SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Speaker: Warburg, R. (USASOC)

Date: June 2016

COL(Ret) Robert A. Warburg retired on 10/01/2014 after 30 years of service. He is currently the Director, G-9, (Concepts, Experimentation, Science and Technology and Capability Integration and Analysis Directorate’s) at the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC), Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The G-9 Directorate manages the future direction of the command through the Silent Quest Wargame Platform, the USASOC Campaign of Learning Program and the USASOC Futures Forum.

COL(Ret) Warburg served in a variety of leadership positions; from Platoon Leader through Brigade Commander and Army Staff positions ranging from Battalion Operations Officer through Assistant Chief of Staff, G3, of the U.S. Army Special Forces Command (Airborne), headquartered at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He was fortunate to command 1st Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) from 2002-2004.

From 2007 through 2009, he served as the Director of Operations for Special Operations Command – Europe in Stuttgart, Germany. In 06/2009, he assumed command of the 188th Infantry Brigade, part of the First Army Division East, at Fort Stewart, Georgia. COL(Ret) Warburg returned to Fort Bragg in 2011 to serve as the Chief of Staff for the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. From 07/2012 to 06/2014, COL(Ret) Warburg served as the commander of the Military Information Support Operations Command (Airborne), also headquartered at Fort Bragg.

He received the Distinguished Honor Graduate and the William O. Darby Award for U.S. Army Ranger School, Class 05-1992. At his retirement, he received the Distinguished Service Medal from LTG Charles T. Cleveland, the Commanding General of the United States Army Special Operations Command.

Promoting greater stability in post-ISIL Iraq, Volume 2: Why do groups form and why does it matter for stability in Iraq? When the social becomes political.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

United States Central Command (CENTCOM) posed the following question to the Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) virtual reach back cell: What opportunities are there for USCENTCOM to shape a post-ISIL Iraq and regional security environment, promoting greater stability? To address this question, in volume 1, we examine the drivers of legitimacy, security, and social accord for key Iraqi stakeholders. In the current volume 2, we provide an in-depth and comprehensive discussion of the key social elements and dynamics contributing to social accord, and tie the social domain to the political domain in Iraq, with accompanying implications for stability.

Speaker: Monroe, M. (Army University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies)

Date: July 2016

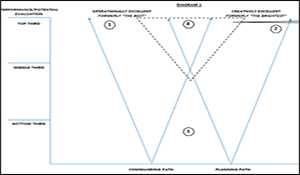

From 03/28 to 06/03/2016, 15 students participated in a nine-week Command and General Staff College Red Teaming elective. In the final exercise the class spent seven days studying gray zone concepts and questions using red teaming methodologies to analyze the concept and offer their insights and recommendations. This paper is the result of their work. The authors promote an alternative approach, which is to adapt officer career and education tracks to create a more operationally and intellectually excellent officer corps. The gray zone is a competition of ideas, and the authors assert that managing the gray zone requires intelligent management of our intellectual capital. The central idea of their alternative approach is to take an internal look to ensure that the Army officer corps maintains a robust educational and institutional base focused on creating a force that can recognize, adapt, and successfully counter the kinds of challenges that gray zone activities present.

Mr. Mark Monroe retired from the Marine Corps in 2009 as a Colonel after 29 years of service. He commanded aviation and artillery units from artillery battery to aviation group-level command, and served at Headquarters Marine Corps, Plans, Policies, and Operations as Readiness Branch Head for the Corps. Mark is a veteran of Desert Shield/Storm, OIF, and several operational deployments. As a naval aviator he held every designation in the UH-1N, and logged 4,200 hours in several type/model aircraft. He served as an instructor at the Marine Corps Weapons and Tactics School, the US Army Command and Staff College, and US Army School of Advanced Military Studies. Mark is a graduate of Oklahoma University, the Naval War College, and the US Army Fellowship program. He currently works with the US Army University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, as a Seminar Leader for Red Team training.

What long-term actions and processes should U.S. government (USG) institutions, the Coalition and the international community examine to position ourselves against a long term ISIL threat? How can the private sector be effectively engaged by government institutions to optimize the effects needed for success?

Executive Summary

Expert contributors agree that terrorism will remain a long-standing global threat. In addition, there is emphasis on the leadership of the USG as a whole of nation concept. The military alone cannot position parties against lasting terrorism threat but it certainly can shape and influence them through stability operations and other people centric maneuvering. It must work in close cooperation with other USG colleagues and coalition partners to do this while mitigating not only ISIL global impact, but other people and groups that strive to commit the devastating acts of violence. Further the USG should take deliberate measures to lessen underlying factors that lead parties to terror responses. Some specific ideas from this group of contributors include:

As war perpetuates and airstrikes continue the USG and its partner’s further loose legitimacy

There already a strong narrative present in the region that the USG instigated the rise of ISIL in order to manipulate governments it did not support and, as necessary, depose them. The USG would be better suited to take its narrative and support it by action. Some examples may include bringing in foreign direct investment that will jump start reconstruction and economic prowess, stabilize Iraqi and Syrian government institutions, and supporting local initiatives that find creative ways to resettle, rebuild and resume ways of life.

Learn to maneuver in the narrative space

It is not a necessity to engage ISIL or other actors on in the social sphere. Simple counter messaging is not going to deter opponents in the battle space. However, it is essential to know what is being said in this space and understanding its impact. Learn the stories and acquire the knowledge about those stories in the historical, cultural, religious and lingual context of the people as a whole. The USG should not take sides, it must operate in site and transparent while working with the host countries to directly solve problems. If people do not feel empowered they will not take ownership, this is how ISIL and others grow. Keep in mind that the narrative space has its threats, but there are also friendly and neutral players that can help the USG show itself under its own narrative of a “moral and democratic” proponent.

Data is your friend

At the CENTCOM reach back center, experts can work with you to streamline real-time data for the warfighter and help enhance decision making and improve the visual battle ground. This is also an area where the military can cooperate directly with the private sector. TRADOC G-27 is increasing improving tools for advanced data and network analysis as it the private sector by researching and looking for partners in the private sector. IBM has introduced Watson, a computer that can complete immense amount of data and information for analysis, visualization, and decision making. Finally, in addition to companies conducting biological and neurological research, some small companies are focusing on sentiment analysis that can support the translation of motivations in populations. For example, one would be able to read popular emotions to see if people support or despise ISIL.

Engaging Academia

The SMA Reach Back effort has shown that the academic community is eager to contribute to national security challenges. CENTCOM can maximize the value of the nation’s intellectual capital by sharing unclassified primary adversary data. This could foster a deep bench of accessible expertise built on empirical, academic studies. Additionally, individuals who straddle the operational/academic divide can be leverages to build an analytic framework that supports systemic evaluation in lieu of ad hoc analysis so often associated with crisis situations.

Everything is local

The ongoing conflict in the region has increased fragmentation in society. There are splits between families, tribes, and religions. Mitigation of ISIL must begin first and foremost at the local level empowering individuals to take charge of their own security and stability. In CENTCOM planning, it will be difficult to do much more than ensure wide area security so the Iraqi government can take the lead to incorporate wayward militias into the Iraqi forces, build strong community policy enforcement, and create space for reconciliation and rebuilding of these fractured nations.

Summary

Taking a realistic view of the expectations of current Arab governments in identifying and alleviating the causes that gave birth to ISIL is essential. It is beyond the existing regimes’ capacities to address the socioeconomic and political conditions of their societies, however, they must be strongly encouraged to do so. To be sure, these regimes can no longer postpone tackling the roots of their citizens’ grievances, which resulted in political violence we see today. In addition, response to these grievances has been brutal leading to injury, jail and death. These collective choices by all governments, for what has been decades, in the region to marginalize or destroy those who do not directly conform or stay silent will plague USG and coalition forces in any long-term defeat of terrorism disseminating from the regions.

It is difficult to see how the above recommendations might be implemented while USG policy in the Middle East policy lacks clarity or cohesiveness. Further the West, most notably the USG, already lacks credibility and what is left continues to dwindle as military maneuvers continue in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. Finally, allowing Israel to also join in their own air campaign deteriorates what is left of USG credibility and the most recent $37 billon US aid package awarded by USG to Israel will no doubt further corrode America’s credibility in the region.

Contributors

Hassan Abbas (NDU), Bernard Carreau (NDU), Patricia DeGennaro (TRADOC G-27), Alexis Everington (IAS), Garry Hare (Fielding Institute), Noureddine Jebnoun (Georgetown Univ.), Spencer Meredith (NDU), Christine M. van den Toorn (IRIS), Todd Veazie (NCTC), Kevin Woods (IDA), Amy Zalman (SNI)

Unpacking the Regional Conflict System surrounding Iraq and Syria—Part I: Characterizing the System.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

This is Part I of a larger study exploring the dynamics of the central Middle East conflict system. It describes the system and why it is critical to assess U.S. security interests and activities in the context of the entire system rather than just the conflicts (e.g., defeat of ISIL) in which the U.S. is most interested. Part II describes the analytic approach used to assess regional dynamics and regional futures based on the alignments and conflicts among three critical drivers: actor interests, resources and resolves. Part III illustrates the analytic process applied to 20-plus actor over five of the eight conflicts. The final results are presented in a Power Point briefing.

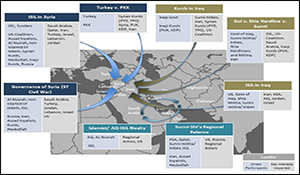

The nature of “the” conflict, or: Why there are no sides

At the beginning of U.S. involvement in the war against ISIL, many U.S. analysts and planners tended to treat the defeat of ISIL as two issues: defeating ISIL in Syria and defeating ISIL in Iraq. There are good reasons for the initial focus on Iraq, including the more significant U.S. interests, relations and sunk costs. As ISIL’s territorial gains progressed, however, the situation became more commonly viewed as a single, cross-border conflict. The reason the conflict engulfing Syria and Iraq is so difficult to grasp is that what many view as one or two conflicts is in reality a complex web of at least eight distinct militarized disputes happening simultaneously in pretty much the same space.1 While some of the conflicts have overlapping participants, possible outcomes, and similar interests, none of the eight are the same on all counts.

We misdirect ourselves if we insist on looking for a consistent alignment of actors – “sides” – across this complex, overlapping and multi-tiered system. Because the same actor can have different widely interests at stake in different conflicts we cannot assume a priori that co-participants like Hezbollah and the U.S. who share preferences over certain outcomes (e.g., the defeat of ISIL in Syria) in one or more of the conflicts will share objectives in the others. Analysis of the actors interests that shape events in the region shows actors can sometimes agree on which is the worst outcome in a given dispute, while being in serious disagreement over which is the best outcome in that same dispute. For example, in the Syrian Civil War Jaish al Fatah and the Assad regime agree that ISIL should not be allowed to expand the self- proclaimed Caliphate over large areas of Syrian territory; however they disagree intensely over who should govern Syria. The reverse can also be true: Turkey, the U.S. and the non-Islamist Syrian opposition might agree that the best outcome in the Syrian Civil War would be replacing the regime with leaders from the non-Islamist Syrian opposition; because they have different arrays of core interests there is less agreement over whether the worse outcome would be the fall of the regime accompanied by ISIL expansion, or, Assad’s regaining control in Syria.

Why is this important? First, coming to grips with these differences – what we might think of as the limits or tipping points of cooperation between actors – is critical for estimating what other actors may do in response to changing conditions in the region. Second, failure to appreciate and manage the broader context within which our counter-ISIL efforts occur leaves us vulnerable to missteps and strategic surprise simply because we have not considered the impact of our actions beyond the battle against ISIL. In fact, looking more broadly highlights a number of scenarios in which the defeat of ISIL, for example accomplished by further alienating the Sunni minority from any political system in Iraq, or by tipping the balance in Iran-Saudi power politics, would actually do more damage to our counter- terror efforts than not having done so.

The remainder of Part I outlines the core issues for eight militarized disputes in the conflict system. To demonstrate what we may fail to recognize about the broader threats to US interests we consider the impact of the total defeat of ISIL in Syria and Iraq on the regional conflict system.

The Power to Coerce: Countering Adversaries Without Going to War

Speaker: The Honorable David C. Gompert (Naval Academy, RAND)

Date: July 2016

The Honorable David C. Gompert is currently Distinguished Visiting Professor at the United States Naval Academy, Senior Fellow of the RAND Corporation, and member of several boards of directors.

Mr. Gompert was Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence from 2009 to 2010. During 2010, he served as Acting Director of National Intelligence, in which capacity he provided strategic oversight of the U.S. Intelligence Community and acted as the President’s chief intelligence advisor.

Prior to service as Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence, Mr. Gompert was a Senior Fellow at the RAND Corporation, from 2004 to 2009. Before that he was Distinguished Research Professor at the Center for Technology and National Security Policy, National Defense University. From 2003 to 2004, Mr. Gompert served as the Senior Advisor for National Security and Defense, Coalition Provisional Authority, Iraq. He has been on the faculty of the RAND Pardee Graduate School, the United States Naval Academy, the National Defense University, and Virginia Commonwealth University.

Mr. Gompert served as President of RAND Europe from 2000 to 2003, during which period he was on the RAND Europe Executive Board and Chairman of RAND Europe-UK. He was Vice President of RAND and Director of the National Defense Research Institute from 1993 to 2000.

From 1990 to 1993, Mr. Gompert served as Special Assistant to President George H. W. Bush and Senior Director for Europe and Eurasia on the National Security Council staff. He has held a number of positions at the State Department, including Deputy to the Under Secretary for Political Affairs (1982-83), Deputy Assistant Secretary for European Affairs (1981-82), Deputy Director of the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs (1977-81), and Special Assistant to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (1973-75).

Mr. Gompert worked in the private sector from 1983-1990. At Unisys (1989-90), he was President of the Systems Management Group and Vice President for Strategic Planning and Corporate Development. At AT&T (1983-89), he was Vice President, Civil Sales and Programs, and Director of International Market Planning.

Mr. Gompert has published extensively on international affairs, national security, and information technology. His books (authored or co-authored) include Blinders, Blunders, and Wars: What America and China Can Learn; Sea Power and American Interests in the Western Pacific; The Paradox of Power: Sino-American Strategic Restraint in an Age of Vulnerability; Underkill: Capabilities for Military Operations amid Populations; War by Other Means: Building Complete and Balanced Capabilities for Counterinsurgency; BattleWise: Achieving Time-Information Superiority in Networked Warfare; Nuclear Weapons and World Politics (ed.); America and Europe: A Partnership for a new Era (ed.); Right Makes Might: Freedom and Power in the Information Age; Mind the Gap: A Transatlantic Revolution in Military Affairs.

Mr. Gompert is a member of the American Academy of Diplomacy and the Council on Foreign Relations, a trustee of Hopkins House Academy, chairman of the board of Global Integrated Security (USA), Inc., a director of Global National Defense and Security Systems, Inc., a director of Bristow Group, Inc., a member of the Advisory Board of the Naval Academy Center for Cyber Security Studies, and chairman of the Advisory Board of the Institute for the Study of Early Childhood Education. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering from the U. S. Naval Academy and a Master of Public Affairs degree from the Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. He and his wife, Cynthia, live in Virginia and Maine.

Promoting greater stability in post-ISIL Iraq, Volume 1: Analysis of the drivers of legitimacy, security, and social accord

for key Iraqi stakeholders.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc.)

Executive Summary

United States Central Command (CENTCOM) posed the following question to the Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) virtual reach back cell: What opportunities are there for USCENTCOM to shape a post-ISIL Iraq and regional security environment, promoting greater stability? Analyses of the security challenges facing post-ISIL Iraq frequently emphasize two central points. The first of these is that any security solution must address the political concerns and goals of key actors. This report is focused on providing insight into not only security factors, but also those political and social factors that have follow-on effects for the security domain. The second point is that both political interests and security interests are highly localized. We acknowledge the tremendous variation in interest groups within the social and political landscape in Iraq. At the same time, social science methodologies are oriented around making sense of such fragmentation, by looking for commonalities within and across societies. While no generalization will ever cover every possible case or variation, the common themes that are derived will represent likely scenarios. Toward this goal, we focus here on the broad ethno-sectarian divisions that are often currently in use in Iraq: Sunni, Shia, and Kurd. Where possible, we seek to specify relevant subgroups (e.g., Shia-led militia, Peshmerga, Sunni tribal elites). While we recognize that there is variation both within and even entirely outside of these groups, the discussion and insights here capture the interests and grievances of a wide segment of the Iraqi population as a whole.

The provision of security is one of the fundamental functions of all governments, and as such, contributes directly to governing legitimacy. For a country such as Iraq, emerging from a period of conflict with unresolved and highly salient sectarian divisions, the relationship between security and governing legitimacy is even more critical for stability. If key stakeholders do not perceive the national government to be legitimate, they are unlikely to trust that that government will meet their security needs. A post-ISIL Iraq will face a complex security environment with multiple government and militia forces identifying with Shia, Kurdish, and Sunni populations as much as, and in some cases more than, with the Iraqi state. Given the recent history of sectarian competition and conflict surrounding Iraq’s security apparatus and national government, political reconciliation between Kurds, Shia, and Sunni, irrespective of the institutional form that takes, will be essential for creating short term stability (ending open conflict). Moreover, the achievement of a more general social accord is a necessary condition for the development of a cohesive national identity. Common national identity (not to be confused with nationalism) increases the legitimacy of national government, and as such, is an important foundation for longer-term political stability.

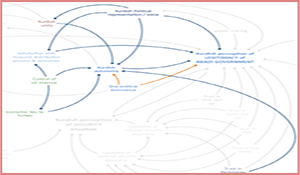

This report presents insights from the analysis of a set of qualitative loop diagrams1 of the security dynamics for Kurds, Shia, and Sunni, constructed around social accord and governing legitimacy in Iraq. The relationships and feedback loops for each of the key stakeholders (Shia, Kurd, and Sunni) have been developed through the application of NSI’s StaM model.2 Our analysis for this report focuses specifically on the dynamics that drive the security and stability challenges facing Iraq post-ISIL. Our analysis indicates that, for each group, there is a key interest—both driving and driven by their relations with other groups—that is central to understanding how the security-legitimacy relationship manifests for that group. For the Sunni, it is their perception of equality (or lack thereof) and fear of retribution; for the Shia, their drive to maintain political dominance, and for the Kurds, their desire for greater autonomy.

A qualitative loop diagram is a visual heuristic for grasping complex recursive relationships among factors, and is a useful means of uncovering unanticipated or non-intuitive interaction effects embedded in complex environments such as that we see in Iraq. It is intended to serve as a “thinking tool” for analysts, practitioners, and decision makers. Once produced, the “map” of the direct and indirect relationships between legitimacy, social accord, and Iraqi perceptions of security, can be used to explore those relationships, test hypotheses about them, and provide a broad picture of second- and third-order effects on critical nodes in the system. For CENTCOM and others involved in building stability in Iraq, a clear understanding of the system that links Iraqi politics and social relations to security is a critical prerequisite for identifying areas in which CENTCOM activities might have the greatest positive impact and those where the risk of unintended consequences is highest.

The report is organized in two volumes: Volume 1, here, presents the detailed insights of the loop diagram analyses, along with a discussion of key areas of opportunity or risk mitigation for CENTCOM, while Volume 2 provides a more in-depth and comprehensive discussion of the key social factors that significantly impact the political domain, and thus ultimately, stability in Iraq. Traditionally, the social scientific emphasis when examining issues of security has been heavily rooted in international relations and politics. In more recent years, additional layers of insight have been added from anthropology, sociology, and psychology. Here, we take a heavily social psychological approach to examining the social domain, though we continue to incorporate concepts from across the social science disciplinary spectrum. The utility of this work is enhanced by the loop diagram methodology—which emphasizes looking at cross-cutting effects both within and across the major domains of interest—and generates new insights about the reciprocal and balancing effects that exist among these social, political, and security domains. This enables a more transparent assessment of relationships both between and within specific groups.

Before turning to the loop diagrams, however, a brief discussion of the concepts of social accord and legitimacy in the context of Iraq is warranted. This is followed by a discussion of important features and nodes excerpted from the complete loop diagrams for Kurds, Shia, and Sunni.3 The final section presents general findings across the various subgroups, and identifies risks and opportunities associated with CENTCOM and other US efforts to shape the security environment and promote stability in post-ISIL Iraq.

Holistic Engagement Activities Ranking Tool (HEART) — A Multi-criteria decision tool to assist in planning and tracking steady state security assistance and engagement activities.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc).

More than ever, United States Government (USG) activities are planned and implemented in an atmosphere of shrinking budgets, high expectations and intense scrutiny at home, plus non-conventional enemies and complex operating environments abroad. In the security realm, there is little debate that the demand for cost-effective, high-impact, and transparent use of government resources requires the Department of Defense (DOD), Department of State (DoS), and other government entities that operate oversees to work together or in complementary ways. Still, departments and their components have their own expanding missions, dwindling resources and programs to administer, making achieving unity of effort difficult. At present, there is no readily accessible process or framework that can incorporate and integrate the range of USG security-related activities abroad and that DOD planners and non-DOD practitioners might use to build common operating pictures – either within their own departments or in coordination with other departments working related activities. This deficiency increases the likelihood that what might be cost-saving efficiencies or wasteful redundancies in US security assistance and engagement programs will go unnoticed by planners and decision makers. Recognizing that US Africa Command (AFRICOM) engagement strategists and planners are in particular need of a systematic process for aligning resources and activities to strategies in the most effective and efficient ways possible, the Command J5 requested that the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) team, “develop an evaluative tool to aid in prioritization and metric development for command engagement strategies.”

Aligning resources to strategy has become an imperative for AFRICOM J5, and other command staffs. However, without a framework and standard measurement schema it is difficult, if not impossible to calculate the relative value of different engagement activities, as well as the trade-offs involved in changing priorities and activities. To address this need, NSI developed the Holistic Engagement Activities Ranking Tool (HEART), an evaluative tool, to provide planners with an accessible means of analyzing and optimizing AFRICOM engagement resources to national and Command objectives while retaining the flexibility to monitor and adjust to rapid changes in political-military environments and/or the priorities (e.g., cost, impact, contribution to mission success, risk to personnel) of greatest concern to the Command.

Countering Violent Extremism: Scientific Methods and Strategies (2015 Edition)

Author | Editor: Fenstermacher, L. (Air Force Research Laboratory)

[Note: 2011 edition available here]

Why are we reissuing the paper collection, “Countering Violent Extremism: Scientific Methods and Strategies”? The answer is simple. Five years later, violent extremism is still an issue. In September 2014, President Obama spoke at the United Nations, calling on member nations to do more to address violent extremism. This was followed by a three-day summit in February 2015 to bring together local, federal, and international leaders to discuss approaches to counter violent extremism. The wisdom contained in this paper collection is more relevant than ever. I encourage everyone to read it, again or for the first time, in whole or in part.

If there were a simple solution for countering violent extremism, a solution would have been found centuries ago. Countering violent extremism successfully requires a balanced approach between security-related strategies and initiatives and those that address the underlying motivations and causes for participation in, and support of, a violent extremist organization (VEO). These strategies and initiatives need to be based on nuanced understanding of the various aspects of violent extremism—not only the environments that are likely to spawn violent extremism and sympathetic supporters, but also

- the types of grievances that predispose those individuals to join and support violent extremist organizations and how they are framed in local contexts;

- the ways in which ideologies, media, messages, and narratives are used to instigate/radicalize, mobilize, indoctrinate, inform, or de-radicalize;

- the social dynamics, capabilities, and resources of organizations that are violent or that are likely to become violent and their relationship with competitors (for attention, resources, etc.); and

- the underlying motivations of individuals (whether revenge, status, identity or thrill seeking1) who join violent extremist organizations.

No single solution or solution set generalizes to all groups or locations, necessitating continuous acquisition of information and updating/adaptation of assessments and strategies.

This paper collection, entitled, “Countering Violent Extremism: A Multi-disciplinary Perspective,” aims to provide new insights on the spectrum of solutions for countering violent extremism, drawing from current social science research as well as from expert knowledge on salient topics (e.g., development programs, cultivating community partners and leaders, conflict and de-radicalization). So what is new? There is a large body of literature on terrorism and violent extremism, much of which focuses on developing a better understanding of the problem, including environmental and social/cultural factors and the role of ideology. This paper collection focuses less on root causes and more on solutions for risk management, disengagement (including delegitimization), and prevention of violent extremism. It also tackles the thorny issue of state terror, a subject that must enter any discussion of solutions for countering violent extremism. Ultimately, it is hoped that the paper collection can inform a better understanding of, and suggest sets of solutions for, motivating individuals and groups to desist from violence and preventing other individuals and groups from seeking involvement in movements/groups that seek to bring about change through violence.

Throughout the collection, there is an undercurrent of “do no harm”; that is, concomitant with suggestions for stopping or preventing violent extremisms, there are cautions an errors to avoid. These cautions implicitly ask the reader to think about things in a different way, in a way that avoids mirroring and simplistic assumptions of what others think or value and widens the timeframe in which we measure success or failure. Many goals related to countering violent extremism, especially disengagement/risk management and prevention require patience and a commitment for the long haul Patience is required to cultivate the right partners, support the building of institutional capacity and development of leaders, fund appropriate development programs to address local grievances, and support and amplify existing programs that support moderate discourse or develop new programs to deradicalize or disengage individuals from beliefs or attitudes. Likewise, messaging must match actions and must stem from someone who is credible and has a thorough understanding of the key ideological, political, and socio-cultural issues as well as the language, narratives, and symbols.

Some of the viewpoints in the collection are surprising and challenge popular conceptions. For example, in some cases, countering violent extremism requires doing nothing; well, not nothing exactly, but rather supporting/amplifying from behind (e.g., supporting social movements seeking governance change) or supporting other leaders, organizations, or states in leading initiatives. A prime example of this is the events of the Arab Spring, which yielded the inherent lesson that, in regions with social injustice and governance grievances , and political opportunity, social movements can and will emerge that motivate change virtually on their own. Another example where a supporting role is often called for is in implementing delegitimization strategies. Delegitimization involves the initiation of a discourse questioning the legitimacy of the violent extremist organization including their performance in other assumed roles/functions (e.g., shadow government, rule of law). This questioning is often best done by others who are more credible, knowledgeable, and steeped in history, ideology, narratives, and culture.

The Crown Prosecution Service defines violent extremism as the “demonstration of unacceptable behavior by using any means or medium to express views which foment, justify or glorify terrorist violence in furtherance of particular beliefs”2 including those who provoke violence (terrorist or criminal) based on ideological, political, or religious beliefs and foster hatred that leads to violence. Thus, countering violent extremism is something that must address instigators; however, first, countering violent extremism involves understanding and countering the ideas that leverage emotions, narratives, and ideologies that impel violence. Countering violent extremism is not the same thing as countering an ideology. This is not to say that ideology is not important or can be ignored. Current research points to ideology as a framing device or tool to rationalize or impel actions. Some believe that a group ideology is effectively an appliqué on top of an ideology, using the ideology for reinforcement and justification or, said another way, “religion and questions of identity (are) interwoven with questions of resources and political economy.”3 Success requires decoupling religious and political ideologies and acknowledging and addressing aspects that can foster the behavior changes we ultimately seek.

- This collection of papers yielded several insights. It is best to seek a balance between reflexive (security based) and reflective (addressing grievances, motivations) actions. Right now, solutions are overly focused on reflexive actions and thus actually create more of the problem we are trying to solve.

- Violent extremist organizations are effectively systems; thus, solution sets must contain tailored (kinetic and/or influence related) solutions for each system component (foot soldiers, instigators, leaders, supporters, logisticians, etc.) in ways that are appropriate for the culture, language, locality/region, and underlying motivations.

- Decision makers should avoid missing the “forest for the trees” by overly focusing on ideology. Local grievances trump global issues and need to be understood and addressed.

- Messengers are only effective when perceived as credible and knowledgeable; simply, if you are not credible, you should not be the messenger. Messages stick when they resonate with grievances, motivate behavior when they provoke affect, and persuade when the actions of the messenger match the words. Our adversaries understand this and employ this understanding in their messaging; thus, our counter messaging should take a “page from the same book.”

- Partners, chosen wisely, are critical in countering violent extremism with, in many cases, our partners in the lead. Without ownership, solutions will not be as successful or lasting,

- Many good things (messaging in Arab popular culture, music, grassroots de-radicalization efforts), are already going on to counter violent extremism around the globe. Success, in many cases, will come from amplifying and supporting what is already working,

- Focus on small, achievable wins over the long haul (e.g., disengagement or risk management versus de-radicalization, delegitimization of strategic objectives or outcomes).

- Delegitimization can be effective in exploiting vulnerabilities and inconsistencies (e.g., disconnects between the fantasy of violent extremism and the reality).

- Our timeframe for countering violent extremism needs to lengthen and the resources for strategies whose payoff is not immediate (e.g., development) must increase. Success will come with sustained efforts with appropriate partners, resources, and (adaptive) strategies.

The collection is organized in four sections, each of which contains papers that provide a tomography for violent extremism, highlighting factors that engender violent extremism and highlighting some of the options of the spectrum of solutions from prevention to changing the (violent) behaviors of already radicalized individuals or groups. The first section provides perspectives on factors and processes underlying violent extremisms and motivates the development of multi-layered tailored strategies. The second section focuses on the prevention of violent extremism: who is at-risk, what is important to many vulnerable populations, who should we partner with, and a variety of proposed solutions. The third section addresses solutions for affecting support for violent extremism, including delegitimization and support or amplification of existing programs (popular culture and music). Finally, the fourth section provides insights on solutions and attributes for solutions whose objective is changing the behavior and/or attitude of violent extremists including de-radicalization/disengagement, deterrence, and coercion.

NSI Chapters:

- Not All Radicals are the Same: Implications for Counter-Radicalization Strategy (T. Rieger)

Contributing Authors

Alahdad, Z. (independent), Belarouci, L. (l’Université d’Amiens), Benard, C. (RAND), Braddock, C. (Pennsylvania State University), Casebeer, W. (US Air Force, Joint Warfare Analysi Center), Corman, S. (Arizona State University), Davis, P. (RAND), DeRouen, K. (University of Alabama), DiEuliis, D. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Policy & Planning), Early, E. (Air University), Farooq, M. (World Organization for Resource Development and Education), Gupta, D. (San Diego State University), Hamid, T. (Potomac Institute for Policy Studies), Horgan, J. (Pennsylvania State University), Huda, Q. (United States Institute of Peace), Larson, E. (RAND), Lemieux, A. (Emory Unversity, START), Mirahmadi, H. (World Organization for Resource Development and Education), Nill, R. (Department of Homeland Security), Speckhard, A. (Georgetown University Medical Center, American College of Greece), Pospieszna, P. (University of Konstanz), Rieger, T. (Gallup Consulting), Sageman, M. (Foreign Policy Research Institute), Shanahan, J. (Joint Staff), Thomas, T. (Office of the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff), Vidino, L. (Center for Security Studies, ETH Zurich)

9th Annual SMA Conference: No War/No Peace…A New Paradigm in International Relations and a New Normal?

Author | Editor: Canna, S., Popp, G. & Yager, M. (NSI, Inc).

Background

Since the end of the Cold War and with the advent of the new century, new geopolitical realities have emerged that have made classical wars with national military forces pitted against each other far less likely. What we are witnessing are new categories of conflict that cannot be considered full1scale wars in the classical sense but cannot be described as “peace” either. Small1scale conflicts are complemented with intense engagement in the Information and other Spheres. These will almost certainly have great implications in the legal domains as well new forms of alliances. Multiple factors have come into play for these trends to emerge. This is a story of change versus continuity, and the conference focused on what has changed since the collapse of the USSR. As such, there are structural and intellectual challenges that prevent the United States Government (USG) from adapting and thriving is this new environment.

Such blurring of war and peace is directly related to the softening of previously considered “solid” categorical binary distinctions (state/non1state, criminal/noncriminal, licit/illicit, etc.). Much of our diplomatic, legal, and military affairs have been predicated on being to able draw clear distinctions between these categories, and many actors are realizing that blurring them provides “strategic ambiguity.” Many of the issues associated with the blurring of these categories are most obvious in the cyber realm. Many of our adversaries are much better than we are at dealing with and, indeed, exploiting these fluid situations.

There are several factors contributing to the issue of “blurring of war and peace.” These include changes to the

- type of actors involved characterized by the blurring of state/non1state, licit/illicit, organized crime/militant actions, etc.;

- intent of those actors (i.e., actors’ willingness to exploit ambiguity);

- capabilities/means that make ambiguous action more viable (e.g., cyber, media operations, the use of proxies, etc.); and

- changes to the strategic context of international political1security dynamics, which will foster and enable such approaches.

Some of these concepts have been around for many decades like Military Operations Other Than War, but there are some fundamental differences that require very different framing and structure, and we simply have not gotten our heads around it as a nation. Government control of information is fading, which has given rise to the global citizen phenomena and globalized what were once geographically bounded, nationalist movements. Even terrorism is globalizing. We read headlines, discuss, and face things today that just did not exist 40 years ago…but our structures to cope were built 70 years ago. We are structured for regime change, to fight nations, and now, by proxy, “groups,” but we have not got a clue how to defeat “movements” that do not possess the familiar nation1state center of gravity and, increasingly, that is what we will face. This all speaks to the limits of power as the sources, derivation, and locus of power is being completely reinvented. The question is do we need a new plan to orient ourselves to face these challenges?

The intent of the conference was to examine the root causes of these new types of conflicts and their implications and provide a contextual understanding. The emphasis was predominantly on the diagnosing of the underlying causes, about orientation, and getting to a meaningful articulation of the problem. In so doing, the conference emphasized and highlighted the need for a “whole1of1government” approach to facing and coming to grips with these challenges. These include military power, diplomacy, and criminal justice, etc. The Panels ranged from those with holistic understanding of these trends to others with a regional focus.

Strategic Multi1Layer Assessment (SMA) provides planning support to Commands with complex operational imperatives requiring multi1agency, multi1disciplinary solutions that are NOT within core Service/Agency competency. Solutions and participants are sought across USG and beyond. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff and executed by ASD (EC P).

Executive Summary

This executive summary highlights key insights derived from speaker and participant interactions. This summary is meant to be comprehensive but does not force consensus. In fact, this summary should highlight that there is a high degree of ambiguity regarding what the gray zone is, what the USG should do about it, and what key questions remain.

The gray zone seems to be a return to an older, more expansive view of how an actor pursues its interests on the international scene. Yet, it only seems “gray” or “new” to us because we have defined a black and white lens through which to see the world. Others clearly do not feel they get value from adopting a similar black and white lens and act in ways that transgress our starker worldview.

Our tendency to think about the world in terms of black and white originates from our success in constructing a world system after World War II that conformed to our values and preferences, making us perfectly adapted to that initial state1base system of global order. As each technological advance concentrated power in fewer and fewer actors, the USG established its hegemony in the international system.% Then the USG created the cyber domain, and it had the opposite effect. It empowered individuals everywhere.

What is our goal in the gray zone?

Conference participants seemed to agree that the US goals with regard to the gray zone should push the USG “left of boom.” The goal is to identify and mitigate threats before they erupt into militarize conflict. Staying in phase zero is victory.

Conference participants spoke about the gray zone in a number of ways. Understanding how we talk about the gray zone will have implications for the conclusions you draw about it. The word cloud below highlights predominant words conference participants used to describe the gray zone during the conference.

Participants nearly all agreed that gray zone challenges take place primarily in the human domain. However, there were two schools of thought regarding the concentration of power. One school of thought felt that state power (as employed by Russia and China) are resurging in news sorts of ways in the gray zone. Both Russia and China have seen the rise of strong, autocratic leaders such as Putin and Xi. The other school of thought acknowledged that while some strongmen remain, in general, power is fragmenting as individuals are empowered. Proponents of the second school of thought argued that the problem with the concentration of power idea is that it correlates wealth concentration with power concentration, which is the exception not the norm in this environment.

Regardless, we seem to be seeing the breakdown of global institutional order, which has changed the distribution of power. This is complicated by the fact that our adversaries now have access to tools and weapons systems previously reserved for states, especially with regard to cyber, drones, and miniaturization. Furthermore, adversaries and competitors will not be constrained by artificial boundaries like the law, bureaucracy, authorities, etc. They operate seamlessly and make decisions quickly.

The gray zone has been alternating and described as an operating environment, a type of conflict, and a strategy. Some felt it exists outside (left of) of the conflict spectrum, some felt it primarily took place in phase zero, and some felt it occurs across the full range of conflict. If you look for opportunities within the gray zone, you realize that the area right of boom is the domain of threats and military conflict, the area left of boom is the domain of opportunity. This domain includes acceptable, if not preferable, competition that we take in order to protect our national interests. The USG clearly sees the gray zone as a threatening, but we should not discount opportunities as well.