SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Counter-Da’esh Influence Operations: Cognitive Space Narrative Simulation Insights.

Author | Editor: Linera, R. LTC, Seese, G. MAJ (USASOC) & Canna, S (NSI, Inc).

At the request of Joint Staff, the SMA program, in coordination with United States Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), participated in a second Counter-Da’esh Messaging Simulation that brought together nearly 100 Psychological Operation (PSYOP) operators, USG and international observers, interagency representatives, population experts from Iraq and North Africa, Da’esh experts, universities, and think tanks. This exercise served as both a test bed for messaging techniques and a training opportunity for PSYOP operators.

The simulation was run on a synchronous, virtual, and distributed platform called ICONSnet, designed and managed by the University of Maryland (see Chapter 6: Designing a PSYOP Wargame). ICONSnet was designed to advance participants’ understanding of complex problems and strengthen their ability to make decisions, navigate crises, think strategically, and negotiate collaboratively. This platform was selected for the following, critical reasons.

- Online, distributed platform: ran across a dozen time zones, three continents, and with over ninety participants

- Operationally relevant: provided an infrequent opportunity to test the effectiveness of USG messaging

- Regional expertise: allowed 30 regional experts to provide real-time feedback from the perspective of various population segments

- Realistic: supported the integration of audio, video, imagery, and other types of formats so that messaging came to the target audiences through the appropriate means or messengers

- Synchronous: provide live feedback that challenged USG’s operational tempo

Key Takeaways

Compared to the December 2015 Counter-Da’esh Messaging simulation, “This time the anti-ISIL side was doing it right. Volume of messaging? I know my wrist was cramping up! – Mubin Shaikh, Red (Da’esh) team member, former Salafist activist, participant in both December 2015 and April 2016 simulations.

This was a simulated environment, but preliminary results suggested lessons not only for PSYOP training but also for increasing the impact of messaging in forward operations. These results are described below.

The pre-simulation preparation and consequent volume of messaging that the Blue team was able to deploy during the April 2016 simulation appeared to confound Da’esh team efforts to deliver its own messaging and forced it into a reactive position vis-à-vis interacting with the White teams. What emerged from this simulation was the realization that an increased operational tempo within the narrative space, combined with embedded, virtual expertise from a cadre of multidisciplinary experts, appeared to increase the effectiveness3 of DoD messaging in the simulated narrative space.

Several insights from the simulation suggest means of enhancing PSYOP training and message formation:

- Develop a high level strategy that aligns with operation objectives, which is flexible enough to allow PSYOP operators agility to maneuver in the narrative space

- Set clear objectives for narrative campaigns conducted in support of overall strategy

- In advance of a narrative campaign, prepare a reservoir of tested, well developed messaging aimed specifically at target populations

- Develop messages in coordination with cultural and technical experts to take advantage of multidisciplinary insights from the fields of neuroscience, political science, modeling, and marketing, etc.

- Identify strategies for responding in real time to messaging that may be particularly effective or ineffective

- Test the effectiveness of messaging and continually refine the PSYOP training process in safe, simulated environments before fielding when possible

Degrading Da’esh Message Effectiveness

Several generalizations emerged from the simulation regarding the effectiveness of various kinds of messaging between the USG, Da’esh, and population teams.4 In an environment devoid of trust, the population teams often rejected USG messaging as lacking a credible voice. They suggested that USG messaging would only been seen as credible is if it were reinforced through action by Coalition forces. Instead, they preferred to hear counter-Da’esh messaging from local religious and cultural leaders. A surprising number of population segments were open to USG’s counter-Da’esh messaging in principle, but wanted to engage in a deeper conversation about how to effect change.

This exercise illustrated the benefit of using virtual, simulation platforms for testing not only message effectiveness, but also PO training and operational effectiveness.

Contributing Authors

Moore, C. (Joint Staff), Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI), Canna, S. (NSI), DeGennaro, P. (TRADOC G-27), Ellis, D. (University of Maryland, ICONS), Hare G. (Fielding Graduate University), Harrigan, G. (Department of Homeland Security), Hogg, J. (Fielding Graduate University), Jonas, A (TRADOC G-27), Koelle, D. (Charles River Analytics), Krakar, J. (TRADOC G-27), Liette, A. (USASOC), Ligon, G. (University of Nebraska, Omaha), Linera, R. (USASOC), Mallory, A. (Iowa State University), Martin, M. (USASOC), Mereish, K. (DHS), Morin, C. (Fielding Graduate University), Reiley, P. (SOCOM), Rutledge, P. (Fielding Graduate University), Seese, G. (USASOC), Szmania, S. (Department of Homeland Security), Taylor, P. (USASOC), Wilkenfeld, J. (University of Maryland, ICONS), Wurzman, R. (University of Pennsylvania)

Question (QL1): What are the factors that could potentially cause behavior changes in Pakistan and how can the US and coalition countries influence those factors?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

The experts who contributed to this Quick Look agree on an essential point: Pakistan’s beliefs regarding the threat posed by India are so well-entrenched that they not only serve as the foundation for Pakistan’s foreign policy and security behavior, but represent a substantial barrier to changing it behavior. Christine Fair a Pakistan scholar from Georgetown University is specific as to the target of any influence efforts – difficult as they may be: “the object of influence is not ‘Pakistan;’ rather the Pakistan army’ and so security behavior change if possible requires change in the Army’s cost-benefit calculus. The essential components of Pakistan’s security beliefs are first that India is an existential threat to the state; and second that Pakistan is at a tremendous military and economic disadvantage to its stronger neighbor. Tom Lynch of the National Defense University adds a third: Pakistan’s national self-identity as an ‘oppositional state, created to counter India.’ The nature of behavior change is relative and can occur in (at least) two directions: one aligning with the observer’s interests (for the sake of brevity referred to here as ‘positive change’), and one in conflict with those interests (‘negative change’). Encouraging positive change in Pakistani security behavior was seen by each of the experts as an extremely difficult challenge, and one that would likely require dramatic change in Pakistan’s current internal and external security conditions. The experts also generally agreed that negative change in Pakistani behavior is easily generated with no need for dramatic changes in circumstance.

Negative Change: Easy to Do

According to long-time Pakistan scholar and Atlantic Council Distinguished Fellow Shuja Nawaz, Pakistan’s current state is to “to view its regional interests and strategies at a variance from the views of the US and its coalition partners.” Moreover, Pakistan’s willingness to cooperate with US/Western regional objectives can deteriorate rapidly if the Pakistani security establishment believes those states have dismissed as invalid, or take actions that exacerbate their concerns. Specifically, actions that reinforce the perceived threat from India (e.g., Indian military build-up, interest in Afghanistan) or Pakistan’s inferior position relative to India (e.g., US strengthening military and economic ties with India; Indian economic growth) stimulate negative change. Importantly, because the starting point is already “negative” relative to US interests, these changes can take the form of incremental deterioration in relations, rather than obvious and dramatic shifts in behavior. Examples may include increased emphasis on components of Pakistan’s existing nuclear weapons program, amplified use of proxy forces already in Afghanistan, or improved economic relations with Russia.

Levers Encouraging Positive Change: A difficult Challenge

While the experts agreed that Pakistan’s deep-rooted, security-related anxieties inhibit changes in behavior toward greater alignment with coalition objectives; they clearly diverge on what, if anything might be done to encourage positive change. Two schools of thought emerged: what we might (cheekily) refer to as a “been there” perspective; and a longer- term, cumulative influence view.

“Been there” School of Thought

Tom Lynch (NDU) argues that the security perceptions of Pakistan’s critical military- intelligence leaders have been robustly resistant to both pol-mil and economic incentives for change2 as well as to more punitive measures (e.g., sanctions, embargos, international isolation) taken to influence Pakistan’s security choices over the course of six decades. Neither approach fundamentally altered security perceptions. Worse yet, punitive efforts not only failed to elicit positive change in Pakistan’s security framework but ended up reducing US influence by motivating Pakistan to strengthen relations with China, North Korea and Iran. As a consequence of past failure of both carrot and stick approaches, both Lynch and Christine Fair (Georgetown) argue that motivating change in Pakistani security behavior requires “a coercive campaign” to up the costs to Pakistan of its proxy militant strategy (e.g., in Afghanistan by striking proxy group leaders; targeted cross-border operations)3. Moreover, Lynch feels that positive behavior change ultimately requires a new leadership. Raising the costs would set “the conditions for the rise of a fundamentally new national leadership in Pakistan” and be the first step in inducing positive behavior change. Lynch believes these costs can be raised while at the same time US engagement continues with Pakistan – in a transactional way with Pakistan’s military-intelligence leadership and in a more open way through civilian engagement and connective projects with the people of Pakistan. However, Christine Fair points to US domestic challenges that mitigate against the success of even these efforts given what she argues is a lack of political will “in key parts of the US government which continue to nurse the fantasy that Pakistan may be more cooperative with the right mix of allurements.”

Cumulative Influence School of Thought

Other contributors however believe are not ready to abandon the possibility of incentivizing positive change in Pakistan’s foreign policy and security behavior. They argue that there are still actions that the US and coalition countries could take to reduce Pakistani security concerns and encourage positive change. Admittedly, the suggested measures are not as direct as those suggested by abeen there, done that approach and assume a significantly broader time horizon:

- Do not by-pass civilian authority. Equalize the balance of US exchanges with Pakistani military and civilian leaders rather than depending largely on military-to-military contact. Governing authority and legitimacy remain divided in Pakistan, and while dealing directly with the military may be expedient, analysis shows that by-passing civilian leadership and continuing to the treat the military as a political actor inhibits development of civilian governing legitimacy, strengthens the relative political weight of the military, and will in the longer term foster internal instability in Pakistan and stymie development of the civil security, political and economic institutions necessary for building a stronger, less threatened state.4 In this case the short-term quiet that the military can enforce, is off-set by increased instability down the road.

- Reduce the threat. A direct means of reducing the threat perceptions that drive Pakistani actions unfavorable to coalition interests is to actually alter the threat environment. One option suggested for doing this is to use US and ally influence in India to encourage that country to redirect some of the forces aimed at Pakistan. A second option is to develop a long-term Pakistan strategy (“not see it as a spin-off or subset of our Afghanistan or India strategies”) was seen as a way to signal the importance to the US of an enduring the US-Pakistan relationship.

- Remember that allies got game. Invite allies to use their own influence in Pakistan rather than taking the lead on pushing for change in Pakistan’s behavior. According to Shuja Nawaz, “…the Pakistanis listen on some issues more to the British and the Germans and Turks. The NATO office in Islamabad populated by the Turks has been one of the best-kept secrets in Pakistan!”

- Enlist Pakistan’s diplomatic assistance. Finally, Raffaello Pantucci of the Royal United Services Institute (UK) suggests enlisting Pakistan to serve as an important conduit in the dispute that could most rapidly ignite region-wide warfare: that between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Pakistan has sectarian-based ties with Saudi Arabia as well as significant commercial ties with Iran. Although as MAJ Shane Aguero points out increased Saudi-Iranian hostilities could put Pakistan in an awkward position, Pantucci believes that the US and allies could leverage these relations to open an additional line of communications between the rivals. Importantly, doing so would also important signal US recognition of Pakistan’s critical role in the region, which would enhance “Pakistani sense of prestige which may in turn produce benefits on broader US and allied concerns in the country.”

Contributing Authors

Nawaz, S. (Atlantic Council South Asia Center), Abbas, A. (National Defense University), Lynch, T. (Institute of National Strategic Studies – National Defense University),

Aguero, S. (US Army), Venturelli, S. (American University), Pantucci, R. (Royal United Services Institute), Fair, C. (Georgetown University)

Finland, After ‘hybrid warfare’, what next? – Understanding and responding to contemporary Russia.

Author | Editor: Bettina Renz ja Hanna Smith (Office of the Prime Minister of Finland).

More than two years after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the West continues coming to terms with the implications of this event. As discussed by the project’s the first report, the concept of ‘hybrid warfare’ quickly established itself, because it seemed to be particularly useful to explain recent changes in Russian defence and foreign policy. The report highlighted that the concept was indeed valuable in drawing the attention of policymakers to some new security challenges. At the same time, the report cautioned that beyond this initial usefulness, the concept of ‘hybrid warfare’ as an explanation for almost every Russian policy move is likely to do more harm than good to our understanding of developments in Russia, as well as to the process of identifying and implementing realistic responses.

The central purpose of the second report is to emphasise that there is no simple answer or concept, such as ‘hybrid warfare’, that can evaluate developments in Russia in all their complexity. In order to gain a nuanced understanding of changes in Russian foreign, security and defence policies differentiated questions should be asked about strengths and limitations of Russian military capabilities, developments in Russian thinking on the use of armed force, Russian foreign policy goals and intentions and possible responses to Russia, all of which need to be tailored to the concerns and requirements of specific actors and states. Such an approach enables a detailed understanding of what is really new as opposed to what merely appears to be new in accordance with the ‘hybrid warfare’ idea. Towards this end, members of the project’s panel of experts provided detailed studies on the difficulties relating to the manipulation of morel forces in war (‘information warfare’); Russia’s international image projection; changes in the use of Russian military force and conventional military power as a foreign policy tool; improvements in Russian capabilities to coordinate complex, 21st century military operations; long-term implications of inefficiencies in Russian military spending; the relevance of coercion and deterrence for understanding recent Russian military action; and international lessons in civil-military relations and their particular relevance for Finland.

The report concludes with the following recommendations:

- Russian politics is more complex than macro-level concepts, such as ‘hybrid warfare’ suggest. Responses to recent changes in Russian foreign and defence policy need to bear this in mind.

- Strong Russian area studies should be supported. In-depth understanding of Russia requires wide-ranging expertise of the country’s politics, history, culture, society and economy.

- Context is key for understanding contemporary Russia. The recent focus on ‘hybrid warfare’ has overstated the newness and uniqueness of recent Russian actions, both militarily and in terms of foreign policy. This has come at the expense of historical and comparative context, which has tended to overstate the ‘uniqueness’ of the Russian case.

- Unnecessarily overstating Russian strengths and Western weaknesses can have unintended consequences. Western countries, Finland included, should stress their own strengths first and foremost.

- While making a strategy to deal with long term challenges coming from Russia, an important factor is openness and inclusion – a key strength of liberal democracies, such as Finland.

- Bilateral relations with Russia are always also a part of larger context – it is important not only to understand Russia, but also the perceptions of other actors, states and regions on contemporary security and Russia.

Question (V1): What is Missing from Counter Messaging in the Information Domain. What are USCENTCOM and the global counter-ISIL coalition missing from countermessaging efforts in the information domain?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

“Western countries have failed to match the coordination, intensity, not to mention zealotry of the communication effort of [Daesh’s] global, decentralized movement.” Peter Welby, Centre on Religion & Geopolitics. One way for evaluating CENTCOM and the global counter-ISIL Coalition messaging is to break the idea into its three component parts: the content, the medium (the way the message is transmitted), and the messenger (see Beutel).

Content

To be most effective, messaging need to be targeted to specific populations, politically/ethnically correct, and entertaining. First, while there is a need for transnational messages (often those that seek to introduce alternative narratives—a mass targeting technique that uses non-linear messaging to achieve desired outcomes [see Beutel and Ruston]), messaging is most effective when it is tailored to local circumstances; presented by trusted, local voices; and in a format preferred by the target audience (radio, television, social media, religious services, etc.). This requires that information operators clearly understand the motivations, interests, and world views of potential adherents (Zalman). Based on analysis of extremist narratives by Scott Ruston at Arizona State University, an effective system of alternative narratives must recognize the need for justice, recognize threats faced by the target audience, must offer some route to glory (resolution), and must offer some subjection to a higher ideal (whether that is family, tribe, or nation). Nuanced understanding of the target audience can serve to not only contextualize the type of messaging effort and its aims but also to provide a necessary constraint upon the expected return of these programs (Huckabey & Picucci).

Related to this, because existing rivalries, ethnic differences, and stereotypes are so difficult to unravel in MENA, extra caution should be employed not to inflame tensions during conditions requiring a fast response (Briant). Unsuccessful counter-sectarian messaging could exacerbate or entrench divisions. Erring on the side of caution is better than attempting and failing counter- sectarian messaging.

Third, compared to ISIL messaging, Coalition messaging is frankly boring (Bean & Edgar, Taylor, Welby). MAJ Patrick Taylor, 7th Military Information Support Battalion USASOC, noted that “to entertain is to inform and to inform is to influence.” Yet, Coalition messaging lacks humor and is sonically sterile. ISIL frequently utilizes music and sound (often via nasheeds) to strengthen and complement its written or spoken message (Bean & Edgar). Aside from incorporating music and sound into Coalition messaging, satire and humor may be used to expose ISIL’s failings, inconsistencies, and false claims (Taylor).

Medium

Effective messaging conveys targeted messages to local communities via preferred channels (Beutel). This could be via radio, television, trusted religious leaders, etc. Social media is not the only or best way to reach all audiences. Therefore, information operators need to develop “multiple access points” so that populations have various way to access and interact with the message in familiar formats (Taylor).

Messenger

Experts largely agreed that a significant obstacle facing Coalition messaging efforts is that it lacks credibility. Government entities are not credible voices (Beutel). While there is a significant cohort (Abbas, Braddock, and Ingram) that argues in support of better leveraging and supporting local, credible partners to disseminate messages, there is another cohort (Briant, Beutel, Everington) that believes that credible voices have to be free of any kind of government support, which threatens to taint the source if discovered. But one thing the USG can credibly do is to amplify the voices of defectors and refugees from ISIL-held areas to call attention to ISIL’s failure to live up to its promises (Elson et al).

Strategies for Filling in the Gaps in Coalition Messaging

A team of experts from George Mason University, led by Dr. Sara Cobb, argued that engagement, rather than countermessaging, is the most effective shaping tool. Efforts to transform existing narratives through engagement would satisfy the same objectives often achieved through traditional messaging while still “disrupting” adversary conflict narratives and shaping conditions conducive to later stability and/or peace operations.

Similarly, Alexis Everington, who has conducted primary research in Syria, noted that we are in a post-messaging phase in the region where “messages are no longer useful and their potential ran out several years ago.” Efforts should now be focused on narrowing the “say/do” gap (Beutel, Briant, Everington, Mallory). Beutel and Mallory argue for a narrative led operation that closely ties US messaging to the operational action plan.

As the Coalition narrows its say/do gap, it should work to create a wedge between ISIL and its target audience by highlighting ISIL hypocrisies and failures (such as violence against Sunnis, failure to provide services, or evidence of corruption of its leaders) (Ingram, Elson et al). It is important also to respond quickly to contradict disinformation (Beutel). Another effective strategy would be to prepare messaging ahead of time for anticipated events in order to be able to disseminate quality messaging as events unfold in real time (Mallory, Ingram).

In terms of enhancing effectiveness of current messaging, recognition of how red understands the goal and vulnerabilities of its own messaging efforts can provide improved guidance on where counter-messaging can be effective and where non-response may be a more productive approach (Huckabey & Picucci). Furthermore, the authors suggest that implanting a graduated process toward achieving desired end-states can be leveraged to provide a stronger linkage between measures of performance and measures of effectiveness.

Finally, Alejandro Beutel, a researcher at the University of Maryland’s START center, believes that one of the best things the USG can do is to play the role of “convener.” While CENTCOM may not be credible to the target populations, CENTCOM is at least credible to the credible messengers. So what CENTCOM might be able to do is to play the role of convener to have gatherings where actors in the region can interact with one another and start to establish some mediums of communication and relationship building.

Contributing Authors

Abbas, H. (National Defense University), Bean, H. (University of Colorado Denver), Edgar, A. (University of Memphis), Beutel, A. (University of Maryland, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism), Blakely Jr., C. (George Mason University), Bornmann, J. (MITRE), Braddock, K. (Penn State University), Briant, E. (George Washington University), Cobb, S. (George Mason University), Elson, S. (MITRE), Everington, A. (Madison Springfield Inc.), Geitz, S. (MITRE), Grenlin, E. (George Mason University),Huckabey, J. (Institute for Defense Analysis), Ingram, H. (Australian National University), Kuznar, L. (NSI), Lewis, M. (George Mason University), Mallory, A. (Iowa State University), Martinez, A. (George Mason University), Maye, D. (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University), Parks, M. (MITRE), Picucci, P. (Institute for Defense Analysis), Ruston, S. (Arizona State University), Shaikh, M. (University of Liverpool), Spitaletta, J. (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory), Taylor, P., (USASOC), Welby, P. (Centre on Religion and Geopolitics), Zalman, A. (Strategic Narrative Institute)

Question (R3 #1): Are Government of Iraq initiatives for political reconciliation between the sectarian divide moving in step with military progress against Da’esh, and what conditions need to be met in order to accommodate the needs of the Sunni population?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Winning the War, but Losing the Peace

“With every step of the military operation, the gap is widening between Shia and Sunnis.” – Scott Atran, ARTIS

The general consensus among contributors to this essay is that not only is political reconciliation lagging behind military progress, but that the gap is widening every day (Atran, Dagher & Kaltenthaler, Hamasaeed, Mansour). The government is not focused on reconciliation, it is focused on the anti-ISIL fight, budgetary issues, and Shia in-fighting (Slim). Furthermore, among the Shia population, there is a general sense that Sunnis lost twice already and that there is little need for reconciliation with them (Slim).

So why are national reconciliation efforts failing? It is not due to lack of initiatives; in fact, there are so many that they are perceived to be more like pronouncements rather than planned, meaningful efforts (Abouaoun, Al-Qarawee, Ford, Wahab). Furthermore, many of these initiatives are being led by international organizations (Liebl). Lack of meaningful national reconciliation efforts have convinced some Sunni Arabs that the Iraqi government intends to revert to the political status-quo ante after ISIS is defeated militarily (Dagher & Kaltenthaler).

The “Historical Settlement” initiative announced at the end of October seemed to hold promise of a post-ISIS reconciliation until parliament passed a law in November legalizing and recognizing Shia Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), which Sunnis find an abhorrent form of government- sanctioned sectarian violence (Atran, Hamasaeed). Other unhelpful actions have included the failure to pass the National Guard Law and stripping the amnesty law of important content, according to Hamasaeed. Because of this, other GoI “initiatives” have largely been perceived as lip service to vague promises of reconciliation. These kinds of efforts will not address Sunni Arab or Kurdish grievances (Abouaoun).

One expert pointed out that reconciliation cannot just take place at the national level, it must also occur locally (Hamasaeed). Local efforts will be needed to remediate revenge violence among tribes as well as prepare for the return of over three million displaced people that could undermine military gains (Hamasaeed, Natali, Yahya). “Tribal and other forms of local violence could become a game changer” and should not be ignored, according to Hamasaeed.

However, other experts noted—without discounting the daunting challenges of reconciliation—that there are a few positive signs. First, there is a group of advisors around Prime Minister Abadi who believe that a new compact must be struck with the Sunnis, but this group is not powerful enough to effect change by itself (Slim). Second, two experts noted that in speaking with people on the ground that there is a general sense that reconciliation efforts have proceeded better than expected (Natali, Serwer). Third, in general, Sunni Arabs continue to largely see themselves as Iraqi nationalists and are committed to Iraq’s territorial integrity (Natali). Finally, while Sunnis are completely opposed to the presence of Iranian-backed PMFs in their communities, many expressed a willingness to cooperate with Iraqi Security Forces (Natali).

Experts mentioned five underlying barriers to effective reconciliation.

- PM Abadi lacks the support of his Shia alliance, which he has not been able to secure due to intra- Shia rivalries (Abouaoun, Al-Qarawee, Ford, Liebl, Natali, Serwer). It is not clear that Shia hardliners will ever agree to reconcile or share power with the Sunni population (Hamasaeed).

- Intra-Sunni competition means that Sunnis are not united behind a single, clear agenda and likely will not be until free elections can be held (Al-Qarawee, Al-Shahery, Liebl, Maye, Natali, Wahab, Serwer).

- Regional powers are taking advantage of the power vacuum to promote their own agendas under the guise of protecting the Sunni population (Al-Qarawee).

- Budget: Iraq has an 18 billion dollar budge deficit (Yahya). Iraq’s huge financial outlay combined with an inadequate inflow of funds means the Iraqi government cannot afford reconciliation initiatives (Liebl).

Conditions for Reconciliation

Sunnis do not speak with a single voice and do not have a unitary agenda, but the list below comprises some of the most frequently mentioned grievances. Experts noted that these grievances are not sectarian in nature—like most populations, they desire elements of basic good governance: security, justice, jobs, and equality under the law (Natali, Liebl). Furthermore, the Sunni population has to feel that they have a secure, just, and prosperous future in the country (Dagher & Kaltenthaler, McCauley, Natali, Serwer). The failure to deliver these demands may lead to further instability and unrest.

The list below touches on the most frequently noted demands from the Sunni population. For more detail, please refer to the cited contributions.

- Security. Perhaps the most frequently mentioned issue is security (Serwer, Van Den Toorn). This encompasses many elements: freedom from tribal-based revenge and retribution for offenses committed during ISIS’s rule (Serwer, Van Den Toorn) and removal and disempowerment of Iranian-backed militias, which Sunnis consider to be a bigger threat than ISIS (Abouaoun, Al- Shahery, Atran, Liebl, Nader, Natali, Yahya).

- Justice. Reconciliation efforts must address forms of structural discrimination against Sunnis (Al- Shahery, Meredith). This broad category emphases many complaints: 1) need to moderate retributive justice (Meredith), 2) national policies that discriminate against Sunnis in government and military positions (Al-Shahery), 3) due process for those accused of supporting ISIS (Al- Shahery, Slim, Yahya), equal treatment under the law (Natali, Yahya), and 4) insistence on public accountability for those guilty of government abuses and corruption (Ford).

- Self Determination. Local reconciliation efforts are just as important as national ones (Hamasaeed). Sunnis want more control over their lives (Maye, Wahab). Sunnis desire the authority to control their own territory and resources, determine local power sharing arrangements, provide security through local police force, hire for local government positions, and have meaningful participation in decision-making (Al-Shahery, Hamasaeed, Ford, Maye, McCauley, Natali, Serwer, Van Den Toorn)

- Humanitarian Assistance. Experts agreed that humanitarian assistance must be an immediate priority following the liberation of ISIS-controlled territory (Al-Shahery, McCauley, Natali, Slim). Assistance will be needed far beyond what has already been promised by the international community.

- Reconstruction Aid. It is clear that areas liberated from ISIS control will need massive and immediate reconstruction aid; however, there is deep skepticism about the political will to provide this assistance (Al-Shahery, Ford, Maye, Serwer, Yahya). There was a plan to rebuild Fallujah, but no progress has been seen on the ground yet (Al-Shahery, Natali).

The failure of the GoI to seriously address the grievances of the Sunni community could lead to a three- fold threat of destabilizing outcomes: a power vacuum where regional powers and their proxies escalate the fight (Mansour); a failed state where warlords, extremist groups, and transnational criminals thrive (Buddhika, Petit, Reno); or the rise of a ISIS 2.0 (Dagher & Kaltenthaler, Natali, Yahya). Hamasaeed underscored the severity of the political climate in Iraq by stating that “today Iraq has more ingredients for violence than before Da’esh took over one-third of the country.”

What Can Coalition Partners Do?

Contributors outlined a few actions that the US government and its coalition partners could do to facilitation reconciliation.

- Do not approach reconciliation through an ethno-sectarian lens—it not only ignores complex political realities on the ground, but it threatens to reverse important political and societal shifts that have happened in the last two years (Natali).

- Demonstrate genuine and firm support for PM Abadi if he adopts an effective and detailed plan for re-integrating Sunni communities. If he fails to do so, threaten the withdrawal of this support. However, this must be communicated in a way that recognizes the pressure he is facing from Shia hardliners (Al-Qarawee).

- The USG and its partners can allow Sunni areas the protected breathing space to reorganization themselves and hold election of new, local leaders (Dagher & Kaltenthaler, Meredith, Serwer). This also includes acting as a neutral intermediary to bring together international, regional, national, and local leaders to facilitation communication and reconciliation (Hamasaeed, Meredith, Van Den Toorn).

- Reinforce Iraqi state capabilities and sovereignty by preventing regional powers from impeding the stable future of Mosul and other Sunni-majority areas (Dagher & Kaltenthaler, Natali).

Conclusion

Contributors noted that reconciliation efforts need to begin now while there is still military cooperation against a common enemy (Mansour, Yahya). As ISIS is defeated, local and regional actors may devolve into violence if a political vacuum emerges. One danger is that if legitimate Sunni grievances are not acknowledged and addressed, the emotions that gave rise to nationalism may once again become a powerful source of political mobilization in Iraq (McCauley). The intractable nature of the challenges listed in this essay led at least one contributor to conclude that there is little-to-no chance for reconciliation in Iraq at this time (Liebl). We may be in a situation where many of the actors’ interests are better served by continued conflict than resolution (Liebl, Astorino-Courtois).

Contributing Authors

Abouaoun, E. (United States Institute of Peace), Al-Qarawee, H. (Brandeis University), Al-Shahery, O. (Atkis Strategy), Atran, S. (ARTIS), Dagher, A. (IIACSS), Ford, R. (Middle East Institute), Hamasaeed, S. (United States Institute of Peace), Jayamaha, B. (Northwestern University), Kaltenthaler, K. (University of Akron), Liebl, V. (Center for Advance Operational Cultural Learning), Mansour, R. (Chatham House), Maye, D. (Embry Riddle University), McCauley, C. (Bryn Mawr College), Meredith, S. (National Defense University), Nader, A. (RAND), Natali, D. (National Defense University), Petit, K. (George Washington University), Reno, W. (Northwestern University), Serwer, D. (Johns Hopkins University), Slim, R. (Middle East Institute), Van Den Toorn, C. (American University of Iraq Sulaimani), Wahab, B. (Washington Institute), Yahya, M. (Carnegie Endowment)

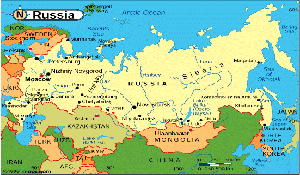

Geopolitical Visions in Russian Media.

Author | Editor: Hinck, R. et al. Hinck, R. (Texas A&M University).

This study sought to examine future political, security, societal and economic trends to identify where U.S. interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests, and in particular, identify leverage points when dealing with Russia in a global context.

USEUCOM requested that the SMA team initiate an effort to provide the Command analytical capability to identify emerging Russian threats and opportunities in Eurasia. The study sought to examine future political, security, societal and economic trends to identify where U.S. interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests, and in particular, identify leverage points when dealing with Russia in a “global context.” In order to provide insight into these questions, this report conducted a cross-platform media analysis of Russian language media to discover emerging geopolitical threats and opportunities. This joint study was completed by researchers at Texas A&M University, University of Alabama, and Mississippi State University using the Multi-media Monitoring System (M3S) at Texas A&M University.

Media, in numerous formats, has an inordinately large role in shaping and conditioning public opinion, as well as in social organization and mobilization. Recent media in Russia reflects a deterioration of relations with the West, and seems to be contributing to a general distrust of the West among Russian citizens. This distrust is not just expressed in international politics, but in the everyday lives of many Russian citizens, leading to a palpable change in their relations with Westerners. This study sought to investigate the contours of the Russian geopolitical worldview by a close analysis of a diverse array of media sources, to determine the key narratives driving perceptions of Russia’s current economic status, its role in geopolitical relations, and its rivalry with the West.

In order to better understand the dynamics of foreign policy decision-making by the leadership of Russia, this study analyzed Russian language media (broadcast and web) to understand key frames and cultural scripts that are likely to shape potential Russian political beliefs and attitudes. Three separate studies were conducted. The first focused on Russian media coverage of economic issues. The second examined Russian multilateral engagement. The third looked at Russian media portrayals of NATO. The studies covered several months of media reports from web-based news sites, journals, and commentary, as well as broadcasts from the state-owned broadcaster Rossiya 24. Altogether, the researchers monitored over 2,500 news items from fourteen different news sources.

Key Findings:

- Russian media narratives provide a glimpse into the contours of an emerging geopolitical worldview in Russia that could dramatically impact the international order.

- Overall, this worldview positions Russia as a rational and moderate geopolitical actor, standing against the corruption and recklessness of the “Euro-Atlantic” world; namely, the United States and the European Union.

- Russian policy is committed to deflecting the economic impact of Western isolation on the Russian economy.

- Russia is committed to the development of alternatives to global political and economic institutions that are dominated by the United States and the EU. Such alternatives include increased economic ties with China and other Central Asian nations, the Eurasian Economic Union, and the BRICS nations. Russia is actively attempting to cast doubt on the credibility and integrity of Western- dominated institutions.

- hiRussian propaganda comments, refutes, and covers an expansive range of issues, tracking U.S. policy, NATO and exploits dissension within U.S., EU, and NATO ranks, leaving the United States at a communication disadvantage.

Implications & Recommendations

- Although Russian media typically portrays the West as seeking to constrain Russian interests (as well as the interests of other developing nations), there are gaps within those narratives that provide openings for more meaningful engagement. Potential weaknesses within these narratives include the over- dependence on resource-based economics, discomfort among Russia’s neighbors over Russian actions, and comparisons of contemporary Russian life with narratives of political openness.

- Blanket condemnation of Russian policy and Vladimir Putin are likely to fail, as they are interpreted primarily as indicative of an indiscriminate anti-Russia doctrine. U.S. messaging that seeks to strengthen groups within Russia that are seen as anti-Putin are unlikely.

- Within the Russian Federation itself, given the centralization of political discourse in Russian media, messages that merely critique or dismiss Russian messages are unlikely to break through dominant narratives anchored in historical and cultural experiences. Developing transcendent narratives that both acknowledge Russian concerns and perceptions but build upon common interests and aspirations are likely to have a greater impact than narratives that seek to isolate Putin from the Russian populace.

- Audiences exterior to the Russian Federation are more likely to be receptive to messages that highlight incoherence or lack of fidelity within Russian geopolitical narratives.

- Without clearly stated goals, U.S. involvement in countries surrounding Russia’s borders allows for Russia to present U.S./NATO activity as a threat to their own national interests.

Contributing Authors

Cooley, S. (Mississippi State University), Hinck, R. (Texas A&M University), Kluver, R. (Texas A&M University), Manly, J. (Texas A&M University), Stokes, E. (University of Alabama)

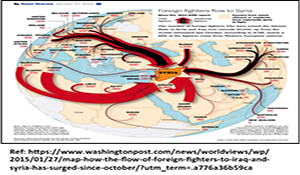

Question (LR3): What actions and polices can regional and coalition nations employ to reduce recruitment of ISIL inspired fighters?

Author | Editor: Cragin, K. (National Defense University).

This paper addresses the issue of ISIL recruitment from Literature Review Question #3. To do this, it utilizes a quick look format and focuses on two non-standard ideas approaches to challenge of terrorist recruitment. For readers interested in source materials on this subject, this paper also incorporates a bibliography at the end of the document.

Minimize the impact of existing foreign fighters and returnees

The single most significant policy that nations could employ to reduce recruitment of ISIL fighters in the future is to minimize the influence of returnees. Historically, most foreign fighters have returned home from conflicts overseas to recruit and build local networks. Take, for example, the case of Afghanistan in the 1980s and 1990s. Approximately 80 per cent of the 20,000 foreign fighters returned home and recidivism rates ranged from 40 per cent (Indonesia) to 90 per cent (Algeria). Moreover, even in the case of Indonesia, which had the lowest rate of recidivism, returnees recruited and expanded local terrorist networks. In fact, recent interviews in Indonesia with Afghan veterans revealed that foreign fighters were instructed to recruit 10 new operatives each, once they got home.

Emphasize programs that reinforce non-radicalization

Another policy that nations could employ to reduce recruitment of ISIL fighters in the future is to implement programs that reinforce non-radicalization. Generally speaking, radicalization can be understood as a process whereby individuals are persuaded that violent activity is justified in pursuit of some political aim, and then they decide to become involved in that violence. However, many of the factors that push or pull individuals toward radicalization are in dispute within the expert community. Much of the problem is that the factors identified by experts as contributing to radicalization apply to many more people than those who eventually become involved in political violence. Such limitations are more than academic, because they make it difficult for policymakers to design interventions. These limitations lead to programs aimed at manipulating broad structural actors—for example, education—so that they affect small subsets of populations of people who might or might not decide to become terrorists. One alternative is to instead focus policies on encouraging individuals to reject violent extremism.

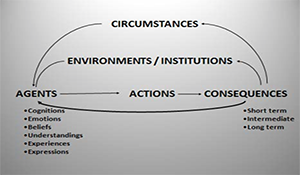

Assessing and Anticipating Threats to US Security Interests: A Bio-Psycho-Social Science Approach for Understanding the Emergence of and Mitigating Violence and Terrorism.

Author | Editor: Giordano, J. (Georgetown University Medical Center).

This white paper represents the work of intra- and extramural subject matter experts (SMEs) from multiple disciplines, convened to provide views and insights to define and further develop a bio- psychosocial approach to understanding, assessing, and influencing the cognitions and behaviors of individuals and groups that are devising, recruiting, training, and implementing organized aggression and violence. In light of current national and international security concerns, a major focus of this report is upon those bio-psychosocial factors that are influential to, and influenced by the activities of the group known as Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant— ISIL (or Daesh/Da’ish).

Over the past four years, ongoing activities of the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) group have focused upon the validity and viability of neuro-cognitive techniques and technologies to be operationalized within national security, intelligence, and defense initiatives. Operationally, neuro-cognitive approaches have been, and are being evaluated, and in some cases iteratively employed, in the assessment, analysis, interdiction, influence, mitigation, and/or deterrence of factors contributory to intent and acts of global aggression and violence that threaten the United States (US) and its allies.

Through these projects, it was recognized that the value of neuro-cognitive techniques and technologies are best—and in some cases only—realized if and when they are incorporated and employed within (and to optimize) a more expansive orientation to human thought and action, which encompasses, appreciates, acknowledges, and engages the interactive dynamics of humans-in-environments.

This approach is known as the bio-psychosocial model, with homage to George Engel, who developed this paradigm—originally in reference to the scope and conduct of biomedicine—to describe humans as biological organisms, who psychologically experience and respond to the social (i.e., physical, group, economic, political) environment(s) in which they are embedded and function.

This whitepaper, Assessing and Anticipating Threats to US Security Interests: A Bio-PsychoSocial Science Approach for Understanding the Emergence of and Mitigating Violence and Terrorism represents the work of intra- and extramural subject matter experts (SMEs) from multiple disciplines, convened to provide views and insights to define and further develop a bio- psychosocial approach to understanding, assessing, and influencing the cognitions and behaviors of individuals and groups that are devising, recruiting, training, and implementing organized aggression and violence. In light of current national and international security concerns, a major focus of this report is upon those bio-psychosocial factors that are influential to, and influenced by the activities of the group known as Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant— ISIL (or Daesh/Da’ish).

The report is formally divided into five (5) sections:

- Introduction; and Review of Related SMA Projects/Work;

- Biological Perspectives On Behavior;

- Psychological Perspectives On Behavior;

- Social Perspectives On Behavior; and

- Operational Perspectives.

Following the Introduction and Review of Related SMA Projects, each section has been developed in a way such that the reader may delve into each/any of the sections to gain both an overview and subsequently more finely-grained, detailed insight to (biological, psychological, and/or social) aspects of individual and/or group aggression and violence. In keeping with the core principles of the bio-psychosocial model, these sections are interactive and reciprocal.

The reader need not proceed in any particular order, but may elect to begin with any section, so as to gain understanding of how and why certain (biological, psychological, or social) dimensions affect, and are affected by others. In each chapter, reference is made to information in/of other chapters, and the reader can use these references as direction to find related and supportive information. The final section of this report affords an overall operational perspective.

Thus, if and when taken either in part or in sum, this report will provide a working view to the ways that bio-psychosocial variables—and a bio-psychosocial approach—are important to understanding aggression and violence, and informing and articulating national security, intelligence, and defense efforts to analyze, deter, and/or prevent its incitement and occurrence.

NSI Chapters:

- A Review Of SMA Bio-Psycho-Social Investigations (S. Canna)

- Understanding The Social Context: Following Social And Narrative Change Via Discourse And

Thematic Analysis Surrounding Daesh In The Middle East (L. Kuznar)

Contributing Authors

Canna, S. (NSI), Casebeer, W. (Lockheed Martin), Chen, C. (Georgetown University), DiEuliis, D. (National Defense University), Eyre, D. (System of Systems Analytics), Fenstermacher, L. (Air Force Research Laboratory), Giordano, J. (Georgetown University Medical Center), Hogg, J. (Fielding Graduate University), Kuznar, L. (Indiana University – Purdue University Fort Wayne, NSI), Ligon, G. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Linera, R. (USASOC), Martin, M. (USASOC), McCauley, C. (Bryn Mawr College), McRoberts, M. (Department of Defense), Morin, C. (Fielding Graduate University), Morrison, B. (University of British Colombia), Moskalenko, S. (Bryn Mawr College), Otwell, R. (USASOC), Rogers, P. (Bradford University), Romero, V. (Information Science Technology Research), Seese, G. (USASOC), Rutledge, P. (Fielding Graduate University), Spitaletta, J. (Joint Staff/J7 & Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Laboratory), Stangle, R. (USASOC), Suedfeld, P. (University British Colombia), Wright, N. (University of Birmingham & Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), Wurzman, R. (University of Pennsylvania).Votel, J. (USSOCOM)

Question (V7): Objectives and Motivations of Indigenous State and Non-State Partners In the Counter-Isil Fight. What are the strategic objectives and motivations of indigenous state and non-state partners in the counter-ISIL fight?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

The following are high-level results of a study assessing Middle East regional dynamics based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolve. Expected outcomes are based on the strategic interests of regional actors.

ISIL will be defeated in Syria and Iraq

Based on the balance of actor interests, resolve and capability, the defeat of Islamic State organization seems highly likely (defeat of the ideology is another matter). Specifically, the push for ISIL defeat in Syria is led by Iran and the Assad regime, both of which have high potential capacity and high resolve relative to ISIL defeat. Only ISIL has high resolve toward ISIL expansion in Syria. Iran, Jordan,Iraqi Kurds, Saudi Arabia, and Shi’a Hardline & Militia, show highest resolve for ISIL defeat in Iraq.

Conflict will continue in Syria following ISIL defeat; will escalate significantly with threat of Assad defeat

Whether Syrian civil conflict will cease in the context of an ISIL defeat is too close to call. Assad, Russia and Iran have strong untapped capability to drive an Assad victory against the remaining Opposition although none show high resolve (i.e., the security value gained by an Assad victory versus continued fighting in Syria is not widely different. This reflects the Assad regime’s competing security interests (i.e., one interest is better satisfied by continued conflict, another by Assad victory). Even when we assume the defeat of ISIL in Syria as a precondition, unless actor interests change dramatically, the number of interests served by continued conflict and the generally low resolve on both sides suggests that we should be skeptical of current agreements regarding the Syrian Civil War. Moreover, resolve scores rise sharply when continued conflict is replaced by the possibility of Assad defeat. Together these results suggest that unless Assad’s, Iran’s and Russia’s perceived security concerns are altered significantly, these actors have both the capacity and will to engage strongly to avoid an impending defeat. The high resolve of the three actors to avoid defeat should be taken as a warning of their high tolerance for escalation in the civil conflict.

Implication: Tolerating Russian-Iranian military activities in Syria and redirecting US resources to humanitarian assistance of refugees in and around Syria has greater value across the range of US interests and aligns more fully with the balance of US security interests in the region.

GoI lacks resolve to make concessions to garner support from Sunni Tribes

While the majority of regional actors favor the Government of Iraq (GoI) making concessions to Sunni and Kurdish groups following defeat of ISIL, only the Government of Iraq, Shi’a Hardline and Militia, Sunni Tribes and Iraqi Kurds have significant capability to cause this to happen or not. Unfortunately, the GoI and Shi’a have high resolve to avoid reforms substantive enough to alter Sunni factions’ indifference between GoI and separate Sunni and/or Islamist governance. More unfortunately, when they believe the GoI will not make concessions, Sunni Tribes are indifferent between ISIL governance and the current Government controlling Iraq. That is, they have no current interest served by taking security risks associated with opposing ISIL. However, the outbreak of civil warfare in Iraq does incentivize GoI to make concessions. Iranian backing of substantial GoI reforms changes the GoI preference from minimum to substantive reforms without the necessity of civil warfare.

Implication: Now is the opportune time to engage all parties in publically visible dialogue regarding their views and requirements for post-ISIL governance and security. Engaging Sunni factions on security guarantees and requirements for political inclusion/power is most likely to be effective; Engaging Kurds on economic requirements and enhancing KRG international and domestic political influence encourage cooperation with GoI. Finally, incentivize Iran to help limit stridency of Shi’a hardline in Iraq eases the way for the Abadi government to make substantive overtures and open governance reform talks.

Saudi Arabia-Iran Proxy funding continues; easily reignites conflict

Use of proxy forces by Saudi Arabia and Iran is one of the quickest ways to reignite hostilities in the region, and even though direct confrontation between state forces is the worst outcome for both, the chances of miscalculation leading to unwanted escalation are very high. Both Saudi Arabia and Iran have high resolve to continue supporting regional proxies up to the point that proxy funding or interference prompts direct confrontation between state forces. This is driven by mutual threat perception and interest in regional influence. This leaves open the specter that any conflict resolution in the region could be reignited rapidly if the incentives and interests of the actors involved are not changed.

Implication: International efforts to recognize Iran as a partner, mitigate perceived threat from Saudi Arabia and Israel, and expand trade relations with Europe are potential levers for incentivizing Iran to limit support of proxies. Saudi Arabia may respond to warning of restrictions on US support if proxyism is not curtailed.

Contributing Authors

Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI), Berti, B. (Institute for National Security Studies, Tel Aviv; Fellow, Foreign Policy Research Institute), Bragg, B. (NSI), Brom, S. (Center for American Progress), Canna, S. (NSI), Gengler, J. (Qatar University), Hassan, H. (Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy), Hecker, M. (Institut Français des Relations Internationales), Khashan, H. (American University of Beirut), Kuznar, L. (NSI), Lynch, T. (National Defense University), Popp, G. (NSI), Rumer, E. (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), Tenenbaum, E. (Institut Français des Relations Internationales), Thomas, T. (Foreign Military Studies Office, Ft. Leavenworth); Vatanka, A. (Middle East Institute, The Jamestown Foundation), Weyers, J. (iBrabo; University of LIverpool), Yager, M. (NSI)

Question (R3 QL3): What are the aims and objectives of the Shia Militia Groups following the effective military defeat of Da’esh?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Referring to the Shi’a Militias as a unitary or homogenous entity masks the reality that what are now dozens of groups in Iraq were established at different times and for different reasons, and thus have different allegiances and goals. 1 Dr. Daniel Serwer of Johns Hopkins SAIS puts it succinctly, “Not all ‘Shi’a militia groups’ are created equal.” An actor’s defining characteristics have a significant impact on the objectives it pursues. The expert contributors highlight two factors we might use to differentiate the many Shi’a militia groups in Iraq, their aims, objectives and likely post-ISIS actions. These are: 1) the extent to which the group is led by and owes allegiance to Iran; and 2) the span of its concerns and interests. How groups rate on these two factors will tell us a lot about what we should expect of them following the effective defeat of ISIS (see graphic).

Autonomy. Contributors to this Quick Look tended to differ on where the balance of control over the Shi’a militias rests. Some see the Shi’a PMF groups as primarily under the control of Iran, and thus motivated or directed largely by Iranian interests (i.e., they have very little autonomy.) If this is the case, knowing the interests of the leaders of these groups will tell us little about their actions). Other experts view the militias as more autonomous and self- directed albeit with interests in common with Iran in which case their interests are relevant to understanding their objectives. In reality, there are groups that swear allegiance to the Supreme Leader in Iran, those that follow Ayatollah al Sistani, and still other groups that respond only to their commanders. In an interview with the SMA Reachback team, Dr. Anoush Ehteshami a well-known Iran scholar from Durham University (UK) points out that Iran has “shamelessly” worked with groups it controls as well as those that it does not because it sees each variety as a “node of influence” into Iraqi society. As in previous Reachback Quick Looks2, a number of the SMEs note that Iran is best served by taking a low- key approach in Iraq. Ehteshami argues that ultimately Iran has little interest in appearing to control the Shi’a militias: “the last thing that they want is to be seen as a frontline against Daesh” as this would reinforce the Sunni versus Shi’a sectarian, Saudi-Iranian rivalry undercurrents of the conflict against ISIS. In fact he argues that Iran prefers to work with the militias rather than the central government – which is susceptible to political pressure that Iran cannot control in order to “maintain grass root presence and influence … of the vast areas of Iraq which are now Shia dominated.”

Ambition. A second factor that distinguishes some militia groups is the span of their key objectives and ambition. In discussing militia objectives, some SMEs referenced groups with highly localized interests, for example groups that were established more recently and primarily for the purpose of protecting family or neighborhood. Others mentioned (generally pro-Iran) groups with cross-border ambitions. However, the major part of the discussion of militia objectives centered on more-established and powerful groups with national-level concerns.

Key Objectives

Most experts mentioned one or all of the following as key objectives of the Shi’a militia, at present and in post-ISIS Iraq. Importantly, many indicate that activities in pursuit of these objectives are occurring now – the militias have not waited for the military defeat of ISIS.

Controlling territory and resources

For groups with very localized concerns this objective may take the form of securing the bounds of an area, or access to water in order to protect family members or neighborhoods. For groups with broader ambitions, American University of Iraq Professor Christine van den Toorn argues that controlling territory and resources is a means to these militias’ larger political goals. As in the past, this may entail occupying or conducting ethnic cleansing of areas of economic, religious and political significance (e.g., Samarrah, Tel Afar, former Sunni areas of Salahuldeen Province near Balad.) Here too Anoush Ehteshami suggests that different militia groups have different allegiances and motives: some are “keen to come flying a Shia flag into Sunni heartlands and are determined to take control of those areas.” A number of authors indicate that a specific project of Iran-backed militias possibly with cross-border ambitions would be to secure Shi’a groups’ passage between Iraq and Syria (van den Toorn suspects this would be north or south of Sinjar adding that Kurds would prefer that the route “go to the south, through Baaj/ southern Sinjar and not through Rabiaa, which they want to claim.”)

Consolidating political power and influence

Anoush Ehteshami believes that the Shi’a militia groups are keen to gain as much “control of government as possible, as quickly as possible.” These groups are actually new to Iraqi politics and realize that once the war is over their influence and role in the political order may end. Many of the experts identified the primary objective of militia groups with broader local or national ambitions as increasing their independence from, and power relative to Iraqi state forces. Christine van den Toorn relates an interesting way that some Shi’a militias are working to expand their influence: by forging alliances with “good Sunnis” or “obedient Sunnis.” In fact, she reports that the deals now being made between some Sunni leaders and Shia militia/PMF are in essence “laying the foundation of warlordism” in Iraq and potentially cross-nationally. Many experts singled out the law legalizing the militias as making it “a shadow state force” or an Iraq version of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (RGC) – a clear victory for those seeking to institutionalize the political wealth, and likely economic wealth of the militias.

Dr. Harith Hasan al-Qarawee of Brandeis University agrees that the primary goal of the militia groups with national or cross-national ambitions is to gain political influence in Iraq in order to: “to improve their chances in the power equation and have a sustained access to state patronage.” As a result, he anticipates that they will continue to work to weaken the professional, non-sectarian elements of the Iraqi Security Forces, and would accept reintegration into the Iraqi military only if it affords them the same or greater opportunity to influence the Iraqi state than what they currently possess. Finally, a number of the experts including Dr. Randa Slim of the Middle East Institute, mention that an RGC-like, parallel security structure in Iraq will also serve Iran as a second “franchisee” along with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and allow export of “military skillsets/expertise/knowhow, which can be shared with fellow Shia groups in the Gulf region.”

Eliminating internal opposition from Sunni and Kurds

Omar Al-Shahery, a former deputy director in the Iraqi Defense Ministry, along with a number of other SME contributors believe that after the Sunni Arabs are “taken out of the equation” the Kurds are the militias’ “next target.” Dr. Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins SAIS) expects that Shi’a forces will remain in provinces that border Kurdistan, if not at the behest of Iran, then certainly in line with Iran’s interest in avoiding an expanded and independent Kurdistan in Iraq. Al Shahery (Carnegie Mellon) points to this as the impetus for militias pushing the Peshmerga out of Tuzkurmato south of Kirkuk. Similarly, Shi’a concern with Saudi support reaching Sunni groups opposed to the expansion of Shi’a influence in Iraq was motivation for occupying Nukhaib (south Anbar) and cutting Sunni forces off from a conduit to aid. Finally, Al-Shahery raises the possibility that the ultimate goal of the most ambitious militia groups is in fact to form an “integrated strike force” that can operate cross-nationally. This is evidenced he argues, by the centralization of the command structure of the forces operating in Syria.

What to Expect after Mosul

The following are some of the experts’ expectations about what to expect from the Shi’a militias in the short to mid-term. See the author’s complete submission in SME input for justification and reasoning.

- Re-positioning. Iran will encourage some militia forces to relocate to Syria to help defend the regime. However, Iran also will make sure that the “Shia militias which have been mobilized, are going to stay mobilized” as a “pillar of Iran’s own influence in Iraq” (Dr. Anoush Ehteshami, Durham University, UK)

Following ISIS defeat in Iraq …

- Inter and intra- sectarian conflict. The PMFs will play a “very destabilizing” role in Iraq if not disbanded or successfully integrated into a non-sectarian force. The present set-up will result in renewed Sunni-Shia tensions, Sunni extremism (Dr. Monqith Dagher, IIACSS and Dr. Karl Kaltenthaler, University of Akron); Shi’a-Shi’a violence (Dr. Sarhang Hamasaeed, USIP); and/or violent conflict with the Kurds (Dr. Daniel Serwer, Johns Hopkins SAIS; Omar Al-Shahery, Carnegie Mellon)

- New political actors. Select militia commanders will leave the PMF to run for political office, accept ministerial posts (Dr. Daniel Serwer, Johns Hopkins SAIS) and/or “major political players in Baghdad” will attempt to place them in important positions in the police or Iraqi security force positions. (Dr. Diane Maye, Embry-Riddle)

Contributing Authors

Ford, R. (Middle East Institute), Slim, R. (Middle East Institute), Abouaoun, E. (US Institute of Peace); al-Qarawee, H. (Brandeis University), Al-Shahery, O. (Carnegie Mellon University), Atran, S. (ARTIS), Dagher, M. (IIACSS), Gulmohamad, Z. (University of Sheffield), Ehteshami, A. (Durham University), Kaltenthaler, K. (University of Akron), Mansour, R. (Chatham House), Hamasaeed, S. (US Institute of Peace), Maye, D. (Embry Riddle University), Nader, A. (RAND), Serwer, D. (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies), van den Toorn, C. (American University of Iraq, Sulaimani), Wahab, B. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy)