SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Question (V6): Strategic and Operational Implications of the Iran Nuclear Deal. What are the strategic and operational implications of the Iran nuclear deal on the US-led coalition¹s ability to prosecute the war against ISIL in Iraq and Syria and to create the conditions for political, humanitarian and security sector stability?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Prior to the signing of the Iran Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July 2014, Iran watchers tended to anticipate one of two outcomes. One camp expected a reduction in US-Iran tensions and that the JCPOA might present an opening for improved regional cooperation between the US-led coalition and Iran. The other camp predicted that Iran would become more assertive in wielding its influence in the region once the agreement was reached.

Implications of JCPOA for the Near-term Battle: Marginal

Iran experts in the SMA network generally believe that JCPOA has had negligible, if any, impact on Iran’s strategy and tactics in Syria and Iraq.1 While Iran does appear to have adopted a more assertive regional policy since the agreement, the experts attribute this change to regional dynamics that are advantageous to Iran, and Iran having been on “good behavior during the negotiations” rather than to Iran having been emboldened by the JCPOA. Patricia Degennaro (TRADOC G27) goes a step further. In her view, the impact of the JCPOA on the battle against ISIL is not only insignificant, but concern about it is misdirected: “the JCPOA itself will not impede the Coalition’s ability to prosecute the war … and create the conditions for political, humanitarian and security sector stability. Isolation of Iran will impede the coalition’s mission.”

Richard Davis of Artis International takes a different perspective on the strategic and operational implications of the JCPOA. He argues that Saudi, Israeli and Turkish leaders view the JCPOA together with US support for the Government of Iraq as evidence of a US-Iran rapprochement that will curb US enthusiasm for accommodating Saudi Arabia’s and Turkey’s own regional interests. Davis expects that this perception will “certainly manifest itself in the support for proxies in Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Specifically, it means that Saudi Arabia and Turkey will likely be more belligerent toward US policies and tactical interests in the fight to defeat ISIL.”

Implications of JCPOA for Post-ISIL Shaping: Considerable Potential

The SMA experts identified two ways in which the JCPOA could impact coalition efforts to stabilize the region in the mid- to longer-term: 1) if Iran were to use it as a means of generating friction in order to influence Coalition actions for example by convincing Coalition leaders that operations counter to Iranian interests (e.g., in Syria) could jeopardize the JCPOA; and, 2) indirectly, as having created the sanction relief that increases Iranian revenue and that can be used to fund proxy forces and other Iranian influence operations.

Provoking Friction as a Bargaining Chip. A classic rule of bargaining is that the party that is more indifferent to particular outcomes has a negotiating advantage. At least for the coming months, this may be Iran. According to the experts, Iran is likely to continue to use the JCPOA as a source of friction – real, or contrived – to gain leverage over the US and regional allies. The perception that the Obama Administration is set on retaining the agreement presents Tehran with a potent influence lever: provoking tensions around implementation or violations of JCPOA that look to put the deal in jeopardy, but that it can use to pressure the US and allies into negotiating further sanctions relief, or post-ISIL conditions in Syria and Iraq that are favorable to Iran. However, because defeat of ISIL and other groups that Iran sees as Saudi-funded Sunni extremists,2 the experts feel that if Iran were to engage in physical or more serious response to perceived JPCOA violations, they would choose to strike out in areas in which they are already challenging the US and Coalition partners (e.g., at sea in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea; stepping up funding or arms deliveries to Shiite fighters militants in Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Yemen) rather than in ways that would actually impede ISIL’s defeat.

Increased Proxy Funding. Iran has often demonstrated a strategic interest in maintaining its influence with Shi’a communities and political parties across the region, including of course, providing support to Shi’a militia groups (Bazoobandi, 2014).3 Pre-JCPOA sanctions inhibited Iran’s ability to provide “continuous robust financial, economic or militarily support to its allies” according to Patricia Degennaro (TRADOC G27). An obvious, albeit indirect implication of the JCPOA sanctions relief for security and political stability in Iraq in the longer term is the additional revenue available to Iran to fund proxies and conduct “political warfare” as it regains its position in international finance and trade.4 It will take time for Iran to begin to benefit in a sustainable way from the JCPOA sanctions relief. As a result it is not as likely to be a factor in Coalition prosecution of the wars in Iraq and Syria, but later, in the resources Iran can afford to give to both political and militia proxies to shape the post-ISIL’s region to its liking.

Contributing Authors

DeGennaro, P. (Threat Tec, LLCI -TRADOC G27), Nader, A. (RAND), Eisenstadt, M. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Knights, M. (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Alex Vantaka (Jamestown Foundation)

Question (R3 #2): How does Da’esh’s transition to insurgency manifest itself, and what actions should the Coalition take to minimize their ability to maintain either military effectiveness or popular support?

Author | Editor: DeGennaro, P. (TRADOC G-2/G-27).

The self-proclaimed Islamic State (IS) or Da’esh, as the group has become known, transition to insurgency is underway. They may not see it like this since Iraq and Syria are struggling with their own sovereignty and trying to restructure governance to support the basic necessities of the populations.

Daniel Serwer of Johns Hopkins University says we can already see this manifesting “in overt terrorist attacks, which are already frequent, as well as more covert intimidation.” IS is conducting suicide, IED and infrastructure attacks daily. The group will continue to be active in organized crime activities – protection rackets, smuggling of oil and antiquities, kidnapping for ransom, and violent intimidation – against any effort to restore law and order. “Daesh will not fold its tent. It may even spawn a new organization to carry on its campaign for the caliphate and seek to embed with other less brutal Salafists,” says Serwer.

In light of the possibility that U.S. backed Iraqi and Peshmerga forces are pushing IS out of its territory in Iraq and beginning to tackle some locations in Syria, Harith Al-Qarawee, professor at Brandeis University, says, “ISIS insurgents who will survive the Mosul battle will return to underground insurgency and seek to secure safe passages between Iraq and Syria.” He and other experts agree that there must be an effective intelligence effort in urban centers to keep abreast of any movements IS may make if another gap in security and governance should open up. Renad Mansour, an expert at Chatham House, reminds us they IS will continue, even underground to “make sure that Iraq’s political elite are unable to come up with a political solution,” so if a political solution is not found, IS will use this as a reason to resurface. The last U.S. Ambassador to Syria, Ambassador Robert Ford, and Elie Abouaoun, at USIP, feel that in order to prevent this from happening, “a genuine and organic national reconciliation effort” must commence by investing in political reconciliation initiatives that combine both top-down and bottom-up approach and include a regional dialogue between Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

SMEs agree that IS will not disappear. They will most likely go into hiding with sleeper cells in Iraqi and Syrian cities. Many may also remain silent in other Western countries looking for future opportunities to act. Noted anthropologist Scott Atran believes IS “will retreat to its pre-Caliphate tactics, as they did during the Iraqi surge, when they lost 60-80% of their foot soldiers and more than a dozen high-value targets each month for 15 consecutive months, yet still survived with a strong enough organization to seize the initiative in the chaos of the Syrian Civil War and roar back along the old oil-for-smuggling routes that Sunni Arab tribesmen and Saddam loyalists.” Randa Slim of the Middle East Institute states that, “there will be post-ISIS territorial and ideological challenges. On the territorial side of the equation, given the range of actors involved in the Mosul fight, there will be increasing stakes, post-liberation, of competing territorial claims between Baghdad and Erbil but also among different ethnic groups. She continues, “Kirkuk is likely to be a major point of competition in the future and will complicate the relationship between Erbil and Baghdad” and losing territory will undermine ISIS’s caliphate narrative.”

All agree that the Iraqi leadership must find a way to bring the Sunni population into the political decision making by cultivating local leaders who have legitimacy and credibility. Sunni groups, that are particularly fragmented, must contribute to reconstruction of liberated territories and participate in security, police and military, to ensure that their grievances are met. These grievances are rooted in divisions that are embedded by continued attacks on their communities by IS, who are dividing Sunnis as well as Sunnis and Shia populations, and Shia forces perceived to be targeting not only Iraqi Sunnis, but all Sunnis as a proxy for Iran.

Many “IS members are Iraqis,” says Bilal Wahab of the Washington Institute, who were brutally coerced to join IS or had little economic choice, they too should be a focus for immediate reintegration into society to help quell animosities perpetuated in this conflict. Remember, says Altran, “many of the leaders of the Sunni Arab militia in Mosul supported IS at the outset (as “The Revolution” – al Thawra – to win back Iraq from Shia control) and turned against IS when they encourage Sunni to go against Sunni. “Military action and humanitarian assistance are critical, but they are mostly addressing the symptoms, and need to be supplemented by civilian initiatives” says United States Institute of Peace expert Sarhang Hamasaeed. In Diane Maye’s words, “An important element of denying regrowth is to use targeting in conjunction with a broader movement to engage the population against the terrorist network.” In other words, take advantage of an IS retreat by rebuilding and improving the livelihoods of people. That is the main IS deterrent.

Bilal Wahab, Washington Institute, encourages coalition members to take into account several lessons from the past when planning next steps. First, “If grievances continue—mass arrests, kidnappings and economic sidelining, insurgency will remain legitimate in the eyes of the population” and second, “cash speaks louder than ideology, be it foreign funds pouring into Iraq, or Sunni politicians funneling money into violent groups to gain leverage in Baghdad. Finally, “in addition to sectarianism, a chronic malaise of Iraq’s security forces is corruption and has impunity.” This must be addressed immediately. Trust in security forces is the only way populations will support and report ongoing IS activities.

Contributing Authors

Abouaoun, E. (United States Institute of Peace), Atran, S. (ARTIS), Al-Qarawee, H. (Brandeis University), Al-Shahery, O. (Aktis), Ford, R. (Middle East Institute), Hamasaeed, S. (United States Institute for Peace), Ligon, G. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Logan, M. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Mansour, R. (Chatham House); Maye, D. (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University); McCauley, C. (Bryn Mawr College), Meredith, S. (National Defense University), Mironova, V. (Harvard University), Serwer, D. (Johns Hopkins University), Slim, S. (Middle East Institute), Wahab, B. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Whiteside, C. (Naval Postgraduate School)

Mosul Coalition Fragmentation: Causes and Effects.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc) & Krakar, J. (TRADOC G-27).

This paper assesses the potential causes and effects of fragmentation on the Counter-ISIL coalition. This coalition consists of three distinct but interrelated subsets:

- the CJTF-OIR coalition;

- the regional coalition, de facto allies of convenience, who may provide any combination of money, forces or proxies;

- the tactical coalition, the plethora of disparate groups fighting on the ground.

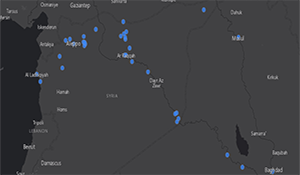

The study team assessed how a change in either the CJTF-OIR coalition or regional coalition could influence the tactical coalition post Mosul and the subsequent effect of these potential fragmentations on the GoI¹s ability to control Iraq. The study team established six potential post-Mosul future scenarios. One future consisted of the tactical coalition remaining intact and the other five consisted of different permutations of the tactical coalition fragmenting. The study team then modeled these six futures with the Athena Simulation and quantified their effects on both Mosul and Iraq writ large.

During simulation these six fragmentation scenarios collapsed into two distinct outcomes: one in which GoI controlled Mosul and one in which local Sunni leadership controlled Mosul. The variable that determined the outcome was the involvement of the Sunnis in the post-Mosul coalition—if the local Sunni leadership remained aligned with the GoI, the GoI remained in control of Mosul. If the local Sunni leadership withdrew from the coalition the GoI lost control of Mosul and the local Sunni leadership assumed control of Mosul—regardless of whether any other groups left the coalition. Irrespective of the local Sunni leadership’s involvement in the coalition the GoI was able to maintain control of everything but Mosul and the KRG controlled areas of Iraq. This included historically Sunni areas of Al Anbar including Fallujah and Ramadi.

While several permutations of the regional coalition fragmenting may take place, the centrality of the Sunnis to any outcome puts the actions of the GoI to forefront. PM Abadi’s desire to preserve the unity of Iraq may position the GoI at odds with calls for increased local autonomy from some factions of Kurdish and Sunni leaders. In the event of the chaos that would characterize violent civil conflict among Kurdish, Sunni and Shi’a forces—likely with proxy support from Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran respectively—the multi-ethnic, multi-sect members of the Iraqi Army and police will be hard pressed to know which battles to fight and more than breaking with the coalition outright, may for reasons of confusion and self-preservation simply fall and recede as effective fighting forces.

Operating in the Human Domain 1.0.

Author | Editor: U.S. Special Operations Command.

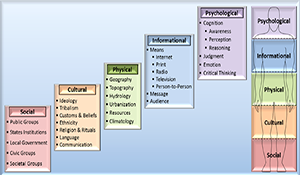

Building on the vision of USSOCOM strategic guidance documents, the Operating in the Human Domain (OHD) Concept describes the mindset and approaches that are necessary to achieve strategic ends and create enduring effects in the current and future environment. The Human Domain consists of the people (individuals, groups, and populations) in the environment, including their perceptions, decision-making, and behavior. Success in the Human Domain depends on an understanding of, and competency in, the social, cultural, physical, informational, and psychological elements that influence human behavior.2 Operations in the Human Domain strengthen the resolve, commitment, and capability of partners; earn the support of neutral actors in the environment; and take away backing and assistance from adversaries. If successful in these efforts, Special Operations Forces (SOF) will gain military, political, and psychological advantages over their opponents. The OHD Concept integrates existing capabilities and disciplines into an updated and comprehensive approach that is applicable to all SOF core activities.

SOF personnel continuously think about human interactions, building trust, and winning support among individuals, groups, and populations. Drawing on the approach and required capabilities identified in this concept, SOF and its partners use persuasion and compulsion to shape the calculations, decision-making, and behavior of relevant actors3 in a manner consistent with mission objectives and the desired state.4 SOF must win support and build strength, before confronting adversaries in battle. Working in collaboration with capable partners and as part of a whole-of-government approach, SOF enables preemptive actions to avert conflicts or keep them from escalating. When necessary, SOF and its partners confront and defeat adversaries, always mindful that the end goal is an eventual cessation of hostilities and a more sustainable peace.

SOF conduct enduring engagement in a variety of strategically important locations with a small-footprint approach that integrates a network of partners. This engagement allows SOF personnel to nurture relationships prior to conflict. Language and cultural expertise are important, but SOF’s ability to shape broader campaigns with allies and partners to promote stability and counter malign influence is vital. SOF leaders plan and execute operations that support national objectives, while providing continuous analysis and advice to ensure effective strategy. SOF must identify and assess relevant actors, understand their past and current decisions and behavior, and anticipate and influence their future choices and actions across the ROMO.

SOF contribute to the accomplishment of U.S. policy objectives during peaceful competition, non-state and hybrid conflicts, and wars among states. The ideas in the OHD Concept are key to confronting state and non-state actors that combine conventional and irregular military force as part of a hybrid approach. Adversary states are increasingly adapting their methods to negate current and future U.S. strengths, relying on non-traditional strategies, including the use of subversion, proxies, and anti- access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. These adversary strategies require a refined U.S. approach for effective counteraction. A critical goal will be to create conditions that shape adversary decisions and behavior in a manner that favors U.S. objectives or develops opportunities friendly forces can exploit to achieve the desired state.

Eurasia Strategic Risk.

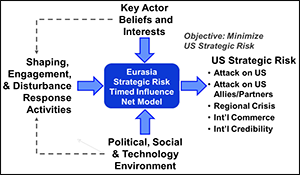

Author | Editor: Elder, R. & Levis, A. (GMU).

The GMU Eurasia Strategic Risk project examined future political, security, societal and economic trends as they apply to the decision calculus of key Eurasian regional actors. Timed Influence Net (TIN) models were used to identify potential sources of strategic risk for the United States by focusing on actions and behaviors that would be considered adverse by the United States, NATO, and other U.S. partner nations. The goal was to provide planners with a tool that can be used to inform their discussions with military and non-military staffs from both the United States and its partners on potential Eurasia strategies. Among the key observations: When the adverse behaviors the United States seeks to influence are not related to a perceived existential threat to a NATO member, classical deterrence cost-benefit calculations lose importance. However, Russia’s perceived cost-benefit calculations of not acting, and its perception of the decision calculus of the United States and its partners remain important considerations. For this reason, the study concludes that NATO’s Article V will continue to serve as an effective deterrent to actions which the Alliance believes constitute an existential threat to a member country, but is less likely to deter attacks that do not jeopardize a member state’s existence because the political cost of restraint for Russia outweighs the potential cost of a likely NATO response.

Conclusions and Recommendations

NATO’s Article V will continue to serve as an effective deterrent to actions which the Alliance believes constitute an existential threat to a member country, but is less likely to deter attacks that do not jeopardize a member state’s existence: the political cost of restraint outweighs the potential cost of a likely NATO response. However, NATO can favorably influence Russia’s decision calculus for adverse behaviors that do not constitute existential threats by focusing on (1) reducing the cost (and increasing the benefit) of exercising restraint, and (2) altering Russia’s perception of the US/NATO decision calculus so that it does not assess that it must act to preempt US and NATO actions during periods of instability.

The US and NATO can influence Russia’s view of its strategic deterrence posture by using all the levers influencing the Russian strategic posture decision calculus: Increase perceived cost of action (punishment), reduce perception that Russia will benefit from the action, reduce perceived cost of restraint, increase perceived benefit of restraint, and positively influence the Russian perception of United States and NATO objectives in a crisis.

Since the Russian narrative implies that the West will exploit every opportunity to reduce Russian power and status, the United States should avoid behaviors and discourage partner actions that support the anti-Russian narrative. De-escalation of a potential crisis becomes increasingly difficult once the Russian leadership rallies the Russian electorate and their partners outside Russia; therefore, where possible, the United States should focus on Russia’s perceived costs and benefits of exercising restraint when assessing ways to motivate Russian actions to reduce US strategic risk in the EUCOM AOR.

Although the study did not conduct experimentation on the potential for theater engagement and security cooperation to reduce potential strategic risk in the EUCOM AOR, it seems clear that it will be extremely difficult to alter Russian core beliefs regarding the motives of the United States and NATO with respect to its power and international prestige. The United States is capable of influencing the attitudes and behaviors of other regional actors, to include former Russian clients, through its shaping and engagement activities. These attitudes and behaviors become important when regional stability is disturbed and responses to the disturbance are implemented. It is important for all pertinent parties to avoid activities reinforcing the Russian narrative that believes the United States and its allies will exploit every opportunity to diminish Russian power and status.

Question (V5): Factors that Will Influence the Future of Syria. What are the factors that will influence the future of Syria and how can we best affect them?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Experts varied from pessimistic (chronic warfare) to cautiously optimistic regarding their expectations for the future of Syria, yet mentioned many of the same factors that they felt would influence Syria’s future path. Most of these key factors – ranging from external geopolitical rivalries to the health and welfare of individual Syrians – were outside what typical military operations might affect. Instead they center on political and humanitarian recovery, healing of social division.

External Factor: the use of Iranian, Saudi proxies in Syria

Iranian and Saudi use of proxy forces is one of the wild-cards in the future of Syria and is probably quickest way to reignite violence in the wake of any cease-fire or negotiated settlement. In fact, the intensity of the Iran-Saudi regional power struggle and how this might play out in Syria was the factor most mentioned by the SMA experts.

Encouraging the conditions necessary for stability in Syria requires discouraging Iran-Saudi rivalry in Syria. This can be done in a number of ways including offering for security guarantees or other inducements to limit proxyism in Syria (e.g., for Iran promise of infrastructure reconstruction contracts). Unfortunately, Iran stands to have greater leverage in Syria following the war, regardless of whether Assad stays or goes. If Assad or loyalist governors remain in Syria they will be dependent on Iran (and Russia) for financial and military support. As Yezid Sayigh (Carnegie Middle East Center) writes, “even total victory leaves the regime in command of a devastated economy and under continuing sanctions.” Still, if Assad is ousted and Iranian political influence in the country wanes, its economic influence in Syria should remain strong. Since at least 2014 Iran, the region’s largest concrete producer has been positioning itself to lucrative gain post-war infrastructure construction contracts giving it significant influence over which areas of Syria are rebuilt and which groups would benefit from the rebuild. Under these conditions, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and/or Turkey could ramp up their efforts to contain Iranian influence by once again supporting aggrieved Sunni extremists. This would be all the more likely, if as Josh Landis predicts, “Assad, with the help of the Russians, Chinese, Iraqis and Hezbollah, will take back most rebel held territory in the next five years.”

External Factor: the degree of Coalition-non Coalition agreement on the governance and security conditions of post-war Syria

Lt Col Mel Korsmo an expert in civil war termination from Air University concludes that a negotiated settlement is the best path to political transition and resolution of the civil conflict in Syria. Others felt that any resolution of the Syrian civil conflict would depend on broad-based regional plus critically, US and Russian (and perhaps Chinese) agreement on the conditions of that resolution. The first question is whether there remain any elements of 2012 Geneva Communiqué or UN Security Council resolution 2254 which endorsed a roadmap for peace in Syria that might be salvaged. Lacking agreement among the major state actors, the authors expected that proxy warfare would continue in Syria. Moshe Ma’oz (Hebrew University) and others however argued that it may be too late for the US to wield much influence over the future path of Syria; it has already ceded any leverage to Russia and Iran. Others argue that the way the US might regain some leverage is by committing to the battle against Assad with the same effort given to defeating ISIL. Nevertheless, there is general agreement that it is imperative to attempt now to forge agreement on the clearly- stated steps to implementing a recovery plan for Syria.

External Factor: US and Coalition public support for sustained political, security and humanitarian aid for Syria

Another condition that must be met if the US and Coalition countries are to have impact on political and social stability in Syria is popular support for providing significant aid to Syria over an extended period of time. This may be a tall order, particularly in the US where the public has long thought of Syria as an enemy of Israel and the US in the Levant. Compounding this, the experts argue that when warfare comes to an end in Syria the regime will be so dependent on Russia (and Iranian) aid, that the Syrian government will lose its autonomy of action. While encouraging Americans to donate to charitable organizations aiding Syrian families may not be too difficult, gaining support for sustained US government assistance in the amounts and over the length of time required is likely to be a significant challenge. It is also one that could be quickly undermined by terror attacks emanating from the region.

Internal Factor: the role of Assad family

Osama Gharizi of the United States f Peace points to the “‘current strength and cohesion” of the Syrian opposition and argues that a “disjointed, weakened, and ineffectual opposition is likely to engender [an outcome] in which the Syrian regime is able to dictate the terms of peace” –a situation which would inevitably leave members of the family or close friends of the regime in positions of power. Unfortunately, many of the experts believe that while there may be fatigue-induced pauses in fighting, as long as the Assad family remains in power in any portion of Syria civil warfare would continue. Furthermore separating Syria into areas essentially along present lines of control would leave Assad loyalists and their Iranian and Russian patrons in control of Damascus and the cities along the Mediterranean coast with much of the Sunni population relegated to landlocked tribal areas to the east. Such a situation would further complicate the significant challenge of repatriating millions of internally displaced persons (IDPs), many of whom lived in the coastal cities.

Acceding to Assad family leadership over all or even a portion of Syria is unlikely to offer a viable longer-term solution, unless two highly intractable issues could be resolved: 1) the initial grievances against the brutal minority regime had been successfully addressed; and 2) the Assad regimes’ (father and son) long history of responding to public protest by mass murder of its own people had somehow been erased. The key question is how to remove the specter of those associated with Assad or his family who would invariably be included in a negotiated transition government. Nader Hashemi of the University of Denver suggests that US leadership in the context of the war in Bosnia is a good model: “the United States effectively laid out a political strategy, mobilized the international community, used its military to sort of assure that the different parties were in compliance with the contact group plan … it presided over a war crimes tribunal …” In his view, prosecuting Assad for war crimes is an important step.

Internal Factor: What is done to repair social divisions and sectarianism in Syria

Nader Hashemi (University of Denver) and Murhaf Jouejati (Middle East Institute) observe that the open ethnic and sectarian conflict that we see in Syria today has emerged there only recently – the result of over five years of warfare, war crimes committed by the Alawite-led government, subsequent Sunni reprisals, the rise of ISIL and international meddling. As a result, there is now firmly-rooted sectarian mistrust and conflict in Syria where little had existed before. Other than pushing for inclusive political processes and rapid and equitable humanitarian relief, there is little that the US or Coalition partners will be able do about this in the short to mid-term. As Hashemi says, healing these rifts will be “an immense challenge; it will be a generational challenge; it will take several generations.” On the brighter side, he also allows that in his experience most Syrians “are still proud to be Syrians. They still want to see a cohesive and united country.” While separation into fully autonomous polities is untenable, reconfiguring internal administrative borders to allow for “localized representation” and semi-autonomy among different groups may be a way to manage social divisions peacefully.

Internal Factor: Demographics and a traumatized population

There is a youth bulge in the Syrian population. Add to this that there is a large segment of young, particularly Sunni Syrians who have grown up with traumatic stress, have missed years of schooling so are deficient in basic skills, have only known displacement and many of whom have lost one or both parents in the fighting. There is hardly a more ideal population for extremist recruiters. Murhaf Jouejati (Middle East Institute) calls this “a social recipe for disaster” that he believes in the near future will be manifest in increased crime and terrorist activity. As a consequence, it is important for the future of Syria and the region to assure that children receive education, sustained counseling and mental health services and permanent homes for families and children.

Contributing Authors

Sayigh, Y. (Carnegie Middle East Center), Jouejati, M. (National Defense University), Ma’oz, M. (Hebrew University, Jerusalem), Hashemi, N (Center for Middle East

Studies, Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver), Landis, J. (University of Oklahoma), Korsmo, M. (Lemay Doctrine Center, Air University),

Gharizi, O. (United States Institute of Peace)

Question (R2 QL 11): What major economic, political and security (military) activities does KSA and Iran currently conduct in Bahrain, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen to gain influence? What are KSA and Iran’s ultimate goals behind these activities? What motivates KSA and Iran towards these goals? What future activities might KSA and Iran conduct in Bahrain, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen?

Author | Editor: DeGennaro, P. (TRADOC G-2/G-27).

The geopolitical landscape in this region is vast and complex. History, lands, family, culture and economic resources are closely intertwined. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and Iran in particular are opposing influencers in these neighboring countries and populations. KSA sees itself as the Sunni protector and the legitimate rulers of the Arabian Peninsula while Iran takes the position of Shite protector. Religion is often used to veil outright economic and military operations by both countries quite often through group proxies. Both Iran and KSA have vast oil and gas resources with extreme and autocratic rulers that work tirelessly to shape, influence and dominate the region thereby ensuring primacy, longevity and wealth.

There are distinct differences between the nations. Iran’ has a rich history from the time of the Persian Empire while the Saud family came from a waring tribe in the desert cleverly undermining Western colonizers who aligned with its rival ruling family. Both countries have a population with high literacy, but minimal freedoms, Iran’s being a more progressive population with a larger middle class.

To date, each government continues to try project influence internationally, regionally, and locally through statecraft and, sometimes lethally, through proxy actors within and between states. Below are SMA contributions that identify ways in which KSA and Iran influence Yemen, Bahrain, Lebanon, Iraq and Syria in the cognitive, economic, political and security realms. Each has a dedicated narrative giving reason to justify influence although, it is important to note that the receiving countries and non-state actors are not so easily manipulated. Although they may not have similar political powers, they are by no means without their own abilities and interests.

Contributing Authors

Jeddeloh, L. (The Institutional Strategist Group), Mazaheri, D. (IL Intellaine), Sutherlin, G. (Geographic Services Inc.), Gulmohamad, Z. (University of Sheffield)

Specifying and systematizing how we think about the Gray Zone.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., Polansky (Pagano), S., & Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc).

In their continued work on the changing nature of the threat environment General Votel et al (2016) forecast that the majority of threats to US security interests in coming years will be found in a “gray zone” between acceptable competition and open warfare. They define the gray zone as “characterized by intense political, economic, informational, and military competition more fervent in nature than normal steady-state diplomacy, yet short of conventional war,” (pp. 101). While this characterization is a useful guide, it is general enough that efforts by planners, scholars and analysts to add the level of specificity needed for their tasks can generated considerable variation in how the term is applied, and to which types of actions and settings it applies.

What lies between acceptable competition and conventional war?

Far from an unnecessarily academic or irrelevant question, this is a critical question. How we define a condition or action, in other words the frame through which we are categorizing certain actions as threatening rather than “normal steady-state” impacts what we choose to do about them. The “I know it when I see it” case-by-case determination of gray vs not gray limits identification of gray zone actions to those that have already occurred. Gaining some clarity on the nature of a gray zone challenges is essential for effective security coordination and planning, development of indicators and warning measures, assessments of necessary capabilities and authorities and development of effective deterrent strategies.

The ambiguous nature of the gray zone and the complex and fluid international environment of which it is a part, make it unlikely that there will be unanimous agreement about its definition. Our first goal in this paper then, is to describe the gray zone as much as define it. We begin with a review the work of a number of authors who have written on the nature and characteristics of gray zone challenges, and use these to identify areas of consensus regarding the characteristics of the gray space between steady-state competition and open warfare. We next use these to suggest a more systematic process for characterizing different shades of gray zone challenges.

Question (V4): Post-ISIL Iraq Scenarios. What are the most likely post-lSIL Iraq scenarios with regards to Political, Military, Economic, Social, Information, Infrastructure, Physical Environment, and Time (PMESII-PT)? Where are the main PMESII-PT friction points, which are most acute, and how are they best exploited to accomplish a stable end state favorable to U.S. and coalition interests?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

“The biggest danger is to assume we know the answer.” Alexis Everington, Madison Springfield Inc.

“The unpredictable nature of the country’s social sentiment, lessons from history, the culture, regional influencers, the corrupt political elite with their sectarian-based agendas, and lack of statesmanship and political and strategic prowess are among the factors that suggest that even the most seasoned expert on Iraq might be misled in his or her attempt to predict the next phase.” Hala Abdulla, Marine Corps University

Seventeen experts contributed their thoughts about the future of Iraq and Syria in a post- ISIL environment. Summarizing their insights, warnings, and predictions in under five pages runs the risk of over simplifying and incredibly complex challenge, which is why this summary is heavily cited to encourage the reader to seek further details in the texts provided.

This summary is divided into three parts: 1) a table that describes the PMESII-PT elements essential to understand the current and future trajectory of Iraq and Syria, 2) a brief description of various friction points, the resolution of which may influence the future of the region, and 3) the suggested elements that may encourage the transition to stability.

Friction Points (Including Most Acute)

If the number of grievances listed in the table above are not addressed after the fall of ISIL, the fear is that the region will descend once again into a number of conflicts, including continued extremism (Van den Toorn). This section lists friction points identified by the contributors as fulcrums in the future of Iraq and Syria that could tip the scales toward stability or violence.

The Battle for Mosul

“A victory over ISIL will not be the end of Iraq’s problems, rather the beginning of an internal political battle over territory,” according to CSU professor Ibrahim al-Marashi.

The way the battle for Mosul is conducted, as well as its outcome, may be the greatest determinant of the future of the Middle East (Dagher; Abdulla). If it is done wrong, it could lay the groundwork for the re-emergence of ISIL or a successor group. If it is done right, it could provide a model for integration, governance, and recovery for the region (Dagher). In a comparative study of Mosul vs. Fallujah, Zana Gulmohamad listed three major contributors to successful operations: effective coordination of Iraqi forces, coalition airpower, and intelligence from Sunni tribes and townspeople—even in the face of unauthorized incursions by Shi’a militias.

But there are many dangers along this path. First, one of the greatest fears of the Sunni population is that Shia militias will once again be allowed to dominate Sunni populations under the guise of liberation (Dagher). Second, the new governance structure in Mosul must address political grievances of diverse population groups in Mosul. The government must draw its leadership from a new political elite that is of and from Mosul. The existing sources of political power in Ninewah represent the nexus between Islamist extremists and the organized businesses that thrived during ISIL’s occupation of Mosul and should not be allowed to dominate the regional government. Likewise, the new government should pay close attention to minority groups, to pose a model for integration and representation in the country and the region (Dagher, al-Marashi).

Finally, the battle for Mosul poses risks to the cohesion of the Coalition itself. There are any number of occurrences, described in a report by Allison Astorino-Courtois, NSI, that could cause partial or severe fracture before, during, or after the battle. The longer cohesion is required, the likelihood of a spoiler event increases. Zana Gulmohamad notes that unless conflicting agenda among regional powers can be resolved, any victory in securing the city could be fleeting.

Transformation of ISIL from Proto-state to Insurgent Group

The battle for Mosul may effectively push ISIL out of Iraq and into Syria (Abouaoun). This will likely be the turning point of ISIL from a proto-state to an insurgency group (al Marashi; Abouaoun) with the intent to encourage violence on near and far enemies, especially through the encouragement of lone wolf terrorism. This pressure could also result in jihadists leaving ISIL for other groups or inspire some to create new ones (Abouaoun). The bottom line is that ISIL will decline, but the ideology will not.

Even after ISIL’s defeat, individuals, groups and networks of fighters and terrorists will be motivated to continue violent jihad, whether against local regimes, the West, Shiites, or apostate Sunnis. In a post-Caliphate ISIL, threats will take two main forms, according to David Gompert, a national security expert at the US Naval Academy and RAND: 1)R remnants of fanatical forces in the region, including in Iraq, Syria, and Libya and 2) radicalized individuals in or returning to the West. This former group could lead to increase terrorism in the West.

Federalization of Iraq

There were two major schools of thought regarding the idea that the federalization of Iraq is one way to address popular grievances, governance issues, and mistrust of the central government. Several experts suggested that a federalization model based on Kurdish semi- autonomy might provide a stable way ahead (Maye, McCauley). The arguments in favor of this stance include self-determination, freedom from domination by other ethnic groups, and potential for buy in from Iraqi Sunnis, Shia, and Kurds (McCauley). The primary US role in this effort would be to bring the parties to the table to negotiate and enforce an agreement (McCauley).

However, another cohort of experts argued that constitutional autonomy will not work in Iraq—particular in traditionally Sunni-held areas (Dagher; Abdulla). The people of Iraq all want unity except for the Kurds (Abdulla). Furthermore, Sunni territories in western Iraq are not economically viable (Abdulla). As people tire of sectarian conflict, one way forward may be to support a secular, technocratic party (Maye). However, the success of this kind of party would undermine all existing political actors and is likely to be undermined unless it receives strong international support.

Power Sharing in Syria

The issue is not how Assad should share power in a post-ISIL world, but the fact that he cannot share power without unraveling the entire government (Sayigh). Assad’s goal in Syria is not total victory (because that only allows him to become the king of ashes); his goal is to regain access to capital and markets and get sanctions lifted (Sayigh) (Sayigh). Assad cannot do this with diplomacy, so he is using the conflict to coerce the US, EU, GCC, and Turkey to make economic concessions. Russia and China will endorse this demand as will Lebanon and Jordan in order to ease pressure on their domestic concerns.

Settlement of Intra-group Tensions

The greatest threat to long-term stability in Iraq is not tensions between Sunnis, Shias, and Kurds, but intra-Sunni, intra-Shia, and intra-Kurdish tensions (Abdulla; Liebl). Sunnis lack any kind of unified political voice and efforts to consolidate power may lead to tribal conflict. While the Kurdish government faces significant rivalry between its two main political parties, the KDP and the PUK, for power (Abdulla). However, the real determinant of stability in Iraq hinges on the settlement of Shia-Shia tensions in the country (Sayigh; Abdulla). Although Iraqi Shia present a united façade, there are serious divisions among its main blocs, leaders, and elites (Abdulla). Shia-Shia competition for influence over the Iraqi state could lead to bloodshed (Sayigh).

Environment

Long-standing tensions are often inflamed by disagreement over scarce water resources (Palmer Moloney). This is particularly true in the Tigris-Euphrates Watershed, which is shared by Turkey, Syria, and Iraq and largely controlled by Turkey (Palmer Moloney, Meredith).

Achieving a Stable End State Favorable to US and Coalition Interests

This section briefly lays out suggested actions and conditions to promote a stable end state in Iraq and Syria favorable to US interests in the days after Daesh.

New Regional Framework

The most important action the USG and the Coalition can take to promote stability in the region is to bring all actors to the table to agree on a new regional framework (van den Toorn, Trofino, Abouaoun; Meredith). Iran, Saudi, and neighboring Sunnis states must be encouraged to form a new regional framework. Real stability in the region cannot be accomplished without bringing these actors in general agreement (van den Toorn).

Economic Revitalization of Iraq & Syria

Funds for the reconstruction of Iraq and Syria are essential not only to prevent humanitarian crisis, but to shore up the economic stability of the region. How reconstruction funds are handled could either serve as a foundation for a new transparent and accountable economy system or entrench the population’s perception of government corruption and negligence (van den Toorn).

Focus on Capacity, Autonomy, and Legitimacy

No matter what kind of states emerge from the post-ISIL environment—be they unified states of Iraq and Syria or federalized zone within each country—they all require three things: capacity, autonomy, and legitimacy. The Coalition can take action to support these three elements in a number of ways outlined in Spencer Meredith’s contribution including the encouragement of nationalism and ensuring the reduction of violence.

Be Ready to Take Advantage of Cognitive Openings

Even if groups fight efforts to establish good governance or to lay down arms, there is often a few windows of opportunity to encourage these groups to join the fold (Meredith). These cognitive openings do occur. The USG has to be ready to take advantage of them. The Coalition should be looking for indicators of cognitive opening by conflicting parties through 1) moderated speech, 2) evidence of factional divisions within a group, and 3) failure to claim ownership for violence.

Increased Faith in Iraqi Special Forces

The fight against ISIL has proved that Iraq has at least one reliable force: the US-trained Iraqi Special Forces (ISOF) and Counter Terrorism Forces (ICTF), which includes Iraqis from all ethnic and religious backgrounds (Abdulla). The danger is that a prolonged infantry war for a unit designed for short, special operations might soon experience significant fatigue. But this unit provides a model and hope for what Iraqi forces could look like in an integrated Iraq.

Bilateral Power Engagement

The USG has soft power tools at its disposal to conduct symbolically meaningful engagement with the populations in Iraq and Syria. These tools “carry major weight in the MENA,” according to van den Toorn. The USG could promote education exchanges, business opportunities, and cultural exchanges.

Contributing Authors

Abbas, H. (National Defense University), Abdulla, H. (USMC Center for Advanced Operational Culture), Abouaoun, E. (United States Institute of Peace), Al-Marashi, I. (California State University, San Marcos), Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI), Dagher, M. (Independent Institue for Administration and Civil Society Studies), Everington, A. (Madison Springfield Iinc.), Gartenstein-Ross, D. (Valens Global), Gompert, D. (US Naval Academy, RAND), Gulmohamad, Z. (University of Sheffield), Liebl, V. (Center for Advanced Operational Cultural Learning), McCauley, C. (Bryn Mawr College), Meredith III, S. (National Defense University), Palmer-Moloney, J. (Visual Teaching Technologies), Maye, D. (Embry Riddle Aeronautical University), Sayigh, Y. (Carnegie Middle East Center), van den Toorn, C. (American University of Iraq, Sulaimani)

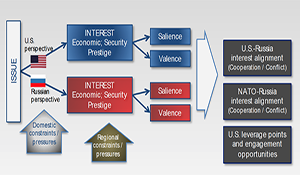

Drivers of Conflict and Convergence in Eurasia in the Next 5-25 Years — Integration Report.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc).

Evaluating strategic risk in the Eurasia region over the next two to three decades is a complex challenge that is vital for USEUCOM planning and mission success. The depth of our understanding of the diverse set of political, economic, and social actors in the region will determine how effectively we respond to emerging opportunities and threats to US interests. A better understanding of Russia’s priorities and interests, and their implications, both regionally and globally, will help planners and policy makers both anticipate and respond to future developments.

The official project request from USEUCOM asks that SMA “identify emerging Russian threats and opportunities in Eurasia (with particular emphasis on EUCOM AOR countries). The study should examine future political, security, societal and economic trends to identify where US interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests, and in particular, identify leverage points when dealing with Russia in a “global context” Additionally, the analysis should consider where North Atlantic Treaty Organization interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests” They also provided a list of questions covering: regional outlook; China; regional balance of power; Russian foreign policy; leadership; internal stability dynamics; media and public opinion; US foreign policy and regional engagement; NATO.

To address these questions, SMA brought together a multidisciplinary team drawn from the USG, think tanks, industry, and universities. The individual teams employed multiple methodological approaches, including strategic analytic simulation, qualitative analyses, and quantitative analyses, to examine these questions and the nature of the future operating environment more generally.

The diverse range of approaches and sources utilized by the individual teams working on the EUCOM project is one of the strengths of the SMA approach; however, it also makes comparison and synthesis across individual reports more challenging. For this reason, NSI developed a structured methodology for integrating and comparing individual project findings and recommendations in a systematic manner.

This report provides an overview of the regional issues identified by the US, Russia, NATO and EU in policy statements, speeches, and the media, and how they intersect with actor interests. It then presents the major themes arising from the integration of the team findings in response to USEUCOM’s question, in particular the importance of understanding Russia’s worldview, and the subsequent recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing the probability of cooperation with Russia.