SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Understanding Megacities with the Reconnaissance, Surveillance, and Intelligence Paradigm.

Author | Editor: Ehlschlaeger, C. (ERDC).

Given the challenges of declining DOD budgets while improving our ability to monitor megacity populations, this white describe many of the issues facing the DOD for phase zero operations and collecting theinformation necessary should conflicts escalate.

The overriding goal of this White Volume is how to best understand the changing population, infrastructure, and environment in complex urban environments so that we can respond to both short‐ and long‐term national security challenges. The SMA research project “Megacity Reconnaissance, Surveillance, and Intelligence Project: Dhaka Pilot” uses the term `Megacity’ in its title to reflect the challenges of under‐ standing rapidly changing urban environments. SMA chose Dhaka, Bangladesh for the case study because Dhaka is one the quintessential urban spaces that traditional DoD socio‐cultural techniques would find most challenging to understand. Dhaka is one of the fastest growing cities in the world, a megacity with no indication that its growth rate will decline.

This White Volume explores issues relevant to understanding urban populations, both today and years from now, and the stability indicators that will help to monitor insecurity and prevent potential crises around the world. While the U.S. Government has long monitored the stability of other regimes, it does not have a long history of extensively monitoring other populations except when U.S. troops are deployed overseas. For example, the South Vietnamese military and the U.S. Army works side‐ by‐side extensively measuring and monitoring populations in rural areas prone to Vietcong activities. This very labor intensive survey was stored in a database man‐ agement system and quantitatively analyzed. It was statistically shown that the col‐ lection and use of this database reduced violence in areas with data collected com‐ pared to similar areas not monitored. Monitoring populations using human terrain teams or U.S. and Partner Nation military units, however, is both risky and labor in‐ tensive. Thus, existing population monitoring in Afghanistan and Iraq cannot be per‐ formed across the entire globe due to their costs. It is necessary to change the way we collect, integrate, and disseminate population information to achieve short‐ and long‐term national security goals.

The White Volume’s authors represent practitioners and researchers with extensive experience in their respective fields. While we were unable to include all the experts desired for this effort, the White Volume contains a broad spectrum of perspectives for better understand urban environments. The chapters are organized from the more theoretical and philosophical to the more technical. The following brief de‐ scription of these papers provides an overview of each chapter, but doesn’t express all the content contained within.

Dr. James Knotwell’s “Megacity Place‐Centric Population Analysis” begins the White Volume with a discussion on the need for cultural understanding in RSI using the “Fundamental Four” cultural descriptors. He points out the Fundamental Four doesn’t account for the “analysis of place”, or how geography affects culture. Dr. Knotwell discusses in detail how socio‐cultural analysis could be improved by better understanding of geographic analysis of place.

Next, Marc Imhoff et al.’s “Evaluating Long‐Term Threats to Environmental Security via Integrated Assessment Modeling of Changes in Climate, Population, Land Use, Energy, and Policy” chapter discusses regional environmental security forecasting energy, water scarcity, and climate changes far into the future.

In the third chapter “Understanding Megacities‐RSI – Dhaka’s Design as an Expres‐ sion of Culture & Politics,” Dr. David Ellis and James Sisco explore the socio‐cultural dynamics of Dhaka, Bangladesh from the community level, mahallas, upwards to better understand instability indicators. The chapter discusses the tension between political, religious, and social aspects of the unplanned megacity.

Douglas Batson’s chapter on land tenure and property rights in megacities discusses rural‐to‐urban migration and the piratical power grabs associated with slum for‐ mations. It examines ungoverned urban spaces and the process of building human security by improving poor peoples’ hold on land. Finally, the chapter discusses three tools that will aid in identifying and understanding who occupies and controls megacity spaces.

In the fifth chapter, “Urban Socio‐Cultural Monitoring with Passive Sensing,” Michael Farry et al. propose that passive sensors located in difficult to assess urban envi‐ ronments will provide actionable intelligence in local or tactical situations. The au‐ thors analyze how various measurable social signals can be applied to PMESII vari‐ ables. The use of small sensors, while potentially problematic if used in phase zero environments, could provide valuable information in ungoverned urban spaces when supported by partner nation governments.

While other chapters in this White Volume discuss ways to represent populations geographically or culturally, Randy Pearson’s “A Network‐based Approach to Na‐ tional Security” raises the challenges of understanding illicit financial networks. Pearson discusses the trans‐dimensionality of illicit networks, and the difficulty of representing this information for DOD operational planning. The complexity of fi‐ nancial networks is not an uncommon one for socio‐cultural analysis. Socio‐cultural systems cannot be easily represented in any of the traditional quantitative visualiza‐ tion methodologies (I.e., thematic maps, topographic maps, networks) because the number of dimensions of socio‐cultural factors is greater than what can easily be readily seen.

In Chapter Seven, “Evaluating Slum Severity from Remote Sensing Imagery,” Dr. Karen Owen discusses original research demonstrating remote sensing techniques that will help identify neighborhood‐scale socio‐cultural information in urban areas, especially economic variability. While the techniques require calibration for each megacity, the research provides excellent direction for experienced remote sensing professionals.

Chapter Eight, “Modeling the Discourse of Megacities: Assessing Remote Populations in the Non‐Western Worlds,” Dr. Kalev H. Leetaru & Dr. Charles Ehlschlaeger discuss the ramifications of collecting information from the internet in order to understand megacities. They argue that while megacities have unique geographic and social characteristics, the tools and techniques for understanding communication remain the same but that additional foundational information will ease the difficulty of monitoring urban areas in the RSI paradigm.

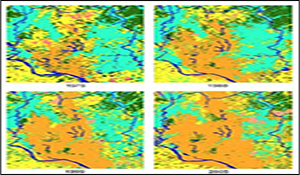

Chapter Nine, “How Semi‐Automated Analysis of Satellite Imagery Can Provide Quick Turn‐Around Economic and Environmentally Relevant Answers to Large Scale Questions”, by Ms. Ida Eslami et al., provides a technical discussion on re‐ search that can greatly benefit the RSI paradigm. The goal of their research is to de‐ velop techniques for taking satellite imagery and processing it to actionable infor‐ mation. Their technique mainly uses MODIS satellite products updated every 16 days in order to monitor changes and trends over time. Possible socio‐cultural ap‐ plications include urbanization, crop abundance & predicted yields, and the availa‐ bility of natural resources. Given the challenges of monitoring megacities around the world in phase zero, automated techniques will be necessary to derive information from the copious amounts of data collected from satellites and the internet.

The final chapter, “UrbanSim: Using Social Simulation to Train for Stability Opera‐ tions,” Ryan McAlinden et al. discuss modeling urban environments for training. Social and cultural modeling plays a critical role in advancing our situational under‐ standing of these complex, interwoven environs. Academia, government and indus‐ try all continue to make advancements in developing accurate models of human be‐ havior, though significant challenges still remain. These challenges are presented in the context of an existing training application for teaching Battalion commanders how to successfully navigate complex, multifaceted missions where the populace is the cornerstone to success.

Contributing Authors

LTG Michael T. Flynn (DIA), Mr. Douglas E. Batson (NGA), Dr. Eliza Bradley (NGA), Ms. Jill Brandenberger (PNNL), Mr. Bruce Bullock (CRA), Dr. Katherine Calvin (PNNL), Dr. Leon Clarke (PNNL), Dr. James Edmonds (PNNL), Dr. Charles R. Ehlschlaeger (ERDC), Dr. David Ellis (GBH), Ms. Ida Eslami (NGA), Mr. Michael Farry (CRA), Mr. Sean Griffin (NGA), Dr. Mohamad Hejazi (PNNL), Dr. Kathy Hibbard (PNNL), Dr. Randall Hill (USC), Dr. Marc Imhoff (PNNL), Dr. James Knotwell (KG), Mr. Kalev H. Leetaru (GU), Mr. Ryan McAlinden (USC), Dr. Karen Owen (NGA), Mr. Randy Paul Pearson (USNORTHCOM), Dr. Jonathan Pfautz (CRA), Dr. David Pynadath (USC), Mr. James Sisco (GBH), Ms. Allison Thomson (PNNL)

The ‘New’ Face of Transnational Crime Organizations (TCOs): A Geopolitical Perspective and Implications for US National Security.

Author | Editor: Riley, B. (OSD/RRTO), Kiernan, K., St. Clair, C. (Kiernan Group) & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Office of the Secretary of Defense

President Barack Obama: Significant transnational criminal organizations constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States, and I hereby declare a national emergency to deal with that threat…Criminal networks are not only expanding their operations, but they are also diversifying their activities, resulting in a convergence of transnational threats that has evolved to become more complex, volatile, and destabilizing.

Department of Defense Counternarcotics and Global Threats Strategy, 27 Apr 11: The 2011 White House Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime defines TCOs as “self- perpetuating associations who operate transnationally for the purpose of obtaining power, influence, monetary and/or commercial gains, wholly or in part by illegal means, while protecting their activities through a pattern of corruption and/ or violence, or while protecting their illegal activities through a transnational organizational structure and the exploitation of transnational commerce or communication mechanisms.”

Transnational organized crime and transnational criminal organizations refer to a network or networks structured to conduct illicit activities across international boundaries in order to obtain financial or material benefit. Transnational organized crime harms citizen safety, subverts government institutions, and can destabilize nations.

James R. Clapper, Director of National Intelligence: Transnational organized crime is an abiding threat to U.S. economic and national security interests, and we are concerned about how it might evolve in the future. We are aware of the potential for criminal service providers to play an important role in proliferating nuclear- applicable materials and facilitating terrorism.

National Intelligence Council: Five key threats to U.S. National Security: (1) Transnational Organized Crime (TOC) Penetration of State Institutions; (2) TOC Threat to the U.S. and World Economy; (3) Growing Cybercrime Threat; (4) Threatening Crime-Terror Nexus; and (5) Expansion of Drug Trafficking (Mexican drug trafficking organizations continue to expand their reach into the United States.)

Department of Defense Counternarcotics and Global Threats Strategy: Transnational organized crime represents a significant, multilayered, and asymmetric threat to our national security…It is not viable for DOD to continue to examine this complex threat through the single lens of the drug trade.

General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in an interview with NBC’s Ted Koppel on January 24th, 2013: …what we’ve had to do in response is we have become a network. To defeat a network, we’ve had to become a network…

General Stanley McChrystal, March/April 2011 edition of Foreign Policy: …to defeat a networked enemy we had to become a network ourselves. We had to figure out a way to retain our traditional capabilities of professionalism, technology, and, when needed, overwhelming force, while achieving levels of knowledge, speed, precision, and unity of effort that only a network could provide…

The continually evolving strategic environment coupled with the ascendant role of Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) necessitates a comprehensive understanding of these organizations. TCOs represent a globally networked national security threat and pose a real and present risk to the safety and security of Americans and our partners across the globe. This challenge blurs the line among U.S. institutions and far surpasses the ability of any one agency or nation to confront it. Thus, countering TCOs necessitates a whole-of-government approach and, beyond that, vibrant relationships with partner nations based on trust. These are essential if the U.S. is to remain the partner of choice and effectively counter TCOs globally. Weak and unstable government institutions coupled with scarce legitimate economic opportunities, extreme socio-economic inequities, and permissive corrupt environments are key enablers that allow TCOs to operate with impunity. These same factors enable the emergence of violent extremist organizations (VEOs). The potential nexus between VEOs and TCOs remains an area of deep concern. In this context, deeper insight into the contemporary face of TCOs will facilitate the development of strategies to counter and defeat them. This white volume examines the “new” face of these transnational crime organizations and provides a geopolitical perspective and implications for U.S. national security. The nexus of culture and technology (including modern communication technologies) and their impact on the evolution of TCOs is discussed in addition to their implications for countering TCOs.

Key Insights

- Nature of Transnational Criminal Organization (TCO) threat

- TCOs represent a globally networked national security threat and pose a real and present risk to the safety and security of Americans and our partners across the globe.

- The struggle against TCOs is a long-term proposition, requiring continuous effort, creative solutions, and the assumption of some risk.

- This challenge blurs the line among U.S. institutions and far surpasses the ability of any one agency or nation to confront it.

- The specific threats vary by region and sub-region.

- Many regions are plagued by a drug arm that is vibrant, expanding, and has both a solid supply and demand base.

- In many instances, criminal groups seem to be evolving towards a business model based on loose associations of individuals or small groups operating independently.

- Successful TCOs appear to adapt their operations to local conditions and geography.

- They utilize local resources and capabilities, outsource and enter alliances to further their interests, and rely on both local and global ethnic communities to network and operate.

- The connection of a TCO with a legal business operation lends an element of legitimacy to the group’s other activities.

- They operate legitimate businesses as front companies to help launder money associated with illegitimate activities.

- Members and senior leaders may participate in public or private political, charitable, or social events attended by highly placed political, business, and community leaders.

- They exploit legitimate commerce and, in some cases, create parallel markets.

- TCOs represent a globally networked national security threat and pose a real and present risk to the safety and security of Americans and our partners across the globe.

- Key enablers that allow TCOs to operate with impunity include

- weak and unstable government institutions that have limited reach and presence into the furthest corners of society;

- scarce legitimate economic opportunities that entice citizens to cooperate with TCOs for security and economic well-being;

- extreme socio-economic inequities that open some geopolitical regions to a much greater risk of criminal or ideological manipulation and growth than others;

- permissive environments, loose financial controls, widespread corruption, and fraudulent document facilitation networks;

- extreme interconnectedness and gaps in socio-economic and political equity creating and overall environment favorable to the formation and continued growth of TCOs; and

- globalization via Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) transforming an increasingly hyper-connected markets and economies blur boundaries and even authority across socio-political processes and State control.

- Recent analytical work based on empirical data indicates, however, that a large percentage of the countries where convergence between TCOs and VEOs is prominent are among the richest in the world. The reason for this might be that TCOs and VEOs converge in their mutual interest to create and operate in ungoverned spaces despite having different ends.

- Bottom line: The ability of TCOs to use violence or threat of violence to achieve their aims renders no one immune irrespective of governance because all system are vulnerable from a micro or individual level

- Nexus of TCOs and Terrorist Organizations

- In many war zones and in ungoverned spaces across the globe, criminal and terrorist groups have formed once-improbable relationships, finding new ways to collaborate with each other.

- Environments most conducive to the formation and support of TCOs possess the same characteristics as those favorable to VEOs.

- Organized crime not only sustains insurgencies from a financial standpoint, it also supports their asymmetric warfare campaigns.

- This VEO/TCO convergence can be tremendously corrosive and also self- reinforcing.

- On the other side of the coin, an insurgency can lose both its standing with the population and its internal sense of political identity because of criminalization. This can be exploited in a counterinsurgency campaign.

- However, not in all instances is there such a proven nexus and in many instances, the degree of overlap is difficult to determine.

- Recent analytical work based on empirical data indicates that interconnectivity is greater than one might have predicted.

- Hybrid organizations (those that include both political extremist and criminal elements) are more of a threat across threat domains (radiological/nuclear [RN] smuggling, RN smuggling with extremist organization involvement, nexus formation, and instability threat) than are the more purely criminal organizations.

- In many war zones and in ungoverned spaces across the globe, criminal and terrorist groups have formed once-improbable relationships, finding new ways to collaborate with each other.

- Top level considerations to countering and defeating TCOs

- Countering TCOs is defined as the means to detect, counter, contain, disrupt, deter, or dismantle the transnational criminal activities of state and non-state adversaries threatening U.S. and partner nation national security. This will require the following:

- dismantling their networks across the globe and driving down their impacts to levels that can be handled by local law enforcement organizations;

- fostering a transnational, cross-organizational response and development of strategic security partnerships;

- coordinating intelligence and law enforcement actions between organizations and sharing data from a variety of organizations across the globe to identify criminal networks and activities;

- developing a comprehensive Counter Threat Network approach, whole-of- government, whole-of-societies collaboration, and possibly even new structures; and

- deploying teams of globally focused financial and fraud investigators to follow the illicit money supporting TCO and insurgent networks.

- Recent analytical work based on empirical data suggests that it is difficult to disrupt the activities of the global network by targeting a few kingpins and that the most effective means of countering such a global illicit network should involve a mixture of tools used to counter criminal activity in conjunction with those used to counter terrorism.

- Whole-of-governmentapproach

- Combating Transnational Criminal Organizations (CTCO) activities are primarily interagency in nature with many authorities, capabilities, and capacities beyond the scope of DOD requiring a whole-of-government approach.

- Taking the whole-of-government approach in support of law enforcement agencies has helped build a cooperative partnership of networks to counter transnational organized crime.

- The USG needs to develop a doctrine for stabilizing territories plagued by the crime-terror nexus and putting a focus on de-conflicting the work of disparate U.S. agencies, and crafting holistic strategy.

- The USG needs to create trans-agency teams that would integrate military forces, diplomats, reconstruction and development specialists, and legal experts tasked with reestablishing the authority, legitimacy, and effectiveness of the state in a target zone.

- However, barriers remain to achieving a universal realization of TCOs as a true threat to homeland security.

- Sometimes interagency legal wrangling, sensitivities, parochialism, diminishing resources, and old-fashioned bureaucracy stymie U.S. responses.

- Specific DOD role

- DOD brings to the government unique capabilities including

- comprehensive, disciplined, and finely developed capacity to develop complex strategic plans;

- global reach as well as unique and substantial resources;

- collaborative partner capacity building;

- certain counternarcotics authorities to assist law enforcement agencies;

- capability to detect and monitor illicit trafficking and disrupt the illegal flow of precursor chemicals; and

- intelligence analysis and information sharing.

- There is, however, a lack specific knowledge of those capabilities and the processes used to obtain them within the interagency.

- Improvements in key areas are identified:

- training programs to educate DOD analysts and planners on how organized criminal groups operate and how law enforcement and other governmental groups counter organized crime;

- assigning more representatives from U.S. government agencies and organizations involved in combating organized crime to DOD organizations; and

- reviewing and streamlining authorities pertaining to DOD’s support to law enforcement as well as regulations regarding the sharing of intelligence information.

- DOD brings to the government unique capabilities including

- Role of partner nations

- Building the capacity of our partners to exercise their territorial sovereignty is crucial.

- Vibrant relationships based on trust are essential if the U.S. is to remain the partner of choice and effectively counter TCOs globally.

- Role of strategic communication in CTCO

- Strategic communication should rise to the level of main focus in many instances rather than remain a supporting effort with unachieved potential.

- Countering TCOs is defined as the means to detect, counter, contain, disrupt, deter, or dismantle the transnational criminal activities of state and non-state adversaries threatening U.S. and partner nation national security. This will require the following:

- The nexus of culture and technology in the evolution of TCOs and implications for countering CTO strategies: an evolutionary biological perspective

- The socio-technical nature of globalization is no longer treatable as separate elements.

- Current and future TCOs will be geographically and culturally dispersed.

- They will exhibit different socio-political tendencies and values.

- They will evolve different socio-technical infrastructures to support and protect their activities.

- They will mutate in response to environmental pressures ranging from market opportunities to government stability and even emergence of other criminal or VEO groups.

- Multiple and repeated interactions between system entities and individuals generate macro-level characteristics and dynamic patterns not found at the micro-level.

- They will operate as fully developed platforms for innovation that compete violently with each other and provide deviant entrepreneurs key advantages.

- The result is a strategic environment where disruptive ideas rapidly become products or processes that are tested in the real world very fast; success is easily imitated and iteratively improved.

- Modern communication technologies together with the explosion of electronically available information have

- hyper-connected markets and societies across the globe;

- enabled expansion of TCOs into emerging markets; and

- allowed TCOs to rapidly recruit expertise and employ various skills on a temporary or transient basis without the need to formally augment their enterprise. (Similarly, VEOs may recruit and sway sympathetic individuals without relying on old methods of radicalization or complete indoctrination to the cause.)

- Technological breakthroughs and their impact

- Advances in additive manufacturing, online anonymity, anonymizable currencies, and communication technologies amongst others have the potential to change the contours of the landscape entirely.

- They increase the potential for violent upheaval and instability because they empower greater numbers of individuals

- Modern communication technologies make it much more difficult for law enforcement to monitor and/or trace communications and financial flows among nodes in the networks.

- Implications for countering TCOs

- Deviant innovators have one essential business requirement: to be one step ahead of the governmental deployment of interdiction technologies to remain a profitable operation while being ready to hack new inventions as soon as they are deployed.

- This necessitates that governments respond accordingly

- The USG should constantly play the role of TCOs, penetrating governmental technologies.

- Policies should be designed in a way that whenever the environment changes, the shape of the governmental response can change with it.

- Think at the scale of big technology trends, devaluing the importance of any individual adaptation in any threat assessment.

- Cyberspace offers a solution in terms of collaboration environment providing CTCO groups a data ecosystem that is fluid enough to let organizations innovate from the bottom up in response to local conditions. On the other hand, balancing competing needs for security and access provide scaffolding for an entire range of cyber-enhanced capabilities. This three-element structure allows coordination and collaboration in local spaces, as well as global data sharing.

- A better fundamental characterization of the cyber-socio-technical nexus can help form cogent U.S. defense-related policies and guidance for operational context.

- The socio-technical nature of globalization is no longer treatable as separate elements.

Contributing Authors

Mr. Gary Ackerman (START); Maj David Blair (USAF/Georgetown University); Ms. Lauren Burns (IDA); Col Glen Butler (USNORTHCOM); Dr. Hriar Cabayan (OSD); Dr. Regan Damron (USEUCOM); Mr. Joseph D. Keefe (IDA); Col Tracy King (USMC); Mr. David Hallstrom (JIATF West); Dr. Scott Helfstein (CTC); Mr. Dave Hulsey (USSOCOM); Mr. Chris Isham (JIATF West); Ms. Mila Johns (START); Mr. James H. Kurtz (IDA); Dr. Daniel J. Mabrey (University of New Haven); Dr. Vesna Markovic (University of New Haven); MG Michael Nagata (Army, J-37); Dr. Rodrigo Nieto-Gomez (NPS); Ms. Renee Novakoff (USSOUTHCOM); Ms. McKenzie O’Brien (START); Dr. Amy Pate (START); Ms. Gretchen Peters (George Mason University/Booz Allen Hamilton); Mr. Christopher S. Ploszaj (IDA); BG Mark Scraba (USEUCOM); Mr. William B. Simpkins (IDA); Dr. Valerie B. Sitterle (GTRI); Mr. Todd Trumpold, (USEUCOM); Mr. Richard H. Ward (University of New Haven); Mr. Tom Wood (JIATF West); Dr. Mary Zalesny, (CSA SSG, PNNL)

7th Annual SMA Conference: Over a Decade into the 21st Century…What Now? What Next?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The 7th Annual Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Conference was held at Joint Base Andrews from 13-14 November 2013. The conference was focused on global megatrends and their implications in all spheres of national security. It is no exaggeration to state that the world today is a very different place than it was barely 12 years ago when the war against al Qaida and its affiliates began. As we move forward, continuing advances in various spheres such as the sociotechnical world will present both challenges and opportunities. The conference examined these and related themes and highlighted new insights from the social and neurosciences.

As in previous years, the conference addressed the needs of the Geographical Commands. Representatives from the Commands discussed their pressing needs and key operational requirements so that SMA’s wide network of experts could assist in identifying capabilities that match these needs.

Findings from Panel Discussions

Guest speaker Brig. Gen. David B. Béen, Deputy Director, Special Actions and Operations, J-3, spoke about the unique ability of SMA to bring together representatives from a diverse community—including from the DOD, academia, industry, media, etc.—to address core requirements of the Combatant Commands (COCOMS). This community can help the DOD succeed in its main duties: 1) being mindful of future threats to the United States and 2) exploiting emerging opportunities to make the world a more stable place. The DOD has a responsibility to engage in rigorous analysis, informed debate, and top-flight research with partners. Members of the SMA support community also bear certain responsibility to build relationships, learn more about operational needs, and apply their considerable talent to help operators achieve mission success.

Guest speaker Mr. Earl Wyatt, Rapid Fielding Office, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, spoke about the need to bring various resources from across the government, industry, and academia to bear on DOD’s objectives. The force of the future will be leaner, more agile, more flexible, and technologically advanced. While U.S. forces will be called on to do more with less, this is not a down time for innovation; it is a challenge to do more with less. The DOD will be particularly challenged to engage in innovative thinking to mitigate threats in nonkinetic ways. Partner capacity will be key to this conversation. The DOD is moving toward a more balanced prototyping portfolio to include developmental as well as operational prototyping to provide a hedge against technical uncertainty or unanticipated threats; enhance interoperability and reduce lifecycle costs; and explore the realm of the possible without commitment of follow-on procurement.

Guest speaker Mr. Ben Riley, Rapid Fielding Office, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, spoke about the value SMA provides to the DOD by bringing together a diverse group of academic and technical perspectives on difficult problems. However, the DOD still needs to open its aperture more widely to encounter new ideas and perspectives. In a time of resource constraint, there is a tendency to circle the wagons around traditional defense programs, but it is important to continue to engage in rigorous, innovative, and unexpected thinking to meet the commanders’ needs.

Keynote speaker, LTG Michael Flynn, Director, DIA, spoke about accelerating change in the defense intelligence community. The two big challenges facing the defense intelligence community are skyrocketing demand and resource reduction. In order to meet the two challenges, the DIA needs to restructure and adapt. The DIA needs a new model to prepare the foundation that provides U.S. forces with agility, flexibility, and resiliency. The USG must be prepared for unknown, highly complex, uncertain environments. One failure of the last decade has been our limited ability to understand the operational environment, which led to mismatch in resources and capabilities. This failure needs correction in order to meet the challenges of tomorrow.

Panel One discussed the use of religious engagement by the United States to improve global prospects for peace. It is important that the USG engages the full realm of social actors when trying to understand operational environments. Within this group, religious leaders are some of the most influential actors—specifically in Muslim communities. In many cases, religious leaders are more credible than the highest-ranking political officials in that community are. U.S. organizations like the Special Envoy to the OIC have committed to religious engagement in areas including healthcare, maternal health campaigns, religious freedoms, and countering violent extremism. The panel agreed that the commitment by the United States to continued religious engagement in these areas and beyond is crucial. Furthermore, the United States must ensure that its religious engagement efforts are viewed as legitimate by the local communities in the places where the religious engagement is taking place.

Panel Two discussed four significant megatrends likely to emerge in the next decade: demographic change, resource stress, further diffusion of power, and individual empowerment. There are two particularly relevant projections that support the diffusion of power megatrend: 1) by 2030, Asia will have surpassed the United States and Europe in power and size while Europe, Japan, and Russia continue to decline, and 2) by 2030, the international system will transition from hegemony to multi-polarity. With regard to the resource stress megatrend, competition and scarcity involving natural resources are emerging as security threats for the United States and its allies. U.S. allies are particularly vulnerable to natural resource shock. The perfect storm involves youth bulge, unemployment, ability to organization through information technology, and a food shock. Furthermore, the convergence of multiple trends means individuals and groups are angrier and more dangerous. With regard to demographics, the most relevant finding for the USG is that the ratio between young adults and older adults in some of the world’s most unstable regions is declining, which statistically suggests greater stability and democracy in the coming decades. However, some of the countries that the USG is, or has been, most involved in still have high fertility rates and very youthful populations.

Panel Three examined the current era and why it is special. First, it has produced an increasing number of mega-issues. Mega-issues are not simply larger public policy issues; they are significantly different from issues of the past. There are two primary mega-issues facing the current era: mega-disasters and megacities. The mega-issues of today are challenging because the currently existing policy is not designed to deal with this magnitude of challenge. Furthermore, other issues facing the current era—such as under-development, ethnic diversity, regime stability, etc.—can only be addressed through collective action and a global perspective. However, this is quite difficult because many of these issues are viewed differently throughout the world. Finally, it is important to be careful when trying to compare different eras in different times. Analysts today are likely biased in thinking that the current era is unique because they are living in it. This era may be unique, but it is not

Panel Four reviewed the role of social sciences in national security as well as validation and validity concepts. Understanding and utilization of social sciences is critical for DOD operations in the 21st century. Social science uses theory to understand intentions and to explain causal links between actions and outcomes. We need an entire spectrum of social science disciplines (economics, sociology, communications, history, etc.) to understand complex problems. From an operational viewpoint, a set of validated social science theories are a good foundation for building a framework capable of informing decision-making. However, social science theories are often not validated for specific military decision- making processes. Thus, it is dangerous for operators to treat a discipline’s theories as fact without first consulting with scientists familiar with the limits of those theories. There is a mismatch between the defense and social science culture. One necessary way to bridge the divide is to train and develop a cadre of military social scientists.

The Feedback from Commands Panel provided an opportunity for representatives from the commands to discuss their pressing needs and key operational requirements. First, all of the commands emphasized the need for greater cooperation within the DOD as well as the whole of government. Building relationships with non-traditional and non-government entities, like those attending the SMA conference today, are increasingly important in a resource constrained environment. USNORTHCOM identified countering threat networks as its primary operational focus. Therefore, it is imperative for DOD to invest in interagency collaboration and provide support to law enforcement partners in combating transnational organized crime. This will provide for a better understanding complex, transdimensional networks. PACOM has the most diverse portfolio of all of the COCOMs; therefore, its requirements range from nuclear deterrence, counterterrorism, geo-political stability, transnational crime, natural disaster response, cyber security, and human trafficking. PACOM’s chief objective is to stay in steady state operations while strengthening relationships with countries in its area of responsibility (AOR). AFRICOM faces multiple challenges as well including terrorism, weak governance, natural resource management, illicit trafficking, humanitarian assistance, training, border security, maritime security, and defense institution building. AFRICOM relies on soft levers of power to address many of these issues. CENTCOM is facing new threats (threat financing, supporting rule of law, etc.) that traditional military forces have not had to face. These threats require a multi-layered solution that relies on cooperation, liaison, and engagement with non-traditional partners. SOCOM’s challenges include an uncertain future, volatile trends, redistribution of power, and the increasing role of non-state actors (NSAs) and transnational criminal organizations (TCOs). Other threatening trends include youth bulges, shifting demographics, and urbanization. Globalization and accelerated change place pressure of the system making the scale of the problem worse. SOCOM will meet its challenges by strengthening its global soft power network. This means increasing the capacity of allies, partners, and the interagency community to respond to the world’s problems. SOUTHCOM’s mission sets include counternarcotics trafficking, counter TCO, and disaster response. SOUTHCOM has always operated with resource constraints. It has developed strong interagency partnerships to compensate.

Panel Five discussed the “new” face of transnational criminal organizations (TCOs). The continually evolving strategic environment, coupled with the ascendant role of TCOs, necessitates a comprehensive understanding of these organizations. TCOs represent a globally networked national security threat and pose a real and present risk to the safety and security of Americans and their partners across the globe. The TCOs of today are profit driven organizations. One of the key challenges in combatting TCOs is to identify the illicit networks and finance organizations that are the oxygen of a TCO. TCOs are sophisticated organizations that are constantly evolving and trying to combat them is becoming more difficult. Often times, legislation does not keep up with the sophistication and evolution of these TCOs and their tactics. It is imperative that legislation continues to evolve as the TCOs become more sophisticated. Furthermore, when combatting TCOs, it is essential that a collaboration effort exist between the defense, intelligence, law enforcement, and other interagency partners. The United States must continue to build the capacity and capabilities of its partners and the interagency community in combatting the TCO threat.

Invited speaker Brig Gen Timothy Fay, JS/J33, noted that during the Feedback from COCOMs panel, none of the representatives mentioned nuclear deterrence, yet it is one area where the DOD needs SMA’s help. One of the biggest challenges of nuclear deterrence is the lack of articulate, informed, rigorous discussion and research. For example, little effort has been applied to understanding the illicit networks that built many of today’s nuclear programs such as that of Pakistan and North Korea. Urban legends—such as that the United States no longer needs or uses its nuclear arsenal—continue to drive the debate. Strategic weapons are made for deterrence, not deployment. We use these weapons every day. They are effective and a part of our adversary’s decision calculus. Another challenge facing the DOD today is how to further adapt policy and strategy in alignment with a smaller arsenal and a more uncertain world environment. SMA has done some great work to contribute to this conversation, but there is a lot more that needs to be done.

Panel Six discussed the sociotechnical world and its new era of disruption and opportunities for innovation. The rapid and continual coevolution of the social and technological sectors is creating a globally pervasive sociotechnical ecosystem. The current security problems facing the United States are social change problems. As a result, it is crucial to understand the full social realm—narratives, networks, interests, identities, vocabularies, desires, and disgusts. Cultural dynamics drive the evolution of technologies as much as the actual technological problem. Connectedness is a new dynamic that is crucial and underpins the current era. Connectedness is what makes mega-issues and mega-events possible. When talking about the framing of problems on a global scale, it is the awareness of the problem that makes it mega, and connectedness increases overall awareness. The operational environment is constantly evolving. The question becomes, how does the United States operate in this changing environment, and what does this change mean for stability? Stability needs to be defined as the ability to adapt to a changing situation. The new status quo is that there is no status quo.

Invited speaker, Lieutenant General Robert E. Schmidle, Jr., USMC, spoke about the intersection of national security and universal principles. He argued that universal principles do not exist; context matters. Some saying the admonition not to kill is a universal principle, but killing to defend oneself is permissible. He further argued that the assumption that rationality guides decision-making is also flawed; man can reason his way through anything. Instead, people rely on hinge beliefs—practices that define a culture. Not knowing or understanding a partner’s or adversary’s hinge beliefs puts one at a disadvantage from the beginning. The search for universal principles is debilitating to our ability to come up with a coherent national security strategy.

Panel Seven examined the importance of understanding megacities in the 21st century. Megacities are rapidly growing and changing population centers where urbanization often far outstrips the ability of governments to enforce rule of law and provide basic socio- economic services such as clean water, sanitation, etc. As a consequence of these deficiencies, these densely populated urban areas can become spawning grounds for public resentment, criminal activity, and political radicalization, which is a national security concern for U.S. policymakers. Understanding megacities is crucial. Urban areas are the key terrain of the future. Developing world megacities thus far have been surprisingly resilient, but the potential for a natural disaster or threat to sovereignty from a non-state actor loom. Megacities are new phenomena and must be understood for future U.S. defense and diplomacy actions. A significant challenge to understanding megacities is the sheer amount of data that is involved in the process of understanding, making interagency collaboration and information sharing key. A method for making sense of all of this data and visualizing it clearly needs to be created. There is a need for a planning support framework for understanding megacities—a model that marries the benefits of rigorous critical thinking with the applied setting in which planners and operators work. A method needs to be developed for fusing these two aspects together to produce a more holistic understanding of megacities.

Panel Eight explored long- and short-term regional and sub-regional stability in South Asia and the Western Pacific region. Panelists argued that the division of South Asia into two COCOM AORs makes it difficult for analysts and planners to address transboundary concerns. Furthermore, analysis must take place at the regional or sub-regional level. India is a rising power, but it is cautious not to be seen as a counterbalance to China. India wants regional balance, participation in the region’s strategic dialogue, and translation of dialogue into actual cooperation. Countries in Asia are concerned about what the future presence of the USG in the region will be given budgetary constraints and China’s aggressiveness in the South China Sea. Countries in Asia will still look to the United States for security, but they will also begin diversifying.

Panel Nine discussed neuroscience and its implications for national security operations. The Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative is a new research effort started by President Obama to revolutionize the understanding of the human brain by accelerating the development and application of innovative technologies. Approximately $100 million will be invested for scientific research during FY 2014 as part of the BRAIN initiative, which will be led by the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The study of the brain is important because it is the wellspring of human behavior. In the national security domain, especially, there should be an interest in understanding the brain because it is part of the ecology that drives human behavior that is important to national security. Neuroscience allows us to access and engage the brain. This insight into the brain is beneficial for the healthcare, public life, global relations, and public defense realms. It is clear that neuroscience represents a viable science and technology pursuit for the next 10 to 20 years. Areas for growth that need to be developed over this timeframe with respect to understanding the brain include improving the understanding of how the brain recognizes problems, influences culture, and functions in groups.

In conclusion, LTC Matthew Yandura thanked the panelists, moderators, and conference attendees for another successful SMA annual conference. He encouraged participants to build on relationships formed during this conference. There has to be value in relationships or conferences like this go away. The military community should remember that they are not just recipients of this scholarship and research; they are part of the community in service of this nation.

Humans in the Loop: Validation and Validity Concepts in the Social Sciences in the Context of Applied and Operational Settings.

Author | Editor: Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff), Ehlschlaeger, C. (ERDC), McGee, A. (Naval Postgraduate School) & Ackerman, G. (University of Maryland, START).

Threats in the 21st century are increasingly complex, requiring multiple perspectives and disciplines to understand and anticipate challenges. National security issues will require consideration of the insights that might be gained through social science analysis in order to provide broader understanding of both challenges and potential solutions. Many of the challenges and potential missions faced by the Department of Defense (DOD) will be multi-faceted in their most fundamental nature. To better understand these issues, their origins, and potential solutions, we need to think clearly about insights provided about the psychological and social dynamics impacting complex security problems. We can anticipate military operations and missions in a networked, dynamic global environment where modern media, the pace of technological change, and speed of events overlay often long standing historic social legacies and conflicts. We can turn to the social sciences to better understand the intersection of new technologies and legacies and, therefore, assist in crafting strategies to deal with current and emerging issues.

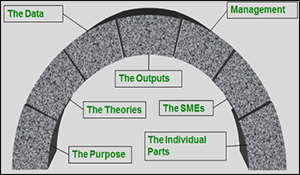

This white paper discusses the validity concepts and validation of the social sciences in the context of applied and operational settings. It focuses on a key issue: How do we gauge the degree to which our frameworks, models, and measures of human social behaviors correspond to the real issues with which DOD operators are concerned? It addresses these issues from several perspectives:

- Scientific Validation in Social Science: What concepts are appropriate for assessing the “goodness” of the social science within the scope of DOD missions?

- Determining Mission Applicability: Social sciences play roles at various phases of military planning. Will these necessitate varying degrees of validation?

- The need to develop military social scientists to bridge the gap between social sciences as an academic discipline and their potential applications in strategic, operational, and tactical decision making.

Whether planning how to help train and develop a military unit, motivate an individual from another culture to participate in an activity, deter a nation-state from a course of action, stabilize a village, or persuade individuals to reject an extremist group, analytical efforts require thinking about the fundamental dynamics of people, groups, and societies. As a result, analysts, planners, and operators need to become more informed and active consumers of social science knowledge. This white paper is aimed at both motivating readers to confront that challenge and at providing some basic insights to reduce the scope of the challenge. Greater engagement with both the body of social science knowledge, and with the process of social science itself, has the potential to increase DOD effectiveness in an increasingly complex, less predictable, more connected, and more problematic world.

Use of the social science techniques in the DOD has a long pedigree. Yet the challenge remains over how to best leverage social science tools to support military operations.

Challenges in assessing reliability and validity of social science tools, techniques, and models, especially those developed for use in Information Operations, include the following.

- Human and social science fields typically lack theoretical maturity as compared with the physical sciences. This challenges the accuracy or representation and the expertise of users.

- Human social behavior often reflects a rich and complex problem space. This challenges the realism of the representation.

- Human social behavior involves many unobservable phenomena. This challenges the expertise of subject matter experts and the credibility of the model to users.

- Both psychological awareness and human behavior involve socially constructed factors and variables. This challenges the accuracy and realism of the representation.

- Consistency in assumptions related to a model’s purpose when reusing scientific statements/theories that are encapsulated in software is essential.

Essentially, validation is about what works and what does not. At the operational level, people want workable tools to current problems. In this context, a “validated” theory has to be relevant to the operations community.

In addition, the white paper highlights the need for a cadre of military social scientists that understand both the academic and operational environments and act as a bridge between these two now very different environments. These individuals should be able to elicit user requirements and then employ their domain knowledge to satisfy those requirements. Therefore, there is a need develop a strategy as to how to best provide a focused, comprehensive, and integrated social science training program for officers and enlisted that spans their entire career.

The past decade of combat has once again brought the “human domain” of warfare front and center. The classic geographic factors of physical, cultural, economic, and political have demanded attention from the strategic to tactical level of range of military operations. Operational requirements have historically inspired innovation in organizations and diversification in cross-sector collaboration. This legacy can be used as a foundation for the growth of “military social science.”

The essential concern of the social sciences is human behavior. The classic disciplines (e.g., economics, political science, sociology, anthropology, etc.) loosely align with the levels— individual, group, societal—and the subjects of those behaviors. What social scientists do is attempt to describe and explain the influences and interactions among complex sets of factors that span human behaviors. This white paper continues the SMA White Paper series, The Role of the Social Sciences in DOD Mission Analysis and Planning, with a discussion of validity concepts and validation in the context of applied and operational settings. In so doing, it focuses on a key issue, namely: How do we gauge the degree to which our frameworks, models, and measures of human social behavior correspond to the real issues with which DOD operators are concerned?

Contributing Authors

Mr. Gary Ackerman (START, Univ. of MD); Mr. Ricardo Arias (SOUTHCOM); Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI); Lt Col Alexander Barelka (USAF AFMC); Mr. David Browne (PACOM); Dr. Charles Ehlschlaeger (ERDC); Dr. Dana Eyre (SoSA); Ms. Laurie Fenstermacher (AFRL); Mr. Ben Jordan (TRADOC/G-2); Dr. Anne McGee (NPS); Ms. Jane Peplaw (SOUTHCOM); Mr. Eric Ruenes (DIA); Dr. Laura Steckman (PACOM); Dr. Ivan Welch (TRADOC/G-2) Editors: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (JS/J39); Dr. Charles Ehlschlaeger (ERDC); Dr. Anne McGee (NPS); Mr. Gary Ackerman (START, Univ. of MD)

Operational Relevance of Behavioral & Social Science to DOD Missions.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

This paper emerged from the “A World in Transformation: Challenges and Opportunities” Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) Conference in November 2012.2 Leaders from across the USG addressed the emerging challenges of the 21st century for defense analysts, planners, and operators. The first decade of the 21st century has ushered in a period of rapid change across the globe: demographic upheavals are challenging the status quo, classic nation states are in decline, and people are more interconnected than ever. Panelists agreed that in this uncertain environment, the social sciences3 play an ever-expanding role. Thought leaders from across the defense community discuss the relevance of social science to DOD operations in this section.

Building Frameworks to Inform Whole of Government Response

Maj. Gen. John “Jack” Shanahan, Deputy Director for Global Operations, Operations Directorate, Joint Staff

A paradigm shift is occurring across the globe. We do not yet know how the world will look when this shift is completed, though it is already being characterized within the Interagency as the “new normal.” We must consider two paradigms. First, adversaries and potential adversaries—often grouped under the rubric of Violent Extremist Organizations, or VEOs,– are becoming syndicated in ways we did not fully anticipate or appreciate a decade ago. We are witnessing a rising trajectory of communication, collaboration, and sharing of ideas, weapons, lessons learned, and tactics among disparate VEOs that once seemed to have very few common interests or goals—or even if they did, they were unable to join forces in ways that represented a more significant threat than they did in isolation. VEO cooperation, coordination, and synchronization are enabled by the explosion of social media and almost- instant global communications. At the same time, we are not keeping up with this VEO paradigm shift; when we do, it is often in a predominantly tactical and reactive manner. In short, our adversaries and potential adversaries are more rapidly and effectively shifting paradigms than we are.

There is an unmistakable ideological component to this paradigm shift. We are in danger of losing the strategic narrative, the so-called ‘battle for ideas.’ Our adversaries and potential adversaries are engaged as never before in a competition for the ideological high ground. Distorted ideas and ideals that were easily brushed aside twenty years ago are finding an unprecedented audience and gaining a dangerous foothold in the ungoverned spaces of the science can and must play a central role in both understanding and competing against the VEO ideology. In today’s information environment, the Internet and social media are among the most potent weapons in the VEO arsenal. We must engage readily and continuously in this electronic battlespace or we will lose the clash of ideas.

Federal agencies are working to respond to a broad spectrum of complex social threats facing the United States in the 21st century including radicalization, cyber radicalization, instability, and insurgency, but there is no uniformity of approach. The social sciences can provide a rigorous framework to explain these phenomena and to guide research, analysis, and operations. Social science knowledge, methodologies, and models inform the commanders so that conflict stays left of boom. However, further research is needed and operators need to better understand the role and potential of social science to inform decision-making and to ensure our paradigm shift is as substantial and as enduring as that of the VEOs.

Responding to Emerging Threats

Mr. Earl Wyatt, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, Rapid Fielding in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research & Engineering

One of the Rapid Fielding Directorate’s (RFD) missions is to respond to emerging threats by identifying, developing, demonstrating, assessing, and rapidly fielding innovative concepts and technologies to meet operational needs. The social sciences are uniquely positioned to contribute knowledge, tools, and models to address some of the most pressing questions facing operators and decision makers today including:

- How do we best anticipate and disrupt the triggers of violent actions?

- How do we prepare for the unintended consequences that may result from U.S. engagement?

- How do we communicate U.S. intentions and foster trust in a country with decentralized government?

- How can we defuse the need for kinetic engagement and measure the success of these efforts?

- How do we best strengthen and measure the benefits of building partner capacity?

To address these questions, we need social science models capable of scaling up or down to address a wide range of divergent threats. This is critical to establishing a leaner, more agile force to effectively operate across all domains. It is imperative that the delivery of these technical capabilities is accelerated to win the current fight.

Multidisciplinary Responses to Complex Challenges

Mr. Ben Riley, Principal Deputy, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Rapid Fielding in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, Research and Engineering

Threats in the 21st century are increasingly complex and require multiple perspectives and disciplines to understand and anticipate challenges. No longer can the DOD rely solely on subject matter experts to understand and engage with populations. The social sciences need to be deployed at the tactical level. Social science insights, theories, and models give the commander the kind of information that is critical for him to achieve his mission in complex environments. However, it is not enough to employ social science tools and methods in the operational environment. The tools require the intellectual curiosity of the commander in the fields. The community needs to concurrently invest in training officers how to employ social science tools and methods.

The Changing Role of Social Sciences in the DOD

Dr. Robie Samanta Roy, Professional Staff Member, Senate Armed Services Committee

The changing nature of warfare emphasizes the need to develop a deeper understanding of the human perspective. Conflict is emerging in diverse corners of the world, and the DOD needs to develop the expertise in each of these regions. Social science initiatives are crucial for understanding this human terrain.

However, investment in the social sciences faces a few obstacles. First, the gap between the research and user communities needs to be bridged and narrowed. Second, coordination within the research community needs to be improved to eliminate redundancy, focus on meeting warfighter needs, and quickly transition from basic to applied research. Third, the emphasis on multidisciplinary approaches must be maintained and further developed including bringing together experts from across a broad spectrum of disciplines. Fourth, the community needs to do a better job of developing measures of effectiveness (MOE) to understand the impact of operations on communities of interest. Finally, the community needs to address the verification and validation of high quality data, models, and theories.

It is necessary to shape the future direction of social science programs now. This shaping will include the training of future experts to ensure that these efforts are sustainable. Additionally, through increases in international cooperation, greater insight on “the other” will be gained. Furthermore, research into the role of political and religious ideologies needs to be pursued. Finally, the convergence of behavioral science and neurobiology will help inform future challenges including how best to respond to adversaries that do not have the same ethical constraints that the U.S. does.

Contributing Authors

Maj. Gen. John Shanahan (Joint Staff), Mr. Earl Wyatt (RFD/ASD R&E), Mr. Ben Riley (RFD/ASD R&E), Dr. Robie Samanta Roy (SASC), Hriar Cabayan (SMA OSD), David Adesnik (IDA), Chandler Armstrong (USACE ERDC), Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI), Lt Col Alexander Barelka (USAF AFMC), Thomas Bozada (USACE ERDC), David Browne (PACOM), Charles Ehlschlaeger (USACE ERDC), Dana Eyre (SoSa), LTG Michael Flynn (DIA), LTC John Ferrell (SOUTHCOM), LeAnne Howard (SOCOM J5), Robert Jones (SOCOM J5), David Krooks (USACE ERDC), Anne McGee (NPS), Timothy Perkins (USACE ERDC), Dan Plafcan (OUSDI), Lucy Whalley (USACE ERDC)

Insights from Neurobiology & Neuropsychology on Influence and Extremism—An Operational Perspective.

Author | Editor: Reynolds, M. (Joint Staff) & Lyle, D. (USAF).

This report provides the operational and policy communities with a deeper understanding of the unique behavioral and neurobiological factors that underlie political extremism enhanced by interaction in the cyber realm. It addresses the implications of advances in neurobiology and neuropsychology for the way we plan and execute military operations as part of a comprehensive approach to counter violent extremists and the spread of their violent political narratives. The paper focuses on the intersection of emerging cyber technologies and human biology including of both psychological and neurobiological dimensions of behavior. For the purposes of this white paper, we will refer to these two dimensions as cyberpsychology and cyberneurobiology respectively.

Key Insights

- Modern information technology is empowering violent extremist organizations (VEOs) by providing cheap and anonymous forums to target large audiences. Advances in Cyber- Based Communication Technology (CBCT) will revolutionize how the DOD operates in cyberspace and will heighten challenges to Military Information Support Operations or MISO (formerly psychological operations or PSYOP).

- The next twenty years will see a paradigm shift in the fundamental character of the Internet that will revolutionize how people interact globally. Changes include

- the shift from Internet Protocol version four (IPv4) to Internet Protocol version six (IPv6) and the emergence of the Next Generation Internet;

- alternative Domain Name Systems;

- generic top-level and internationalized domain names;

- Broadband mobility;

- Cloud computing and big data;

- Ubiquitous computing; and

- IPTV (a technology that allows for broadcast of audio-video material).

- Bottom line: The impending changes will add additional challenges to the ability of MISO and cyber operations to influence perceptions.

- The next twenty years will see a paradigm shift in the fundamental character of the Internet that will revolutionize how people interact globally. Changes include

- Communication technologies are means, not ends—they shape social worlds by connecting people in distinct ways, but it is the social world itself that creates outcomes.

- Deemphasizing the distinction between mass media and social media facilitates more fruitful exploration of the social implications of different means of communication.

- A four-way communication typology (i.e., speed, directionality, span, and configuration) allows exploration of the human terrain.

- CBCT can blur the lines between physical reality and cyber-formed reality, which may differ in delivering catalysts for extremist action while potentially removing vital inhibitors.

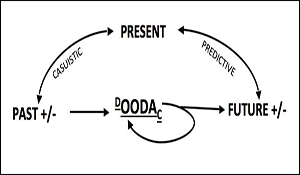

- CBCT likely does not contribute to radicalization and mobilization to political extremism in a linear fashion. Rather, the various modes of CBCT interact with shaping factors (i.e., culture, values, genetic background, access to technology, etc…) and transition factors (i.e., activators, catalysts, inhibitors, and interventions) to produce psychological and behavioral outcomes.

- Only a very small subset of individuals becomes more radical in their thinking or mobilizes due to interactions with CBCT.

- The impact of CBCT on a person is dependent on the individual’s motivation for using the medium.

- Bottom line: CBCT often provides isolated individuals the informational equivalent of an echo chamber through which they can actively or passively access information that is consistently biased toward already expressed preferences and, thus, reinforces and strengthens their existing worldviews and limits the probability of their encountering information that is potentially contradictory or disconfirming. Tailored search algorithms and the psychologically rewarding behavior of participating in “echo-chambers” accentuate these tendencies.

- Complex systems concepts provide theoretical frameworks and insights important to designing tailored counter violent extremist organizations (VEO) intervention strategies.

- Neurobiological underpinnings, processes of socialization, and the constantly changing modern information environment help illuminate the causes for the bottom up emergence of VEOs. In so doing, they help suggest operational approaches to defeat them.

- Socialization has always required communication. The rapid expansion in digital media dramatically increases the ways that social groups can form, organize, and plan for action.

- Connectedness in the modern information environment tends to reinforce, not replace, basic human needs to connect with others in person.

- Real complex systems do not resemble static structures to be collapsed; they are usually much closer to flexible, constantly respun spider webs.

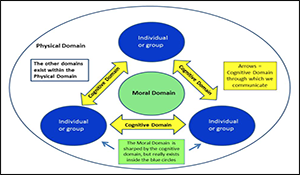

- Countering strategies should focus on the interaction of the physical, mental, and moral domains instead of physically focused, relatively static center of gravity concepts.

- Without an understanding of how all three domains relate to one another dynamically, one may miss the right points of leverage and combinations of interventions that will produce the greatest synergetic effect to influence the direction and momentum of constantly evolving social systems.

- Bottom line: A strategy based on a solid understanding of the dynamic linkages between all three social domains (physical, cognitive, and moral), coupled with solid comprehension of complexity concepts like bottom up emergence, is more likely to help us choose the right combinations of interventions to successfully derail radicalization before violent ideas become violent acts and before violence becomes part of the unquestionable core identity of the individual and the group.

- Emerging research in cyberpsychology and cyberneurobiology can be integrated with existing PSYOP/MISO processes to create both a set of individualized influence tactics and guide their implementation.

- Synthesizing traditional methods with recent advances in neuroscience, cyberpsychology, and captology (the study of persuasive technology) can produce an advanced set of personalized persuasion tactics. This would allow PSYOP/MISO planners to rely on firmly established linkages between perception and actions when developing both their intelligence requirements and the desired psychological effects.

- Research in cyberpsychology and cyberneurobiology should produce empirically informed processes designed to target underlying neural mechanisms to create specific psychological effects on a target.

- Countering VEOs must address target audiences at the macro (population) and micro (individual) levels.

- Bottom line: Appending existing processes to include experimental findings in cyberpsychology and cyberneurobiology along with technological advances from captology will allow the U.S. to combat radicalization across domains with greater precision. Currently, however, there is insufficient empirical data to support explicit linkages between triggers and specific behaviors, and thus experimental validation is necessary.

Selected Chapters:

- Cyber on the Brain: The Effects of Cyberneurobiology & Cyberpsychology on Political Extremism (A. Desjardins)

Contributing Authors

Maj Gen John Shanahan (Joint Staff), Col Marty Reynolds (JS/J-3/DDGO), Lt Col David Lyle (USAF), Ms. Abigail Desjardins (NSI), Maj Dave Blair (Georgetown University), Maj Jason Spitaletta (USMCR), Dr. Panayotis A. Yannakogeorgos (Air Force Research Institute), Dr. Hriar Cabayan (OSD

Topics in the Neurobiology of Aggression: Implications to Deterrence.

Author | Editor: DiEuliis, D. (HHS) & Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff).

This paper provides a series of selected topics on the neurobiological basis of aggression, in the interest of introducing this field of science to the community of experts in deterrence. Thus the topics covered are those of most relevance to inform a deterrence community of how neurobiological considerations may be incorporated as potentially useful tools in deterrence practice. The material is presented in 3 Parts: A summary of the basic neurobiology, a few chapters on behavioral impacts of that neurobiology, and finally a “systems summary” that integrates these issues for readers. Topics include the role of genes and environment, group vs. individual aggressive behaviors, the role of trust and altruism, reward/punishment, and premeditated vs. impulsive aggression, among others. The paper also discusses the continuum of scientific evidence base, from the basic neurobiology of reactive aggression, to pre- meditated aggression and what connections can be understood and conjoined to the psychological and behavioral evidence base.

Key insights provided by contributing authors to this white volume that are of particular relevance to the operational community include:

- It is not possible to understand the biology of behavior without understanding the context in which that biology occurs, as well as the society in which that individual dwells. This is true in our understanding of aggression; there is no highly accurate means of identifying individuals likely to commit an impulsive or planned violent act. The context in which aggression and violence occur can be modified much more easily than identifying individuals likely to commit aggressive act; by manipulating context, society may reduce aggression by individuals indirectly.

- Much aggression is motivated by conflict between in-groups and out-groups. An understanding of genetic and environmental factors can elucidate pathways toward aggression and begin to explain how various environmental factors such as media, propaganda, or informal mechanisms of narrative messaging, can be used to manipulate the neurobiological mechanisms that inform the psychological architecture of susceptible individuals. In that context, foreign policies which overtly impose governance or values alien to local cultures, may constitute provocations to violence.

- Within groups, punishment and reward cannot be understood outside the context of cooperation. Cooperation is stable when defectors can be identified, excluded and/or punished, and when prospective cooperators can be identified, engaged, and rewarded through cooperative exchange. Research indicates reward may function less effectively as a behavior-changing strategy, but may function more effectively as a behavior- sustaining strategy.

- Punishment in the context of group conflict cannot be understood absent the evolutionary logic of warfare between groups in an ancestral environment that was “offense dominant”. The “secure retaliatory force” that nuclear strategists argue is necessary for equilibrium in the nuclear age is nothing but a euphemism for “guaranteed vengeance,” in which states promise a punishment that is greater than the benefits of striking first.

- States where the rule of law is weak can beget societies characterized by “culture of honor” traditions, in which, in the absence of capable and legitimate third-party enforcement, reputation for disproportionate retaliation/punishment becomes the most effective safeguard against personal violence.

- Deterrence as a concept may be a long-learned part of our psychology. Because challenges, predators, or out-group threat have faced humans for millennia, analyzing the notion of deterrence from the perspective of evolutionary models may prove helpful. Rational actors have an interest in settling things with threats but without the use of violence. Vengeance is certain to be provoked by an attack, deterrence kicks in when the initiators cannot be absolutely sure that they’ll be successful.

- Neuroscientific studies of human behavior suggest aggression is a useful but costly strategy and people have a tendency to cooperate in many situations. This has been shown to be chemically regulated, and cooperative behaviors are just as “natural” as aggressive ones. The “Golden Rule” exists in every culture and reveals our essential social nature; this is naturally threatened in situations of threat or high stress.

- Neuroscience and technology offer a viable and potential value of in programs of national security, intelligence and defense. However this will necessitate an acknowledgement of the actual capabilities and limitations of the neuroS/T used – and importantly the ethico-legal issues generated by apt or inapt use, or blatant abuse.

- Context is critically important to our understanding of human behavior and biology is only part of what makes up our human selves and defines us as persons. An integrated approach, one that takes into account the influence of the empirical sciences as well as a social psychological framework, gives us the most holistic understanding of human behavior and produce the greatest improvement in our understanding of terrorism.

Topic Overview

In his introduction, Robert Sapolsky defines “aggression” in the fullest sense as harming, attempts to harming, and thoughts about harming. Two brain regions dominate this. The first is the amygdala, an ancient structure in the “limbic system” (the “emotional” part of the brain). The second is the frontal cortex (FC). It is more complex in humans than in other species, is the most recently evolved part of our brain, and is the last to fully mature (remarkably, in the mid- 20s). There are tremendous individual differences in FC function among people; many of differences arise from differing early life experiences. The limbic system/FC contrast can, in a thoroughly simplistic way, be thought of as a contrast between emotion and thought. A key issue is that genes have far less to do with aggression than is often assumed; genes are not about inevitability, rather, they are about proclivities. In conclusion, Professor Sapolsky states that amid this emphasis on biology, ultimately, it is not possible to understand the biology of behavior without understanding the circumstances of the individual in which that biology occurs, as well as the society in which that individual dwells.