living with attrition. We buy extras and we keep them in reserve to put them into conflict as needed. . . .Space is not like that.” His view that this situation needs to change if the US wants to improve its ability to deal with contested space is implicitly reflected in the responses of the other subject matter experts that responded to this question. Several contributors8 suggested that leveraging allied and/or commercial services in addition to existing USG capabilities would add resilience through proliferation (adding to the number of assets serving national security needs) or diversification (different types of assets). Doing so would introduce a level of redundancy in US space capabilities that is currently lacking (Hampson), and thus increase the speed with which the US could resume services interrupted by accidents or attack (Brown and May).

More specifically, Berkowitz suggests that “[a]llied launch infrastructure, vehicles, and services could serve as a backup to US capabilities in extremis” (see also Hampson). Wingo proposes that developing commercial capabilities may, in the future, enable the placement of communications and data storage systems on the Moon, providing back-ups that are “impervious to electromagnetic pulse damage.” The Spire Global Inc. team notes that employing commercial satellite constellations would make systems “nearly impossible to destroy,” and Hampson suggests that commercial satellites could also provide back-up information services to ensure that the US is never “blind.”

Major hurdles to leveraging allied and commercial capabilities for resilience

All of the contributors identified at least one substantial way in which allied and commercial capabilities could be leveraged to enhance the resilience of US space services.9 Almost all, however, also identified barriers (either within the USG or between the USG and allies or commercial actors) to such cooperation.

Security/reliability concerns

Once systems are connected, each is only as secure as the most vulnerable, and as Brown and May discuss, “[t]his is of particular importance when considering US allies have partnerships with our adversaries for use of similar if not the same capabilities.” Faulconer Consulting Group raises a related concern, noting that leveraging external capabilities will mean that the workforce will include a broader set of contractors and civil servants. Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson of the United States Air Force Academy questions whether concerns on the government side over classification will allow for the data sharing that collaboration with allies and commercial actors may require. Finally, a number of contributors indicated that mission assurance and control could prove a barrier (Robert D. Cabana, NASA–Kennedy Space Center; Nield), due to concerns over command and control switch over in times of need (Faulconer Consulting Group) or reliability (Hampson). Berkowitz notes that the “track record is decidedly mixed regarding the reliability of political commitments and commercial contracts in crisis and conflict.”

Attitude

Security concerns also underpin some of the contributors’ observations that the attitude of the US defense community may also prove a hurdle (Berkowitz; ViaSat, Inc.) Still more contributors suggest that the problem is cultural, including a lack of understanding of the breadth and depth of commercial and allied capabilities (Bryce Space and Technology; Wingo), or a vision of how such a partnership would look (Major General [USAF ret.] James Armor, Orbital ATK). Wingo suggests that, for the USG, “anything that is not quantifiable through the lens of past experience is considered risky, and thus downgraded in evaluation and thus unlikely to be funded”—an approach that is diametrically opposed to that of many of the new commercial space ventures. Such divergent perspectives create a significant hurdle to collaboration.

Organizational barriers

Organizational barriers both within the USG and between the USG and allied and commercial actors were also identified as a hurdle to collaboration. Deborah Westphal of Toffler Associates and Hampson both note that it is unclear which USG agency would orchestrate collaboration of this sort, and Dr. T.S. Kelso of Analytical Graphics, Inc. suggests that the procurement cycle presents another internal barrier even when there is need for and interest in an outside capability. Organizational barriers also exist between the USG and allies. Leveraging the assets of another state requires both political and legal arrangements (Berkowitz) and from the US side, there are also export control rules and classification concerns (Hampson). For commercial actors, the lack of clarity and transparency regarding USG timelines, and infrastructure and communication needs in times of conflict, present a hurdle (Stratolaunch Systems Corporation), as does the lack of clarity in policy across government agencies to support commercial activities (Cabana). Finally, just as the USG has concerns over classification, commercial actors may be unwilling to share their information due to concerns over intellectual property and competitive advantage (Jackson; Harris Corporation, LLC).

Interoperability

Even if organizational barriers are overcome, technical barriers remain, in particular the complexity involved in ensuring interoperability across a wider variety and number of service providers (Berkowitz; Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; ViaSat, Inc.). As Hampson states, “Compatibility across systems can be difficult if they are originally constructed with differing end goals in mind,” which will be the case if the USG moves to integrate commercially developed capabilities with its existing custom capabilities.

Divergent goals

Collaboration requires at some level shared goals and priorities, which is not necessarily the case when it comes to the defense and commercial space communities. Commercial actors need to be profitable, and without a good probability that there will be revenue at the end, they will be unwilling or unable to put money toward developing a capability specifically to meet a national security need, if there is no market demand (Harris Corporation, LLC; Hampson; Roesler; Wingo).

Overcoming hurdles to leveraging allied and commercial capabilities

In addition to identifying hurdles to cooperation, the contributors also discussed changes that could reduce some of these barriers.

- The US defense community needs a better understanding of and relationship with the commercial space sector (Roberto Aceti, OHB Italia S.p.A.; Armor).

- Regulatory and policy frameworks and lines of authority need to be developed (Garretson; Hampson; Kelso; ViaSat, Inc.; C. Weeden; Westphal).

- Areas specified: access and control assurance (ViaSat, Inc.), quality control (Hampson), IP and data protection (Jackson), and space traffic controls (Chwastek).

- Technical and funding support to build a strong, stable commercial sector (Brown and May; Cabana; Carol; Wingo).

Contributors

Roberto Aceti (OHB Italia S.p.A., Italy); Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Dr. Daniel N. Baker (University of Colorado—Boulder Campus); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Wes Brown and Todd May (NASA—Marshall Space Flight Center); Bryce Space and Technology; Robert D. Cabana (NASA—Kennedy Space Center); Caelus Partners, LLC; Elliot Carol3 (Ripple Aerospace, Norway); Matthew Chwastek (Orbital Insight); Dr. Damon Coletta and Lieutenant Colonel (USAF ret.) Deron Jackson (United States Air Force Academy); Faulconer Consulting Group; Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Lieutenant Colonel Peter Garretson (United States Air Force Air Command and Staff College); Joshua Hampson (Niskanen Center); Harris Corporation, LLC; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Dr. T.S. Kelso (Analytical Graphics, Inc.); Dr. George C. Nield (Federal Aviation Administration); Dr. Gordon Roesler (DARPA Tactical Technology Office); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Spire Global Inc.; Dr. Patrick Stadter (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory); Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; ViaSat, Inc.; Charity A. Weeden (Satellite Industry Association); Dr. Edythe Weeks (Webster University); Deborah Westphal (Toffler Associates); Dennis Ray Wingo (Skycorp, Inc.)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

[Q7] Are other nations outside the West poised to tap into their own commercial space industry for military purposes in the next 5-10 years?. A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

Background

All the experts who contributed to this question noted that it begins from the incorrect assumption that space industries in other countries are organized in a similar manner to the US—with clear delineations among civil, military, and commercial space industries. Furthermore, most indicate that, taking advantage of the dual use nature of much space technology, many states both non-Western and Western, are already tapping commercial and civil space capabilities for military use. Their responses suggest that a better way to frame this question might be: “Which nations outside the West are tapping into their civil (commercial and/or government run) space industry for military purposes?”

Lack of separation between public and private space sectors

Several contributors comment specifically on the organization of space sectors in countries outside the West. Marc Berkowitz of Lockheed Martin notes that while both our European and Asian allies have separate public and private space sectors, “there is a very permeable membrane between their governments and commercial industry” (see also ViaSat, Inc. and Roberto Aceti of OHB Italia SpA). Faulconer Consulting Group suggests there is no separation at all in China. Victoria Samson of the Secure World Foundation similarly observes that, although the Indian space agency ISRO has a commercial wing (Antrix) that develops a lot of their commercial capabilities, it is funded by the Indian government and not, she argues, truly commercial. Berkowitz mentions that Russia, Iran, and North Korea are comparably organized, with “commercial” space enterprises wholly owned by the government.

In effect, there are fewer institutional barriers to military use of civil (government and/or commercial) capabilities and, in many non-Western states Aceti contends, there are in fact institutional incentives for government and commercial entities to work together. Additionally, the “[c]utting edge of technology and performance is being defined by truly private sector capital investments” (ViaSat, Inc.), incentivizing militaries to tap commercial capabilities. Such arrangements also benefit commercial entities, as joint ventures provide protection by national governments (Caelus Partners, LLC). Major General (USAF ret.) Armor4 regards this as part of the development of the industry: “It’s blending in all directions, not unlike the IT industry.”

Military utilization of civil capabilities

An anonymous commercial executive contributor stated that it is a “safe assumption that other countries see the benefits of space from a military perspective and have the vision to know it will only grow in the coming decade.” This view is reflective of almost all of the other experts’ responses, although Matthew Chwastek of Orbital Insight, focusing on capability rather than intent, does offer a qualification to this. He notes that none of these states currently has the “depth of capital formation, governance, and regulatory flexibility” needed to develop civilian (government or commercial) space capabilities that could benefit the military, although this situation could change in the next decade.

How is this being done? Dual use

As Table 1 shows, there was considerable agreement amongst the experts that the crossover from civil (government and/or commercial) to military use most commonly takes advantage of the dual use nature of much space technology. As Brigadier General (USAF ret.) Thomas Gould of the Harris Corporation points out, “the same rocket engines used to boost satellites into orbit can deliver conventional or nuclear warheads” (see also: Adranos, Cheng, and Samson). Theresa Hitchens of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM) contends that, with the possible exception of Russia, most space activities outside the US are concentrated on dual use technologies and applications.5 Dr. Moriba Jah of the University of Texas at Austin agrees with her assessment, and adds that the US has been behind in this regard, something he sees as a detriment to the US.

Conclusion

The contributors’ responses to this question all either directly or indirectly challenge the assumption made in the question that other states organize and conceive of their space industry in the same three- part structure—civil, military, and commercial—that we have in the US. In some cases (Russia, Iran, North Korea, and India), this is a reflection of the separation, or lack of separation, between public and private sectors in general. In other cases, it reflects the fledgling nature of many state’s space industry, where government funding and private research and investment have been combined for greater efficiency. Furthermore, this type of collaboration is already underway. While, as the summary table shows, there is some difference of opinion among experts regarding which commercial capabilities are currently being tapped by specific countries, their responses collectively reflect Dr. Jason Held’s (SaberAstronautics) comment: “Bottom line answer is: absolutely. Defining the nature and scope of that commercial industry is the big question.”

Contributors

Roberto Aceti (OHB Italia SpA, Italy); Adranos Energetics; Brett Alexander (Blue Origin); Anonymous Commercial Executives; Major General (USAF ret.) James B. Armor, Jr.2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Brett Biddington (Biddington Research Pty Ltd, Australia); Caelus Partners, LLC; Elliot Carol3 (Ripple Aerospace, Norway); Chandah Space Technologies; Dean Cheng (Heritage Foundation); Matthew Chwastek (Orbital Insight); Faulconer Consulting Group; Adam and James Gilmour (Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia); Harris Corporation, LLC; Dr. Jason Held (Saber Astronautics); Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland); Dr. Moriba Jah (University of Texas at Austin); Dr. T.S. Kelso (Analytical Graphics Inc.); Victoria Samson (Secure World Foundation); Spire Global Inc.; Stratolaunch Systems Corporation; Charity Weeden (Satellite Industry Association); John Thornton (Astrobotic Technology); ViaSat, Inc.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

US-DiGIA: Mapping the USG Discoverable Information Terrain.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., Polansky (Pagano), S., & Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

The United States currently faces a complex and dynamic security environment. States are no longer the only critical actors in the international arena; rather, a diverse range of non-state entities also has the potential to affect US interests and security—for good or bad. Economic influence, information control and propaganda, political influence, and social discontent can be and are being utilized by state and non-state actors alike to achieve their goals, in many cases bypassing the need for direct military action. In response, the US military is challenged to accomplish more, across a greater variety of domains, while facing a constrained budget environment. There are two central implications of this: first, many of the most intractable security problems the US faces require a whole of government approach. Second, in a complex and evolving international environment characterized by new and often ambiguous threats, information itself is a critical asset.

If USSOCOM and others were able to leverage these existing extant sources of information, data and expertise (i.e. information assets) held by the USG, the cost and time savings from avoiding duplication of effort would be potentially immense. In an effort to enable this, the NSI team “mapped” the USG information terrain, cataloguing all discoverable (unclassified, published, and referenced or held online) information assets relevant to national security and foreign policy held across the non-DoD and non-ODNI USG organizations.

This effort resulted in the Directory of Discoverable US Government Information Assets (US-DiGIA), which provides a tool that enables users to search for and locate open source USG information assets, and possible points of contact for interagency collaboration. The structure of the US-DiGIA is shown in Figure 1 below.

Key Findings

The US-DiGIA Directory can also be analyzed to provide an overview of the USG discoverable information terrain. This report presents some of the key findings of our analysis of the directory. Part 2 focuses on the subset of information assets relevant to gray zone challenges. It also demonstrates how tailored coding for specific issues or security concerns can increase the utility of the US-DiGIA directory for users with specific information needs.

We organized our analysis in each part around the three foundational whole-of-government questions that guided the structure of the directory itself.

- What national security and foreign policy related information does the USG currently collect and hold?

- Who (which organizations) collects and holds that information?

- Where geographically are our information assets focused?

Part 1: US-DiGIA Directory as a whole

What National Security and Foreign Policy Related Information Does the USG Hold?

- Three DIMEFILplus categories—economic, diplomatic and governing each account for approximately 15% of the total discoverable information assets.

- Trade and security are the focuses of the majority of discoverable information assets.

- When it comes to economic aspects of national security and foreign policy, the information assets identified are US-centric and focused on trade.

- When accounting for economically focused diplomatic information assets, economic-focused information assets account for 21% of all US-DiGIA assets, whereas those focused on security account for 14%.

- While more organizations hold cyber related information than economic information, only three have a clear international focus to their cyber efforts.

- Coverage of social information assets accounts for less than 10% of all discoverable information assets. Only a minority of this focuses on topics that can be directly linked to political stability.

Who Collects and Holds that Information?

- The State Department has both the greatest quantity (501 information assets) and diversity (387 topics) of information relevant to national security and foreign policy.

- Many organizations outside the intelligence community (IC), or the group of organizations that frequently coordinate with the DoD1, were found to have information potentially relevant to national security and foreign policy.

- Although the Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, Interior, and Energy all hold fewer overall assets than other organizations, they cover a broader range of topics.

- The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has a, perhaps surprising, number of relevant information assets (99), and many of these assets relate to disease detection and tracking or emergency response.

Where Geographically is that Information Focused?

- Internationally focused discoverable information assets were more numerous than were US focused.

- Identifying which information assets cover specific CCMD AORs is in many cases not possible from the published descriptions. This creates inefficiencies when searching for country or region specific information, and it makes it harder to identify countries or regions where gray zone relevant information is lacking.

Implications

Information

Lack of information leaves us functionally blind to potential opportunities to further US interests or mitigate threats to those interests. Without reliable information, it is more likely that we may incorrectly classify an action as gray and increase the risk of either unintended escalation (by assuming an action is gray when it is not) or missing threats to our interests (by assessing an action as not gray when it is in fact gray).

The ability to identify and locate information assets across a broad range of USG organizations could reduce the need for SOCOM and others to undertake their own information collection efforts. This in turn increases the efficiency of information collection and reduces cost in both time and resources.

The current scarcity of information related to potential gray actions places the US at a disadvantage when it comes to developing indicators and warnings. These gaps highlight areas where SOCOM and others could focus their own information collection efforts to maximize efficiency and impact for analysts and planners.

Whole of Government

Appreciation of the complexity of the evolving security environment has prompted calls for a whole of government approach to national security challenges. Information exchange is a logical first step in increasing awareness of common interests and information assets across the USG, and the US- DiGIA Directory can contribute to that process.

The types of discoverable information an office with an organization holds also provide an indication of the interests and expertise within that office and thus a guide to the identification of possible points for interagency cooperation. Interagency collaboration enables the practitioners who best understand specific instruments of power to be involved in their application to specific national security (including gray zone) challenges.

Similarly, bringing diverse areas of expertise and authorities together can reduce institutional bias, and reveal underlying assumptions. This can create the potential for developing a broader and more adaptive set of strategies for responding to gray zone and other national security threats and avoiding unintended consequences.

Author | Editor: Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The EUCOM video highlights work NSI did in collaboration with the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) office and the US Department of Defense to apply NSI’s Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) methodology to examine potential drivers of conflict and convergence in Eurasia over the next 5-25 years. For access to the full ViTTa analysis, please visit: ViTTa Analysis of Eurasia in the Next 5-25 Years.

Question (R4.5): Does US foreign policy strike the right balance in supporting US interests and its role as a global power? Or, should the US consider a more isolationist approach to foreign policy? What impact could an isolationist policy have on Middle East security and stability, balance of influence by regional and world actors, and US national interests?

Author | Editor: DeGennaro, P. (TRADOC G27).

Executive Summary

US foreign policy makers struggle to find the right balance in supporting US interests particularly in the Middle East. Unbalanced policies, those focusing solely on defense while marginalizing diplomacy and development, are diminishing trust in the US and decreasing its influence—challenging US ability to maintain global stability and continue to support the security of its allies. Experts agree that the United States’ ability to use statecraft has diminished due to two long-term conflicts and continued spread of the Iraq conflict into Syria.

The Middle East is a particularly challenging area of operations for the United States. Historically, military interventions in the region have resulted in rising instability and competition between states leaving many of the weaker parties—Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Yemen, and the Palestinian territories— subject to interference from the Arab Gulf countries and Iran, terrorism, and internal conflict. It is a region that is often misunderstood by most Americans due to differences in culture, disunion, religion, and group (families, clans, tribes etc.) identities and dynamics. Additionally, the region is increasingly difficult to understand due to radical group destabilization efforts.

Our contributors agree that US interests in the Middle East are focused on the free flow of oil, safeguarding allies and partners, ensuring continued nuclear nonproliferation, and combating terrorist groups that target the US and its allies. Specific US narratives in the region focus on improving democracy and human rights; however, actions like the intervention in Iraq, the focus on regime change in countries like Libya and Syria, and the inability to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict debunk those narratives across populations.

In response to the question regarding reverting to a policy of ‘isolation,” experts feel that this is not a plausible alternative since the world is becoming more interconnected. However, this does not mean the US must continuously intervene. More precisely, the US must reevaluate how it intervenes with smarter, more comprehensive policy beyond the extensive use of the military. A US isolationist policy would likely increase instability and tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran while opening doors to their continued use of proxy sources to engage in protracted conflict ensuring that Middle East stability would become unattainable. On the other hand, those that feel US policy is contributing to marginalization of groups and support of brutal dictatorships and monarchies would most likely welcome a US exit.

Fred C. Hof, Director, Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, Atlantic Council, reminds us that the issue is not a theoretical question of ‘balance’ [or isolationism]. The issue is one of competence, with the emphasis on decision-making and communication.” I would add a well thought out comprehensive policy and strategy to improve conditions in the region giving the youth opportunities to prosper instead of fight would be beneficial. Hof also states, “The thesis of intractable ancient conflicts rooted in religion and ethnicity is as faulty in the Middle East as it was in Europe.” The US insistence that this is true and that policy must therefore focus on these issues handicaps its ability to remain influential there.

Finally, US policy has been predominantly lethal military action over the last several decades with little diplomatic effort—exacerbating, not easing, one of the worst humanitarian crisis in history as well as economic hardships and the spread of terrorism. Look no further than US aid entering the region. Essentially it is all military support—one can point to Israel, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and other Gulf countries. There is little done to balance military action with other forms of statecraft. Our experts point out the need for economic, financial, or multilateral cooperation tools in order to change the current situational environment.

Contributing Authors

Perry Cammack (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), Munqith Dagher (IIACSS), Patricia DeGennaro (TRADOC G27), Fred C. Hof (Atlantic Council), Karl Kaltenthaler (University of Akron/Case Western Reserve University), Mark N. Katz (George Mason University), Spencer B. Meredith III (National Defense University), Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins School of International Studies), Janet Breslin Smith (Crosswinds International Consulting)

Author | Editor: Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc.).

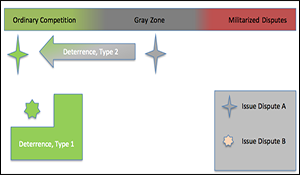

Overview

In recent years, state actors, especially but not limited to Russia and China, have increasingly engaged in what the US Government has labeled “gray zone challenges.”1 These are actions that disrupt regional stability and potentially threaten US interests, yet purposefully avoid triggering direct responses (Bragg, 2016). In earlier NSI Gray Zone Concept Papers, we argued that both malicious intent as well as violation of international norms for what is considered “ordinary competition” among states were integral aspects of gray zone challenges. This paper expands this discussion to explore what deterrence would look like in the Gray Zone, and how deterrence operates when ambiguity regarding appropriate response is added to the uncertainties that more typically characterize deterrence decisions. We argue that deterrence in the Gray Zone involves both preventing escalation to direct military conflict and assuaging an actor’s desire to violate international norms of behavior.

Foundations: Thinking through Classic Deterrence Theory

In the classic model of deterrence, a state seeking to deter should credibly threaten to impose negative consequences on a target if the same target does not comply with the action-avoidance request. Similarly, the target must be credibly assured that the deterring state will not impose harmful consequences if it refrains from taking the action.

- A state credibly threatens a target with negative consequences if the target state takes a certain action or violates a prohibition.

- The deterring state credibly assures its target that no negative consequences will follow if compliance is achieved.

- The targeted state refrains from taking the prohibited specific activities.

Academically, classic deterrence theory emerged to explain what to do about the conventional and nuclear force postures of the Soviet Union—a peer competitor that pursued a fundamentally different logic of political and economic order. The United States and the Soviet Union were in a situation of balanced power, and conceptions of deterrence derived in this setting reflected this structure.

Clearly this balanced structure no longer applies. The United States leads the world in military research and development, and enjoys one of the few long-distance power projective capabilities in the world. Moreover, the United States participates in almost every critical security institution (e.g., NATO), helped design the post-war economic institutions (e.g., GATT/WTO, IMF), and possesses military bases on every continent and near every major region of operation (Johnson, 2007; Gilpin, 2001). Our closest near competitors are states like Russia and China, which while opposed to many of the foreign policy choices of the United States and its allies, seek a larger voice in the current order, rather than a fundamentally different logic of political and economic order (Pagano, 2017).

It stands to reason that the principles of deterrence that worked best to contain the Soviet Union may differ from the principles of deterrence that work best to constrain the more limited ambitions of modern Russia and China, competitors of much lesser capability. Classic deterrence principles also seem limited in providing insight into the conditions under which we are likely to deter non-state actors (or even what deterrence of non-state actors looks like). Many approaches to countering violent non-state mobilization call for the destruction or complete dismantling of the non-state organization. Classic deterrence theory suggests that under these conditions the groups targeted would be “undeterrable,” as there is not likely the level of imposed costs that would get these group to change their behaviors.