SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

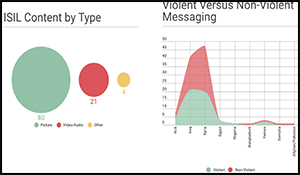

Question (QL5): What are the predominant and secondary means by which both large (macro-globally outside the CJOA, such as European, North African and Arabian Peninsula) and more targeted (micro- such as ISIL-held Iraq) audiences receive ISIL propaganda?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

The contributors to this Quick Look demonstrate clearly the breadth and diversity of the ISIL media and communication juggernaut identifying a wide variety of targeted audiences, media forms and distribution mediums for both local and global audiences.

Smartphones are game-changers; the predominant distribution medium globally and locally

There was general acknowledgement among the experts that wide-spread, public access to smartphones has been both a game-changer for both the distribution and production of propaganda materials. Smart devices with web access were also cited by many as the predominant medium by which both global and local audiences receive ISIL propaganda and the catalyst for the fading of former distinctions between means used to communicate with “macro” versus “micro” audiences. Even ISIL messages primarily intended for local audiences (e.g., weekly newsletters) do not stay local; they are digitized and may be found on the internet and thus are available globally.

Chris Meserole a fellow at the Brookings Institution argues that ISIL communicators have benefitted from two particular capabilities that smart devices put in the hands of users: 1) easy access to impactful video and other visual content has enabled ISIL to transmit highly emotive and pertinent content in near real-time; and 2) users’ ability to produce and distribute their own quality images has altered the processes of recruitment and identity formation by making them more interactive: group members who formerly would have been information consumers only, now can readily add their voices to the group narrative by serving as information producers as well.

Cyber platforms are critical but consider Twitter and YouTube as starting points

Although Twitter, and YouTube are still the most commonly used platforms, and especially Twitter can be used for specifically-targeted, micro audiences, Gina Ligon who leads a research team at the University of Nebraska Omaha cautions that ISIL’s cyber footprint extends well beyond these “conventional” platforms which should be considered “mere starting points for its multi-faceted, complex cyber profile.” (See the Ligon et al below for ranks of the top cyber domains ISIL used between August 2015 and August 2016.)

It is important to note that although there is clearly increased local agency regarding production of ISIL communications, the teams from the University of Nebraska (Ligon et al), UNC-Chapel Hill (Dauber and Robinson) as well as Adam Azoff (Tesla Government) and Jacob Olidort (Washington Institute) find substantial evidence of centralized ISIL strategic control of message content. However, once content is approved, a good argument can be made that dissemination of ISIL messages and even video production is localized and decentralized. The result is a complex and “robust cyber presence.”

Static or moving images – key to evoking emotion — characterize all forms of ISIL propaganda

The most distinctive characteristic of ISIL propaganda is its high quality visual content which are easier to distribute than large texts. It is also easier to evoke emotion with an image than with text. Arguably, the most prolific and widely-distributed propaganda are ISIL’s colorful print and digital magazines (e.g., Dabiq, Rumiyah in English, Constantinople in Turkish Fatihin in Malay, etc.) It is well known that ISIL videos are extremely pervasive and an important form of ISIL messaging. However, multiple experts noted that the sophistication and production value of today’s videos are a far cry from the 2014-era recordings of beheadings that horrified the world.

Not everything is digitized: solely local propaganda forms and mediums

Audiences both in and outside ISIL controlled areas and those outside the region receive ISIL propaganda products. However, there are some mediums and forms of propaganda which can only be delivered in areas in which ISIL maintains strict control of information and in which it can operate more overtly. For example, ISIL has printed ISIL education materials and changed school curricula in its areas, it holds competitions and events to recruit young people, and polices strict adherence to shar’ia law (hisba). It is in this context that Alexis Everington (Madison-Springfield) argues, one of the most impactful forms of ISIL messaging remains its visible actions (of course, the perceived actions of Iraqi government forces, Assad forces, etc. and the US/West are likely equally, if indirectly, impactful). Second in importance are “media engagement centers such as screens depicting ISIL videos as well as mobile media trucks.” Outside ISIL controlled areas, NDU Professor of International Security Studies Hassan Abbas, cites “the word of mouth” including “gossip in traditional tea/food places” as still the primary means by which local audiences receive ISIL propaganda, and many experts agree that the content is “largely influenced by religious leadership.”

What happens next?

Finally, Adam Azoff of Tesla Government offers a caution regarding what happens when ISIL-trained, foreign media operators are pushed out of all ISIL-held areas: as these fighters relocate we should be prepared for the possibility that they would “continue their ‘cyber jihad’ abroad and develop underground media cells to continue messaging their propaganda. Though it will be more difficult to send out as large a volume of high-quality releases, it is not likely that ISIL will return to the amateurish and locally-focused media operations of 2011.”

Contributing Authors

Abbas, H. (National Defense University), Azoff, A. (Tesla Government), Church, S. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Dauber, C. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Derrick, D. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Des Roches, D. (National Defense University), Everington, A. (Madison Springfield Inc.), Gulmohamad, Z. (Sheffield University), Johnson, N. (University of Miami), Ligon, G. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Logan, M. (University of Nebraska Omaha), Meserole, C. (Brookings Institution), Olidort, J. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Robinson, M (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Warner, G. (University of Alabama at Birmingham)

Special Operations Forces Operating Concept – A Whitepaper to Guide Future Special Operations Force Development 1.0.

Author | Editor: U.S. Special Operations Command.

Agility and flexibility are the foundational strengths that allow Special Operations Forces (SOF) to rapidly seize opportunities and adapt to unforeseen requirements and operational challenges. Facing a complex and uncertain future, the Nation expects SOF to apply these strengths to more fully integrate with partners and better identify and develop strategic opportunities to advance and protect US interests.

In an increasingly interconnected world, a broadening array of state and non-state actors employing irregular and hybrid approaches challenge US interests. Identifying activities and intentions of these malign actors within disordered societies and disenfranchised populations is challenging, but not impossible. To achieve this, persistent operations and deep understanding of the human domain will be necessary to identify and influence relevant actors to produce outcomes acceptable to the US.

The risk of not acting, or acting late, can dramatically alter the world landscape, eroding the Nation’s security, influence, and standing while allowing nefarious actors to inflict horrific human catastrophe as demonstrated by ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Limited and reactionary responses are the result of insufficient awareness and understanding of emerging indicators of instability.

SOF will always provide critical capabilities to resolve crises and support major operations. However, SOF’s value to the Nation lies in our global perspective, coupled with the ability to act early with partners to provide a range of options for policy makers. Operating ahead of crisis allows SOF and partners to develop long-term and cost-effective options to prevent or mitigate conflict, providing decision space and strategic options to achieve outcomes favorable to the US.

Question (QL3): What does primary source opinion research tell us about population support for ISIL in ISIL-held Iraq and globally outside the Combined Joint Operation Area (CJOA) (Syria and Iraq)?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Opinion polls conducted by independent outfits in 2015 and 2016 derive the same result: the vast majority of Muslims in the region—both inside and outside of the CJOA—do not support ISIL. In fact, ISIL enjoys very low support as a percent of the population across all countries covered by the surveys included in this compilation. Syria showed the highest level of support (20%) while most Muslim-majority countries fall in the single digits (Mauro, 2015). These low numbers recede further when support is defined as providing active or material support rather than sympathy for the cause (Burson-Marsteller, 2016).

Among those who do support ISIL, the reported reason has less to do with religion or ideology than with social, economic, and governance grievances. However, experts interviewed identified two populations of concern: young men across the Arab world who they believe are showing growing complaisance toward ISIL and the radicalized population in Northern Africa. According to Mark Tessler, survey data suggests that North Africans who support ISIL are more severe in their adherence to ISIL’s extremist ideology and espousal of violence support for ISIL is very low. In the five countries surveyed by the Arab Barometer in spring 2016, it is less than 2% in Jordan, less than 3% in Jordan and Morocco, and slightly higher, in the 8-9% range in Algeria and the Palestinian territories. This is the case both for overall populations and for poorly educated younger men, the primary target of ISIL messaging. (see also, Marcellino et al).

It should be noted however, that being widely seen unfavorably does not mean that ISIL is therefore considered the sole enemy. For example, an IIACS poll conducted in Mosul in December 2015 indicated that 46% of the population believed that coalition airstrikes were the biggest threat to the security of their families compared to 38% who said that ISIL was the greatest threat to their family. The poll suggests that US government is just as unwelcome in CJOA as ISIL.

Contributing Authors

Abbas, H (National Defense University), Aguero, S. (US Army), Cragin, K. (National Defense University), Dagher, M. (IIACS), Everington, A. (Madison Springield Inc.), Bahar Firat, R. (Georgia State University), Gulmohamad, Z. (University of Sheffield), Jamal, A. (Arab Barometer), Kaltenthaler, K. (University of Akron & Case Western Reserve University), McCauley, C. (Bryn Mawr College), McCulloh, I. (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab), Moskalenko, S. (Bryn Mawr College), Revkin, M. (Yale University), Robbins, M. (Arab Barometer), Tessler, M. (Arab Barometer)

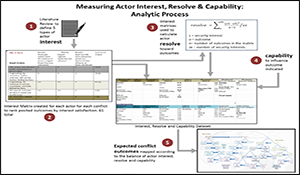

Unpacking the Regional Conflict System surrounding Iraq and Syria—Part II: Method for Assessing the Dynamics of the Conflict System, or, There are no sides—only interests.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

This is Part II of a larger study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. Part I described the system and why it is critical to assess US security interests and activities holistically rather than just in terms of the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the US is most interested. Part II described the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actors for five conflicts. It uses the Syrian Civil War as a use case.

In this region in particular, the absence of warfare does not translate either to stability or to peace. As former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Dempsey suggested in testimony to Congress1, the key question is not how to manage or avoid warfare in the Middle East, but which are the general conditions for peace and stability and what might the US and international community do – or avoid doing – in order to promote those.

What are the dynamics embedded in the region’s current conflicts that will drive it toward one future or another? The outcomes of conflicts are not the result of a single actor’s actions or desires, but are a product of the interactions of opponents; the forces that determine one or another regional future reflect the confluences of actors’ interests, capabilities and resolve. Thus, one way to assess the dynamics that propel the system is to consider three factors that condition the behaviors of state, sub-state and non-state actors:

- Interests — the various security, political, social, economic, and influence interests that an actor perceives to be at stake;

- Capability — the ability to directly influence or cause an outcome to occur; and

- Resolve — the intent or willingness to do so.

The alignment of interests between actors will determine the set of potential outcomes for any particular regional or sub-regional event. However, common interests or alignments between actors may vary across events or conflicts; we cannot assume that a preference for the same outcome in one event will result in shared interests among the same actors in other events. While the alignment of actor interests determines possible outcomes, the distribution of actor resources and resolve across those outcomes governs the likelihood that an outcome will emerge. In other words, the dynamics that determine one or another future reflect the confluences of actors’ interests, resources and resolve.

How stable that outcome is likely to be, however, will be determined not so much by the resources of those who support it, but the resources of those who oppose it. By considering the actors whose interests are blocked or destroyed by a particular outcome, we can also gain insight into the potential durability of a particular outcome. In short, the outcome of a conflict is a function of the interests and preferences of the actors with the greatest resources and resolve relative to that conflict. The durability of that outcome on the other hand, is determined by the resources and resolve of those whose interests remain unfulfilled by the outcome. In shorthand the analytic model is this: Interest + Resolve + Capability = Expectations for the Region.

Risk and Ambiguity in the Gray Zone.

Author | Editor: Wright, N. (University of Birmingham & Carnegie Endowment for International Peace).

Risk and ambiguity are central to activities in the Gray Zone. Policymakers can manipulate risk, and use it as a tool for deterrence or escalation management. They can also manipulate ambiguity. In the Gray Zone understanding risk and ambiguity is key to achieve intended and avoid unintended effects.

(I) What are risk and ambiguity? Defining risk and ambiguity are highly contentious because there are multiple overlapping definitions across different disciplines. This is a classic case of different languages in different disciplines (and in normal language) that can’t be resolved here. However, the basic concepts are not that complicated or confusing.

Here we use a common perspective in economics, psychology and neuroscience. This makes “a distinction between prospects that involve risk and those that involve ambiguity. Risk refers to a situation in which all of the probabilities are known. Ambiguity refers to a situation in which some of the probabilities are unknown”

This maps on to Sec. Def. Rumsfeld’s famous distinction: “Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

(II) Ambiguity in international confrontations: Ambiguity in events and actions gives an extra layer of uncertainty, so they are open to multiple interpretations before we even consider their risk. Cases include: (1) Ambiguity is a key tool in diplomacy. E.g. the 2001 Sino-US crisis where an EP-3 reconnaissance plane force-landed on Hainan Island was resolved by a letter that could be interpreted one way by the Chinese for their public, another by the US for their public. (2) The use of “Little green men” makes an offensive action more ambiguous and so more easily deniable – e.g. at least for observing populations in key allies even if not for US security analysts. (3) How far is a specific action of a local proxy directed by the adversary? (3) Ambiguous thresholds for deterrent threats enable less loss of face if they are crossed, e.g. compared to hard “red lines”. (4) Concessions are critical to managing escalation, and essential when dealing with a nuclear-armed adversary. Ambiguity means they can be offered deniably, e.g. Nixon and Mao. Indeed, clarity too early can prevent later compromise. (5) Economic actions by possible proxies carry ambiguity, e.g. Chinese companies investments on key Pacific Islands. Robert Jervis (1970) includes an excellent chapter on ambiguity, particularly in diplomacy.

(III) Risk in international confrontations: Risk arises when potential outcomes are uncertain, and this pervades all human decision-making. (1) Consider US, UK and German troops currently deploying to NATO’s east, such as the Baltic Republics. Their placement is unambiguous, and provides a tripwire so that there is the risk of escalation if there were serious aggression. This is a classic use of the risk of escalation, as described by Thomas Schelling who devotes a chapter to the “Manipulation of Risk “in his seminal Arms and Influence (1966). Schelling describes how the risk is that escalation can develop its own momentum and this must be managed, e.g. as during the Cuban Missile Crisis. (2) Schelling also argues that “limited war, as a deterrent to continued aggression or as a compellent means of intimidation, often seems to require interpretation … as an action that enhances the risk of a greater war.” – and in the same way, the purpose of entering the gray zone at all can be to manipulate risk. (3) A key distinction from ambiguity is that probabilities are better understood with risk, and thus good baseline data can help turn events from ambiguous to risky.

Options to Facilitate Socio-Political Stability in Syria and Iraq.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc) & Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff).

This White Paper presents the analytic results from Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) project touching on the Middle East and North Africa. The objective is to suggest options to manage conflict in the region and to facilitate socio-political stability in Iraq and Syria. Options that are discussed are intentionally “out-of-the-box”, non-kinetic, and focused on potential Coalition efforts to:

- Diminish the allure of the ideology that Da’esh presents to radicalized and potentially radicalized and other youth in the region; and

- Shape the context to best support reduced regional turmoil and defeat of the Da’esh organization while minimizing the risk of further spread of the jihadist ideology.

The findings are the result of the SMA’s standard multi-disciplinary approach and belief that no single discipline by itself can provide a comprehensive approach to this global and regional conundrum. The analyses were conducted unconstrained by policy, legal, and operational consideration and attempts were made to garner insights from historical precedent.

Following are brief summaries of the articles in this white paper.

In his opening article, Mr. Bob Jones (SOCOM) argues that we live in revolutionary times and ISIL leverages the energy in Sunni populations to their advantage. In revolutionary times, revisionist powers see and seize opportunities; while status quo powers tend to be defensive, reactive, and see agents of change as “threats.” Iran saw an opportunity to expand its sovereign privilege across the region with the fall of Saddam Hussein. Al Qaeda saw opportunity to reduce foreign influence, remove corrupt autocrats, and restore dignity to the Ummah; Da’esh saw the opportunity to best AQ in Syria and Iraq by offering “Caliphate today” in lieu of AQ’s more patient approach.

In his article entitled “Managing the Strategic Context in the Middle East: A Preliminary Transitivity Analysis of the Middle Eastern Alliance Network and Its Operational Implications“, Dr. Larry Kuznar advances balance theory to gauge the overall stability of the conflict system that surrounds the battle against Da’esh in Syria and Iraq. This system is characterized by multiple simultaneous conflicts engaging numerous state and non-state groups in the region and from outside of the region. The analysis focuses on the relations between 24 of the key state and non-state actors in this system and indicates that the region is locked in a well-established system of conflict that is likely to persist given the high degree of transitivity in established relationships.

In “An Analysis of Violent Nonstate Actor Organizational Lethality and Network Co-Evolution in the Middle East and North Africa”, Drs. Victor Asal, Karl Rethemeyer (SUNY Albany) and Dr. Joseph Young (American University) use new data that spans the years 1998 to 2012 to model the behavior of violent non-state actors (VNSAs) in the Middle East. Using several statistical techniques, including network modeling, logit analysis, and hazard modeling, they show that governments can use strategies that influence a group’s level of lethality, their relationships with other groups, and how long and whether these groups become especially lethal.

In his “Countering the Islamic State’s Ideological Appeal”, Dr. Jacob Olidort (Washington Institute) discusses an options-focused assessment for policy and practitioner communities in the United States government concerning the ideological threat posed by the Islamic State. The paper examines the possible evolution of the Islamic State in the event that it loses its strongholds in Iraq and Syria, and the nature of the threat it could pose to Western targets and interests. The assessment is based on the recently-published Washington Institute report, Inside the Caliphate’s Classroom, as well as the author’s cumulative research on the texts and ideas of the Islamic State and other Salafi and Islamist groups.

In their paper entitled “Framework for Influencing Extremist Ideology”, Drs. Bob Elder and Sara Cobb (GMU) discuss negotiation research, drawing on rational choice theory which provides a wealth of findings about how people negotiate successfully. They also describe some of the pitfalls that have been associated with negotiation failures. Building on narrative theory, they attempt to expand the theoretical base of negotiation in an effort to address the meaning making processes that structure negotiation as the basis of a framework for influencing extremist ideology. This research is combined with decision-related research conducted in support of deterrence planning as a means to discover potential influence levers for possible use as a counter to extremist ideology. Recognizing that conflict resolution is complicated because it involves changing the story from within the interactional context from where it arises, the framework assumes a staged approach to address the narrative structure of the ideologically-based conflict which anchors the influence actions on the strategic positions and identities, embedded in the narrative logics of the key characters.

The focus of the article entitled “Off-Ramps for Da’esh Leadership: Preventing Da’esh 2.0”, by Dr. Gina Ligon, University of Nebraska Omaha and Dr. Jason Spitaletta, The John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is two-fold. First, they discuss the underlying theory of TMT (Top Management Team) collaboration, and provide practitioners with some tactics to foment barriers and distrust to aid the operations meant to degrade the organization (e.g., retaking of Mosul). Second, given their analysis of what motivated each of these leaders to join and remain in Da’esh, they provide a set of tailored off-ramps to be considered to deter captured leaders from reconstituting Da’esh 2.0.

In their article entitled “Comprehensive Communications Approach,” (excerpted from their 2016 report, “Examining ISIS Support and Opposition Networks on Twitter,” available at http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1328.html), Drs. Todd Helmus and Elizabeth Bodine- Baron (RAND) argue the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), like no other terrorist organization before, has used Twitter and other social media channels to broadcast its message, inspire followers, and recruit new fighters. Though much less heralded, ISIS opponents have also taken to Twitter to castigate the ISIS message. Their article draws on publicly available Twitter data to examine this ongoing debate about ISIS on Arabic Twitter and to better understand the networks of ISIS supporters and opponents on Twitter in order to craft more effective counter-messaging strategies.

Finally, in “A Human Geography Approach to Degrading ISIL” Dr. Gwyneth Sutherlin (Geographic Services Inc.) argues that stabilizing the region and degrading ISIL will be an international effort with geopolitical and large network engagements. Ultimately, the activities proposed will have an impact for families and their homes on the ground in Syria and Iraq; therefore, the perspectives and priorities of these populations should be foregrounded in any approach, including the involvement of key stakeholders from the earliest possible phase, to lay the groundwork and build partnerships for the long-term stabilization process.

Contributing Authors

Asal, V. (SUNY Albany), Bodine-Baron, E. (RAND), Cobb, S. (George Mason University), Elder, R. (George Mason University), Helmus, T. (RAND), Jones, R. (SOCOM), Kuznar, L. (NSI, Indiana – Purdue U Fort Wayne), Ligon, G. (Univ. of Nebraska Omaha), Olidort, J. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Rethemeyer, K. (SUNY Albany), Spitaletta, J. (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory), Sutherlin, G. (Geographic Services, Inc.), Young, J. (American University)

SMA Reachback Panel Discussion with Experts from Naval Postgraduate School.

Author | Editor: Robinson, G. (Naval Postgraduate School) & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

On 1 November 2016, a team of experts from the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) prepared a two-hour panel discussion based loosely on the first round of CENTCOM¹s reach back questions. The team addressed the following topics:

Topic 1: How the Mosul Campaign Shapes the Future of Iraq

John Arquilla, Chair of the Defense Analysis Department, spoke about how the Mosul campaign will shape the future of Iraq.

Topic 2: Potential of Dispersing Foreign Fighters

Mohammed Hafez, Chair of the National Security Department, is a major contributor to the literature on local Jihadism writ large and discussed the issue of dispersing foreign fighters.

Topic 3: Two Trajectories of a Future ISIS Insurgency in Iraq Post-Mosul

Dr. Craig Whiteside, a professor in the Naval War College, spoke about the two trajectories of a future ISIS insurgency in Iraq post-Mosul.

Topic 4: Lessons from ISIS’s Use of Social Media

Dr. Sean Everton, Co-director of the CORE lab and faculty member of the Defense Analysis Department. Dr. Everton will talk about lessons learned and not learned yet from ISIS’s use of social media.

Topic 5: Thoughts on War-gaming the Coming Instability of a Nation after ISIS

Rob Burks, Senior Lecturer in the Defense Analysis Department of the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) and the Director of NPS’ Wargaming Activity Hub, spoke about wargaming and the potential instability of Iraq after ISIS.

Topic 6: The Future of the Global Jihad after the Loss of the Caliphate

Glenn Robinson, political scientist and on the DA faculty at NPS, spoke about the future of global jihad and the loss of the caliphate.

Contributing Authors

Arquilla, J., Burks, R., Everton, S., Hafez, M., Robinson, G., Whiteside, C., (Naval Postgraduate School)

Question (R3 QL4): What are the critical elements of a continued Coalition presence, following the effective military defeat of Da’esh [in Iraq] that Iran may view as beneficial?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Dr. Omar Al-Shahery of Carnegie Mellon University offers a critical caveat in considering the question posed for this Quick Look. While Iran may see certain “advantages” of the presence of Coalition forces, Iran’s perspective is both relative to the nature of the context and thus transitory as “such benefits might not necessarily outweigh the disadvantages from the Iranian point of view.” If our starting point is that Iran is not happy to have US/ Coalition military forces in the region, then what we are looking for are those Coalition activities that might be seen as minimally acceptable, or “less unacceptable”.

The expert contributors were somewhat divided on whether they believed there were any Coalition elements or activities that they thought Iran might find beneficial. Some believe that there are Coalition activities, primarily related to defeating ISIS, that Iran would find beneficial. Others however do not believe that there is any US military presence in Iraq that would be seen by Iran as sufficiently beneficial to counter the threat that that presence represents. Dr. Anoush Ehteshami, an Iran expert from Durham University, UK, argues that both sides are correct; the difference is whether we are looking at what the majority of experts agree is Iran’s preference, or at Iran’s (present) reality. In other words, it is the ideal versus the real.

However, simply recognizing the ideal versus the real is not sufficient to address the question posed. When the question is essentially what determines the limits of Iran’s tolerance for Coalition activities in Iraq. Context matters. This is because Iran’s perception of political and security threat perception is not based solely on the actions of the West/US, but is the result of (at least) three additional contextual factors: 1) the immediacy of the threat from ISIS or Sunni extremism; 2) the intensity of regional conflict, particularly with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s closest major rival; and, 3) as discussed in SMA Reachback LR2 three-way domestic political maneuvering between Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Rouhani government. This should not be discounted as a key factor in Iran’s tolerance for Coalition presence in the region. The Context can push the fulcrum point such that Coalition activities tolerable under one set of circumstances are not acceptable under others.

The contributors to SMA Reachback LR2 that should be expected to feature in almost any Iranian calculus in the near to mid-term. Relevant to this question these are: 1) expanding Iranian influence in Iraq, Syria, and the region to defeat threats from a pro-US Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Israel and the US; and 2) eliminating the existential threat to Iran and the region’s Shi’a from Sunni extremism.

Iran’s Concerns in Iraq

In general, the experts suggest that from its perspective, Iran’s ideal situation in Iraq would include the following: ISIS is defeated and Sunni extremism is otherwise under control. Iraq is stable and unified with political and security establishments within which Iran has significant, yet understated influence. The ISF are strong enough to maintain internal calm in Iraq, but too weak to pose a military threat to Iran. The strongest Shi’a militia elements are developing into a single Revolutionary Guard Corps type force that is stronger than the ISF. Finally, the major security threats from Israel and Saudi Arabia are minimal and there is no US military presence in Iraq and it is very limited in the rest of the region. This is the scenario that sets the Iranian reference point. All else is a deviation from this.

The Ideal

Iran needs the Coalition for one thing: security. This is security sufficient to defeat ISIS and to stabilize Iraq without posing a threat to Iranian influence. Of course, ISIS, and Sunni extremism more generally has not yet been defeated in Iraq. Iraq is not secure and the Coalition forces have a different perspective on the requirements for a viable Iraqi state (e.g., an inclusive government, a single, unified and non-sectarian security force). The Saudis are irritated, the US remains present in the region, and who knows what Israel is apt to do. According to Iran scholar Dr. Anoush Ehteshami (Durham University, UK), Iranian leaders recognize that they lack the capacity now to defeat ISIS and bring sufficient stability to Iraq to allow for reconstruction. As a result, Iran appears willing to suffer Coalition presence in order to gain ISIS defeat and neutralize Sunni extremism in Iraq – arguably Iran’s most immediate threat. As Dr. Daniel Serwer observes, “for Iran, the Coalition is a good thing so long as it keeps its focus on repressing Da’esh and preventing its resurgence.” Once ISIS is repressed and resurgence checked, the immediate threat recedes (i.e., the context changes) and Iran’s tolerance for Coalition presence and policies in Iraq will likely shift as other interests (e.g., regional influence) become more prominent. The critical question is where the fulcrum point rests, in other words, where is the tipping point at which Coalition presence in Iraq becomes intolerable enough to stimulate Iranian action.

In Reality

In a nutshell, Iran is most likely to find Coalition elements acceptable if they allow Iran to simultaneously 1) eliminate what is sees as an existential security threat from ISIS and Sunni extremism, and 2) expand its influence in Iraq and the region which is a the pillar of its national security approach. Any Coalition element that fails on one of these is unlikely to be tolerated. Put another way, Coalition elements that defeat ISIS but derail Iran’s influence in Iraq will not likely be seen as beneficial. Likewise, as multiple experts point out, Iran is aware that it cannot stabilize Iraq on its own regardless of how much influence it has there.

Contributing Authors

Al-Shahery, O. (Aktis & Carnegie Mellon University), Ford, R. (Middle East Institute); Hamasaeed, S. (US Institute of Peace), Mansour, R. (Chatham House), Maye, D. (Embry Riddle University), Nader, A. (RAND); van den Toorn, C. (American University of Iraq, Sulaimani), Wahab, B. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Meredith, S. (National Defense University), Vatanka, A. (Middle East Institute), Ehteshami, A. (Durham University), Serwer, D. (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies)

Identification of Security Issues and their Importance to Russia, Its Near-abroad and NATO Allies: A Thematic Analysis of Leadership Speeches.

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. & Yager, M. (NSI, Inc).

This study addresses key questions posed in the SMA EUCOM project by using thematic analysis of speeches from leaders of state and non-state polities in Eastern Europe, Russia, and the Caucasus. The importance of an issue is measured by the density (mentions/words in speech) with which it is mentioned and the use of associated emotive language.

Key Findings by EUCOM Questions

Regional Outlook

Q04. Who are Russia’s allies and clients and where is it seeking to extend its influence within the EUCOM AOR?

Analysis of how strongly Russia’s allies express their allegiance to Russia and Russian culture indicates that Crimea is Russia’s staunchest ally. Transnistria also expresses a strong allegiance to Russia, followed by Donetsk. Luhansk and Armenia express pro- Russian sentiments, but only weakly.

Q10. How does Russia see its great power status in the 21st century?

Russian leaders do not mention aspirations for super-power status. Russia’s desire for great power status should be treated as a hypothesis that requires testing – it should not be assumed.

Q20. How might Russia leverage its energy and other economic resources to influence the political environment in Europe and how will this leverage change over the next 15 years?

Economic issues rank high in Russia’s security concerns. They express concern over the value of their energy resources, indicating that it is a key value. They often mention the reliance of European nations on Russian energy. To a lesser extent they mention expanding markets for their energy to Asia.

Media and Public Opinion

Q07. Conduct analysis of open source Russian media to understand key frames and cultural scripts that are likely to frame potential geopolitical attitudes and narratives in the region.

Cultural Frame: A key cultural frame that Russia and its allies use is their history of overcoming odds against aggressive adversaries to uphold their Russian independence. References to the need to defend Russians from the Nazi threat (historically and today) are used. Emotive Frame: Russia sees the US and NATO as a threat, and state that the US is conspiring against them.

Q08. How much does the U.S. image of Russia as the side that “lost” the Cold War create support for more aggressive foreign policy behavior among the Russian people?

Russia and its allies do not speak of losing to the West, but blame past leaders for giving away their power. Some leaders express nostalgia for Soviet power.

Q09. How might ultra-nationalism influence Russia’s foreign policy rhetoric and behavior?

As expected, Russian Nationalists, express nationalist sentiments strongly. However, both Putin and Lavrov use Russian nationalist arguments to some degree.

NATO

Q16. If conflict occurs, will NATO be willing and able to command and control a response?

NATO leaders use language in a manner (mention of security concerns, high emotive content) that indicates a relatively high commitment to addressing Russian threats.

The larger EUCOM effort integrates different teams’ findings in terms of how they relate to security issues, economic issues, domestic constraints, and prestige.

The security issues and themes identified through thematic analysis can be binned under these four interest areas and their densities analyzed. The Putin government exhibits the following patterns:

- Security – The Putin government mentions security concerns more than any other polity; this is related to their engagement in conflicts in the region and to the pervasive threat they perceive the US and NATO to be.

- Economic Factors – The Putin government has one of the highest densities for economic factors indicating that economic interests are a key factor in their decision calculus.

- Domestic Constraints – The Putin government seldom mentions domestic issues.

- Prestige – The Putin government ranks among the lowest of all the polities for the density of prestige-related themes. This is consistent with thematic analysis of the importance of emotive language. Compared to other polities, the Putin government exhibits a cool, measured rhetoric in discussing regional security concerns. This could be a form of deception or evidence of a patient approach to political developments in the region.

Question (QL2): What are the strategic and operational implications of the Turkish Army’s recent intervention in northern Syria for the coalition campaign plan to defeat ISIL? What is the impact of this intervention on the viability of coalition vetted indigenous ground forces, Syrian Defense Forces and Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (formerly ANF)?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

There is general consensus among the expert contributors that the strategic and operational implications of the Turkish incursion are minimal: each sees the incursion as consistent with previous Turkish policy and long-standing interests. Turkey’s activities should be viewed through the lens of its core strategic interest in removing the threat of Kurdish separatism, which at present has been exacerbated by renewed Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) insurgency inside Turkey, its influence in northern Iraq, and the expansion of Kurdish territories in Syria more generally. As one commented, Turkey will prioritize itself. This means preventing the strengthening of Kurds at all costs (including indirect support to those fighting them). It also means patrolling borders, harsh treatment of those who try to get through and/or corrupt practices such as involvement in smuggling. One implication of note however is the increased risk of escalation between Turkey and Russia and Turkey and the US-backed Peoples Protection Units (YPG) that the incursion poses.

Establishing a Turkish zone of influence in northern Syria accommodates multiple Turkish interests simultaneously: from the point of view of the leadership, it should increase domestic support for President Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP); it should allow Turkey to gain control of costly and potentially disruptive refugee flows into Turkey and reduce the threat of ISIL or PKK activities in Turkey; it prohibits establishment of a unified Kurdish territory in northern Syria; and, it secures Turkey’s seat at the table in any Syrian settlement. In addition, a Turkish-controlled zone could establish a staging area from which Syrian Opposition forces could check PYD expansionism, secure the Aleppo corridor and clear ISIL from Turkey’s borders.

In terms of the impact of the intervention on the viability of coalition-vetted ground forces, Alexis Everington (MSI) argues that in order for the campaign against ISIL to succeed in Syria two conditions must be met: 1) that opposition forces in Syria believe that the effort to defeat ISIL goes hand-in-hand with defeat of the Assad regime; and 2) that there are moderate, “victorious” local Sunni opposition fighters that mainstream society can support. If not, the general population is likely to support more extreme alternatives (like Jabhat Fatah al-Sham) simply for lack of viable Sunni alternatives.1 Hamit Bozarslan (EHESS) suggests that unfortunately the ship may have sailed on this condition. He argues that the Free Syrian Army of today, that Turkey backs, has little resemblance to the Free Syrian Army of 2011: many of its components hate the US, are close to radical jihadis and most importantly, in his view are a very weak fighting force. He explains that they succeeded recently in Jarablus because ISIL did not fight (organizing a suicide-attack and destroying four Turkish tanks, simply showed that ISIL could retaliate).

Finally, Bernard Carreau (NDU) argues that “the U.S. should welcome the Turkish incursion into northern Syria and could do so most effectively by reducing its support of the SDF and YPG.” Doing so he believes could make Turkey “the most valuable U.S. ally in Syria and Iraq.” Additionally, the experts suggest that it is important to remember that the Turkish leadership has seen and will continue to see the fight against ISIL through the lens of its impact on Kurdish separatism and terrorism inside Turkey including Kurdish consolidation of power along the Syrian border. The impact on Opposition forces depends on the degree to which they see that the Turkish moves, as well as the campaign against ISIL address their objective of toppling the Assad regime.

Contributing Authors

Natali, D. (National Defense University), Cagaptay, S. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Everington, A. (Madison-Springfield, Inc.), Carreau, B. (National Defense University),Bozarslan, H.(Ecole des Hautes Estudes en Sciences Sociales), Aguero, S. (US Army), Hoffman, M. (Center for American Progress), Sayigh, Y. (Carnegie Middle East Center)