SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

SMA Megacities: Deep Dive Application of two socio-cultural frameworks to a flood event in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B,, Brickman, D., Canna, S. & Desjardins, A. (NSI, Inc).

The Strategic-Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Megacity Reconnaissance, Surveillance, and Intelligence (M- RSI) project seeks to aid United States Pacific Command (USPACOM) in understanding socio-cultural dynamics within megacities. For this portion of the project, USPACOM socio-cultural analysis (SCA) planning frameworks (“the SCA approach”) were used to guide remote data collection for a proto-type assessment of the risk of humanitarian crisis in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The SCA approach consists of five distinct, yet related frameworks1 that are designed to provide planners with a quick triage tool to assess risk, as well as provide a guide for analysts conducting longer-term assessments. The five frameworks are structured to reflect USPACOM’s mission objectives and planning process. Given this was a proof of concept effort, analysts were asked to apply two of the five SCA frameworks—the SCA Humanitarian Crisis (HC) Framework and the Intra-state Violence (IV) Framework—to Dhaka, Bangladesh.

In addition to identifying the key risk factors for humanitarian crisis in Dhaka, this study considered the following question regarding the connection between a humanitarian crisis and the risk of intrastate violence/VEO activity in Dhaka:

- Could government/NGO failures to provide immediate relief and rescue in the event of a humanitarian crisis in Dhaka enhance support for VEO-affiliated groups in the city?

The effort represents an initial attempt to expand the use of the SCA frameworks by linking risks in one framework to risks in another as well as determining relationships between, and joint impacts of, framework elements.

During non-crisis (Phase 0) periods, the SCA Humanitarian Crisis framework described below can be used to help analysts and planners track the general nature of the risk of humanitarian crisis. As shown in Figure 1, humanitarian crises can be triggered by one of a number of factors—some environmental (floods) and some socio-political (conflict). All create a unique set of risks for those affected and those seeking to respond. The level and type of risk of humanitarian crisis is determined by the level of services (law enforcement, health and medical, and utilities) the government provides, the readiness and response capabilities, and the recovery capacity of the affected area.

Utilizing data and information remotely collected—to include quantitative and qualitative data, academic research, news reports, and international and NGO policy documents and reports—analysts were able to conduct a quick triage risk assessment of the area of interest, in this case of Dhaka, Bangladesh. For example, they were able to determine how the quality of roads in Dhaka (route trafficability) affected the risk of humanitarian crisis in the event of a natural hazard such as a flood. Analysts employed a simple five-point qualitative coding scheme ranging from no appreciable risk to severe risk to quickly measure risk factors. Roll-up to higher levels was accomplished by applying a simple ordinal measure to these assessments. The “no appreciable risk” elements were scored as 1 (color coded green); low risk of failure as 2 (color coded yellow); moderate risk as 3 (color coded orange); severe risk as 4 (color coded red); and elements that had insufficient information to evaluate were scored as 0 (color coded grey).

Analysts began with a triage assessment of the overall humanitarian crisis factors before delving into analysis of risk in the context of severe flooding. The HC Framework contains factors relating to three stages of disaster relief: immediate impact, disaster response and responsibilities, and recovery and reconstruction. It was important to separate these phases/functions as the information on even the same elements (e.g., actors, procedures, and risk conditions) differs for each. Conducting a deep dive on a single factor allowed analysts to tailor the information related to each element in the risk framework to a specific condition and thus produce more tactical and operational analyses. For example, how flooding may impact the risk of humanitarian crisis due to the flood effects on potable water or delivery of medical supplies to areas in need. Upon completing analysis of the risk of flood-driven humanitarian crisis in Dhaka, analysts conducted a preliminary assessment of how such conditions may increase the risk of intrastate violence emerging as the result of such a flood.

Chapter Two provides an overview of Dhaka as well as a quick holistic assessment guided by the SCA HC Framework of individual factors relevant to assessing the risks of humanitarian crisis. Chapters Three through Five contain detailed assessment of a subset of framework risk factors of importance in the context of a flood in terms of immediate impact, institutional plans and responsibilities, and recovery. Chapter Six discusses how these risk factors relate to, and impact, the IV Framework as applied to Dhaka. Chapter Seven discusses implications for USPACOM and Chapter Eight provides a short discussion on the importance and unique challenges associated with megacities.

Stability Model Users' Guide: Incorporating StaM Analysis of Nigeria for Illustration.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., Brickman, D., Desjardins, A., Popp, G. & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc).

Over the past decade the United States Government has recognized the importance of obtaining a rich contextual understanding of the operating environment, specifically focusing on the human terrain element, when addressing the current threats facing United States security interests, at home and abroad. This emphasis reflects a desire to obtain insight into the motivations underlying others’ intended or actual participation in violence against the United States, as well as the engagement strategies and initiatives that would be effective and sustainable within a given area of interest (AOI). However, this shift in thinking requires analysts and planners to quickly develop a nuanced understanding of the AOIs in which they are working in order to systematically assess their overall stability and identify areas of strength and weakness. A holistic understanding of the operating environment makes it possible to identify critical points in the system – both for stability and instability – and target engagement strategies and initiatives accordingly. This assessment also examines not only the first-order effects, but also potential second- and third-order effects, of US actions across multiple dimensions (governing, economic, and social).,

StaM Overview

NSI’s Stability Model (StaM) represents both a conceptual framework and an analytic methodology to guide users through a systematic process of obtaining a rich contextual understanding of the operating environment. The StaM aids users not only in identifying the factors that explain the stability or instability of a nationTstate, region, or other area of interest, but also in making the connections between and among the various stability factors apparent—allowing users to derive all implications of a potential engagement strategy. The StaM methodology involves an iterative process of “tailoring” or customizing the generic framework to a specific geographic or political area of interest. The output of a StaM effort includes identification of immediate and longerTterm buffers to political, economic, and social stability and sources of population resilience, as well as immediate and longerTterm drivers of instability and collapse. Once a tailored StaM has been prepared, it can be used to address further questions; these include questions regarding the impact of external actors or the most effective and stabilityTpromoting means of engaging with the AOI., , The generic StaM framework consolidates political, economic, and social peer-reviewed quantitative and qualitative scholarship into a single stability model based on these three dimensions, and, critically, specifies the relationships among them. As such, the StaM represents a cross-dimension summary, which draws on rich traditions of theory and research on stability and instability from diverse fields, including anthropology, political science and international relations, social psychology, sociology, and economics. Five key assumptions, shown in Table 1 below, serve as the foundation of the generic StaM.

StaM Assumptions

- A1: Political, economic, and social stability are necessary, but not sufficient, to explain or predict the durability (overall stability) of a political system.

- A2: A governing system will be stable if it is perceived by its constituents to meet their needs (i.e., provides material or nonBmaterial “goods”) and expectations.

- A3: Constituent needs and expectations are culturally and contextually dependent and adaptive.

- A4: The primary “goods” expected from a governing authority are the provision of internal order and external security sufficient for people to meet their physical and psychological needs.

- A5: People do not seek to change systems from which they benefit. Dissatisfaction with the provision of goods by a governing authority reduces the perceived legitimacy of and encourages opposition to that entity.

The overall stability of an AOI—which can be defined within the StaM as either a nation-state, sub-state region, or city—is defined as a compound function of its political, economic, and social stability. Note that the StaM is agnostic to form of governance. Democratic governance is not presumed. It is also agnostic to the type of economic system, and typically will include formal, grey (or informal), and black economic elements. Finally, within the StaM, neither overall stability nor social stability suggest violence- or unrest-free societies, but those where social structures are known and durable, and social cleavages and conflicts are for the most part manageable. Furthermore, stability does not imply a lack of change. Rather, it denotes the flexibility and resilience of a system to adapt to changes over time, without economic, social, or political consequences that threaten the viability of the system.

Analytic Uses of the StaM

Identifying AOI-specific stability conditions

A fully tailored StaM provides analysts and planners with a holistic picture of the governing, economic and social conditions within a specific AOI, and whether that AOI is moving toward or away from conditions consistent with stability in both the short and longer term. It also enables the identification of AOI-specific drivers of instability, buffers to stability and the exogenous conditions that can intensify these effects. Tailoring a StaM requires systematically considering all of the central concepts theory and research have shown effect stability; following the model process allows the planner or analyst confidence that significant current or future sources of stability or instability have not been overlooked.

Monitoring and early warning

Once a tailored StaM has been created for an AOI, and the drivers, buffers and intensifiers identified, the analyst or planner effectively understands what components of the model to pay attention to. This can significantly decrease the time and data requirements for monitoring an AOI over time. Furthermore, as the StaM also maps the crosscutting effects model components have on each other, we can monitor how changes in other components of the model may influence the condition of individual drivers and buffers. This increases the probability that changes with the potential to significantly increase or decrease stability will be identified early in their development.

Assessing the second and third order effects of engagement activities

One of the strengths of the StaM as an analytic tool is its ability to map the interrelationships between model components (crosscutting effects). This makes it possible for analysts and planners to trace the possible consequences of a proposed action and identify possible unintended consequences prior to undertaking an engagement activity. In effect, the model allows users to gain the “lessons learned” without having to make the mistakes that teach the lesson. More importantly, perhaps, the model enables planners and analysts to identify the location and causes of those negative effects. If identified in advance it is possible that such obstacles can be avoided and unintended consequences minimized.

Maximizing the effectiveness of engagement activities

The same crosscutting effects in the StaM that enable the identification of unintended consequences can also be used to determine how engagement activities can be structured and positioned to maximize their effect. By tracing the crosscutting effects from the component that is directly influenced by an engagement action, the planner or analyst can determine the system-wide implications of a specifically targeted action. By comparing different points or methods of influence, the relative impact of various COAs can be compared. In effect, you can determine where you get the most “bang for your buck”.

Improving coordination across USG agencies and international partners

In many cases more than one USG agency may be operating in an AOI, this creates opportunities for coordination, but also risks of duplication or even counteraction of effort. By assessing the second and third order effects of all USG efforts in a particular AOI, the planner or analyst can identify the areas where coordination of effort is most critical. Such an assessment can also bring to light opportunities where interagency collaboration allow individual agencies to achieve mission objectives in areas that they cannot influence effectively working alone. This also holds for working with international partners.

Assessing the implications of external actor actions

It can often be the case that the U.S. is operating in an AOI in which other external actors – either states or non-state actors – are present. The actions of these external actors have potential to impact the stability of the AOI. The StaM allows analysts and planners to map the effects of specific external actor actions (e.g.: presence of VEOs, large-scale economic investment by a foreign power) on the stability of the system as a whole. This in turn can provide a fuller picture of the possible implications of those actions for U.S. interests broadly, and ongoing or planned engagement activities more specifically.

Assessing the second and third order effects of shocks to the system

An AOI-tailored StaM can also be used to assess the likely indirect effects of a particular system shock or crisis event (e.g.: natural disaster, global financial crisis, major terrorist attack). The immediate effects of the shock (for example displacement of populations, crop destruction and infrastructure damage after a natural disaster) can be located on the StaM and then their second and third order effects mapped across the model. Identification of these effects prior to a shock occurring can improve planning and response.

The Dynamics of Israeli and Palestinian Security Requirements in the West Bank—Cross-border activities, sovereignty and governing legitimacy.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A., Bragg, B. & Key, K. (NSI, Inc).

This report presents insights from an analysis of a conceptual map, or qualitative loop diagram that relates Israeli and PA sovereignty and legitimacy in the West Bank territories with Palestinian violence and cross-border attacks against Israeli citizens, as well as IDF/COGAT activities. The relationships and feedback loops of Israeli and Palestinian security and political positions reflect those dynamics that drive the security challenges and risks that impact the effectiveness of PA security sector reform and institutional development. Specifically, the loop analyses suggest that:

PASF capability enhancements can reduce PA legitimacy and limit the effectiveness of security sector reform. PASF capability enhancements seen to also improve security for Israelis can degrade popular support for the PASF, increase social frustration and worsen the security situation in the West Bank. They can also reduce PA legitimacy and reduce the effectiveness of successful security sector reform and institutional capacity building.

Implications for USSC/USG

PASF training/routine emphasizes protection of Palestinians. PASF capability enhancements and training geared toward providing publically observable protection for Palestinians especially in areas associated with Palestinian livelihoods (e.g., orchards) and other areas traversed by Israeli settlers;

Emphasize PASF protection role. Together with visible reemphasis of PASF activities, public affairs communications including outreach to civil society to reinforce message that purpose of PASF is to protect Palestinians can enhance public regard and PA legitimacy;

Emphasize service provision and inclusiveness to enhance PA legitimacy. Other activities to strengthen PA governing legitimacy (e.g., inclusion of alternative views, dependable provision of services) are essential for PA legitimacy and ultimate success of security sector institution building.

Israeli security activities have self-reinforcing adverse effects on PA legitimacy and development of security sector institutions. IDF activity in Areas A and B impact perceived PA governing legitimacy in two ways. Most immediately, IDF security actions, targeted killings, arrests and imprisonment represent an affront to Palestinian national sensitivities and thereby increase the level of social tension in the West Bank. Together with demonstrating the failure of the PA to provide the most basic public service, i.e., security for its citizens, they can diminish popular perceptions of PA legitimacy. Because effective implementation of security sector reforms and institution building require Palestinians to see the PA as legitimate and the PASF as credible, IDF activities also indirectly degrade efforts to build PASF capacity and ultimately to provide security services for Palestinians which feeds into one of the central challenges to the stability of the Fatah-led PA government: the popular appeal and credibility of its phased, institution-building approach versus the approach of Hamas and other actors that highlights rejection and resistance. Completing the feedback loop, impeding the PASF capacity to provide effective security to Palestinians and Israelis in Areas A and B does nothing to reduce Israeli security concerns and reinforces the same, or rising, level of IDF activity in those areas.

Implications for USSC/USG

Advocating for return to more restrictive IDF ROE in the WB including restrictions on live fire, roadblocks and training exercises along with visible reduction in IDF presence in Areas A & B can reduce Palestinian social tension and, if representing observable change can help stabilize day- to-day security situation.

Uncertainty about the final status of the West Bank makes re-opening peace talks more difficult. Uncertainty about the permanence of the current setting in the WB generates two means of decreased WB security. On the one hand it is a direct source of the type of Palestinian social frustration that can lead to violence. On the other, it is a driver of the Israeli government’s accelerated settlement and military establishment construction and consequent illegal seizure and/or destruction of Palestinian land by the Israeli government. This in turn poses an affront to Palestinian notions of national identity, rights and sovereign control, also feeding social frustration and diminishing the popularly perceived governing legitimacy of the PA. Perceived failures of the PA also strengthen the appeal of resistance-based approaches as the only means for dealing with Israel. Given that PA governing legitimacy is so indelibly tied to the phased, institution-building approach established by the Oslo process and the promise of eventual Palestinian statehood (i.e., sovereignty) it significantly weakens any claim to PA governing legitimacy. Unfortunately, it is the PA with which Israel and the US are committed to negotiate a final status agreement and the loss of popular support for the PA coupled with insecure conditions in the Palestinian territories have been used by Israeli leaders as reasons for pulling out of or even engaging in peace talks.

Implications for USSC/USG

US policy supporting “independent, viable and contiguous Palestinian state” has led Israeli governments to create ‘facts on the ground’ and literal barriers to negotiated settlement via land confiscation and military and settlement construction. To Palestinians, US statements, together with settlement construction, can ring hollow or at best are confusing given the intimation of sovereignty associated with “statehood.”

The Science of Decision Making Across the Span of Human Activity.

Author | Editor: Wright, N. (University of Birmingham & Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) & Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc).

The US is affected by the decisions of highly diverse actors, ranging from individuals, to groups (e.g. Violent Extremist Organizations; VEOs) to large and sophisticated states. The behavior of actors at any of these levels can seem “irrational” or “incomprehensible” and thus difficult to deter or influence. Understanding seemingly incomprehensible decision making is even more crucial given the growing centrality of hybrid warfare to the challenges US planners face.

Decisions are made in context and, except for the most extreme (either dire or trivial), they bear on the multiple concerns, preferences and interests a decision maker may have. The choice problems that prompt decisions are comprised of three elements: 1) the options for action an actor believes he/she has; 2) the dimensions (concerns, interests) that determine his preferences over those options; and 3) what he believes other relevant actors will do (i.e., the options and preferences attributed to others, in some cases including the state of nature.) The range of outcomes and actor expected is determined by combining his own options with what he expects others to do. In general, the difference between decision models based on strict rationality assumptions (i.e., rational choice, game theoretic approaches, expected utilty/cost benefit analyses) and those that relax or eliminate these assumptions lies in their suppositions about the nature of the processes by which multi- dimension choice problems are solved and the factors that impinge upon those processes.

Decision Making and Deterrence

Deterring unfavorable actions either by an adversary or a friend is an issue of perception; it has to do with our ability to influence how others construct their choice problems. From a decision-making perspective then, successful deterrence requires the power to alter another’s perception of the demands associated with achieving his objectives to the degree that he chooses to forego actions he would otherwise take. It is important to note that even decision approaches that include “non-rational” factors such as a decision maker’s affective state, health problems, or fatigue, still rely on assumptions about basic human or group behavior. Namely, that their actions are purposeful and that people seek to avoid self-injury or harm however they may define it. Grasping a potential adversary’s understanding of what is injurious or harmful, the interests that impinge on a choice of action, the constraints imbedded in that choice problem, and the process by which it is solved are the critical information requirements for planning to deter terror attacks, regional conflict, nuclear proliferation and even weaponization of space.

US planners and decision makers will require sophisticated analyses related to each of these factors to evaluate how deterrence messages and signals are likely to be received by adversaries and even which alternative, less unfavorable adversary behaviors might be encouraged. They will need the same types of understanding regarding ally decision making in order to send the most effective messages regarding US resolve to extend our deterrent capabilities to their shores.

A final note involves something very often overlooked in US deterrence planning: understanding the political, bureaucratic and social preferences and obligations that condition our own choice problems and decisions. This helps us better appreciate and plan against those circumstances in which we may be self-deterred, and when our own choice processes pose barriers to effective implementation of deterrence messaging or actions.

The Science of Decision Making across the Span of Human Activity

The types of hybrid conflicts that appear to have become the “new normal” in global affairs require equally hybrid response including deterring decisions being made by individuals, groups and states operating simultaneously (e.g. in Ukraine) in various parts of the globe. Taken together the chapters that comprise this volume describe how seemingly incomprehensible decisions made at different levels of analysis most often arise from the predictable ways that individuals, groups and states function. This is a first step in generating the sophisticated understanding of deterrence decisions.

In Chapter 1 Nick Wright draws from neuroscience research to explain adversary behaviors in terms of brain functions and behavioral responses. This predicts different responses to threats intended to deter adversaries versus threats intended to compel other behaviors – and when identical threats provoke attack. He also points out how easy it is to misinterpret an adversary’s activities and response to our own activities simply by our failure to consider the impacts of perceived unfairness.

In Chapter 2 Peter Suedfeld describes the conceptual progress of less dynamic to more dynamic decision theories and models. He presents his cognitive managerial model to help explain how cognitive factors and decision processing at the individual level are conditioned by the nature of the circumstance that the decision maker finds himself at the time of decision.

Clark McCauley moves the discussion to the level of group decision making in Chapter 3. He explains why group decisions are more than just the sum of individual choices. He presents an evolved group dynamics theory to explain how the type of attractiveness that defines the group can result in either: hyper consensual and often premature choice (groupthink); or can polarize the group beyond where its individuals members would have gone alone (e.g. with implications for radicalization).

In Chapter 4 David Gompert, Hans Binnendijk and Bonny Lin discuss twelve cases of war and peace decision making by national leaders and the role that the leaders’ cognitive models and personality traits play in marking the difference between what have been seen as state-level blunders and national security successes.

In Chapter 5 Gina Ligon and Douglas Derrick point out that there are decision dimensions included in VEO decision making that are unique to those types of organizations, including for example, the need for increasing violence both for reasons of organizational credibility and to maintain public attention. VEO decisions can appear to be incomprehensible or unpredictable if we consider violence as a VEO decision variable or concern rather than just a tactic.

In Chapter 6 Timothy Heath and Cortez Cooper provide an analysis of Chinese national security decision making, and in the final chapter Ed Robbins and Hunter Hustus provide the practitioners view of the value of deterrence over compellence in achieving US national security goals.

In addition to their individual contributions, two broader themes emerge when the chapters in this white paper are taken together:

- Internal Structures Condition Decisions and Behavior at all Levels of Analysis. Observable decisions are often the result of competition and interaction between internal systems, beliefs, interests, factions, components or bureaucracies. Even if not the intention, seemingly inconsistent or even self-defeating behaviors and decisions can arise even from normal functioning of these internal components as internal struggles play out in different contexts. This is true at the level of the individual decision maker where different systems in the brain constitute those structures; at the group level where the attractiveness or source of cohesion and the form of interdependence among group members significantly impact group norms and decision; and at the organization level where internal structures such as bureaucracies can incentivize certain choices and make decisions and actions inconsistent.

- Especially in Ambiguous Operating Environments the Analysis of Adversary Decision Making must be Multi-level. Decision making has common features across levels as well as features specific to the each level. As the categorical boundaries between forms of conflict are increasingly replaced by ambiguous operating environments, the best insight into an adversary’s behavior will require study of decision process and contextual factors on multiple levels of analysis (e.g., individual leader integrative complexity within the context of the structure and norms of his decision group and the bureaucratic pressures of his organization).

Contributing Authors

Maj Gen (Sel) Tim Fay (USAF/A3-5), Dr. Allison AstorinoCourtois (NSI), Mr. Cortez Cooper (RAND), Dr. Douglas C. Derrick (University Nebraska Omaha), Mr. Timothy Heath (RAND), Mr. Hunter Hustus (AF/A10), Dr. Gina Ligon (University Nebraska Omaha), Dr. Bonny Lin (RAND), Dr. Clark McCauley (Bryn Mawr College), Dr. Edward Robbins (AF/A10), Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Dr. Nicholas D. Wright (Carnegie)

The Applied Critical Thinking Handbook 7.0.

Author | Editor: TRADCOC G2.

The premise of the program at the University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies (UFMCS) is that people and organizations court failure in predictable ways, that they do so by degrees, almost imperceptibly, and that they do so according to their mindsets, biases, and experience, which are formed in large part by their own culture and context. The sources of these failures are simple, observable, and lamentably, often repeated. They are also preventable, and that is the point of ‘red teaming’.

Our methods and education involve more than Socratic discussion and brainstorming. We believe that good decision processes are essential to good outcomes. To that end, our curriculum is rich in divergent processes, red teaming tools, and liberating structures, all aimed at decision support.

We educate people to develop a disposition of curiosity, and help them become aware of biases and behavior that prevent them from real positive change in the ways they seek solutions and engage others.

We borrow techniques, methods, frameworks, concepts, and best practices from several sources and disciplines to create an education, and practical applications, that we find to be the best safeguard against individual and organizational tendencies toward biases, errors in cognition, and groupthink.

Red teaming is diagnostic, preventative, and corrective; yet it is neither predictive or a solution. Our goal is to be better prepared and less surprised in dealing with complexity.

A Geopolitical and Cognitive Assessment of the Israeli-Palestinian Security Conundrum.

Author | Editor: Wilkenfeld, J. ().

At the request of the U.S. Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority (USSC) the J-39 Strategic-Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Branch undertook a Coordinator’s Mission Review in July 2014 and concluded it in February 2015. This SMA project resulted in an unprecedented collaborative effort among over one hundred subject-matter experts from numerous organizations across the Department of Defense, U.S. Government Departments and Intelligence Agencies, Academia, Think Tanks, and Private Industry. The work of these subject- matter experts is summarized in this white paper.

The purpose of the review was to evaluate strategic risks and identify knowledge gaps in order to provide an increased understanding of potential future security environments and their implications for Palestinian security sector reform. The SMA team focused on producing analyses and tools to address USSC’s questions, which were grouped into three broad categories: internal Palestinian security concerns; challenges to Israeli-Palestinian joint security; and the role of external actors in Israel-Palestinian security. The overall objective was to provide inputs to serve as ongoing planning and training resources for the Security Coordinator’s office. The following document presents a brief summary of the key takeaways from each of the resulting reports.

Chief among the issues that were of concern to USSC was security sector reform in the context of challenges and opportunities of sovereignty in a state of limited arms. Challenges were to be highlighted by addressing the potential impact on the legitimacy and authority of Palestinian security forces in the event of cross-border incursions by Israeli forces in such an environment. Related is the challenge of unity governance under conditions of non-contiguity. USSC was also vitally interested in the role of the international community in supporting the security needs of a functioning future Palestinian state, from the perspective of earning trust, creating transparency, and maintaining legitimacy during third party monitoring missions, as well as examining the linkages between security, economy, and governance in such a state.

Among the key elements reflected in the white paper was a unique collaboration among teams of social scientists to develop and run a simulation exercise designed to identify the key flash points that might result from an increase in autonomy for the West Bank in light of differing security requirements. An international team of area experts, neuroscientists, and social media specialists collaborated with ICONS simulation designers to fashion a unique simulation exercise. USSC staff, along with subject matter experts from the region, took on roles in a fast-paced simulation that first explored areas in which confidence building could take place, followed by a phase of crisis management that put the confidence building to the test. Among the key findings were indications of differing preferences for bilateral versus multilateral talks, potentially constructive use of differing communications pathways in crisis situations, the role that international actors in general, and the US in particular, can play in enhancing security, and key challenges for legitimacy in the face of overwhelming differentials in power and authority.

This white paper outlines insights derived from third-party monitoring missions. The effort derived interesting insights with respect to Israeli-Palestinian joint security and minimum thresholds for security forces. The effort also shed light into insights on internal community investment. Also of interest are case studies the SMA team produced that looked into other states that do not have a significant army. While these case studies are informative and provide interesting insights, the case of the Palestinians is unique with its own set of unique challenges.

This research effort began during a time of considerable optimism that the mission of Secretary of State John Kerry in 2013-2014 would bear fruit at least in terms of the adoption of a framework for an eventual peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, ultimately leading to a two-state solution. Notwithstanding the ultimate collapse of those talks in April 2014 and the fact that the peace process has been in limbo ever since, the authors of this report point out that if and when this process is restarted, the issues addressed in the Coordinator’s Mission Review will again be front and center.

Taken together, the studies reported here can form the basis of effective security sector reform for the Palestinian Authority, and the carving out of a critical role for international actors in general, and the US in particular, in the event that peace talks are resumed and a framework agreement emerges.

Executive Summary

This report evaluates strategic risks and identifies knowledge gaps in our understanding of potential future security environments and their implications for Palestinian security sector reform. Work on this report began almost at the same time as the US-sponsored Israeli-Palestinian peace talks were launched by US President Obama and Secretary of State Kerry in July 2013. While those talks are now on hold, the questions dealt with in the report were geared toward issues that would need to be addressed in any framework agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

Chief among the issues of concern was security sector reform in the context of challenges and opportunities of sovereignty in a state of limited arms, particularly when the stronger neighboring country demands an unspecified level of security. Challenges were to be highlighted by addressing the potential impact on the legitimacy and authority of Palestinian security forces in the event of cross-border incursions by Israeli forces in such an environment. Related is the challenge of unity governance under conditions of non-contiguity. We were also interested in the role of the international community in supporting the security needs of a functioning future Palestinian state, from the perspective of earning trust, creating transparency, and maintaining legitimacy during third party monitoring missions, as well as examining the linkages between security, economy, and governance in such a state.

Notwithstanding the breakdown of the peace talks in April 2014, followed by the Gaza War and subsequent Israeli elections, there is the sense that sooner or later, these issues will need to be addressed in an inevitable future two state solution to this conflict, and that therefore it is important to lay out these issues and some of their mechanisms in anticipation of this eventuality. In the view of the researchers who put the following reports together, these are still the right questions.

The seven questions were grouped into three broad categories: challenges to Palestinian internal security; challenges to Israeli-Palestinian joint security; and the role of external actors in Israel- Palestinian security. In addition, the SMA research team provided an analysis of the socio-political and social-cultural dynamics of the region by analyzing regional social media activity in Arabic. Finally, an international team applied key insights from psychology and neuroscience to the research questions posed.

Key Takeaways

Challenges to Palestinian Internal Security

Q1. What are the critical areas of security sector reform required to make civil society work within the Palestinian Authority and across the territories versus the status quo?

An analysis was conducted by the NSI team to identify Palestinian security sector reform measures that would assist in fostering a healthy and transparent relationship between the Palestinian security sector and Palestinian civil society in the West Bank. A two stage analytic method was used to facilitate the identification of impediments, or barriers, to the provision of security by the Palestinian security sector consistent with acceptable practices of modern security forces and in alignment with civil societies expectations. The methodology enabled identifying security sector reform measures that can both strengthen and solidify the Palestinian security sector in a manner that is popularly accepted and sustainable with the Palestinian civil society. The analysis identified several areas of security sector reform measures and development: clarify confusion over roles and responsibilities of the Palestinian security sector, strengthen legitimacy of the security forces in the eyes of Palestinian civil society and the population, and improve equipping and training of the security forces.

Q2. What are the challenges and opportunities for sovereignty in a state of limited arms?

While Palestinian leaders aspire to a fully sovereign state with defense capabilities, Israel insists on numerous restrictions to neutralize the threat potential. Decades of negotiations have sought common ground to bridge this considerable gap. In this study, ICONS Project researchers at the University of Maryland undertook an empirical analysis of states with limited arms, defined as states with little to no dedicated, external defense capacity. In practical terms, this translates to states without an established military (or only a symbolic force) and low or no military expenditures. Common challenges to sovereignty include a lack of capacity to maintain internal security or defend against non-state actors, dependence on international support, and an inability to cope with external threats. Common opportunities for sovereignty include having more resources to devote to crucial development needs, a more peaceful reputation that demonstrates to regional rivals that they are not a threat, and opportunities to more easily consolidate their independence and internal stability. Mechanisms to preserve sovereignty for limited arms states can be accomplished through the development of robust domestic security forces, international security guarantees and assistance, and international cooperation on defense. In some cases, states also gradually lift the arms limitations and remilitarize to better meet threats as conditions change.

Q3. What are the challenges of achieving unity government and maintaining effective security in non- contiguous states?

The challenges of non-contiguity are at the heart of the efforts to establish a viable Palestinian state. This report by the ICONS research team seeks to inform conversations about what challenges to anticipate and how they might be over come by applying a comparative case study approach. The study identified common challenges to and mechanisms for preserving sovereignty. States with exclaves often face enormous obstacles to ensuring effective governance and security. Some stem from the local population itself, for instance local grievances due to isolation and state neglect and a lack of national sense of belonging. Others emphasize the vulnerability of exclaves without official or easily securable borders, which open the door to conflict and criminality. Finally, relationships matter immensely. Without communication and compromise, differences in law and culture can complicate the rules under which an exclave operates. In more extreme instances, a lack of trust between home state, host state, and exclave populations – or even openly hostile relations – can badly damage the viability of an exclave altogether. But some solutions exist to many commonnon-contiguous state challenges. Many states rely, for instance, on ongoing processes of negotiation with the host state to ensure access to and the smooth functioning of its exclave. Officially demarcating borders, opening up pathways to integrate with the surrounding state, and focusing on policies to improve exclave residents’ welfare also help eliminate many sources of conflict before they emerge. In some cases, joint decision-making structures or enabling local problem-solving also mitigate the difficulties of administering territory from afar. Finally,the military solution is a common, though possibly not entirely desirable option to preserve sovereignty, especially in the face of domestic threats.

Israeli-Palestine Joint Security

Q4. What are the minimum thresholds for indigenous security forces in protecting its citizens and guarding its borders, particularly when the neighbor country demands an unspecified level of security?

Competing security challenges naturally surface for Israelis and Palestinians as they maneuver to gain West Bank areas for their respective homes. While multiple factors contribute to Israeli- Palestinian tension, this study sought to understand the political positions and security interests of Palestinians and Israelis in order to find potential areas of compromise as well as true sticking points. To achieve that aim, the NSI team conducted thematic and discourse analyses on the speeches of leaders across the breadth of the Israeli and Palestinian political landscapes. The analyses suggest that there are important areas of mutual concern that may serve as starting points for negotiation as well as areas of diametric opposition. These include the need for coordinated policing, access to and protection of holy sites and public places, concern about refugees and displaced persons, and management of border areas and crossings. Competing concerns include blockade and embargo of Gaza, Israeli-held Palestinian prisoners, and IDF activities in Palestinian areas.

Q5. With respect to cross-border arrests, prosecutions, and targeted lethal action, what are the challenges, risks, and opportunities to legitimacy and sovereignty between neighbors with competing security requirements?

Question 5 was addressed with two different methodologies. First, the NSI research team derived insights from an analysis of a conceptual map, or qualitative loop diagram that relates Israeli and Palestinian Authority (PA) sovereignty and legitimacy in the West Bank with Palestinian violence and cross-border and Israeli Defense Forces/ Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories Unit (IDF/COGAT) activities. The relationships and feedback loops of Israeli and Palestinian security and political positions reflect the dynamics that drive the security challenges and risks that impact the effectiveness of PA security sector reform and institutional development. The loop analyses identify risks and suggest implications for international community activities. Key findings include:

- PASF capability enhancements can reduce PA legitimacy and limit the effectiveness of security sector reform

- PA governing legitimacy is a critical pre-condition for successful security sector institution building and PASF capacity development

- Israeli security activities have self-reinforcing adverse effects on PA legitimacy and development of security sector institutions

- Uncertainty about the final status of the West Bank and the mainstreaming of settlement populations undermine efforts to re-open settlement talks

In a separate analysis, the ICONS simulation group was charged with developing a simulation to address Question 5. The following objectives for the simulation were identified: (1) Gain insights on opportunities/challenges to effective confidence-building and crisis management when faced with competing security requirements; (2) Identify capabilities and contingencies which will be most useful for helping the PASF cope with legitimacy issues; and (3) Provide insights that can be brought to the inter-agency/broader USG stakeholders as deemed appropriate. The problem space for the simulation exercise focused on potential IDF incursions into Palestinian-controlled territories (Area A on the West Bank). The scenario comprised of two phases – confidence building and crisis management. Key findings were organized into the categories of communications dynamics, political/media dynamics, and key tensions for legitimacy. Key findings addressed communications dynamics (PA preference for multilateral, Israeli preference for bilateral), preferred communications pathways, differing perceptions of international and US responsiveness, and political and media dynamics. Key tensions for legitimacy included misperceptions, the IDF presence, disagreements over investigations, the role of the NSF, PA frustration over competing priorities for their security and political leaders, the role of Israeli public opinion, and strain for the PA viewed as normal by Israel. [See also Neuroscience/Psychology analysis]

The Role of External Actors in Israel-Palestinian Security

Q6. What are best practices for international security forces in earning trust, creating transparency, and maintaining legitimacy during third party monitoring missions?

A third party monitoring mission could play a potentially significant role in guaranteeing a future Israeli-Palestinian peace deal. This report by the ICONS team aims to inform conversations about the ideal design by engaging in a qualitative comparative case study analysis of past missions. The report starts with a brief overview of the literature on third party monitoring and a presentation of characteristics that are helpful for analyzing and comparing missions. Five historical cases were selected for in-depth analysis: the EU Monitoring Mission in Georgia (EUMM), the International Monitoring Team in the Philippines (IMT), the Truce/Peace Monitoring Group in Papua New Guinea (TMG/PMG), the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM), and the UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE). Strategies from each of the missions were collected and synthesized into a list of best practices for future missions. For maintaining legitimacy: obtain parties’ consent and buy-in, establish clear expectations, demonstrate commitment and follow-through, allow for mission evolution, and develop exit strategy in conjunction with the parties. For earning trust: invest in pre-deployment training and diverse teams, exhibit impartiality through mission structure and action, serve as bridge between parties, foster good relations with locals, and work collaboratively with third parties and peace groups. For creating transparency: be visible and accessible, communicate regularly and publicly, develop clear structures and consistent operating procedures, explain when secrecy is required, and distinguish the mission from other actors. The report concludes with an appendix detailing the characteristics of a future Israeli-Palestinian third party monitoring mission focused on earning trust, creating transparency, and maintaining legitimacy.

Q7. With respect to the linkages between security, economy, and governance, and with recognition that each is needed to support a functioning state, where should the international community invest?

This report looks at the multiple factors that contribute to instability in the West Bank. Palestinians face escalating levels of economic, social, and governing instability that, in turn, serve to degrade the governing legitimacy of the Palestinian Authority (PA). Using the NSI Stability Model (StaM) and Analysis, the NSI team identified key buffers and drivers of economic, social, and governing stability along with their second- and third-order effects. The report also identifies several considerations for analysts on where and how the international community can invest that may help to decrease instability while avoiding investing in channels that could lead to further instability. The key findings include the following: Political stalemate on the West Bank degrades perception of PA legitimacy while the PASF is feared and seen as working with the IDF and violating human rights. Declines in foreign aid and continue VAT withholdings are causing a cascading of impacts that are crushing the economy, preventing payroll payments, harming the environment, and impairing basic human rights and needs. High unemployment among youth and inappropriate job training coupled with a climate of conflict could lead to uprisings in this group. Increased limits on protests and speech further a growing discontent and risk retaliatory actions.

NSI Chapters:

- Internal Palestinian Security Dilemmas (A. Desjardins, S. Pagano, T. Rieger, R. Popp)

- Competing Security Challenges (L. Kuznar, M. Yager, K. Key)

- Legitimacy and Sovereignty in an Environment with Competing Security Requirements (A. Astorino-Courtois, B. Bragg, K. Key)

- Optimizing the Impact of International Community Investment in Security, Economy, and Governance to Support a Functioning State (T. Rieger, S. Pagano, D. Brickman, G. Popp, R. Popp, K. Key)

Contributing Authors

Mr. Ben Riley (OSD), Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI), Ms. Lauren Barr (ICONS), Ms. Belinda Bragg (NSI), Dr. Danette Brickman (NSI), Mr. Jose Miguel Cabezas (ICONS), Ms.

Abigail Desjardins (NSI), Mr. Devin Ellis (ICONS), Ms. Kimberly Key (NSI), Dr. Randy Kluver (Texas A&M University), Dr. Larry Kuznar (NSI), Dr. Jacquelyn Manly (Texas A&M University), Dr. Sabrina Pagano (NSI), Mr. George Popp (NSI), Dr. Robert Popp (NSI), Mr. David Prina (ICONS), Mr. Tom Rieger (NSI), Dr. Sara Savage (University of Cambridge and ICthinking), Dr. Jonathan Wilkenfeld (ICONS), Dr. Nicholas Wright (Carnegie), Ms. Mariah Yager (NSI)

Operating in the Human Domain 1.0.

Author | Editor: U.S. Special Operations Command.

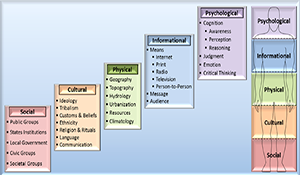

Building on the vision of USSOCOM strategic guidance documents, the Operating in the Human Domain (OHD) Concept describes the mindset and approaches that are necessary to achieve strategic ends and create enduring effects in the current and future environment. The Human Domain consists of the people (individuals, groups, and populations) in the environment, including their perceptions, decision-making, and behavior. Success in the Human Domain depends on an understanding of, and competency in, the social, cultural, physical, informational, and psychological elements that influence human behavior.2 Operations in the Human Domain strengthen the resolve, commitment, and capability of partners; earn the support of neutral actors in the environment; and take away backing and assistance from adversaries. If successful in these efforts, Special Operations Forces (SOF) will gain military, political, and psychological advantages over their opponents. The OHD Concept integrates existing capabilities and disciplines into an updated and comprehensive approach that is applicable to all SOF core activities.

SOF personnel continuously think about human interactions, building trust, and winning support among individuals, groups, and populations. Drawing on the approach and required capabilities identified in this concept, SOF and its partners use persuasion and compulsion to shape the calculations, decision-making, and behavior of relevant actors3 in a manner consistent with mission objectives and the desired state.4 SOF must win support and build strength, before confronting adversaries in battle. Working in collaboration with capable partners and as part of a whole-of-government approach, SOF enables preemptive actions to avert conflicts or keep them from escalating. When necessary, SOF and its partners confront and defeat adversaries, always mindful that the end goal is an eventual cessation of hostilities and a more sustainable peace.

SOF conduct enduring engagement in a variety of strategically important locations with a small-footprint approach that integrates a network of partners. This engagement allows SOF personnel to nurture relationships prior to conflict. Language and cultural expertise are important, but SOF’s ability to shape broader campaigns with allies and partners to promote stability and counter malign influence is vital. SOF leaders plan and execute operations that support national objectives, while providing continuous analysis and advice to ensure effective strategy. SOF must identify and assess relevant actors, understand their past and current decisions and behavior, and anticipate and influence their future choices and actions across the ROMO.

SOF contribute to the accomplishment of U.S. policy objectives during peaceful competition, non-state and hybrid conflicts, and wars among states. The ideas in the OHD Concept are key to confronting state and non-state actors that combine conventional and irregular military force as part of a hybrid approach. Adversary states are increasingly adapting their methods to negate current and future U.S. strengths, relying on non-traditional strategies, including the use of subversion, proxies, and anti- access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. These adversary strategies require a refined U.S. approach for effective counteraction. A critical goal will be to create conditions that shape adversary decisions and behavior in a manner that favors U.S. objectives or develops opportunities friendly forces can exploit to achieve the desired state.

Multi-Method Assessment of ISIL in Support of SOCCENT: Subject Matter Expert Elicitation Summary Report, July – November 2014.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Rieger, T. (NSI, Inc).

From July through November 2014, NSI conducted a Subject Matter Expert (SME) Elicitation study to gather insights from interviews, panel discussions, seminars, and personal communications with over 50 SMEs from the United States, the Middle East, and Europe. The interview questionnaire and transcripts from the SME elicitation effort are available upon request. CTTSO provided the Apptek Talk2Me platform to expedite the transcription of the SME Elicitation interviews. In addition, all of the data (human edited and original audio) are posted on the Web-based Talk2Me platform for the SMA study for further analytics and reporting.

This report summarizes SME findings that help us understand ISIL’s intangible appeal. However, it does not attempt to adjudicate or force convergence of the findings.

Conditions: The Perfect Storm

Some SMEs described conditions on the ground as a “perfect storm” for the emergence of ISIL. The confluence of the conditions listed below allowed ISIL to rise rapidly.

- Failed states of Iraq and Syria: The power vacuum in the Sunni regions of Iraq and Syria opened the door for an alternative governing force to coalesce and gain the acquiescence and/or support of the civilian 3 population.

- Sunni grievances: The combination of political exclusion of Sunnis from government in Iraq and Syria along with the abuses visited upon Syrian Sunnis by the Assad regime have fed narratives of Sunni grievance, victimization, and marginalization.

- Arab world undergoing rapid change: ISIL is an expression of rising Islamist fundamentalism, declining sense of state-based nationalism, and a sense of empowerment spurred by the Arab Spring.

- Information Age: The advent of the information age makes it easier for people to communicate across large distances, to create a platform for sharing experiences and beliefs with like-minded individuals, and to actively persuade others to sympathize with or join a cause.

- Youth bulge: Like many parts of the developing world, Syria and Iraq are experiencing a youth bulge that, when combined with unemployment and lack of political voice, has resulted in a reservoir of young, angry men.

On the whole, SMEs felt that these conditions made it possible for ISIL to seize the opportunity to push for an alternative form of governance in the region. However, while these conditions were extremely important, ISIL’s sustainability and longevity is also based on its capacity to control the population and to garner sympathy and support from the broader Sunni Muslim population both inside and outside the region.

Capacity to Control

SMEs believed that ISIL’s capacity to control is based on several factors.

- Fear and coercion: ISIL has a monopoly over the use of force in areas it “governs.” It uses the implicit and explicit threat of violence against civilians to ensure acquiescence.

- Provision of better governance and order: Some argue that ISIL provides better governance and essential services than what was experienced under Iraqi and Syrian rule. Furthermore, ISIL provides some degree of stability and order in a previously uncertain environment.

- Lack of a viable alternative: There are currently no alternative forms of Sunni-empowered governance available. ISIL draws on the power of collective Sunni identity and Sunni grievances to establish its legitimacy.

- Strong leadership: ISIL has a strong, agile, pragmatic leadership and organizational structure. It has a highly motivated and a dedicated rank and file under the leadership of a disciplined and experienced cadre, supported by consistent and compelling messaging.

- Success breeds success: ISIL’s momentum and its ability to survive coalition attacks to date plays a role in convincing civilians and local power brokers that it will be around for the long-term, which reinforces support or acquiescence to ISIL, and in turn further reinforces ISIL’s capacity to control.

ISIL’s capacity to control is largely based on its interactions with the local population. However, ISIL also enjoys sympathy, support, and recruits from the global Sunni Muslim population. SMEs interviewed felt that the primary way ISIL achieves support from the global Sunni Muslim population is through persuasive use of narrative. SMEs identified over 20 narratives ISIL uses to persuade, the most powerful of which are described below.

Persuasive Narratives

Narratives are messages that represent the ideals, beliefs, and social constructs of a group. ISIL uses them within the civilian population to consolidate control and amongst the global Sunni Muslim population to garner sympathy, support, and recruits.

- Moral imperative: ISIL uses a variety of narratives to convey the idea that Muslims have a moral imperative to support them. These narratives include the restitution of the caliphate, creation of a utopian society based on Muslim laws and values, ISIL as a representative of the pure form of Islam, ISIL bringing back the Golden Age of Islam, al Baghdadi as a direct descendent of the Prophet, and that ISIL’s caliphate will unite all Sunni Muslims.

- Sunni grievances and victimhood: ISIL uses shared feelings of marginalization, repression, and lack of power to gain legitimacy and support. They draw on sub-narratives of victimization among Sunnis at the hands of Shias and the West to cement this powerful narrative.

- Immediacy: ISIL rejects al Qaeda’s core narrative that it needed to wait for the right time to establish a caliphate. ISIL claims that they did it within months. ISIL touts its willingness to take action, combined with its success in establishing what it calls a caliphate, as evidence of their proclaimed righteousness and destiny.

- Reinvention of self: No matter what kind of life you led, when you convert to Islam and join the fight, all previous wrongdoing is washed away. ISIL offers a new start and a new sense of identity and purpose to anyone who joins them.

- Thrills, adventures, and heroism: Some individuals are particularly drawn to ISIL because it advertises thrills, adventures, and opportunities for heroism (and violence) that appeal to some young men’s sense of masculinity.

Schools of Thought

While these factors represent areas of qualified agreement on key factors explaining ISIL support, SMEs differed on which factors were the most important, which led to two primary schools of thought regarding ISIL’s longevity.

- The first school of thought is ISIL has resilient properties via its capacity to control people and territory stemming from pragmatic leadership and organization, intimidation tactics, tapping into existing Sunni grievances and use of a well-developed narrative and media outreach to attract and motivate fighters.

- The second school of thought is ISIL is not a durable organization. It has taken advantage of a pre-existing sectarian conflict to acquire land, wealth, and power. It only attracts a narrow band of disaffected Sunni youth, is alienating local populations by over-the-top violence and harsh implementation of Sharia, is unable to expand into territories controlled by functioning states, and does not possess the expertise required to form a bureaucracy and effectively govern.

In reviewing the effort, a third school of thought emerged: that the real challenge is not ISIL as an organization, but rather the sense of disempowerment, anger, and frustration in the Muslim world. This condition is evidenced by rising Islamist fundamentalism found within Sunni Muslim populations around the world combined with a declining sense of state-based nationalism. It is fueled by a perception of inequality and thwarted aspirations in addition to the conditions mentioned earlier in this chapter: failed states, demographic shifts, unemployment, drought, spread of communication technologies, marginalization, etc. If the problem is larger than ISIL, then solutions that only seek to undermine ISIL’s capacity to control are insufficient to address the underlying cause of conflict, as they address only the symptoms of the problem and not the underlying root cause.

Additional Factors

This summary presents a cursory review of the many topics addressed by over 50 SMEs interviewed for this effort. In addition, the report also touches on a number of other controversial topics. These include:

- whether ISIL is primarily ideological or opportunistic;

- whether the local elite power base in Iraq and Syria sincerely supports ISIL;

- situational factors contributing to the sustainment of ISIL;

- the degree to which regional Sunni Muslim states support or oppose ISIL; and

- a brief look at whether the rise of other historical violent social movements could be instructive.

SME elicitation through the SMA SOCCENT Speaker Series will continue. To be added to the distribution list for the series, please contact Mr. Sam Rhem at samuel.d.rhem.ctr@mail.mil.

Comprehensive Deterrence White Paper.

Author | Editor: U.S. Army Special Operations Command.

The emerging concept of Comprehensive Deterrence is an initial effort to broaden strategic options for our National leaders to meet current and emerging security challenges. Comprehensive Deterrence internalizes the challenge from then Secretary of Defense Hagel’s Defense Innovation Memorandum (15 November 2014) to pursue innovative ways to sustain and advance U.S military superiority for the 21st Century. Comprehensive Deterrence also acknowledges the guidance from General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on 11 January 2015 when he noted that, “We’re going to have to think our way through the future, not bludgeon our way through it.”

Comprehensive Deterrence seeks to expand upon traditional concepts of deterrence to account for the totality and the variety of the threats we face in the early 21st Century security environment. It posits that deterrence, particularly on the left-side of the operational continuum, is not only about preventing something from happening, but also about preventing something from escalating beyond our strategic depth and our capability to respond, in a manner consistent with our National values.

Comprehensive Deterrence is defined as the prevention of adversary action through the existence or proactive use of credible physical, cognitive and moral capabilities that raise an adversary’s perceived cost to an unacceptable level of risk relative to the perceived benefit.

Key themes within the concept of Comprehensive Deterrence include: 1) Existing theories of deterrence generally focus on high-end conflict conducted by Nation States on the right-side of the operational continuum. Investment in deterrence thinking on the left-side of the operational continuum is warranted to meet the growing challenges the United States and its Allies face in the Gray Zone; 2) The totality of the security challenges and the varied nature of these challenges require reframing of what constitutes strategic power and strategic risk in a complex and unpredictable world; 3) The growing trans-regional aspects of competition and conflict require new planning models, new operational constructs, new ways of thinking, and fully integrated partner networks to rescale security challenges earlier in their trajectory; 4) Select state and non- state actors are effectively operating in the Gray Zone, which demands study of how we build the nuanced inter / intra governmental multi-year campaigns that are required to successfully compete and win in this space; and 5) Comprehensive Deterrence points to a grand strategy to deliver more effective security for the Nation.

The conceptual lines of effort within Comprehensive Deterrence are; 1) Expanding the Strategic Start Point, 2) Rethinking Strategic Power and Reframing Power Projection with two sub- components, Partner Based Power and Population Based Power, 3) Rethinking Asymmetric Approaches, 4) Rethinking the Strategic Nexus between the Land and Human Domains, 5) Broadening Considerations of Strategic Risk, and 6) Expanding Technology Solutions for the Human Domain.

The concept of Comprehensive Deterrence is an outgrowth of the United States Special Operations Command’s (USSOCOM) and the United States Army Special Operations Command’s (USASOC) futures and wargaming platforms. The adjective, comprehensive, speaks to deterrence across the operational continuum and to the application of a Whole of Government / Whole of Partner framework to enable its full realization.

Barriers to Civil Order in Palestinian Security Sector

Author | Editor: Desjardins, A., Polansky (Pagano), S., Popp, R. & Rieger, T. (NSI, Inc).

The origins of the Palestinian security sector can be traced to the 1993 Oslo I Accord, which established divisive security and policing responsibilities between the Palestinians and Israelis and the Oslo II agreement, which codified interim boundaries, including the division of the West Bank into a complex and fragmented patchwork of different jurisdictions. These divisions of land and security responsibilities remain in place to this day and have fostered a unique, complicated, and at times perplexing situation for both the Palestinian security sector and the civil society it serves to protect. The environment in the West Bank is replete with confusion over security sector authorities and responsibilities, frustration over barriers1 to the provision of security and justice, and fear and mistrust of the security sector forces. Moreover, the absence of publically available mission statements and codified legal documents, that clearly delineate the Palestinian security sector roles and responsibilities, adds to the complex situation.

At the request of the United States Security Coordinator (USSC) staff, an analysis was conducted to identify security sector reform measures that would assist in fostering a healthy and transparent relationship between the Palestinian security sector and Palestinian civil society in the West Bank. To this end, we focused on assessing the performance of the Palestinian security sector in the provision of security to the Palestinian civil society via a two stage analytic methodology. First, we conducted a qualitative assessment comparing Palestinian security sector functions and activities that are authorized based on legal documents with those that are reported via news reports and by civil society, and, second, we compared this with acceptable practices in the provision of security consistent with modern security forces. To simplify and clearly convey our analysis, we utilized “living” Venn diagrams, which allows for the rapid integration of additional data and information as they become available. This was followed by a barrier analysis identifying internal and external barriers and their associated root causes in the provision of security that is not in alignment with Palestinian civil society perspectives and expectations. The identification and classification of barriers and their root causes facilitates the detection of points for security sector reform measures that can both strengthen and solidify the Palestinian security sector in a manner that is popularly accepted and sustainable with the Palestinian civil society.

Overall, our analysis identified five primary barrier categories in the provision of security by the Palestinian security sector—fear based barriers, clarity and alignment barriers, population engagement barriers, capability barriers, and legal barriers. Several external barriers, which are based on factors or influence outside of Palestinian control, were identified (e.g., culture of fear and limitations on movement or other activities). These factors are more difficult to overcome in the current environment in the West Bank and, in many cases, may be rooted in an intractable problem. However, several internal barriers, such as insufficient legal frameworks or lack of preparedness, that are within the control of the Palestinian security sector were identified. This suggests that mitigating actions can be taken by the Palestinian security sector in partnership with international partners, even given the currently limiting socio3political environment in the West Bank, to reduce or dampen their effect on the provision of security.

Thus, drawing from our analysis, several high3level security sector reform measures and mitigation strategies emerged. Our analysis suggests several focus areas for security sector reforms and development. Each is critical to the provision of security in the Palestinian Authority, is consistent with acceptable practices of modern security forces, and should facilitate civil society involvement.

Clarify confusion over roles and responsibilities—support the creation of clear, comprehensive, and codified legal documents laying out the missions and duties of each Palestinian security sector entity; this helps ensure accountability of and trust in the Palestinian security sector and its ability to ensure the safety of its citizens.

- Guide Palestinian security sector toward completion of comprehensive legal documents that delineate Palestinian security sector forces mission and duties in clear language;

- Ensure that guidelines establish the lines of authority and purview within and across the forces;

- Emphasize common Palestinian identity and goals as part of a superordinate ingroup, but avoid the pitfall of reinforcing Israel as the outgroup;

- Work to establish a more cohesive security philosophy that can guide all of the Palestinian security sector forces in pursuit of a common goal.

Strengthen legitimacy—take measures to re3establish the trust of Palestinian civil society in its security sector forces in order to promote cooperation and adherence, as well as smooth the path for the Palestinian security sector to perform its duties once they are more clearly and explicitly defined and established.

- Guide Palestinian security sector toward establishing formal complaint and feedback systems, which will not result in retribution;

- Establish protocols and training that facilitate respectful and fair treatment of members of Palestinian civil society and avoid human rights abuses;

- Emphasize the proper selection of candidates for jobs at the individual and aggregate level

- Work to reduce cronyism and other forms of bias in employment selection;

- Encourage organizations to take responsibility for missteps and apologize to the population as needed when mistakes are made;

- Work to establish an effective witness protection program;

- Work to more generally increase transparency and accountability;

- Work to establish independent oversight, for example, through the appointment of an ombudsman to investigate citizens’ complaints.

Improve equipping and training of forces—critical for Palestinian security sector to effectively execute its duties is having sufficient equipment and training, although this issue may be less easily resolved due to dependence of the Palestinian Authority for Israeli approval of materiel.

- Prioritize the establishment and funding of an improved communications infrastructure for security;

- Work to centralize training facilities;

- Streamline training curricula to emphasize common principles and needs across security organizations, while maintaining differentiation as needed;

- Perform an audit of existing training;

- Assess remaining training needs based on pain points after the higher priority goals have been met and/or barriers have been mitigated;

- Ensure that training maps to the overarching security philosophy that should be established in advance.