SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine, Soviet Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Warfare.

Author | Editor: Snegovaya, M. (Institute for the Study of War).

Russia has been using an advanced form of hybrid warfare in Ukraine since early 2014 that relies heavily on an element of information warfare that the Russians call “reflexive control.” Reflexive control causes a stronger adversary voluntarily to choose the actions most advantageous to Russian objectives by shaping the adversary’s perceptions of the situation decisively. Moscow has used this technique skillfully to persuade the U.S. and its European allies to remain largely passive in the face of Russia’s efforts to disrupt and dismantle Ukraine through military and non-military means. The West must become alert to the use of reflexive control techniques and find ways to counter them if it is to succeed in an era of hybrid war.

Reflexive control, and the Kremlin’s information warfare generally, is not the result of any theoretical innovation. All of the underlying concepts and most of the techniques were developed by the Soviet Union decades ago. Russian strategic theory today remains relatively unimaginative and highly dependent on the body of Soviet work with which Russia’s leaders are familiar. Russian information operations in Ukraine do not herald a new era of theoretical or doctrinal advances, although they aim, in part, to create precisely this impression. Russia’s information warfare is thus a significant challenge to the West, but not a particularly novel or insuperable one.

It relies, above all, on Russia’s ability to take advantage of pre-existing dispositions among its enemies to choose its preferred courses of action. The primary objective of the reflexive control techniques Moscow has employed in the Ukraine situation has been to persuade the West to do something its leaders mostly wanted to do in the first place, namely, remain on the sidelines as Russia dismantled Ukraine. These techniques would not have succeeded in the face of Western leaders determined to stop Russian aggression and punish or reverse Russian violations of international law.

The key elements of Russia’s reflexive control techniques in Ukraine have been:

- Denial and deception operations to conceal or obfuscate the presence of Russian forces in Ukraine, including sending in “little green men” in uniforms without insignia;

- Concealing Moscow’s goals and objectives in the conflict, which sows fear in some and allows others to persuade themselves that the Kremlin’s aims are limited and ultimately acceptable;

- Retaining superficially plausible legality for Russia’s actions by denying Moscow’s involvement in the conflict, requiring the international community to recognize Russia as an interested power rather than a party to the conflict, and pointing to supposedly-equivalent Western actions such as the unilateral declaration of independence by Kosovo in the 1990s and the invasion of Iraq in 2003;

- Simultaneously threatening the West with military power in the form of overflights of NATO and non-NATO countries’ airspace, threats of using Russia’s nuclear weapons, and exaggerated claims of Russia’s military prowess and success;

- The deployment of a vast and complex global effort to shape the narrative about the Ukraine conflict through formal and social media.

The results of these efforts have been mixed. Russia has kept the West from intervening materially in Ukraine, allowing itself the time to build and expand its own military involvement in the conflict. It has sowed discord within the NATO alliance and created tensions between potential adversaries about how to respond. It has not, however, fundamentally changed popular or elite attitudes about Russia’s actions in Ukraine, nor has it created an information environment favorable to Moscow.

Above all, Russia has been unable so far to translate the strategic and grand strategic advantages of its hybrid warfare strategy into major and sustainable successes on the ground in Ukraine. It appears, moreover that Moscow may be reaching a point of diminishing returns in continuing a strategy that relies in part on its unexpectedness in Ukraine. Yet the same doctrine of reflexive control has succeeded in surprising the West in Syria. The West must thus awaken itself to this strategy and to adaptations of it.

Drivers of Conflict and Convergence in the Asia-Pacific Region in the Next 5-25 Years.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc).

USPACOM requested that the Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) team conduct an “Examination of future political, security, societal, and economic trends to identify where US interests are in cooperation or conflict with Chinese and other interests particularly in the East China Sea.” More specifically, USPACOM requested an examination of future political, security, societal, and economic trends; identification of where US strategic interests are in cooperation or conflict with Chinese and other interests, particularly in the East China Sea; and suggestions as to how USPACOM might best leverage opportunities when dealing with China in a “global context.” The project request also included a series of questions (see Appendix A) that, taken together represent two broad concerns.

- The Nature of the Future Operating Environment. Namely, how should USPACOM planners envisage the threats and opportunities represented by the Asian environment over the next 5, 10 to 25 years? (Questions 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8)

- US Engagement Policy. Specifically, what are the key components of a regional engagement policy centered on China that empowers US partners and allied interests to foster multi-lateral defense of strategic stability in USPACOM’s AOR? (Questions 9, 5, 6, 10 and 11)

The primary objective of this project was to provide decision makers the tools to make better sense of the non-linear dynamics and feedback mechanisms at play in the complex environment in which they, and their competitors, operate in the Pacific region and, by doing so, broaden the horizon of strategic thinking and inform planning.

SMA convened a multidisciplinary group of eleven teams drawn from government, industry, think tanks, and universities. The individual teams employed multiple methodological approaches, including strategic analytic simulation and qualitative, quantitative, and mixed analyses to address USPACOM’s questions. This integration report focuses on the qualitative and quantitative analyses conducted by the think-tank and industry teams (CEIP, CSIS, Monitor 360) and academic teams (START, TAMU, UBC) that informed the simulation and modeling work done by the other teams (GMU, NPS, ICONS).

Executive Summary

Evaluating strategic risk in the Asia-Pacific region over the next two to three decades is a complex challenge that is vital for USPACOM planning and mission success. Based on current trends, it appears that what some have dubbed the ‘Asian Century’ may be taking shape. By 2020, three of the five largest economies in the world and more than half of the ten largest militaries in the world will be located in Asia, and more than half of the world’s population will soon reside in the region. How well the United States (US) responds to emerging opportunities and threats to its interests will be determined by the depth of its understanding of the diverse set of political, economic, and social factors in the region. A better understanding of the priorities and interests that drive the “rise” of China, Asia’s largest country, as well as the likely global consequences of its actions will help planners and policy makers both anticipate and respond to future developments. A multi-disciplinary framework that combines these needs could provide valuable insight in dealing with this complex and evolving issue.

The diverse range of approaches and sources utilized by the individual teams involved in this project is one of the strengths of the SMA approach; however, it also makes comparison and synthesis across individual analyses more challenging. The findings from this project are integrated using an interest- based framework. Most broadly, these interests can be categorized as security (preservation of the state and military security), economic (economic prosperity and development), and prestige (international influence and standing). National interests generate economic, social, and international prestige objectives for states, which in turn inform their foreign policy goals and underpin a state’s position and response to specific issues that arise in regional relations. Domestic constraints and pressures can intervene between national interests and foreign policy objectives, potentially changing the nature of that objective, its relative salience, or both.

Without an understanding of the national interests and objectives of both sides, anticipating the likely consequences of any action to influence an issue becomes a matter of luck. The potential of a situation or action to create conflict or cooperation between states is a function of how those states’ interests align and whether their leadership perceives these interests to align or conflict. When interests lead states to seek or prefer different outcomes, conflict (not necessarily military) is created and all states involved face some risk that their interests will be threatened, although if they prevail, there is also opportunity to further or secure an interest. When the interests of states align and all involved can benefit from the same outcome, opportunity also exists. Consciously or not, state leaders and decision makers attribute objectives, goals, interests, and intentions to other states, and interpret their actions in light of these attributions.

Contributing Authors

Swaine, M. ( Nicholas Eberstadt, M. Taylor Fravel, Mikkal Herberg, Albert Keidel, Evans J. R. Revere, Alan D. Romberg, Eleanor Freund, Rachel Esplin Odell, Audrye Wong, CEIP. Dr. Belinda Bragg, NSI. Dr. John Stevenson, UMd. Lt Gen (Ret) Dr. Robert Elder, Dr. Alex Levis,

GMU. Dr. Rita Parhad, Mr. Jordan D’Amato, Mr. Seth Sullivan, Monitor-360. Dr. Peter Suedfeld, Brad Morrison, UBC. Dr. Randy Kluver, Dr. Jacquelyn Chinn, Dr. Will Norris, TAMU. Dr. Clifford A. Whitcomb, Dr. Tarek Abdel-Hamid, Dr. CAPT Wayne Porter, USN (Ret), Mr. Paul T. Beery; Mr. Christopher Wolfgeher; Mr. Gary W. Parker, CDR Michael Szczerbinski, USN; Major Chike Robertson, USA (Naval Postgraduate School)

In pregNSI participated in a large effort focused on identifying areas of strategic risk and opportunity in the Asia-Pacific region over the next two decades. A rising China resides within a very dynamic Asia-Pacific region. A long list of Chinese influence and investment activities abroad together with an active military enhancement program indicate that China is positioning itself to pursue national security interests well beyond the Pacific Rim. As Chinese interests and policy objectives broaden to farther reaches of the globe there is greater likelihood that they will run up against key US international interests. The intersection of US and Chinese interests could represent either a source of conflict or opportunity for cooperation. The main question that US policy makers and planners must consider carefully is: Where and which Chinese interests are most likely to conflict with US global interests, and where may there be opportunities for cooperation? The current problem this project addressed is uncertainty about the likely trajectory of increasingly global Chinese national interests abroad and how these relate to key US interests. The primary objective was to provide decision-makers the tools to make better sense of the non-linear dynamics and feedback mechanisms at play in the complex environment in which they, and their competitors, operate in the Asia-Pacific region, and broaden the horizon of strategic thinking and inform planning.

NSI utilized techniques from our human behavior analytics to examine future political, security, societal, and economic trends; identify where US strategic interests are in cooperation or conflict with Chinese and other interests worldwide, and in particular, to the East China Sea; and assess drivers of divergence, conflict, and convergence when dealing with China in a global context. NSI developed the US-PRC Global Engagement Framework based on the inputs and variety of analytic results produced by other team members to facilitate consistent and coherent integration. Some “key parameters” of the US-PRC Global Engagement Framework included US-China economic trade barriers, imbalances, opportunities, environmental concerns, food security, agricultural policies, water management, carbon-based fuel alternatives, scarcity of resources (competition and cooperation), freedom / denial of access and intrusion issues, military challenges and opportunities, technology and academic exchanges, human rights, national demographics and their impacts on economies, human migration, and third world development. NSI also helped bridge strategic level analysis and operational level needs to ensure the concepts, analyses and results were actionable for end-users such as military planners, strategists and/or decision-makers.

The following is the list of reports completed in support of this effort. Reports and events can be accessed via the links provided

*Reports without a link can be requested by emailing mariah.c.yager.ctr@mail.mil from a .mil or .gov email address.

Reports

In progress

8th Annual SMA Conference: A New Information Paradigm? From Genes to ‘Big Data’ and Instagram to Persistent Surveillance…Implications for National Security.

Author | Editor: Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff) & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

We live in an age characterized by the reshaping of society through the presence of information and networks. The proliferation of information technologies from the micro and instantaneous to the insights hidden in “big data” has generated a range of new issues with implications for global transformation and political power shifts, patterns of conflict and warfare, and potential opportunities for enhancing global stability. The time is right for a thorough consideration of the implications of this “age” on US national security issues. How can we best understand the near-term and long-term consequences of these changes? What adaptations to our current intellectual frameworks, intelligence processes, organizational structures, command and control practices and planning approaches may be necessary? In short, how can the United States Government (USG) and its allies recognize the risks as well as the opportunities for enhanced global security presented by fuller realization of the “information age”?

The intent of the Conference was to examine the implications of the information/network age. What are its key dynamics? What impact do these dynamics have on national security-related topics? And, what changes in USG modes of planning, operation, policy development, and military capabilities are needed to mitigate information age risks while simultaneously recognizing and seizing opportunities?

The 2014 Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Conference focused on these opportunities and challenges from various perspectives and disciplines including neuroscience, behavioral and social sciences, and operational strategy. Emphasis was placed on the need to interweave these various disciplines and perspectives. As in previous years, the conference sought to address the needs of the Geographical Commands. Representatives from the Commands discussed their pressing needs and key operational requirements. SMA’s wide network of experts as well as conference participants assisted in identifying and discussing capabilities that could match these needs.

Opening Session

CAPT Todd Veazie, NCTC, opened the conference. He stated that SMA’s objective is to provide deep contextual orientation and decision quality assessment to warfighting commanders on intractable problems. Brig. Gen. David Béen, JS/JL39, added that SMA’s multi-disciplinary, multi-agency approach does not exist anywhere else in the Department of Defense (DOD). We are living in challenging times, and we need multidisciplinary expertise from across industry, academia, think tanks, and others.

Mr. Ben Riley, PD DASD (EC&P), then questioned whether we are in a different or unique era compared to any other time in history. The Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) studied this question and determined that today is similar to the pre-World War I era in terms of a recent revolution (industrial and information respectively), rise of great powers, struggle of traditional nation states, and global communications advances. He emphasized that it is critical that we understand that global events arise from previous conflict, conditions, and events.

Keynote Speaker: LTG Ed Cardon, US ARMY Cyber Command

LTG Cardon stated that he believes we are in a new global paradigm brought about by the information/technical revolution. Due to this, threats and vulnerabilities are increasing, often in highly complex ways. The US military is dominant in the operational environment, but is losing strategically because we struggle in the information environment. We are in a political struggle and cyber operations are key to success in this area. Cyber operations could be used in all phases of conflict, but particularly in phase 0 and phase 1. He hoped that organizations like SMA could help bridge the gap between the operational and information environments.

Keynote Speaker: Admiral Michael Rogers, Commander, U.S. Cyber Command and Director, National Security Agency/Chief, Central Security Service

ADM Rogers stated that in the digital age, the DOD has to be an agile organization that is capable of quickly building communities of interest in response to wide-ranging, unanticipated crises (such as Ebola). Big data provide new opportunities to distill critical information from the noise to generate insight and knowledge. However, in order to harness the power of information, we have to create partnerships with individuals and organizations we have never worked with before from the private sector, industry, academia, NGOs, think tanks, individuals, and others. That is why the tools and methodologies developed by the SMA community are so important.

Panels

Panel One examined complexity, interdependence, and emergence in an interconnected information age. The demographic/age change we are experiencing is the central issue facing the United States today because of newly emerging threats and opportunities that are arising and will continue to do so. It is essential to understand the nature and character as well as the dynamics of the information age. There is an incredible amount of data constantly being collected in the world today because of the information boom, but the ultimate challenge is figuring out how to make sense of the signal in all of that noise to help better understand the emerging threats and opportunities. The world today consists of a very complex and uncertain environment characterized through interconnectedness and increased competition over resources. Thus, it is time to shift our focus beyond predictability and instead focus more on sense making. We are overwhelmed with data and we need new tools and methodologies to use this data to make sense of an uncertain environment. The United States must start focusing on opportunities to shape the rapidly changing environment and ultimately become more strategic and adaptive in its planning. With the world today being in an age of transition, from the past we learn that the most important factor in determining the success or failure of world systems during times of transition is the system’s willingness or resistance to accept change. However, in reality, today we are rather conservative and overall resistant to change.

Panel Two discussed the information age, networks, and national security. In this new information age, which is defined by huge amounts of data, an abundance of information does not equal power. Instead, power is the ability to use information to define reality. Thus, communication plays a central role power. Using communication to define reality requires creative thinking—something that the intelligence community (IC) struggles with. Historically, the IC has been strong when it comes to critical thinking, but the IC and the US government as a whole often struggle when it comes to creative thinking. When trying to use information to define reality it is important to remember that different cultures use social media differently. If we are going to analyze social media, we must also understand how people in different parts of the world use and understand social media.

Panel Three explored patterns of conflict and warfare in the information age. Information technologies are changing the character of warfare due to advancements in networking, robotics, command and control, etc. This panel also explored how potential US adversaries might employ information technology to create narratives that develop sympathy for their cause and hinder US involvement and decision-making during a crisis. The panel found that the information age has made the world more transparent, which consequently makes the world more lethal for US forces. The panel also concluded that the information age has made political warfare (phase 0) more relevant. Russia and China are both engaged in political warfare with the United States.

Panel Four asked representatives from the Joint Staff and Commanders to discuss how the information revolution is shaping their worlds. They found a correlation of information environment to the national security environment. Adversaries and potential adversaries to US disadvantage are using the same freedoms the USG seeks to protect in an agile manner. Information is a combat multiplier but we are moving into an age where user-generated content allows adversaries the ability to employ the ever-growing list of social media that nation-states cannot match. How do we account for this trend? The panel found that when the USG tries to do information operations, it is sprinkled into the operational plan at the very end. It has to be baked in from the beginning to be effective. Additionally, panel members found that the answers to many of the challenges we face are hidden in the data and are only seen in hindsight. We need to move the identification of key factors closer to the decision-making calculus. Finally, panel members encouraged the DOD to find creative methods to better share information with partners and allies to achieve common objectives.

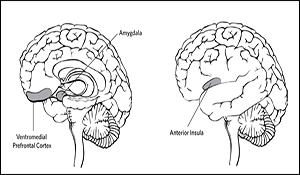

Panel Five discussed the intersections of big data, neuroscience, and national security. Big data helps allow for neuroscience insights to become operational. Linking big data to neuroscience is crucial in allowing for the use of neuroscience to provide utility in an operational environment. However, while significant advances are being made in the field of neuroscience (specifically in terms of big data collection), significant technology gaps exist. Furthermore, when operationalizing neuroscience it is important to realize there are a number of ethical and legal issues.

Panel Six examined how to understand social systems in phase 0 through human geography, big data, micro information, and the reconnaissance, surveillance, intelligence (RSI) paradigm. When analyzing a problem, it is crucial to begin by defining the purpose, perspective, and process to make the best use of available information and have effective intelligence. The distinction between what problems you are trying to solve and why it is important to you drives what kind of intelligence is needed, why it is needed, and who needs it. While data can come in various forms and provide important insights into factors like location, place, region, movement, and human-environment interaction, to actually make use of the data, it is essential that the problem set is well defined in the beginning. Data can come in many different ways, but it is important that something like metadata, leveraged crowd sourced verification, etc. is provided along with the data to illustrate trustworthiness confidence levels, etc. Furthermore, in addition to understanding confidence levels, it is important to understand that very good data can sometimes be at a scale that is inappropriate for a given analysis and if this is the case the data may not be applicable.

Panel Seven explored the implications for US influence and deterrence capability of the nearly instantaneous availability of both large and micro data. The panel used the example of attempts to deter Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) activities to begin its discussion of the impact of immediate, global communications on the effectiveness of US deterrence messages. The panel suggested that a strategic imperative for the US is to make sure that our messages, whether kinetic or informational, do not embolden or inadvertently strengthen potential adversaries. Although some argue that we need to respond quickly to opportunities to discredit or challenge adversary narratives, the USG has extremely limited capacity to change the worldviews of people in different culture and environments. There is some academic research and analysis describing countering specific adversary messages as a means of deterring unfavorable behaviors but very little that supports the notion of changing basic narratives. These research efforts need to be better operationalized for the DOD community. Furthermore, US words and deeds must be synchronized, as they are both forms of communication.

Panel Eight discussed what is in store for the Pacific Region and specifically U.S.L China relations amidst the information revolution. Over half of the world’s population resides in USPACOM’s area of responsibility (AOR), which consists of 36 nations and offers a number of unique characteristics and challenges. As two global superpowers, the U.S.-China relationship will shape the Pacific Region going forward. In order to build trust and improve security within the U.S.-China relationship and throughout the Pacific Region overall amidst the ongoing information revolution, we must understand and improve connectivity, communication/language, cultural understanding, confidence/confidentiality, collaboration, coordination, and cooperation. The information revolution has provided us with new methods of communication as well as the ability to better assess our effectiveness in our relationship with China. For the first time, we have the opportunity to fully understand communications with China. The next step will be to use communication as a means to deter and drive a specific outcome. China and the U.S. diverge on some aspects of the Internet including desired regulation levels and hacking and cyber-crime concerns and activities, all of which will influence the U.S.-China relationship going forward.

Panel Nine asked representatives from the Commands to discuss what they have learned at the conference, what they will be taking back from the conference, and where they anticipate needing further assistance. One takeaway was that the USG is not clearly messaging its own narrative. We need to focus on strengthening our own narrative in the information age. A second takeaway was the main targets of insight of many discussions were political officials. If these topics are not raised to these decision makers, we risk talking to ourselves. A third takeaway was that the information revolution is unlike other revolutions that were based on breakthrough inventions; the IT revolution continues to advance and expand. The thing we must manage is not the technology itself, but rather the evolution of that technology. A fourth takeaway is that operating in this new world requires building partnership and communities with unconventional partners within and outside of the USG. But progress in this area is impeded by an overly burdensome classification system. Finally, open source information is underutilized, particularly as non-kinetic (political) warfare become more prominent.

Leveraging Neuroscientific and Neurotechnological (NeuroS&T) Developments with Focus on Influence and Deterrence in a Networked World.

Author | Editor: Fay, T. Brig Gen (Joint Staff) & Barraza, J. (Claremont Graduate University).

This white volume focuses on possible ways that insights from the neurosciences may be incorporated into, and used within the United States Government’s (USG) approaches and ability to conduct optimized influence and deterrence operations for the purpose of maintaining global stability. In this context, neuroscientific techniques, technologies and information are viewed as viable means to build upon and enhance tactical approaches from other disciplines such as the social sciences. Understanding the neurobiology of human behavior can provide an added dimension to formulating deterrence and influence strategies in the context of a security environment that has become more complex and far more fluid over last few decades. In this white paper, the term “neurodeterrence” refers to the consideration and application of evolutionary neurobiological information about, and understanding of cognition and social behaviors that are important to deterrence theory in contexts of conflict.

Key insights provided by contributing authors that are of particular relevance to the operational community include:

- Modern deterrence must draw on multiple disciplines ranging from physics and engineering to the psychological sciences. Neuroscience and neurotechnology (neuro S/T) might well offer new insights and methods to aid military practitioners and to enhance their decision-making.

- Neurodeterrence is the application and consideration of evolutionary neurobiological bases of cognition, emotion and behaviors that are influential to individual and group aggression and violence. Such information is important to deterrence theory in contexts of understanding, predicting and mitigating/preventing conflict.

- The use of neuro S/T and the information these approaches afford can be important to the interpretation of human behaviors that do not appear to follow rational or mathematical models.

- Equally important is that while neuroscience affords great potential, it is also limited in particular aspects of technical capacity and applicability and, therefore, does not – and should not – provide a stand-alone or absolute toolkit for understanding aggression and violence. Neuroscience should be integrated into the development and evaluation of approaches to influence and deterrence.

- The field of neuroeconomics and related disciplines can provide unique insights to underlying mechanisms of human decision-making and behavior, and therefore are of importance and value to informing new developments in influence and deterrence.

- Improved understanding of the mechanisms of decision making could make important contributions toward effective deterrence. New approaches to deterrence will require consideration of the biases and motivations of decision makers as they approach complex choices. Thinking about deterrence in terms of social partners – rather than opponents – may improve the process of decision making.

- The psychology of revenge is important to explain the evolution of deterrence, which attempts to prevent aggression and overt violence prior to initiation. While characteristically considered in contexts of nuclear armament strategies, deterrence – as a concept and operational construct – predates nuclear weapons, and evolutionary models are useful to explain how deterrence emerged as an approach to individual and group actions aimed at protecting and defending people, objects, and lifestyles of value.

- There is empirical evidence that experiencing a narrative can be transformational, and can induce long-term effects upon audiences’ beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intentions and actions. Therefore, the prudent use of narratives may be a crucial approach through which to influence the beliefs of those who (are predisposed to) disagree with the position espoused in the persuasive message.

- It is important to consider not only the perspective of the person being influenced but also the potential for each actor to influence others. Preliminary evidence suggests that brain systems implicated in perspective taking and social cognition (e.g., considering ‘how might this idea be of value to others?’ or ‘what will they think of me if I share?’) may be key to understanding individual differences in being a successful idea salesperson.

- Techniques and recent research findings of social neuroscience and neuroeconomics can be useful to predict changes in individual behavior. Studies have shown, for example that neurobiological information in response to persuasive messages can provide more accurate predictions of behavior change than assessment of participants’ own attitudes toward the behavior in question and their intentions to perform the behaviors in question.

- Individual differences in sensitivity to both rewards and punishments are culturally determined to some extent, but also reflect underlying genetic-environmental interactions on a variety of levels.

- Biological events, affecting the brain, and induced by neural functions (i.e. so-called “bottom-up” and “top-down” effects), have been shown to be involved in the formation of trust. Of particular interest in this research has been the putative role of the neuropeptide oxytocin in neurobiological mechanisms of trust formation and execution. Research to date indicates that oxytocin appears to exert influence upon subliminal (i.e. preconscious) perception of social information by increasing attention given to socially-relevant interpersonal and environmental cues (thinking about the “other-in-contexts”) and by lowering sensations of (social) threat. Neuroimaging studies suggest that humans experience trust as rewarding, through activation of key mid- and forebrain networks, which may be important to functional fortification of these networks activity in various social/environmental conditions to reinforce future trust/cooperation.

- The neural phenomenon of “prediction error” can help U.S. policymakers to cause intended effects, and avoid unintended effects, on an adversary in a diplomatic or military confrontation. Prediction error provides a tool to increase or decrease the impact of our actions. A prediction error framework forecasts important effects such as inadvertent escalation; and it simplifies across existing strategic concepts so it can be operationalized without additional analytical burden. It explains historical cases and makes clear policy recommendations for doctrine and practice in China-U.S. escalation scenarios.

- The human capacity for individual and group empathy, and the behaviors fostered by these cognitive-emotional states (e.g. the extent to which altruism supersedes egoism, and empathic emotions repress self-interest) can affect attempts at deterrence in those situations when “stronger threatens weaker”. Simply put: Humans care about groups, and experience strongly emotional reaction to perceived threats to an “in-group”. Such emotionality can affect, influence (and interfere with) more rationalized decision- making relative to engaging behaviors that affect self, and “in-group” or “out-group” others.

- The intersection of new and iterative cyber-based communication technologies (CBCT) and psychological and neurobiological dimensions of behavior should be regarded as a potentially important – and viable – convergence of S/T. Possible applications and implications of such (cyber-neuro) convergence include:

- Synthesizing traditional methods of social influence with recent advances in neuroscience, cyberpsychology, and captology (the study of persuasive technology) toward development of an advanced set of personalized persuasion tactics.

- Establishment and use of chat rooms and other forms of social media to serve as digital echo chambers to effect greater social polarization.

- Novel approaches to crafting effective messages that capitalize on current neurocognitive and anthropological research about individual and group beliefs. Such research has shown that one cannot start by simply crafting a message; rather it is essential to incrementally prepare a person or an environment to make communicated messages credible.

- Combining actor-specific approaches to tailored deterrence methods within the broader neuroscience and technology (neuro S/T) framework can provide a model for operationalizable Neurodeterrence approaches.

Contributing Authors

Brig Gen Tim Fay (Joint Staff), Dr. Jorge Barraza (Claremont Graduate University), Dr. Roland Benedikter (University of California, Santa Barbara), Dr. William Casebeer (DARPA), Dr. Jeffrey Collmann (Georgetown), Dr. Nicole Cooper (Univ. of Penn), Dr. Diane DiEuliis (HHS), Dr. Emily Falk (Univ. of Penn), Dr. Kevin FitzGerald (Georgetown), Dr. James Giordano (Georgetown), Dr. Scott Heuttel (Duke), Mr. Hunter Hustus (USAF), Dr. Clark McCauley (Bryn Mawr), Dr. Rose McDermott (Brown), Dr. Ed Robbins (USAF), Dr. Victoria Romero (Charles River Analytics), Maj Jason Spitaletta (JHU/APL), Dr. Rochelle E. Tractenberg (Georgetown), Dr. Nicholas D Wright (Carnegie Endowment) Editors: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (Joint Staff), Dr. William Casebeer (DARPA), Dr. Diane DiEuliis (HHS), Dr. James Giordano (Georgetown), Dr. Nicholas D Wright (Carnegie)

Implications and Lessons Learned for Megacities.

Author | Editor: Desjardins, A. (NSI, Inc).

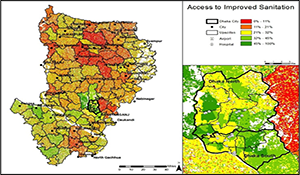

Our analysis of Dhaka shows how common problems of governance (lack of capacity, unclear lines of authority) and provision of services are magnified in both scale and impact in the context of megacities.

Although the focus of this analysis was a single megacity, our examination of Dhaka raised some issues and questions that have implications for our understanding of all megacities. Cities have been part of human society for thousands of years. Population demands continue to drive their growth while technology and innovation have helped overcome the logistical problems associated with concentrating so many people in such small areas. But is there a functional limit to the size of a city? Our analysis of Dhaka shows how common problems of governance (lack of capacity, unclear lines of authority) and provision of services are magnified in both scale and impact in the context of megacities. Environmental pressures present another challenge to the effective functioning of Dhaka. Are these problems unique to Dhaka, or megacities in the developing world, or do they also have the potential to affect all megacities?

As a town or city grows, there is a matching need to develop and manage infrastructure, planning, and provision of basic services for the population. As such systems grow in scale they tend to also grow in complexity, requiring greater expertise, technical knowledge, and resources to manage effectively. As bureaucracies become larger, they become more complex and cumbersome, potentially compromising efficiency and accountability. Governance, then, faces a dual problem: scale of task and organizational complexity. In less developed countries (LDCs) these problems have been exacerbated by the speed of growth of megacities. In many such megacities, such as Dhaka, Cairo, and Santiago, the speed of growth has far outpaced urban planning capacity and infrastructure development. This has contributed to the scale of slum developments, which become effectively ungoverned sections of the city with limited access to many basic services. In contrast, New York, Tokyo, and many of the “established” megacities in more developed countries (MDCs) did not experience the same overwhelming speed of population growth that those in the LDCs have faced. Rather they have taken their present form and scale after their national and regional governments consolidated and developed the institutional capacity to effectively govern large urban populations.

One possible solution to the problems created by the scale of megacities is to divide governance of the city into smaller organizational units, or to devolve lines of authority to the sub-city level. This could potentially increase the efficiency of service provision and general governance, both by reducing the scale of these tasks and enabling public officials to focus more specifically on the needs of various groups or geographic areas of the city. This was the approach taken in Dhaka, with the division of the city into parallel administrative entities – Dhaka South City Corporation and Dhaka North City Corporation in 2011. It appears, however, that this approach brings with it a new set of problems, specifically, overlapping areas of responsibility that increase, rather than decrease, bureaucratic inefficiency and reduces transparency and accountability. Recent reporting suggests that the division of the city may have actually further compromised service provision and heightened the chaotic governance.

When considering the governance and administrative needs of megacities several critical factors emerge. First, governing capacity and technical expertise is essential to the creation of a functioning megacity capable of meeting the needs of all of its residents. Second, the speed with which a city grows to become a megacity places increasing pressures on governance and planning; the faster a city grows, the more likely it is to outstrip the ability of any governing authority to keep up. This suggests that identifying cities that are growing at a rapid rate and intervening early to increase governing capacity and plan for future growth could relieve some of the negative (crime, environmental quality, insufficient basic services) aspects of megacities. Better understanding of the causes of rural-urban migration may also offer the potential to slow the speed of growth of some of the most vulnerable megacities, such as Dhaka. It is possible, for example, that greater investment in rural development may help stem the tide of migration to major urban centers, providing greater potential for planned development and strengthening of governing capacity as cities grow.

A Multi-disciplinary, Multi-method Approach to Leader Assessment at a Distance: The Case of Bashar al-Assad.

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. (NSI, Inc), Suedfeld, P. (University of British Columbia), Spitaletta, J. (Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Laboratory) & Morrison, B. (University of British Columbia).

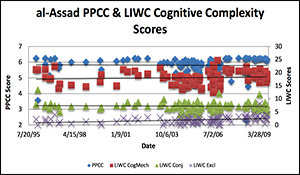

This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary discourse analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources.

The results are summarized in a two-part report. Part I (this document) provides a summary, comparison of results, and recommendations. Part II describes each analytical approach in detail.

Data: The speeches used in the study were delivered by al-Assad from Jan 2000 to Sept 2013; the past six years was sampled most densely. Additional Twitter feeds were analyzed to gauge his influence in the region.

Analytical Approaches: Five separate methods analyzed the speeches: (a) automated text analytics that profile al-Assad’s decision making style and ability to appreciate alternative viewpoints; (b) integrative complexity (IC) analysis that reveals al-Assad’s ability to appreciate others’ viewpoints and integrate them into a larger framework; (c) thematic discourse analysis of the cultural and political themes al-Assad expresses before taking action or in reaction to events; (d) qualitative interpretations of major themes in al-Assad’s rhetoric; and (e) analysis of the spread of Twitter feeds. We highlight findings that reinforce each other as particularly robust for policy.

Summary Findings: The major findings of these studies include:

- al-Assad is capable of recognizing other viewpoints and evaluates them in a nuanced and context-dependent manner

- al-Assad values logical argumentation and empirical evidence al-Assad’s integrative complexity is relatively high, but might be lower before he takes decisive action or when under intense threat

- al-Assad’s reasoning is consistent with his Arab nationalist Ba’athist political ideology, and with a consistent opposition to Israel and Western domination; al-Assad sees Arab resistance and his leadership, or at least that of the Ba’ath party, as essential

Main Findings

Basic findings from studies of al-Assad’s speeches, 2000 – 2013

- Various Measures of Cognitive Complexity: Multiple measures converge to show that Assad is capable of appreciating different viewpoints and the nuances between them. al-Assad’s integrative complexity (his ability to differentiate different perspectives and integrate them) is relatively high compared to other leaders in the region. al-Assad furthermore demonstrates an ability to be logically consistent in how he evaluates situations, and is responsive to credible (in his view) empirical evidence.

- Deterrence: Traditional deterrence theory should apply to al-Assad generally, although during periods of intense stress he may deviate more from such a model.

- Integrative Complexity (IC): In general his IC has not changed over the course of the conflict. But analysis of specific events suggests his IC tends to be lower when under intense threat, or before taking decisive and violent action, compared to afterwards.

- Arab Nationalism: al-Assad wants to lead Arab interests; he is a staunch Arab nationalist.

- Opposition to the West and Israel: al-Assad wishes to oppose Western and Israeli influence in the Arab world; the history of Middle Eastern peace talks makes Assad cynical about Israel-Palestine negotiations, despite his cognitive inclination for negotiation. Assad’s narrative of opposing Israel decreases dramatically once Syrian unrest begins (March 2011); return to this narrative may be an indicator of his baseline rhetoric in times of relative peace within Syria.

- Secular Ba’athist Political Ideology: al-Assad’s reasoning and values are consistent with a more secular, Ba’athist, political ideology.

Key Recommendations

We used the doctrinal 7-Step MISO process to characterize al-Assad as a target audience of one, and we absorbed the relevant components of our multi-method analyses into the Target Audience Analysis format. Summary of Key Recommendations along with Supporting Analyses, Part II Location, and Confidence Level are shown in table one. The main practical recommendations are:

- Avoid direct threats to the Syrian Ba’athist regime’s hold on power;

- Appeal to al-Assad’s relatively high baseline level of Cognitive Complexity (ability to see different sides to an issue, flexible decision-making, openness to information), pragmatism, and respect for Arab nationalism to broker a negotiated settlement; and

- Identify and exploit al-Assad’s dynamic levels of Integrative Complexity to assess his relative susceptibility, develop arguments and recommended psychological actions and/or refine assessment criteria at a specific point in time.

A Multi-disciplinary, Multi-method Approach to Leader Assessment at a Distance: The Case of Bashar al-Assad (Part II: Analytic Approaches).

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L. (NSI, Inc) & Suedfeld, P. et al. (University of British Columbia).

This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources.

The results are summarized in a two-part report. Part I provides a summary, comparison of results, and recommendations. Part II (this document) describes each analytical approach in detail.

Data: The speeches used in the study were delivered by al-Assad from Jan 2000 to Sept 2013; the past six years was sampled most densely. Additional Twitter feeds were analyzed to gauge his influence in the region.

Analytical Approaches: Five separate methods were used to analyze the speeches:

- Approach 1: Integrative Complexity (IC) analysis as developed by Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia) is a measure of the degree to which a source recognizes more than one aspect of an issue or more than one legitimate viewpoint on it (differentiation), and recognizes relationships among those aspects or viewpoints (integration).

- Approach 2: Thematic Discourse Analysis based on methodologies developed by National Security Innovations, Inc. (NSI) and conducted by Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne (IPFW). It provides general predictions of which themes will precede conflict and which will emerge as a reaction to conflict, an assessment of the major narratives al-Assad draws on to persuade his audiences, and analyses of themes that emerge around specific events.

- Approach 3: Automated Leadership Trait Analysis using ProfilerPlus and the Language Inventory and Word Count (LIWC) software (JHU-APL). The primary objectives were to examine (1) the cognitive complexity through means independent from the UBC method in Approach 1; and (2) al-Assad’s leadership traits using Hermann’s (2002) method of political profiling. Selections of English translations of al-Assad’s speeches were analyzed using two pieces of software: ProfilerPlus; and Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). Automated text analyses ingest and analyze the whole speech not simply randomly selected sections.

- Approach 4: Geopolitical Discourse Development Analysis. CSIS (Center for Strategic and International Studies) analyzed the common corpus of 124 speeches by Bashir al-Assad from 2000 to present. They provided qualitative interpretations of major themes that emerged in al-Assad’s discourse over the course of the 13-year period studied

- Approach 5: Analysis of Influential Arab Twitter Feeds. A team of analysts from Texas A&M University analyzed the twitter feeds of 195 influential Arabs in the Middle East, in each 24 hour period before and after al-Assad delivered a speech for the months of August and September, 2013. They also examined the relative influence of al-Assad and other regional players in the Arabic Twittersphere to determine the extent the regime is able to influence public opinion.

Major Findings: The major findings of these studies include:

- al-Assad is capable of recognizing other viewpoints and evaluates them in a nuanced and context-dependent manner

- al-Assad values logical argumentation and empirical evidence al-Assad’s integrative complexity is relatively high, but might be lower before he takes decisive action or when under intense threat

- al-Assad’s reasoning is consistent with his Arab nationalist Ba’athist political ideology, and with a consistent opposition to Israel and Western domination; al- Assad sees Arab resistance and his leadership, or at least that of the Ba’ath party, as essential.

Key Recommendations: We used the doctrinal 7-Step MISO process to characterize al-Assad as a target audience of one, and we absorbed the relevant components of our multi- method analyses into the Target Audience Analysis format. The main practical recommendations are:

- Avoid direct threats to the Syrian Ba’athist regime’s hold on power;

- Appeal to al-Assad’s relatively high baseline level of Cognitive Complexity (ability to see different sides of an issue, flexible decision-making, openness to information), pragmatism, and respect for Arab nationalism to broker a negotiated settlement; and

- Identify and exploit al-Assad’s dynamic levels of Integrative Complexity to assess his relative susceptibility, develop arguments and recommended psychological actions and/or refine assessment criteria at a specific point in time.

Main Findings

Basic findings from studies of al-Assad’s speeches, 2000 – 2013

- Various Measures of Cognitive Complexity: Multiple measures converge to show that al-Assad is capable of appreciating different viewpoints and the nuances between them. al-Assad’s baseline integrative complexity (his ability to differentiate different perspectives and integrate them) is relatively high compared to other leaders in the region. al-Assad furthermore demonstrates an ability to be logically consistent in how he evaluates situations, and is responsive to credible (in his view) empirical evidence.

- Deterrence: Traditional deterrence theory should apply to al-Assad generally, although during periods of intense stress he may deviate more from such a model.

- Integrative Complexity (IC): In general his IC has not changed over the course of the conflict. But analysis of specific events suggests his IC tends to be lower when he is under intense threat, or before taking decisive and violent action, compared to afterwards.

- Arab Nationalism: al-Assad wants to lead Arab interests; he is a staunch Arab nationalist.

- Opposition to the West and Israel: al-Assad wishes to oppose Western and Israeli influence in the Arab world; the history of Middle Eastern peace talks makes al- Assad cynical about Israel-Palestine negotiations, despite his cognitive inclination for negotiation.

- Secular Ba’athist Political Ideology: al-Assad’s reasoning and values are consistent with a more secular, Ba’athist, political ideology.

Main Recommendations:

We used the doctrinal 7-Step MISO process to characterize al-Assad as a target audience of one, and we absorbed the relevant components of our multi-method analyses into the Target Audience Analysis format. The main practical recommendations are:

- Avoid direct threats to the Syrian Ba’athist regime’s hold on power;

- Appeal to al-Assad’s relatively high baseline level of Cognitive Complexity (ability to see different sides of an issue, flexible decision-making, openness to information), pragmatism, and respect for Arab nationalism to broker a negotiated settlement; and

- Identify and exploit al-Assad’s dynamic levels of Integrative Complexity to assess his relative susceptibility, develop arguments and recommended psychological actions and/or refine assessment criteria at a specific point in time.

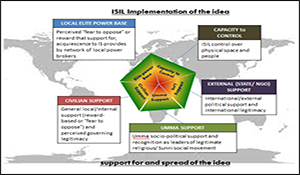

Multi-Method Assessment of ISIL.

Author | Editor: Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff) & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

SOCCENT has requested a short-term effort to assess the appeal of ISIL, specifically to answer, “What makes ISIL so magnetic, inspirational, and deeply resonant with a specific, but large, portion of the Islamic population allowing it to draw recruitment of foreign fighters, money and weapons, advocacy, general popularity, and finally support from other groups such as Boko Haram, several North African Extremist Groups, and other members of the Regional and International Sunni Extremist organizations?” A study was undertaken to understand the psychological, ideological, narrative, emotional, cultural and inspirational (“intangible”) nature of ISIL. This white paper summarizes results from analytical efforts and key results and observations.

The articles in this paper summarize work performed at the request of SOCCENT by numerous government agencies, academics, think tanks, and industry. The participants and SMEs consulted are listed in Appendix B. The work was performed over a period of four months (July-Oct, 2014). SOCCENT requested a short-term effort to assess the appeal of ISIL. Specifically, SMA2 was asked to answer the question, “What makes ISIL so magnetic, inspirational, and deeply resonant with a specific, but large, portion of the Islamic population allowing it to draw recruitment of foreign fighters, money and weapons, advocacy, general popularity, and finally support from other groups such as Boko Haram, several North African Extremist Groups, and other members of the Regional and International Sunni Extremist organizations?” The study attempted to understand the psychological, ideological, narrative, organizational, leadership, emotional, cultural and inspirational (“intangible”) nature of ISIL. The project included the development of an overall (Evolution & Longevity) framework (Section I) to synthesize the qualitative and quantitative analytical approaches for discerning the appeal of ISIL. In the process, interviews were conducted with over 50 SMEs from across the globe to gain insights into the core questions being asked (see Section II). The effort brought together different perspectives, disciplines, methodologies, and analytic approaches and sources to uncover real and apparent consistencies and inconsistencies among them and to identify how the individual pieces combine to provide a clearer picture of an issue.

Overall, there was qualified agreement on key factors explaining ISIL support—the differences are in the importance attributed to these factors by different SMEs and researchers.

On the question of ISIL longevity, the study uncovered two very different schools of thought:

- ISIL has resilient properties via its capacity to control people and territory stemming from pragmatic leadership and organization, intimidation tactics, tapping into existing Sunni grievances, use of a well-developed narrative and media outreach to attract and motivate fighters.

- ISIL is not a durable but rather an opportunistic group that 1) is taking advantage of a pre- existing sectarian conflict to acquire land, wealth, and power; 2) only attracts a narrow band of disaffected Sunni youth, 3) is alienating local populations by over-the-top violence and harsh implementation of Sharia; 4) is unable to expand into territories controlled by functioning states; and 5) does not possess the expertise required to form a bureaucracy and effectively govern.

Key insights provided that are of particular relevance to the operational community include:

- ISIL’s Capacity to Control is defined by its organizational skill and ability to use symbols, narratives, and violence (to intimidate or coerce).

- External Support – Sunni Muslim states’ main objective is power—not ideology. External support or opposition to ISIL could change rapidly based on new developments (e.g., if Shias are perceived to be winning the sectarian conflict).

- Local Elite Power Base (particularly in Iraq) is driven by elite desire to retain power and ISIL patronage, not primarily by ideology.

- Civilian Support is driven by coercion and fear, assessment of who offers better security and/or governance, and lack of viable alternative.

- Ummah Support – Radicalization is a very individualized process; there are many reasons why people sympathize, support, or join ISIL.

Key Study Observations:

- There was a significant focus in the group on the persuasive narratives ISIL uses. However, there is little evidence that the USG is well positioned to counter theses narratives, but the conditions that allowed ISIL to rise so quickly (weak states, Sunni sectarian grievances, youth bulge, unemployment, etc.) are things the USG and international community might affect over the long term.

- Beliefs about ISIL’s longevity generally fall into two camps: durable vs. flash in pan. However, a third possibility must also be considered: ISIL is a symptom of rising Islamist fundamentalism across the Muslim world combined with inequality and thwarted aspirations, declining sense of nationalism, and other pre-existing conditions including youth bulge, impact of the information revolution, drought, etc.

- The political environments and sources of acquiescence to, or support for, ISIL are different in Syria and Iraq and require more investigation. However, SMEs tended to speak about ISIL support in terms that generalized across the two. There is a danger in thinking about them the same way in terms of solutions and root causes.

Bottom line:

- ISIL exists in a very fluid context where exogenous forces can drastically alter its prospects for success, just as exogenous factors created the conditions that allowed the organization to flourish over the last two years.

- ISIL’s primacy is a relative one, due to a lack of both inspirational and pragmatic alternatives and its present coercive and intimidation tactics.

Please refer to Appendix A for an overview of the research findings presented in the report as they relate to 1) the Longevity-Evolution Framework, 2) why ISIL is so appealing, and 3) issues emerging from various workshops held in support of the SMA/SOCCENT effort.

Contributing Authors

MG Michael Nagata, US Army, Commander, SOCCENT, Director CJIATF; Ali Abbas, University of Southern California, CREATE, DHS; Scott Atran, ARTIS & University of Oxford; Bill Braniff, University of Maryland, START, DHS; Andrew Bringuel, FBI; Muayyad al-Chalabi, JHU-APL; Sarah Canna, NSI; Jocelyne Cesari, Georgetown University & Harvard University; Jacquelyn Chinn, Texas A&M; Jon Cole, University of Liverpool; Steven Corman, Arizona State University, Center for Strategic Communication, HSCB; Jonathon Cosgrove, JHU-APL; Allison AstorinoCourtois, NSI; John Crowe, University of Nebraska, START, DHS; Richard Davis, ARTIS & University of Oxford; Natalie Flora, FBI; James Giordano, Georgetown University; Craig Giorgis, Marine Corps University; Mackenzie Harms, University of Nebraska, START, DHS; Benjamin Jensen, Marine Corps University; Richard John, University of Southern California, CREATE, DHS; Randy Kluver, Texas A&M; Larry Kuznar, Indiana University–Purdue University, Fort Wayne, NSI; Gina Ligon, University of Nebraska, START, DHS; Leif Lundmark, University of Nebraska, START, DHS; Clark McCauley, Bryn Mawr College, START, DHS; William H. Moon, Department of the Air Force; Sophia Moskalenko, Bryn Mawr College, START, DHS; Dan Myers, Marine Corps University; Ryan Pereira, University of Maryland, START, DHS; Stacy Pollard, JHU-APL; Philip Potter, University of Virginia; Hammad Sheikh, ARTIS & University of Oxford; Johannes Siebert, University of Southern California, CREATE, DHS; Pete Simi, University of Nebraska, START, DHS; Lee Slusher, JHU-APL; Anne Speckhard, Georgetown University; Jason Spitaletta, USMCR, JS/J-7 and JHU/APL; Laura Steckman, Whitney, Bradley and Brown; TRADOC/G-2 Operational Environment Lab; Shalini Venturelli, American University; Jeff Weyers, University of Liverpool; Lydia Wilson, ARTIS & University of Oxford; Detlof von Winterfeldt, University of Southern California, CREATE, DHS

Socio-Cultural Analysis with the Reconnaisance, Surveillance, and Intelligence Paradigm.

Author | Editor: Ehlschlaeger, C. (ERDC).

Socio-Cultural Analysis (SCA) has evolved rapidly over the past decade as conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq have forced the DOD to reappraise the techniques used to collect information about the populations in conflict zones. As these two major con- flicts wind down, the DOD must recognize that SCA must evolve again due the changing nature of phase zero operations and prepare for future conflicts. Given the challenges of declining DOD budgets while improving our SCA capabilities, the chap- ters in this white volume describe many of the issues facing the DOD for phase zero operations and collecting the socio-cultural information necessary should conflicts escalate. Most of the chapters’ discussions were heavily influenced by LTG Flynn et al.’s “Left of bang: The value of socio-cultural analysis in today’s environment” PRISM article.1 “Left of bang…” was also revised and included in the SMA/ERDC or- ganized White Volume “National Security Challenges: Insights from Social, Neurobi- ological, and Complexity Sciences.” SMA followed that effort with additional occa- sional white papers discussing the operational relevance of the social sciences2 and social science validity,3 available at http://www.nsiteam.com/publications.html. This White Volume builds on those efforts to provide a spectrum of views on the gaps on the operational use of SCA in a phase zero setting. If there is a valid criticism to be made regarding this white volume, it is that it favors researchers attempting to automate socio-cultural information processing over traditional qualitative techniques. The authors realize that the USG must understand socio-cultural situations across the entire planet to as high or higher level of fidelity than we did in Iraq and Afghani- stan: without spending equivalent resources. Collecting magnitudes more useful in- formation with a similar or smaller budget will require innovative techniques that don’t require socio-cultural experts hand massaging ALL the data into actionable information.

The chapters are organized from the more theoretical and philosophical to the more technical. The following brief description of these papers provides an overview of each chapter, but doesn’t express all the content contained within. The final chapter is an epilogue for both this White Volume and its sister tome: “Understanding Meg- acities with the Reconnaissance, Surveillance, and Intelligence Paradigm.”

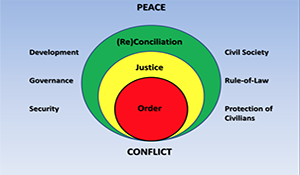

In the first chapter, “Toward a New Strategy of Peace,” Christopher Holshek and Melanie Greenberg argue that the United States Government should refocus its phase zero strategic goals to more clearly emphasize “peace and security” over our “national security.” They discuss how civil-military capabilities, partner nations, and non-government organizations can improve socio-cultural systems to make peace more resilient as part of a larger, national strategic approach.

The next chapter, “The Use of Shared Socio-cultural Information and Research Vali- dation,” discusses recent social media projects in the DoD as well as potential South Asian social media projects and the constraints likely to be seen in Bangladesh. Dr. Laura Steckman presents this view, both as a researcher and as a COCOM analyst. Chapters Eight and Eleven also focus on socio-cultural analysis using media data.

In Elizabeth Malone and Richard Moss’s Chapter Three, “Measuring Vulnerability to Climate Change: An Indicators Approach,” important natural indicators are modeled decades into the future. In a phase zero stability and security planning environment, forecasting indicators is critical to preparing plans that will take years to implement. While social indicator forecasting’s accuracy will degrade much more quickly than natural indicators, the techniques discussed in this chapter apply to modeling social indicators.

Dr. Palmer-Moloney et al.’s “Urban-Rural Dynamics and Regional Water Security” chapter presents the complex relationship between natural (water) resources, so- cial factors, state & sub-state stability, and security challenges. The chapter presents these relationships in an in-depth analysis of the Helmand River Basin.

In Chapter Five, “Through the Eyes of the Population: Establishing the SCA Baseline for RSI,” Dr. David Ellis and James Sisco expand on their earlier writings about the Reconnaissance, Surveillance, and Intelligence (RSI) paradigm. The chapter intro- duces a methodology they call the “Five Foundations of SCA.” It concludes with a case study on Syria illustrating how RSI with a rich SCA baseline using the “Five Foundations” methodology could have greatly enhanced the analysis of and policy responses to achieve US policy objectives in Syria.

Dr. Jonathan Pfautz & Mr. David Koelle, in Chapter Six “Approaches to Addressing Challenges in the Operational Use and Validation of Sociocultural Techniques, Tools, and Models” explore the challenges in creating computational models to support operational missions. They also present several approaches to ensuring operational validity of social science results.

Dr. Lynn Copeland, Lynndee Kemmet, Jeffrey Burkhalter, Marina Drigo, & Dr. Charles Ehlschlaeger discuss the potential contribution of tactical forces to strategic and operational planning in an RSI environment in Chapter Seven, “The Who, What, Where, and How of Regionally Aligned Forces: Supporting COCOM Mission Plan- ning.” While current DoD tactical phase 0 stability operations are spread throughout multiple organizations, information techniques are being standardized across these organizations. These teams are also increasingly operating within Combatant Com- mands (COCOMs) as envisioned in the Regionally Aligned Forces (RAF) concept. This chapter discusses challenges for improved data collection, the development of metrics, and phases zero information sharing.

In Chapter Eight, “Sentiment & Discourse Analysis: Theory, Extraction, and Applica- tion,” Drs. Steve Shellman, Michael Covington, and Marcia Zangrilli discuss automat- ed sentiment discourse from newly developed automated sentiment and discourse software engines. The chapter concludes with a study that uses automated infor- mation to explain and forecast the violent behavior of groups. Chapters Two and Eleven also discusses media analysis issues.

In Chapter Nine, “Integrating Social Science Knowledge into RSI,” Hargrave et al. dis- cuss a novel approach to making social science literature more easily accessible to analysts in the operational environment. The chapter includes a notional case study on the topic of insurgency in an African nation.

Chapter Ten, “Automating Early Warning of Food Security Crises,” by Dr. Molly Brown explores how a food insecurity early warning system could be automated and assessed remotely. The chapter draws from her experience working with the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS).

In “Identifying and Understanding Trust Relationships in Social Media,” Chapter Eleven, Corey Lofdahl, Jonathan Pfautz, Michael Farry, & Eli Stickgold discusses how Twitter data can be used represent four metrics that identify information-based trust relationships for potential use in phase zero planning and situation awareness. The chapter complements other media analysis research in Chapters Two & Eight.

Finally, Drs. Valerie Sitterle and Charles Ehlschlaeger will summarize the research presented in this white volume as well as the research in the Understanding Megaci- ties with the RSI Paradigm white volume as they relate to phase 0 operational de- sign and planning. This epilogue will draw heavily on “lessons learned” while per- forming research for the OSD sponsored Megacities-RSI project at ERDC.

Contributing Authors

LTG Michael T. Flynn (DIA), Dr. Molly Brown (NASA), Carey L. Baxter (ERDC), Mr. Jeffrey Burkhalter (ERDC), Dr. George W. Calfas (ERDC), Dr. Lynn Copeland (USASOC), Dr. Michael Covington (CI), Ms. Marina Drigo (PG), Dr. Charles Ehlschlaeger (ERDC), Dr. David Ellis (GBH), Mr. Michael Farry (CRA), Melanie Greenberg (AL), Dr. Michael L. Hargrave (ERDC), Christopher Holshek (AL), Ms. Lynndee Kemmet (WP), Mr. David Koelle (CRA), Dr. David A. Krooks (ERDC), Dr. Corey Lofdahl (CRA), Dr. Elizabeth L. Malone (PNNL), Dr. Dawn A. Morrison (ERDC), Richard H. Moss (PNNL), Natalie R. Myers (ERDC), Rick N. Myskey Jr. (AGC), Eric M. Nielsen (ERDC) SFC (ret), Dr. Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (ERDC & NGA), Timothy K. Perkins (ERDC), Dr. Jonathan Pfautz (CRA), Dr. Chris C. Rewerts (ERDC), Angela M. Rhodes (ERDC), Dr. Valerie B. Sitterle (GaTech), Dr. Steve Shellman (SAE), James Sisco (GBH), Dr. Monica L. Smith (NGA), Dr. Laura Steckman (WBB), Mr. Eli Stickgold (CRA), Dr. Lucy A. Whalley (ERDC), Dr. Marcia Zangrilli (SAE)