SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Joint Concept for Human Aspects of Military Operations (JC-HAMO).

Author | Editor: Joint Staff.

The Joint Concept for Human Aspects of Military Operations (JC-HAMO) describes how the Joint Force will enhance operations by impacting the will and influencing the decision making of relevant actors in the environment, shaping their behavior, both active and passive, in a manner that is consistent with U.S. objectives.1 Human aspects are the interactions among humans and between humans and the environment that influence decisions. To be effective at these interactions, the Joint Force must analyze and understand the social, cultural, physical, informational, and psychological elements that influence behavior. Actors perceive these elements over time, mindful of seasons and historical events, and with people having differing notions regarding the passage of time. Relevant actors include individuals, groups, and populations whose behavior has the potential to substantially help or hinder the success of a particular campaign, operation, or tactical action. Relevant actors may include, depending on the particular situation, governments at the national and sub-national levels; state security forces, paramilitary groups, and militias; non-state armed groups; local political, tribal, religious, civil society, media, and business figures; diaspora communities; and global/regional intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations.

Military efforts in the recent past have produced many tactical and operational gains, but rarely achieved desired political objectives and enduring outcomes in an efficient, timely, and effective manner. The elusiveness of success, despite unmatched U.S. conventional combat capabilities, highlights that militarily defeating adversary forces, in and of itself, does not automatically achieve strategic objectives.

Recent failure to translate military gains into strategic success reflects, to some extent, the Joint Force’s tendency to focus primarily on affecting the material capabilities—including hardware and personnel—of adversaries and friends, rather than their will to develop and employ those capabilities. The ability to destroy the material capabilities of adversaries and strengthen those of friends has always been, and will continue to be, critical. However, military operations are most effective when they induce or compel relevant actors to behave in a manner favorable to the United States and its partners.

The human aspects of military operations are critical considerations in traditional and irregular warfare. Thus, JC-HAMO re-focuses the Joint Force on understanding relevant actor motivations and the underpinnings of their will, and developing and executing more effective operations based on these insights. The consideration of the human aspects of military operations is central to various forms of strategic competition and all Joint Force operations. A failure to grasp human aspects can, and often will, result in a prolonged struggle and an inability to achieve strategic goals. With insightful analysis, the Joint Force can identify opportunities for collaboration and discern weaknesses and exploit divisions among adversaries.

Enhancing the Joint Force’s ability to conduct military operations, which have the required impact on the will and decision making of relevant actors, demands a detailed understanding and consideration of the human aspects of military operations. This understanding and consideration is critical during the planning, directing, monitoring, and assessing of operations. It is also vital to the provision of military advice to policymakers. To accomplish these efforts, the JC-HAMO identifies the following four imperatives that are instrumental to inculcating in the Joint Force an updated mindset and approach to operations:

- Identify the range of relevant actors and their associated social, cultural, political, economic, and organizational networks.

- Evaluate relevant actor behavior in context.

- Anticipate relevant actor decision making.

- Influence the will and decisions of relevant actors (“influence” is the act or power to produce a desired outcome on a target audience or entity.

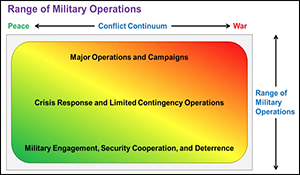

These imperatives apply to all facets of the National Military Strategy and all the primary missions of the U.S. Armed Forces, as outlined in the Defense Strategic Guidance, Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense. These imperatives pertain to the full range of military operations (ROMO) and the entire conflict continuum.

The JC-HAMO mindset and approach, which provides the foundation for a core competency on the human aspects of military operations throughout the Department of Defense (DoD), requires institutional change across the Joint Force.4 Military leaders must understand how to work with partners and decision makers to support the development of political strategies and determine how military operations will contribute to sustainable outcomes consistent with U.S. interests. A renewed focus on the human aspects of military operations is necessary to:

- Develop deep understanding to enable friendly forces’ decisions.

- Effectively articulate purpose, method, and desired state for each operation and campaign—and identify “human objectives” that focus on influencing relevant actors.

- Deter aggression and prevent, mitigate, contain, and win armed conflicts.

- Influence friendly, neutral, and adversary actors to build the strength of the Joint Force and its partners—and gain advantage in the operating environment.

- Provide sound advice to military and civilian leaders with regard to the size and scope of U.S. interventions and make possible, when appropriate, a small-footprint approach that will prevent the overextension of the Joint Force.

- Enable capable partners to assume the lead when and where it is fitting to do so.

A critical objective of the JC-HAMO is to improve decision making and the application of operational art and design by Joint Force members. The goal is not to advocate for a separate line-of-effort or a new occupational specialty dedicated to the human aspects of military operations, although access to regional specialists, social and cultural anthropologists, and other technical experts is important. Rather, the aim is to elevate the performance of the entire Joint Force. As a human aspects core competency takes hold and matures over time, it will generate a broad range of knowledge, skills, and abilities—sustained via a learning continuum—that will enable the Joint Force to improve its strategic competence and aptitude to contribute to the achievement of national policy objectives.

Part IV: Analysis of the Dynamics of Near East Futures: Assessing Actor Interests, Resolve and Capability in 5 of the 8 Regional Conflicts.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

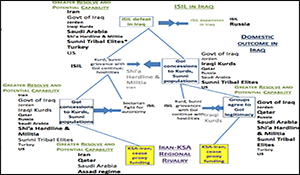

This briefing is the final part of a four-part study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. Part II describes the system and why it is critical to assess U.S. security interests and activities in the context of the entire system rather than just the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the U.S. is most interested. Part II describes the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actor over five of the eight conflicts. Part IV presents the results of the interest, resolve, capability assessment.

Unpacking the Regional Conflict System surrounding Iraq and Syria—Part III: Implications for the Regional Future: Syria Example of Actor Interests, Resolve and Capabilities Analysis.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

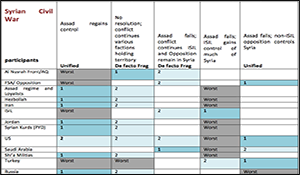

This is Part III of a larger study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. Part I described the system and why it is critical to assess US security interests and activities holistically rather than just in terms of the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the US is most interested. Part II described the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actors for five conflicts. It uses the Syrian Civil War as a use case.

This paper presents the analysis of the Syrian Civil War to illustrate the analytic process that was applied to 20-plus actors over five regional conflicts in and around Syria and Iraq: 1) The Syrian Civil War; 2) the battle to Defeat ISIL in Syria; 3) the battle to Defeat ISIL in Iraq; 4) the Iran-Saudi Regional Rivalry; and, 5) the conflict over domestic control among the Shi’a hardline, Kurds, Abadi Government and Sunni tribal leaders. It looks in detail at the actor interests involved in the Syrian Civil conflict and includes the top-level findings assessment, characterization of the conflict based on the interests at stake, description of the posited outcomes, a summary of the preferences over those outcomes for each participating actor and a discussion of the implication of actor resolve and capabilities.

Examinations of Saudi-Iranian Gray Zone Competition in MENA, and of Potential Outcomes of the Flow of Foreign Fighters to the United States.

Author | Editor: Capps, R., Ellis, D. & Wilkenfeld, J. (ICONS).

Executive Summary

The United States is regularly challenged by the actions of states and non-state actors in the nebulous, confusing, and ambiguous environment known as the Gray Zone. Planners, decision makers, and operators within the national security enterprise need to understand what tools are available for their use in the Gray Zone and how to best develop, employ, and coordinate those tools. This report summarizes the results of simulations created and executed by the ICONS Project as part of a larger study to capture at least some of the information needed toward that end.

On October 24, 26, and 28, 2016, under the guidance of the Pentagon’s Office of Strategic Multi- Layer Assessment and the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of University Programs, staff of the ICONS Project at the University of Maryland executed three simulations. Two of these examined competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia in the Gray Zone, both direct and through proxies. The third examined the threat to the homeland of a collapse of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

Participants in the simulations were drawn from various U.S. government agencies and from universities, research centers, think tanks, foreign governments and militaries. Within each of the three simulations participants were given start states and asked to react to events introduced into the scenario. Broadly, the start states placed the participants in mid-2017, about six months into a new U.S. administration. They were told the USG had placed a priority on understanding and shaping the relationship between Iran and Saudi Arabia (in two of the simulations) or in understanding and protecting the homeland against any threat evolving from the competition between Islamic State and Al Qaida (in the third). Play in each of the simulations took place virtually with participants joining via ICONSnet from around the world. Each of the three simulations ran for four hours.

There were five principal take-aways from these simulations:

- It may not be possible for the U.S. to influence or shape Gray Zone activities by other states, especially when those actions are not directed toward the United States. When two states or a mix of state and non-state actors want to engage in the Gray Zone, there may be little the U.S. can do to stop them. Sometimes the only possible action is no action other than planning for likely results.

- Violent extremist organizations may act in the Gray Zone in an attempt to drag state actors out of the Gray Zone. State actors need to have appropriate strategies developed and responses queued for rapid delivery.

- The U.S. is not the sole major power assessing threats and opportunities in Gray Zone conflicts and competitions. It is possible that actions by other major powers could draw the U.S. further into conflicts or drive parties to violence.

- To operate effectively in the Gray Zone, U.S. policy designers and operators need access to every available tool; a whole-of-government approach is crucial to success. In fact, we should begin to think in terms of a whole-of-government-plus structure where government reaches out to non- government regional and technical specialists, subject matter experts, and other “different thinkers” to formulate courses of action.

- Controllers noted a clear bias among the U.S. government participants toward Saudi Arabia and against Iran, and a willingness to move rapidly to kinetic or other military action by some of the military players. Such an overt bias may adversely affect the ability of the U.S. to take advantage of opportunities for influence in Gray Zone conflicts.

Participants in the Iran-Saudi Arabia simulations stated in after action reviews their belief that the U.S. must recruit, train, and deploy the right people with the right skills, including a mix of government and non-government thinkers. There was also a note that the USG lacked a cabinet level information agency dedicated to developing and disseminating the U.S. narrative and to countering enemy narratives.

In their after-action reviews, participants in the foreign fighter scenario focused on the difficulties of developing and maintaining a common operating picture across federal, state, and local entities; on the importance of understanding the roles, capabilities, and authorities of each entity; on the importance of accurate and timely intelligence, and how to share information to best effect across agencies where security clearance levels vary.

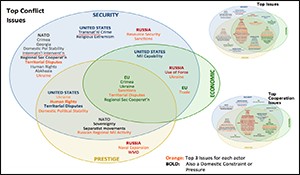

Drivers of Conflict and Convergence in Eurasia in the Next 5-25 Years — Integration Report: Executive Summary.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc).

This project identified threats and opportunities in Eurasia (with particular emphasis on USEUCOM area of responsibility (AOR) countries). This report provides an overview of the regional issues identified by the US, Russia, NATO, and the EU in policy statements, speeches, and the media, and how they intersect with actor interests. It then presents the major themes arising from the integration of the team findings in response to USEUCOM’s questions, in particular the importance of understanding Russia’s worldview, and the subsequent recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing the probability of cooperation with Russia.

Evaluating strategic risk in the Eurasia region over the next two to three decades is a complex challenge that is vital for USEUCOM planning and mission success. The depth of our understanding of the diverse set of political, economic, and social actors in the region will determine how effectively we respond to emerging opportunities and threats to US interests. A better understanding of Russia’s priorities and interests, and their implications, both regionally and globally, will help planners and policy makers both anticipate and respond to future developments.

The official project request from the United States Navy asked that the Strategic Multi:Layer Assessment (SMA) team “identify threats and opportunities in Eurasia (with particular emphasis on USEUCOM area of responsibility (AOR) countries). The study should examine future political, security, societal, and economic trends to identify where US interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests and, in particular, identify leverage points when dealing with Russia in a ‘global context.’ Additionally, the analysis should consider where North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) interests are in cooperation or conflict with Russian interests.”

To address these questions, SMA brought together a multidisciplinary team drawn from the United States Government (USG), think tanks, industry, and universities. The individual teams employed multiple methodological approaches, including strategic analytic simulation, qualitative analyses, and quantitative analyses, to examine these questions and the nature of the future operating environment more generally.

The diverse range of approaches and sources utilized by the individual teams working on the USEUCOM project is one of the strengths of the SMA approach; however, it also makes comparison and synthesis across individual reports more challenging. For this reason, NSI developed a structured methodology for integrating and comparing individual project findings and recommendations in a systematic manner.

This report provides an overview of the regional issues identified by the US, Russia, NATO, and the EU in policy statements, speeches, and the media, and how they intersect with actor interests. It then presents the major themes arising from the integration of the team findings in response to USEUCOM’s questions, in particular the importance of understanding Russia’s worldview, and the subsequent recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing the probability of cooperation with Russia. The report is structured as follows:

- Identifying issues and mapping actor interests in the USEUCOM AOR

- Russia’s worldview

- Regional cooperation and conflict

- Domestic stability and instability in Russia

- Recommendations for reducing conflict and increasing cooperation

Demystifying Gray Zone Conflict: A Typology of Conflict Dyads and Instruments of Power in Libya, 2014‐Present.

Author | Editor: Gabriel, R. & Johns, M. (University of Maryland, START).

This case study is intended to highlight the dynamics of Gray Zone conflict in Libya since 2014. It places specific emphasis on the roles of non‐state actors within the conflict and how these actors utilize different levels of power to achieve their aims. With a focus on analyzing the dyadic relationships between various types of conflict actors, this research examines which types of dyads employ which instruments of power, as well as to what extent these activities fall within the Gray Zone of conflict as opposed to the more precisely delineated Black and White arenas. This research aims to assist practitioners and policy makers in determining how the types of actors involved in a conflict can influence which instruments of power deserve special consideration in that conflict. This investigation will also aid Special Operations Forces (SOF) in determining which types of belligerents may make effective partners depending on the type of adversary faced, and which instruments of power SOF should train and equip these partners to implement.

This research substantially bounds the scope of what needs to be considered by U.S. forces operating in these environments. Specifically, the analysis shows that aggregating by actor‐type is effective. Aggregating Libya’s myriad actors into four distinct groups, which include internationally recognized governing bodies, rival political factions (hereby referred to as “rival governments”), local religiously‐ affiliated violent non‐state actors (VSNAs) and transnational VSNAs (e.g. the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)), allows practitioners to identify the most relevant instruments of power at play given the actor‐types engaged in the conflict. Moreover, this analysis reduces the number of instruments of power that must be thoroughly considered in each conflict dyad from seven to an average of 4.5. Of these 4.5, an average of just 2 instruments of power are especially salient.

Furthermore, this analysis demonstrates that Libya’s conflict is Gray. While Gray Zone dynamics also include White and Black activities, all four of the dyads involve Gray activities. This study finds that competition between the elected and/or internationally recognized governing bodies and rival governments primarily occur across the diplomatic, informational, military, economic, financial and legal instruments of power. The situation in Libya is such that competing political groups have all had periods of international recognition and legitimacy at certain times and not others. During periods where a government has international recognition and legitimacy, it tends to prioritize White Zone diplomatic engagement and legal activities. When rival political groups are not internationally recognized, they have employed Gray Zone diplomatic negotiations, information engagement and financial activity in addition to Black Zone military and economic action.

Religiously affiliated VSNAs (including ISIL and al‐Qaeda (AQ) affiliates) are also involved in the conflict. Notably, information engagement occurring within the Gray Zone is the most potent instrument of power used by such groups regardless of the adversary, followed by Black Zone military action. When competing against government aligned forces, these VSNAs have similarly engaged in Gray Zone financial activity. Local VSNAs have engaged in Gray Zone diplomatic negotiations with international actors. In its competition against government‐aligned forces, ISIL has employed Black Zone economic activities.

When evaluating responses to conflicts involving governments and rival governments, practitioners should devote significant attention to the use of diplomatic and legal instruments of power as they have proven to be especially consequential. When addressing dyads involving religiously‐affiliated VNSAs, practitioners should pay particular attention to the informational and military instruments of power, as these instruments of power influence the use of the other instruments.

While the approach adopted by this research entails myriad advantages, readers should be cautioned that Gray Zone conflicts are extremely complex. Practitioners ought to consider how an intervention against one type of conflict actor might affect other types of actors operating in the same space. This is necessary to avoid negative externalities, such as inadvertently strengthening other combatants. Moreover, commanders must realize that the successful use of certain tactics within one instrument of power (e.g. military), can have profound effects on the efficacy of their opponent’s use of other instruments (e.g. economic or informational). Finally this case provides numerous examples of government forces collaborating with various VSNAs. While Special Operations Forces are especially well positioned to do so, this requires extensive situational awareness at the micro‐level as the micro and macro conflict landscapes are mutually constitutive and are thus highly reactive to disturbances on all levels. Alliances are fleeting and the willingness to cooperate with Special Operations Forces varies both over space and time.

Operating in the Gray Zone: An Alternative Paradigm for U.S. Military Strategy.

Author | Editor: Echevarria II, A. (U.S. Army War College).

Recent events in Ukraine, Syria, Iraq, and the South China Sea continue to take interesting, if not surpris- ing, turns. As a result, many security experts are call- ing for revolutionary measures to address what they wrongly perceive to be a new form of warfare, called “hybrid” or “gray zone” wars, but which is, in fact, an application of classic coercive strategies. These strat- egies, enhanced by evolving technologies, have ex- ploited a number of weaknesses in the West’s security structures.

To remedy one of those weaknesses, namely, the lack of an appropriate planning framework, this monograph suggests a way to re-center the current U.S. campaign-planning paradigm to make it more relevant to contemporary uses of coercive strategies.

Question (R2#12): How does the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict influence, affect, and relate to current conflicts in the region?

Author | Editor: Wilkenfeld, J. (University of Maryland, ICONS).

The Israel-Palestine conflict has been a constant presence in the Middle East since Israel’s independence in 1948. But even earlier in the 20th century, Arabs and Jews were in conflict over competing claims to the same territory. The Balfour Declaration of 1917, which provided a home for the Jewish people in parts of Palestine, along with the Sikes-Picot Agreement of 1916 which divided up the territories formerly ruled by the Ottoman Empire, remain a continuing thorn in the side for Arab states in general, and for Palestinians in particular. It is also true that the rise of Arab nationalism, coupled with the centuries-old Sunni-Shi’a divide, have shaped the perceptions and destinies of Arab leaders and populations.

The critical question is the extent to which these seemingly separate conflicts overlap such that developments in one impact the others. In particular, under what circumstances does the status of the Israel-Palestine conflict today impact the larger conflict dynamics at play in the region? Is Israel- Palestine at the heart of all conflicts in the region, or is it merely a convenient whipping boy and perhaps even a singular unifying factor for populations and states riven by seemingly unrelated competitions for power?

Not surprisingly, then, the subject matter experts we have consulted on this question have expressed a considerable diversity of opinion. Nevertheless, one critical theme has gained traction. For the most part, the SMEs argue that Israel-Palestine has little to do with the broader conflict dynamics that characterize the region today. The quest for greater participatory democracy that typified the Arab Spring movements in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, and Yemen would seem to be unrelated to developments in Israel-Palestine. Similarly, the overarching competition for power in the region between Shi’a and Sunnis, as reflected in the intense competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia, has on the surface little to do with Israel-Palestine. But as all the SMEs observe, Israel-Palestine is invoked at the level of a “sacred value,” in this case a deep-rooted feeling of shame and helplessness that periodically rises to the surface and is invoked either as a scapegoat by failing governments or as an unfulfilled quest by their restless populations. And so even as all dismiss the notion that the Israel- Palestine conflict is the primary driver of all conflict in the region, its invocation as a continuing grievance and as a motivating force must be factored into our own perceptions of these other conflicts and their underlying causes.

And thus, the answer to the Command’s seemingly straightforward question is complex. The circumstances under which Israel-Palestine becomes a central narrative for Arab leaders and their populations with quite diverse local conditions and goals can include these and other factors:

- National leaders seek to divert attention from internal divisions and their inability to address local grievances – economic, social, and political

- Local populations express anger with the US and the West for their historical support for authoritarian regimes through criticism of their role in perpetuating the Israel-Palestine conflict

- Islamist revolutionary movements seek a unifying theme to garner support from local populations through championing the Palestinian narrative

In the following passages, we summarize the key points made by the group of SMEs consulted on this issue. This is followed by their full input, and biographical sketches.

Professor Michael Brecher (Angus Professor of Political Science at McGill University) takes the position that to view the Israel-Palestine conflict as a central driver of all conflict in the Middle East is to ignore dynamic forces of change in the region, particularly increasingly positive relations between Israel and several of its Arab neighbors. This latter trend has the effect of blunting the impact of Israel-Palestine tensions. Even though the relations between these former inter-state adversaries could not move beyond a Cold Peace, their bilateral conflicts and the Arab/Israel Conflict as a whole had begun the process of accommodation and conciliation. The extent of change became clear at the turn of the century (2000), when the Arab states adopted the Arab Peace Initiative, which offered Israel recognition and normal relations with all members of the Arab League, in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from its occupation of Arab territories in 1967 and acceptance of the Palestinians Right of Return, in accordance with the UN 1949 Resolution. Israel did not accept those conditions and the conflict continued. Nonetheless, Israel’s right-wing Prime Minister publicly accepted the ‘two state’ solution to the Israel/Palestine conflict in 2009. Moreover, the Arab League renewed its ‘Peace initiative’ in 2007 and 2014.

General (Ret.) Shlomo Brom (Senior Research Associate at the Tel Aviv University Institute for National Security Studies) argues that while neither the Arab Spring uprisings nor the current Sunni-Sh’ia divide have anything to do with Israel-Palestine, sometimes Israel serves as a convenient card played by these regional powers in their struggles. For example, Iran is using its hostility to Israel as a way to buy influence in Sunni Arab societies. Nevertheless, Arab societies’ frustrations that led to the present chaos in countries like Libya, Yemen, and Syria were fed also by feelings that they were wronged by the Western powers and Israel and the perceived injustice done to the Palestinians are part of these wrongs in the Arab psyche. One can also argue that the Arab authoritarian regimes that are another cause for the present situation fed on the Arab-Israeli conflict and used it to justify their rule and the huge expenditure on security and the armed forces that were the base of their rule.

Professor Aron Shai (Eisenberg Professor for East Asian Affairs Departments of History and East Asian Studies, Tel Aviv University) posits that it is easy to dismiss Israel’s culpability in the larger regional, ideological, and religious conflicts sweeping the region today. But for Israel’s current right wing government, the mere fact that Arab states and extremist movements invoke Israel-Palestine as a basis for struggle, is used as justification for not seriously initiating sincere steps towards peace. Arab and Palestinian views tends to magnify the impact of the conflict and in fact internationalize it. This serves Israel’s interests quite well.

Professor Shibley Telhami (Sadat Chair for Peace and Development, University of Maryland, and Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution) offers the following listing of instances where the Israel-Palestine conflict has been a factor in seemingly unrelated conflicts.

- The social media groups that were critical for the Arab uprisings in 2010 were initially mobilized over the 2008-9 Gaza war between Israel and Hamas

- Opposition groups, including militant Islamists, continue to invoke Palestine centrally in their mobilization efforts

- The verdict is still out on how much stability will come to both Egypt and Jordan, with the opposition in both continuing to invoke Palestine/Israel

- Despite the Arab media focus on the Arab uprisings, especially Syria, once war flared in Gaza again in 2014, Palestine overtook all other stories including Syria

- Despite stable peace agreements between Israel on the one hand and Egypt and Jordan on the other hand, Egyptians and Jordanians continue to reject Israel over its occupation

- While some Arab states in the GCC would like to cooperate even more with Israel over some issues like Iran, they fear a domestic backlash (as happened recently over Saudis who made contacts with Israelis). And the take has been that Israel would make it harder for the Saudis to ask other Muslim nations to take its side against Iran if Israel is seen to be on the Saudis side.

- The Jerusalem issue remains one that resonates across the Muslim world. Crises could bring this to the top.

Contributing Authors

Brecher, M. (Angus Professor of Political Science at McGill University), Brom, S. (Tel Aviv University), Shai, A. (Tel Aviv University), Telhami, S. (University of Maryland & Brookings Institution)

Question (LR4): What is the strategic framework for undermining ISIL’s “Virtual Caliphate?”

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Iran’s Approach in Iraq

Shifting to a Virtual Caliphate

As ISIS loses ground in Syria and Iraq, the organization seems to be evolving to emphasize the information battlefront to both maintain and gain support from sympathetic Sunni Muslims across the globe and open a new front against its far enemies. Research conducted by Dr. Larry Kuznar, NSI, showed a marked shift in Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s and Abu Mohammed al Adnani’s (before his death) speeches in 2016 indicating a shift towards the virtual caliphate. Adnani’s speech first signaled a turn towards virtual caliphate in May 2016. Baghdadi, whose speeches have traditionally focused on the near enemy, signaled a turn toward the virtual caliphate in November 2016 as indicated by more frequent mentions of Libya and Tunisia, decreased mentions of an apocalyptic showdown in Dabiq, and the beginning of the expression of an alternative conceptualization of the caliphate.

Strategies to Undermine the Virtual Caliphate

ISIS has adeptly used social media, information operations, and propaganda to recruit foreign fighters, to encourage skilled individuals to migrate to ISIS-held Iraq and Syria, and to gain sympathy and support. But the Virtual Caliphate implies more than just an impressive command of cyber-based information tools—it sows the irretrievable ideas of violent jihad that will be accessible on the internet for generations, inspiring others long after ISIS has ceased to hold territory. Contributors to this write up suggested a number of ideas that do not easily combine into a seamless strategic framework for undermining the virtual caliphate, but present components for consideration.

Dr. Hassan Abbas, a professor at National Defense University, suggested that the most powerful thing the coalition can do is to support the development of a legitimate, credible Sunni Muslim voice—such as the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC)—to provide a counterweight to ISIS. “For many Muslims, especially those vulnerable to ISIL recruitment, lack of Muslim unity and weak ‘Ummah’ is seen as the biggest challenge,” he argued. Furthermore, Muslim collaboration on a larger scale (e.g., economic, educational, etc.) is likely to be very well received globally, particularly by young Muslims. This would also help counter the narrative that Muslims are weak and have been humiliated by the West, which drives support for ISIS.

Dr. Kuznar suggested five lines of effort that focus on increasing pressure on ISIS as it transitions from the physical to virtual caliphate to reduce its chance of lasting success.

- Continue to defeat ISIS militarily to discredit them and to force them to force a new narrative This report does not represent official USG policy or position. 1

- Continue to target top ISIS leadership, especially ideologues who are responsible for narrative generation

- Work with and enable credible alternative voices in Islamic world that can divert vulnerable recruits away from violent jihadist movements and inspiration

- Beware of alternate jihadists capturing ISIS’s market share of the virtual Caliphate as ISIS is further discredited

- Plan for cooperation with DHS and allies to mitigate persistent effects of lingering ISIS messaging in cyberspace

MAJ Patrick Taylor, 7th Military Information Support Battalion, USASOC, suggested that a new framework for undermining ISIS’s virtual caliphate is not needed. “[W]e do not require new doctrine or a new approach, we must simply apply current doctrine in creative ways as a framework for response. This is a return to first principles,” MAJ Taylor concluded. He argued that Psychological Operations is uniquely positioned to operate in the virtual battlespace using Cyber Enabled Special Warfare (CE-SW). He suggested thinking of the virtual domain as contested borderland filled with neighboring states, tribes, and communities with various competing interests. Successful operations require developing relationships with online digital natives to enable the USG and its allies to compete for functional capability in the information environment. As in other domains, It is essential to understand the viewpoints of these online tribes and communities in order to understand and combat the interests the drive mobilization.

Conclusion

ISIS’s shift from physical to virtual caliphate is extremely dangerous as it is a threat that will continue in perpetuity even after ISIS, the organization, is defeated. Violence seekers will be inspired by ISIS’s hateful rhetoric, other insurgent groups can learn from ISIS’s successes and failures, and the threat of homegrown violence may continue to rise. These conditions are unlikely to change, but we can perhaps limit the scope of the threat by considering some of the suggestions proposed here among others.

Contributing Authors

Abbas, H. (National Defense University), Kuznar, L. (NSI, Inc. and Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Taylor, P. (7th Military Information Support, USASOC

The Conflict in the Donbas between Gray and Black: The Importance of Perspective.

Author | Editor: Finkel, E. (University of Maryland, START).

The current case study analyzes the presence and importance of Gray Zone conflict dynamics and the employment of various instruments of power during the still ongoing conflict in Eastern Ukraine (Donbas) since its beginning in 2014. More specifically, it studies the use of various instruments of power across a number of conflict dyads, present in the conflict. The case study’s findings can better inform practitioners and analysts about the presence, content, and effectiveness of utilizing different instruments of power in the Gray Zone.

The analysis covers the participation of various entities and groups, operating in the Donbas: the governments of two states, Russia and Ukraine; the initially independent volunteer formations on the Ukrainian side; and two quasi-state insurgent entities. The analysis uncovers numerous Gray Zone interactions across several dyads, but also demonstrated the limits of the Gray Zone both as a set of empirical actions and as a conceptual approach to understanding the conflict itself. This study shows that Gray Zone activities exist to varying degrees in all dyads, but they are most pronounced in the Ukrainian versus Russian governments dyad.

In addition to uncovering and analyzing the existing Gray Zone dynamics, the case study also argues that Special Operation Forces should pay substantial attention to preexisting perceptions, media framings and worldviews in devising general Gray Zone policies and actions. Thus, the analysis shows that the classification of the conflict in the Donbas as a Gray Zone conflict is possible only if the emphasis is put on the interactions between the Russian and the Ukrainian governments as the primary driver and cause of the violence. However, if the attention is shifted towards domestic, rather than geopolitical causes of the violence, the conflict is more properly classified as a Black Zone conflict. These differences in classification can have substantial impact on the specific policies and actions, adopted by Special Operations Forces.

The analysis also shows that in practice, Gray Zone dynamics are extremely complicated and involve numerous actors and activities, often operating independently of one another. Based on the analysis of the Russian government’s actions, the report demonstrates the inherent difficulties and limitations of Gray Zone actions, especially under conditions of large scale conflict. The report also shows that Gray Zone activities that utilize some instruments of power can and do operate simultaneously with both Black and White Zone activities that leverage other instruments. This suggests that the Zones are not exclusive across the entire spectrum of instruments. Rather, they are instrument-specific, thus offering Special Operation Forces a wide spectrum of potential actions to choose from.

Finally, the analysis shows that many of the Gray Zone activities, utilized by non-state actors on both sides of the conflict are driven by primarily financial considerations and have a substantial criminal component. Practitioners, devising the application of Gray Zone tactics by non-state actors should be aware of potential implications of Gray Zone activities for law and order.