SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

6th Annual SMA Conference: A World in Transformation, Challenges and Opportunities.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & St. Claire, C. (NSI, Inc).

The 6th Annual Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Conference was held at Joint Base Andrews from 6-8 November 2012. The theme of the conference was A World in Transformation: Challenges and Opportunities. A significant portion of the conference addressed the needs of the Geographical Commands. Days One and Two were unclassified, while Day Three was held at the SECRET level.1 As in previous years, representatives from the Geographical Commands were present throughout the conference. On Day Two and on Day Three, representatives discussed the Geographical Commands’ pressing needs to provide the SMA community with an opportunity to mine its wide network of experts to assist in identifying capabilities that can match the Commands’ needs. What resulted was a lively discussion, which is captured in this document.

The Joint Staff, in partnership with OSD, have developed a proven methodology merging multi-agency expertise and information to address complex operational requirements that call for multi-disciplinary approaches utilizing skill sets not normally present within any one service/agency. The SMA process uses robust multi-agency collaboration leveraging intellectual/analytical rigor to examine factual/empirical evidence with the focus on synthesizing existing knowledge. The end product consists of actionable strategies and recommendations, which can then be used by planners to support COA Development. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff and executed OSD/ASD (R&E)/RSD/RRTO.

Findings from Panel Discussions

Guest speaker Mr. Earl Wyatt, Rapid Fielding Office, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering spoke about the Rapid Fielding Directorate’s (RFD) mission to identify, develop, demonstrate, assess, and rapidly field innovative concepts and technologies that supply critical capabilities to meet time-sensitive operational needs. The RFD strives to create a leaner, more agile force to increase effectiveness and maintain U.S. global leadership, which is capable of operating across domains. The RFD strives to deliver technical capabilities to U.S. forces and the speed of delivery needs to accelerate to win current and future fights.

Guest speaker Mr. Ben Riley, Rapid Fielding Office, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, spoke about the relationship between RFD and SMA. Both offices are multidisciplinary, but the RFD is strictly anticipatory in terms of threats. Mr. Riley suggested future SMA projects consider identifying and examining emerging threats, enhancing human capabilities, and developing measures of effectiveness for social science.

Guest speaker Major General John Shanahan, Joint Staff, presented the work that SMA completed in 2012. The South Asia stability project is of increasing importance given the drawdown of forces in Afghanistan, continued ethnic rivalries, and proliferation of tactical nuclear weapons in the region. The cyber neurobiology project examined what effects cyberspace has on radicalization and mobilization and compared that to radicalization and mobilization in the physical realm. Maj Gen Shanahan noted that in order for these projects to add value to the warfighter, they must be operationalized.

Keynote speaker, LTG Michael Flynn, Director, DIA, spoke about the need to reorganize the DIA to meet current and future analytic requirements. He suggested reshaping analytic tradecraft as well as changing the culture of the agency to be more responsive to 21st Century requirements. These changes, dubbed Vision 2020, will include further integration of DIA into the operational community as well as organization changes to flatten hierarchies and increase effectiveness. These analytic and cultural changes are under way in order to more effectively and efficiently support the warfighter.

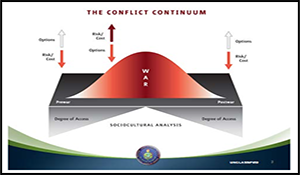

Panel One discussed the future nature of conflict. The panel found that while interstate war will not be obsolete in the future, as some have argued, conflict is likely to occur in nontraditional forms. Particularly worrisome is the diffusion of precision-strike weapons and cyber warfare capabilities by state and violent non-state actors (VNSA). Such capabilities are providing a wider set of actors the ability project force and create disruption at greater distances. Additionally, the future battle space might best be described by three terms: competent, concealed, and congested. The adversary will be competent, the weapons and targets will be concealed, and the terrain will be urban, congested areas.

Panel Two addressed how best to implement effective socio-cultural capabilities to meet the requirements of commanders, staffs, and policymakers at all levels of the Department of Defense (DOD). Social science contributions are often misunderstood by decision-makers. Social science is not a coherent set of disciplines. In fact, “science” implies laws and tested theories, which social science currently lacks. Social science models are not meant to predict, they are meant to inform. They provide the DOD with better questions, not better answers. If the DOD did not have social science, it would be much further behind in facing complex problems. However, further clarity of thought and method is necessary to help the DOD address complex challenges.

Invited speaker Dr. Robie Samanta Roy, Senate Armed Services Committee, spoke about the role of social science in war planning and the operational community. However, there are four key issues that must be addressed to ensure the effectiveness of this relationship, listed below.

- The gap between the research and user community must be bridged.

- Increase coordination within the research community is required.

- There is a need to ask the right questions to address pressing problems and accurately measure the effectiveness of social science solutions.

- Maintaining and encouraging the multidisciplinary nature of social science research

Shaping social science research in the DOD must happen now to prepare for the challenges of tomorrow.

Panel three explored the question, What can remote data collection of the Earth’s environmental factors and population dynamics reduce the collection demands for assessing local, state, and regional stability? The panel found that remote data collection could be fused with social science models to inform trends and outcomes as long as the data used is good. Remote data collection has increasingly practical applications, including the development of the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) that helps planners decide to intervene in a food crisis or not.

Panel Four addressed how defense social science basic research, and the MINERVA Research Initiative in particular, can address mission-relevant questions such as the motivation for violent extremism or the indicators of social conflict and stability. Basic research builds cultural and foreign area knowledge and creates insights to inform more effective strategic and operational policy decisions by war planners and warfighters. It leverages and focuses the resources of the nation’s top universities toward fields of critical DOD interest. Finally, it fosters a community of subject matter experts in regions and social science topics of known interest—and what may be of future interest.

The Feedback from Command Panel asked representatives from the COCOMs, “What are the pressing needs in your commands?” Each COCOM is concerned with maintaining effectiveness in the increasingly resource constrained environment. Critical to this effectiveness is increasing collaboration with regional partners and other agencies and the development and utilization of Special operations forces (SOF).

Panel Five focused on how organizations outside the DOD confront complex problems in the information environment. The panel emphasized that while the USG has made great strides in adapting and employing new technologies, like social media, it must take further steps to collaborate and coordinate efforts across the whole of government. This will require a culture of collaboration—it cannot be a boutique effort within various agencies. The USG must continue to adapt and do business differently in the 21st Century.

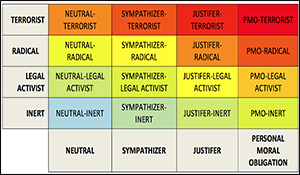

LtGen Robert Schmidle, Deputy Commandant for Aviation, USMC, presented a talk on the psychological and social theories in radicalization and terrorist networks. Social theories make three major contributions to defense analysis: they 1) ground decision makers in context, 2) help analysts understand why individuals radicalize, and 3) combine with technology and physical sciences to increase understanding of complex issues.

Panel 6, Insights from Neurobiology on Influence and Extremism, focused on presenting multi-disciplinary cutting-edge research insights for the operational community. Use of neuroscience and neurotechnologies can help create a full picture of the brain and its activities. Of particular interest to the planning community is the role of aggression in terrorist activities. Further research on the interaction of brain structure, function, genetics, and social, individual, economic, and environmental factors is needed to fully inform aggression. U.S. warfighters must consider neurobiology in operations planning and execution.

Panel Seven discussed how new insights from both neuroscience and network sciences are likely to change the way the military conducts operations, to include influence operations, intelligence analysis, psychological and military information support operations, and cyber activities. Cyber space is becoming increasingly complex and is expanding at an incredible rate. Information technology has become so pervasive that some suggest the first indicators of conflict would come from cyber/social media. Another way the information environment is changing Information Operations (IO) is that it is now a two-way street; and operators need to be prepared to respond to messages in near real time. The issue of online attribution is important. In the physical realm, one must declare one’s allegiance. In the online realm, one’s identity is fungible. Science has advanced to the point where it can help inform when to disclose online identity and when not to. However, this area deserved a tremendous amount of further study.

Panel Eight members agreed on the need to dive deep into the operational environment to anticipate future threats and increase the agility of U.S. forces. However, changes in the Intelligence Community (IC), culture shifts in existing institutions, and development of intelligence fusion centers are necessary for effective planning and implantation of this analysis. Understanding how economic, social, and political issues will coalesce over time will allow for better planning and even anticipation of events. It is necessary that futures analysis makes connections across disciplines in order to arrive at conclusions that are valuable for futures planning.

South Asia Stability Assessment Academic Consortium.

Author | Editor: Popp, G., Canna, S. & St. Claire, C. (NSI, Inc).

This report supported SMA’s Geopolitical Stability in South Asia project. For additional information, please visit the South Asia project page.

The Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) office provides planning support to the Combatant Commands with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi- disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. Solutions and participants are sought across the United States Government (USG) and beyond. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff and executed by ASD (R&E)/RFD/RRTO.

The Minerva Research Initiative is a university-based research program which aims to provide deeper understanding of the social and cultural forces that shape regions of the world of strategic importance to the U.S. Started by former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates to foster stronger connections between the Department of Defense and the academic social science community, its core is fundamental research, driven by some of the Nation’s leading political and social scientists, to understand sources of present and future conflict. An increasingly important secondary role of the Minerva program is more short term: not to focus funded basic research on solving applied problems, but to connect decision makers to talented pools of academics whose research has given them relevant subject matter expertise.

Over the last several months, the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) and Minerva Research Initiative worked to convene an Academic Consortium to complement the South Asia Stability project. The objective of the project is to develop options for promoting geopolitical stability in South Asia in light of continuing regional rivalries, the eventual withdrawal of International Security Assistance Forces (ISAF) from Afghanistan, and the preponderance of violent extremist organizations (VEOs) in the region. Deterrence of multiple, possible crisis scenarios is a central aspect of the effort. Members of the Consortium contribute knowledge and expertise either via short papers on topics of concern to the operational community or via webinars in support of the SMA office. The analyses of the effects of potential U.S. actions and associated risk assessments produced by this effort are intended to assist and inform USCENTCOM, USPACOM, USSTRATCOM, and JS planners/operators and others interested in stability and instability factors in South Asia.

The Consortium presentations reported in this document were geared toward the Approaches to Countering Instability component of the larger South Asia effort that explored the internal and external sources of stability and instability as well as options for mitigating negative trends. In addition to their value as stand-along pieces, consortium insights were used as inputs to a number of the South Asia Stability project’s sub-tasks including a Stability Risk Assessment event conducted by Pacific Northwest National Lab (PNNL) with input from Lawrence Livermore National Lab (LLNL), as well as the Pakistan Stability Model (PAK-StaM) analyses of the main economic, social, and political drivers of stability and instability in Pakistan.

Executive Summary

The Academic Consortium webinars were held in August 2012 on behalf of the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) South Asia Stability project. The effort seeks to elicit knowledge about topics of interest to the operational community in support of the SMA South Asia Stability project. Academic Consortium presenters include Dr. Joseph Nye, Dr. Sumit Ganguly, Dr. Kanishkan Sathasivam, Dr. Martha Crenshaw, and Dr. Jocelyne Cesari.

Joseph Nye

Dr. Joseph Nye is University Distinguished Service Professor at Harvard University and former Dean of the Kennedy School and is a member of the Aspen Institute’s U.S.-India Strategic Dialogue1 group. He spoke to members of the SMA team via teleconference on 15 October 2012.

Dr. Nye’s discussion focused on strategic stability in South Asia given regional economic decline, the drawdown of ISAF forces in Afghanistan, shifting demographics in Pakistan, and the growing size and decentralization of the Pakistan nuclear stockpile. His points are briefly summarized below.

- ?The main concern in South Asia is no longer Pakistan’s relationship with India or any other external actor, but the future of the Pakistani state and society itself. Not only has Pakistan’s government and economy declined over recent years, the population is moving from a relatively pluralistic, Sufi-oriented society with a strong secular element to a more extreme, Salafi-oriented society.

- ?These changes give rise to new concerns about Pakistan’s ability to maintain control of its growing, increasingly decentralized nuclear weapons program.

- ?The drawdown of ISAF forces in Afghanistan will have some effect on the strategic balance in South Asia, but it is not clear whether Pakistan, India, China, or even Iran will attempt to fill in the power vacuum.

- ?Slow economic growth in India is troublesome for regional stability. The question of how to get economic growth in India back to 8-9 percent and keep it there is critical to India’s, and the region’s, stability.

Sumit Ganguly

Dr. Sumit Ganguly, Indiana University, presented a talk on the prospects of stability in South Asia on 9 August 2012 as part of the SMA South Asia Stability project’s Academic Consortium.

Dr. Ganguly’s presentation on the prospects of stability in South Asia focused on systemic, national, and decision-making factors and their likely impact on regional stability in South Asia. Among other matters, Dr. Ganguly discussed the impending U.S. drawdown of forces in Afghanistan; the growth and possible assertion of Chinese military power; political developments within India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka; and leadership challenges in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. Dr. Ganguly concluded with a discussion of the implications of these developments for U.S. policy toward the region. Key findings from Dr. Ganguly’s presentation are listed below.

- The implications of the United States drawdown in Afghanistan and a greater assertiveness of the People’s Republic of China in the Indian Ocean will be the two most important systemic factors impinging on regional security in South Asia in the foreseeable future.

- There are a number of national-level factors throughout South Asia that will have an important impact on regional stability. These national factors include the future of the Tamil minority in Sri Lanka, the future of Indo-Pakistani relations, Pakistan’s pursuit of tactical nuclear weapons, India’s quest for ballistic missile defense, the plight of the Rohingya minority in Burma (Myanmar), the resurgence of Hindu- Muslim discord in India, and the resurrection of the Maoist movement throughout India.

- There are four potential leadership factors in South Asia that could have important consequences for stability in the region. These leadership factors include the looming transition of leadership in Bangladesh, the major challenges for Pakistani President Zardari in Pakistan, the shaky status of Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai in Nepal, and the uncertain prospects of the coalition regime in India.

- To assist in preventing instability in South Asia, United States policy must take serious consideration into how the U.S. carries out its withdrawal from Afghanistan and must also ensure that the government of India does not neglect the critical policy choices of its future.

Kanishkan Sathasivam

Dr. Kanishkan Sathasivam, Salem State University, presented a talk entitled, “Does Pakistan Have a Foreign Policy?” on 13 August 2012 as part of the SMA South Asia Stability project’s Academic Consortium.

Dr. Sathasivam’s presentation argued that in the post-9/11 regional strategic context, Pakistan does not have an identifiable, coherent foreign policy or foreign policy-making framework. Pakistan’s current foreign policy essentially consists of a series of ad hoc policy decisions that have been reactive to regional strategic conditions and events. Furthermore, given its inability to generate a contemporary foreign policy-making framework, Pakistan has fallen back on its perceived historic grievances as the fundamental basis for these ad hoc foreign policy decisions.

Martha Crenshaw

Dr. Martha Crenshaw, Stanford University, presented an effort to map al Qaeda affiliates and analyze implications of these groups for stability in Pakistan on 17 August 2012 as part of the SMA South Asia Stability project’s Academic Consortium.

Dr. Crenshaw’s presentation introduced and explained the maps of terrorist organizations that have been developed as a reference tool for researchers. The purpose of the mapping project is to identify patterns in the evolution of terrorist organizations, specify their causes and consequences, and analyze the development of al Qaeda and its cohort in a comprehensive comparative framework. These maps identified patterns in the evolution of militant organizations since the 1970s and provide interactive visual representations of the groups over time. Countries that are or will be mapped are Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Algeria/Maghreb, Pakistan, Colombia, the Philippines, the Palestinian resistance movement, Italy and Germany in the 1970s and 1980s, and Northern Ireland. The maps that have been completed thus far by Dr. Crenshaw and her team include Iraq, Somalia, Pakistani Al Qaeda affiliates, and Italy. Dr. Crenshaw spoke about the Pakistan map and its implication for regional stability. Key findings and insights from this presentation are listed below.

- Pakistan is one of the most complicated, dense, and volatile landscapes of militant organizations

- Some of the complexity is due to the interaction of sectarian, jihadist, nationalist, and separatist militant groups

- State sponsorship creates rivalries between these groups

- Recently, controlling these groups has become harder now that they have established themselves as independent from their state sponsors

Jocelyne Cesari

Dr. Jocelyne Cesari, Harvard University, presented a brief on state and society relations and their influence on the political stability of Pakistan on 20 August 2012 as part of the SMA South Asia Stability project’s Academic Consortium.

Jocelyne Cesari’s Minerva research addressed an unexamined dimension in the politicization of Islam, that is, state actions and policies vis-à-vis religion in general and Islam in particular. Politicization in this context is broader than Islamism and encompasses the following.

- Nationalization of Islamic institutions and personnel

- Usage of Islamic references in political competition by state actors and opponents (Islamism)

- Religiously-motivated social unrest or violence

- Internationalization of Islam-orientated political movements or conflicts

The research adopted an institutional approach to Islam in order to introduce state actions and policies into the analysis of political influence of cultural and religious changes at both the domestic and international levels. Institutionalization refers to the way new socio- political situations are translated into the creation or adaptation of formal institutions such as constitutions, laws, and administrative bodies and agencies. This translation is salient over two matters: hegemonic status granted to on religion and state’s regulations of religions. Hegemonic status refers to legal and political privileges provided to one religion over the others, usually the dominant religion.

Dr. Cesari’s research showed that legal privileges characterize the majority of Muslim countries, where legal and political rights have generally been granted to the dominant orientation of Islam and highlights the correlation between institutionalization of Islam and politicization of religion. The political consequence is that religious norms become the substratum of social norms and political cultures in most of Muslim majority countries, as illustrated in the evolution of Pakistan from a State for Muslims to an Islamic State. In particular, Dr. Cesari’s research shows that the hegemonic status of religion increases social and political violence across regions and religions. Such a political and social violence can affect regional stability. Due to the hegemonic nature of Sunni Islam, and the increasing Islamicization of the legal system, religious minorities and women are becoming increasingly vulnerable. Freedom of speech is more and more restricted to conform to a more “Islamically correct” public space. When in public spaces, citizens are cautious of what they say and how they act, in large part due to possible consequences from some religious actors that are rarely sanctioned by the Government. It is unclear how these restrictions will affect domestic and regional stability but it does create ground for political actors acting on religious ground.

Dr. Cesari noted that urbanization and the role of media must also be considered when analyzing the current situation in Pakistan. Recently, more Pakistanis are moving to cities which will ultimately weaken tribal legitimacy which has played an important role in the stability of the political system until now. New political players are emerging on the political scene, which may in turn threaten the traditional political and military elite. Additionally, media out of State control could be used as alternative forums to express opinions and discontent, further destabilizing the current system.

Contributing Authors

Dr. Joseph Nye, Dr. Sumit Ganguly, Dr. Kanishkan Sathasivam, Dr. Martha Crenshaw, Dr. Jocelyn Cesari

Pak-StaM Analysis Drivers of Stability & Instability in Pakistan.

Author: Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois, et al. (NSI, Inc).

This report supported SMA’s Geopolitical Stability in South Asia project. For additional information, please visit the South Asia project page.

This report addresses a number of key questions regarding the factors that underpin stability and instability in Pakistan. In particular: Which are the factors that most significantly contribute to governing, economic, and social stability in Pakistan? Are there factors commonly associated with stability that have no effect or have divergent effects on stability in Pakistan? What are the primary effect dependencies among factors? Is the effect of specific factors likely to change with time?

Pakistan sits at the center of South Asian regional security dynamics. Each of its several international borders has been both the cause of inter-state dispute and the site of militarized conflict. There are high levels of crime, violence, and sectarian conflict, and the writ of the state is challenged in many areas of the country. Porous borders facilitate organized crime, and militant activity further challenges state control and threatens the physical security and wellbeing of the Pakistani people. Investment (both government and private) in the weakly institutionalized, corrupt, and aid-dependent formal economy is insufficient to keep up with population growth, let alone enable Pakistan to reach its Millennium Development Goals. Finally, weak civilian governance, and a strongly politicized military blurs the lines of de jure authority.

Yet, despite these significant problems and frequent predictions of imminent failure of the Pakistani state, Pakistan persists. Struggles over division of authority between the judiciary and elected leaders have weakened but not toppled the civilian government, or triggered a military coup. While militants continue to challenge the writ of the state, they have not succeeded in fracturing Pakistan or establishing uncontested control. Discussion of the causes of Pakistan’s problems, and prescriptions for their cure are plentiful; however, there is less to be found on the factors that have enabled the Pakistani state and people to survive these challenges. Addressing the question of why Pakistan has not failed is equally important if we are to develop a complete picture of Pakistan’s current situation and future trajectory. This requires us to determine not only the factors that drive instability, but also those that buffer stability.

The following report addresses a number of key questions regarding the factors that underpin stability and instability in Pakistan. In particular:

- Which are the factors that most significantly contribute to governing, economic, and social stability in Pakistan?

- Are there factors commonly associated with stability that have no effect or have divergent effects on stability in Pakistan?

- What are the primary effect dependencies among factors?

- Is the effect of specific factors likely to change with time?

The analysis uses a conceptual model of state stability—the StaM—to systematically identify the drivers of instability as well as the areas of resilience in Pakistan. We find that while there are evident drivers of instability, there are also less immediately evident areas of resilience that buffer the stability of the state of Pakistan and its people. Moreover, the factors that appear to underpin Pakistan’s resilience to collapse are closely linked to those that may promote instability in the longer term. That is, it appears that, for Pakistan, shorter-term stabilizers can easily become destabilizers in the longer term. Conversely, there are factors that disrupt to the status quo, and can appear destabilizing, but are in fact an essential part of generating the structural changes Pakistan needs to achieve long-term stability. Accounting for both the short-term and long-term effects of various drivers of stability is essential for understanding their full implications for stability.

The remainder of this chapter provides a brief introduction to the StaM and our analysis of Pakistan. Development and analysis of the model specified to Pakistan–the Pak-StaM–illuminated several factors that appear to be pivotal to stability conditions in Pakistan. Each subsequent chapter explores the short and longer-term implications of a critical domestic factor identified as driving stability conditions in Pakistan including:

- the grey economy;

- formal foreign remittances;

- patronage;

- weak civilian institutions;

- education; and

- access to information.

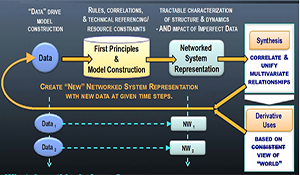

The Stability Model (StaM)

A well-founded conceptual framework is an essential tool for any systematic analysis, especially when dealing with a concept as complex and interdependent as state stability. Whether acknowledged or not, all analyses are conducted in reference to some theory or implicit mental model. A conceptual model is simply a formal articulation of this same process. By specifying the factors that contribute to a phenomenon and the relationships between them, conceptual models help the analyst to check the logic, consistency, and comprehensiveness of the explanation and to understand not only what might occur but why, and what might be done to either encourage or impede it.

For the purposes of the analyses described in the following chapters, the overall durability (versus fracture) of a nation-state is defined as a compound function of its political, economic, and social stability. Each of these is performance-based where the political system is able to

- maintain a degree of legitimacy, political performance, and/or the coercive power necessary to retain internal control;

- sustain sufficient growth in the economic system (formal or informal) to support the minimal needs of the majority of citizens (i.e., the average growth rate in productivity exceeds the growth rate in population); and

- ensure that social cleavages do not result in violent ethnic or sectarian conflict.

The analysis of stability and instability drivers in Pakistan presented here employs the Stability Model (StaM) as an organizing framework for assessing political stability over the mid- to longer-term. According to the generic StaM,3 overall state stability arises from three necessary, but not sufficient, dimensions: economic stability, social stability, and governing stability. The definitions of these dimensions and their disaggregation are based on a wide range of academic and applied research and theory (including anthropology, international relations, comparative politics, social psychology, and economics).

Before using the StaM to assess stability dynamics in a specific context, further specification and tailoring of the model to that state or region is required. To begin the search for key drivers of stability and instability in Pakistan, analysts used the generic model as a set of assertions or hypotheses about political, economic, and social dynamics to guide their search for Pakistan-specific data. In an iterative process, researchers used the model’s organizing structure and the predicted relations within and across dimensions (governing, economic, and social stability) to gain insight into complex stability dynamics that characterize Pakistan. In all, over 1000 unclassified sources were used to tailor the generic StaM for Pakistan. These included: quantitative data on political processes, popular perceptions and opinion, and economic and financial flows; extensive area expert elicitation; current research on social, ethnic, economic and political and institutional cultures in Pakistan; social geography; and assessment of authority and political transitions through Pakistani history.

As information was gathered, three types of alterations were made to the generic model. This tailoring process, beginning with the generic model in Figure i-1, generated the specified Pakistan model shown in Figure i-2. The first step involved adjusting, adding, or eliminating factors shown in the generic StaM to align with the Pakistan context. For example, to account for its strong political influence, the Pakistani military was added to the generic model as a political actor with its own source of legitimacy in competition with civilian governors and interests. In the generic model, the role and performance of the military is incorporated under rule of law and national security. It was also necessary to distinguish explicitly between internally and externally generated revenue, as Pakistan is heavily dependent on foreign aid and loans to provide public services. The second type of alteration involved further disaggregating the generic factors to capture their state-specific nature (e.g., the components that constitute quality of life from the perspective of Pakistani culture, rather than U.S. culture). Finally, researchers considered whether the between-factors relationships anticipated by the generic model existed in the same way, or indeed at all, in the Pakistan context and confirmed or redrew these connections accordingly.

Once the model was tailored, and concepts defined for the Pakistan context, analysts set about the more complex task of assessing the extent to which each if these drove instability or provided a buffer to stability. This process led to the identification of the six major determinants of stability that form the structure of this report: the grey economy, formal foreign remittances, patronage, weak civilian institutions, education, and access to information. “Following the thread” of each of these factors through the model allowed us to build a picture of how these dominant factors affected stability within and across dimensions and over time. Using the model to follow stability implications in this way provides a number of benefits to the analyst and planner.

- Cross dimensional analysis accounts for the interactive complexity of state stability and provides better insight into the dynamics driving the complex macro system that is Pakistani state and society.

- By distinguishing between short and longer-term effects, the Pak-StaM can help analysts identify situations (e.g., patronage) that may buffer stability in the short-term, but ultimately block many of the structural changes required for longer-term stability.

- The ability to account for domestic stability effects of regional actors enables detailed mapping of the regional influences on Pakistan’s stability. Where specifically do the interests of regional actors affect stability in Pakistan? In addition, is it possible to map the effects of external actors’ interests on Pakistan’s domestic dynamics?6

- The StaM suggests a new perspective on how we think about stability and change in countries such as Pakistan. In particular, the United States Government (USG) needs to recognize that not all short-term instability is bad. In fact, short-term disruption is the likely result of the very structural changes–social, political and economic—Pakistan needs in order to achieve longer- term stability and development.

Caveats

The StaM is not a computational model; it presents a conceptual map intended to help trace and describe complex and multi-dimensional relationships. Even the generic StaM is highly complex and incorporates multiple theories from diverse disciplines. Although theory is sufficiently well developed and tested to create computational models of discrete sections of the StaM, compiling these into a single computational model of the entire StaM would require the imposition of a great number of assumptions regarding the relative weighting and interactions between the components. We currently lack the theoretical and empirical knowledge to model with any level of confidence. For similar reasons, there is no precisely delineated scale of time in the model.

Our “short term” and “long term” are better understood as “current” and “sometime in the future, all else being equal and given current patterns.” Neither the StaM nor the data available are sufficient to make definitive, point-predictive assessments of where things are going in Pakistan (e.g., as a time- series regression analysis on economic data or sales figures) other than to say, “if things stay the same, x is the most likely outcome” or “if y changes, z is the most likely outcome.” Nearly all of the effects in the Pak-StaM are interconnected and highly conditional. To predict what might happen on the basis of what we see now would require more assumptions, including the absence of any significant changes in factors in the period under study, than it is reasonable to make.

Contributing Authors

Belinda Bragg, Danette Brickman, Sarah Canna, George Popp, Alex Stephenson, Richard Williams (NSI)

National Security Challenges: Insights from Social, Neurobiological, and Complexity Sciences.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc), Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff), Casebeer, W. (DARPA), Desjardins, A. (NSI, Inc), DiEuliis, D. (HHS), Ehlschlaeger, C. (ERDC), Lyle, D. (USAF) & Rice, C. (USA/TRADOC).

This White Volume assesses U.S. long term national security challenges, employing a global perspective that accounts for the changing political, economic, social, and psychological profiles of populations, and the rapid changes they experience in a globally connected information en- vironment. It addresses many of the key national security challenges iden- tified by LTG Flynn in the Preface. The collection of essays explores future population-centric national security challenges through the lens of the lat- est research from the social, neurological, and complexity sciences. The papers emphasize “enduring” long term themes that are focused on the in- teractions of populations and their environments. They are not U.S.- centric, but multi-perspective and examine underlying long term phenom- ena.

The target audiences are planners, operators, and policy makers. With them in mind, the articles are intentionally kept short and written to stand alone. All the contributors have done their best to make their articles easi- ly accessible.

This white paper addresses many of the key national security challenges identified by LTG Flynn in the Preface, including the following:

- The threat environment is highly asymmetric, amorphous, complex, rapidly changing and uncertain.

- There is need for speed and flexibility in U.S. intelligence gathering and decision making.

- Current analytic deficiencies arise from the Cold War structure and in- sularity of the IC, complexity of the environment, and how we currently think about threats.

- New thinking needs to consider populations as important actors (e.g., mobilization via social media, etc.) and the social and resource inequi- ties and grievances that spawn conflict.

- Following the end of the Cold War, the expected “peace dividend” has failed to materialize; the U.S. has experienced an era of persistent conflict

General Flynn’s remarks suggest a number of specific challenges to ana- lysts and planners:

- Reevaluate our concept of what constitutes a “threat” in the current and evolving world environment both from a U.S. and foreign perspec- tive.

- Expand the sources of information used to understand the environ- ment.

- Consider the population of an area as an important actor; also, assess outside entities within the periphery of destabilization that have the ability to leverage support to insurgent groups, which will negatively effect U.S. operations.

- Be proactive; focus on the causes and precursors of conflict rather than solely war and conflict.

- Learn to understand and respond flexibly and faster; be more “adap- tive” and forward thinking.

The overriding theme in this White Volume is how best to assess U.S. long term national security challenges, employing a global perspective that ac- counts for the changing political, economic, social, and psychological pro- files of populations, and the rapid changes they experience in a globally connected information environment.

The target audiences for this White Volume are planners, operators, and policy makers. With them in mind, the articles are intentionally kept short and written to stand alone. All the contributors have done their best to make their articles easily accessible. The papers emphasize “enduring” long term themes that are focused on the interactions of populations and their environments. They are not U.S.-centric, but multi-perspective and examine underlying long term phenomena.

In describing these long term challenges, it is important to remember that we are dealing primarily with human behavior rather than physical phe- nomena. Methods involving mechanistic approaches and point predictions will not be feasible; rather we will describe techniques to map out ranges of possible futures. The difficulties are increased because security threats are global in scale and must be anticipated as far in advance of a crisis as possible. Multidisciplinary approaches are called for and validation of models may be difficult, costly, or in some cases impossible.

This collection of essays explores future population-centric national secu- rity challenges through the lens of the latest research from the social, neu- rological, and complexity sciences. The first section, Populations in their Environments: Factors Impacting the Fragility of “Peace,” argues that an understanding of a population’s propensity for social and political conflict is not possible without an appreciation of how its needs and interests re- late to and are affected by the physical environment. The second section, Global Patterns and Trends in Armed Conflict: Evidence and Theories, describes recent and ongoing research on historical patterns and trends in armed conflict, which have documented a systemic decline in armed vio- lence worldwide since the end of the Cold War, even as the U.S. has expe- rienced an “era of persistent conflict.” The third section, Neurobiological, Cognitive and Social Science Insights on Radicalization and Mobilization to Violence discusses the neurological and cognitive drivers of the social behaviors that propel people to radicalize and pursue violence. The fourth section, Seeing the World As it Is: Complex Adaptive Systems Approaches as Multi-source, Multi-input Integrators discusses the potential of complexity science to help us combine insights from the other disciplines into a coherent system of understanding, and apply this framework directly to the challenges military planners face. The fifth section, written by Admiral James Stavridis and Dr. Evelyn Farkas, speaks to the importance of partnership and collaboration between public and private organizations to achieve mutually desired security outcomes. Finally, Dr. William Casebeer from DARPA provides an epilogue considering insights from the first two sections and how the complexity sciences might be employed to address the challenges faced by strategic thinkers, military analysts and planners, and decision makers.

Contributing Authors

Dr. Janice Adelman (NSI), Mr. Azad Amir-ghessemi (PERTAN Inc), Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI), Dr. Greg Berns (Emory University), Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI), Mr. David A. Browne (PACOM), Dr. Emile Bruneau (MIT), Mr. Jeffery Burkhalter (USA/ERDC), Mr. William Busch (EUCOM), Dr. Hriar Cabayan (OSD), Dr. Bill Casebeer (DARPA), Ms. Abigail Chapman (NSI), Dr. Joan Chiao (Northwestern University), Dr. Claudio Cioffi-Revilla (George Mason University), Dr. Eric Dimperio (USA/ERDC), Dr. Diane DiEuliis (HHS), Ms. Marina Drigo (PERTAN Inc), Mr. Patrick Edwards (USA/ERDC), Dr. Charles R. Ehlschlaeger (USA/ERDC), Dr. Evelyn Farkas (EUCOM), LTG Michael Flynn (DIA), Dr. James Giordano (Potomac Institute for Policy Studies), Dr. Peter Hatemi (Penn State University), Dr. Cullen S. Hendrix (College of William & Mary), Mr. Eric A. Knudson (PACOM), Mr. Joseph T. Lee (PACOM), Mr. Kalev Leetaru (University of Illinois at Urbana), Lt Col David Lyle (USAF), Dr. Rose McDermott (Brown University), Ms. Shana McLean (EUCOM), LTC (Dr.) Rob Neff (SOCOM), Dr. Anthony Olcott, COL (Dr.) Christopher Rate (SOCOM), Dr. Christopher Rice (USA/TRADOC), ADM James Stavridis (EUCOM)

Neuroscience Insights on Radicalization and Mobilization to Violence: A Review, Second Edition.

Author | Editor: Canna, S., St. Clair, C. & Desjardins, A. (NSI, Inc).

Radicalization is a complex phenomenon informed by various disciplines. The social sciences have provided planners and operators with an understanding of the ‘who’, ‘what’, and more recently the ‘how’ of radicalization. The neuroscience community is working to expand the understanding of ‘why.’ It is essential that planners and operators, who are often on the front line of counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency campaigns, have a deeper understanding of the why and how radicalization occurs. With a better understanding of the ‘why’ aspect of radicalization, planners, operators, and social scientists can move beyond purely correlative work. This report offers insights from these various fields in an easily accessible format for the operational and planning communities.

The Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) team—in partnership with federal organizations, industry, think tanks, and academia—has explored the concepts of radicalization and political extremism over the last several years, delving deep into analytic methods, subject matter expertise, and modeling experiments to assist military planners and operators in understanding and more effectively responding to the threat of radicalization. This review, intentionally concise, will summarize findings from previously edited volumes, conference proceedings, journal articles, and white papers produced by or for the SMA community exclusively. It is important to note this is not a comprehensive review of all open source material(s) on the topic, and as such, the reader should be aware the materials presented within were prepared specifically for SMA purposes and may not address all topics or issues within the field of study. This review presents theories, findings, and techniques from neuroscience, as well as insights from the operational community, to provide a current and comprehensive description of why individuals and groups engage in violent political behavior.

We reviewed approximately 3,000 pages of literature prepared for or by the SMA team. The full list of reviewed documents is available in Appendix A, but the core documents are listed below.

- Cyber on the Brain: The Effects of CyberNeurobiology CyberPsychology on Political Extremism (October 2012)

- Influencing Violent Extremist Organizations Pilot Effort: Focus on Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (Fall 2011)

- SMA 5th Annual Conference Proceedings 29-30 November 2011 Panel on Implications of Recent Advances in Social, Cognitive Neurobiological Science to National Security

- Countering Violent Extremism: Scientific Methods Strategies (September 2011)

- Neurobiology of Political Violence: New Tools, New Insights (December 2010)

- Defining a Strategic Campaign for Working with Partners to Counter and Delegitimize Violent Extremism (May 2010)

- Protecting the Homeland from International and Domestic Terrorism Threats: Current Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives on Root Causes, the Role of Ideology, and Programs for Counter-radicalization and Disengagement (January 2010)

- From the Mind to the Feet: Assessing the Perception-to-Intent-to-Action Dynamic (July 2009)

Background

Findings from the neuroscience community may often be challenging for the military analyst, planner, and decision maker to access for various reasons.

- The neuroscience of behavior is a relatively new field, with many phenomena not yet studied.

- Neuroscience research is primarily conducted within a controlled lab setting, and while insights can be generalized, the research findings are often narrow in scope.

- Neuroscience findings are not often directly applied to issues of national security.

- Neuroscience literature may not be easily accessible.

However, neuroscience findings can augment understanding of political violence gained through social science research or personal experience. Related to this, neurocognitive research has been identified as a field of opportunity for national security and national defense (National Research Council of the National Academies, 2008 and 2009). It can be expected that as this field of endeavor expands, much will be of utility to our understanding of the social aspects of violent extremism/radicalism. Some would argue that without an understanding of the biological basis of decision-making and motivation, the social sciences are restricted to correlative work, which is useful, but can only take one so far. Others suggest that neuroscience is on the brink of helping decision makers distinguish between the intended, stated, and actual behaviors of an individual or group’s behaviors. More subtle and effective policies and plans can be crafted using multidisciplinary approaches.

How to Use this Document

This report is a living document that provides concise, encyclopedic-level information about advances in neuroscience that help inform how individuals become radicalized. The report distills thousands of pages of theories and research into one 60-page document. Much of the complexity, nuances, and limitations of the findings were lost in the effort to provide an easy to understand overview of the research. However, the findings and hypotheses cited are well documented and links are provided to the primary literature to allow readers to seek more detailed information.

Insights from Neurobiology on Influence and Extremism.

Author | Editor: Orlina, E. & Desjardins, A. (NSI, Inc).

These reports will provide the operational and policy communities with a deeper understanding of the unique behavioral and neurobiological factors that underlie political extremism, specifically in the cyber realm. There are three volumes contained within this series:

- Cyber on the Brain: Insights from CyberPsychology and CyberNeurobiology on Political Extremism

- Topics in Operational Considerations on Insights from Neurobiology on Influence and Extremism

- The Neurobiology of Aggression/Counter-Aggression

This white paper provides a unique and multi-disciplinary perspective on political extremism in the cyberspace realm by assessing the processes by which political extremism is affected by advances in communication technology and the online environment. Advances in the Internet and related technologies have played, and continue to play, an important role in all aspects of national security. The convergence of technology and social media has presented great opportunities, but also generates security risks. It is suggested that cyber-based communications technology helps foster connections among groups of individuals, allowing for the spread of memes and movements for peaceful change. Yet, at the same time, the Internet and related technologies may enhance the emergence of violent extremist organizations as well as subsequent recruitment. This is an exploratory first step towards understanding the implications for cyber-based communications technology on the root factors pertaining to political extremism.

Advances in the Internet and related technologies have played, and continue to play, an important role in all aspects of national security. The convergence of technology and social media has generated opportunities for improved target audience communications and interventions, but also provides individuals who may seek to harm with the ability to communicate their own messages and ideologies around the world quickly and broadly. These opportunities, and the development and continued advances in cyber technologies including the Internet and social media applications and websites, present the United States Government (USG) and its allies with numerous intervention scenarios though there also are potentially grave risks. While these technologies help foster connections among groups of individuals, allowing for the spread of viral advertising, ideas, and memes1 as well as movements for political change, they may also have facilitated the emergence and extended the reach of violent extremist organizations (VEOs).

The main question guiding this inquiry is: What are the implications of cyber-based communications for theories of political mobilization and mass radicalization? This document seeks to explore cyber- related implications for key concepts underlying current models of radicalization and mobilization (e.g., norm generation and propagation, cultural and genomic adaptations, attitude and belief formation). It explores peer-reviewed academic research on the topic of political extremism, radicalization, and mobilization in light of advances in communication technology and the online environment. In addition, interviews were conducted with researchers to ensure that even yet-to- be-published research findings were included. This report builds directly on recent Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) projects pertaining to political extremism and countering violent extremism including the June 2012 SMA report entitled “Neurobiological & Cognitive Science Insights on Radicalization and Mobilization to Violence: A Review,” while drawing on the vast literatures and ongoing research of scientists in the fields of neurobiology, social and cognitive psychology, social and cognitive neuroscience, political science, anthropology, communication science, and other related disciplines.

The Effects of CyberNeurobiology and CyberPsychology on Political Extremism.

Author | Editor: Orlina, E. & Desjardins, A. (NSI, Inc).

These reports will provide the operational and policy communities with a deeper understanding of the unique behavioral and neurobiological factors that underlie political extremism, specifically in the cyber realm. There are three volumes contained within this series:

- Cyber on the Brain: Insights from CyberPsychology and CyberNeurobiology on Political Extremism

- Topics in Operational Considerations on Insights from Neurobiology on Influence and Extremism

- The Neurobiology of Aggression/Counter-Aggression

This white paper provides a unique and multi-disciplinary perspective on political extremism in the cyberspace realm by assessing the processes by which political extremism is affected by advances in communication technology and the online environment. Advances in the Internet and related technologies have played, and continue to play, an important role in all aspects of national security. The convergence of technology and social media has presented great opportunities, but also generates security risks. It is suggested that cyber-based communications technology helps foster connections among groups of individuals, allowing for the spread of memes and movements for peaceful change. Yet, at the same time, the Internet and related technologies may enhance the emergence of violent extremist organizations as well as subsequent recruitment. This is an exploratory first step towards understanding the implications for cyber-based communications technology on the root factors pertaining to political extremism.

Advances in the Internet and related technologies have played, and continue to play, an important role in all aspects of national security. The convergence of technology and social media has generated opportunities for improved target audience communications and interventions, but also provides individuals who may seek to harm with the ability to communicate their own messages and ideologies around the world quickly and broadly. These opportunities, and the development and continued advances in cyber technologies including the Internet and social media applications and websites, present the United States Government (USG) and its allies with numerous intervention scenarios though there also are potentially grave risks. While these technologies help foster connections among groups of individuals, allowing for the spread of viral advertising, ideas, and memes1 as well as movements for political change, they may also have facilitated the emergence and extended the reach of violent extremist organizations (VEOs).

The main question guiding this inquiry is: What are the implications of cyber-based communications for theories of political mobilization and mass radicalization? This document seeks to explore cyber- related implications for key concepts underlying current models of radicalization and mobilization (e.g., norm generation and propagation, cultural and genomic adaptations, attitude and belief formation). It explores peer-reviewed academic research on the topic of political extremism, radicalization, and mobilization in light of advances in communication technology and the online environment. In addition, interviews were conducted with researchers to ensure that even yet-to- be-published research findings were included. This report builds directly on recent Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) projects pertaining to political extremism and countering violent extremism including the June 2012 SMA report entitled “Neurobiological & Cognitive Science Insights on Radicalization and Mobilization to Violence: A Review,” while drawing on the vast literatures and ongoing research of scientists in the fields of neurobiology, social and cognitive psychology, social and cognitive neuroscience, political science, anthropology, communication science, and other related disciplines.

5th Annual SMA Conference.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The 5th Annual Strategic Multi-layer Assessment (SMA) Conference was held at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland from 29-30 November 2011. The SMA program is prioritized by the Joint Staff and executed by ASD (R&E) RFD. The focus of the SMA Conference was on influence strategies of state and non-state actors as well as the impact of the social and neurobiological sciences on key aspects of national security. The conference also hosted special sessions on geospatial applications, influence and deterrence in cyber space, and complex adaptive systems. Each session was designed to draw on diverse perspectives and insights from across the United States Government (USG), industry, and academia as well as from around the globe.

The Joint Staff, in partnership with the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), has developed a proven methodology merging multi-agency expertise and information to address complex operational requirements that call for multi-disciplinary approaches utilizing skill sets not normally present within any one service/agency. The SMA process uses robust multi-agency collaboration leveraging intellectual/analytical rigor to examine factual/empirical evidence with the focus on synthesizing existing knowledge.The end product consists of actionable strategies and recommendations, which can then be used by planners to support Course of Action (COA) Development.

LTG Michael Flynn, Assistant Director for National Intelligence, provided the keynote speech that covered the changing threat environment, which is creating new demands on the intelligence community and requiring a critical look at the many dimensions of the complex, human-dominated world. He provided four core insights into this complex environment.

- The threat environment is highly asymmetric, amorphous, complex, rapidly changing, and uncertain.

- There is a greater need for speed and flexibility in US intelligence gathering and decision making

- Current analytic deficiencies arise from the Cold War structure and insularity of the intelligence community, complexity of the environment, and how we currently think about threats

- New thinking needs to consider populations as important actors (e.g., mobilization via social media, etc.) and the social and resource inequities and grievances that spawn conflict

A significant portion of the conference focused on soliciting and discussing the needs of the Combatant Commands (COCOMS) to inform how the SMA program can best support the operational community. The panel was moderated by BG Mike Nagata, JS J37 DDSO, and drew on the experiences and insights of various representatives from across the Combatant Commands. The panelists are listed below.

- BG Mike Nagata, JS, J37, DDSO (moderator)

- COL Carl Trout, JS, J7

- Mr. Aaron Meyer, PACOM

- CAPT Todd Veazie, SOCOM

- Mr. Marty Drake, CENTCOM

- LTC Gerald Scott, JS, J3

- Mr. Roger Baty, NORTHCOM

- LtCol Scott Tielemans, CENTCOM

- Mr. Juan Hurtado, SOUTHCOM

- Master Chief Dave Cooper, SOCOM

- LtCol (Dr.) Rob Renfro, CENTCOM

Several key themes emerged from the panel discussion.

- Issues and questions from the operational community must be well framed to ensure analytic responses meet the COCOMs’ needs. Answers are only as good as the question asked.

- The operation community needs tools and models to aid complex planning and decision- making. These tools and models need to be able to

- Deal with complexity and uncertainty;

- Incorporate various perspectives;

- Operate dynamically and across multiple dimensions;

- Be easily and quickly learned;

- Focus left of boom;

- Help operators to better understand others as well as ourselves; and g. Make information more digestible through better visualization.

- Officers need to be trained how to use social science tools so that they will feel comfortable employing these decisions and planning aids to maximize operational success.

- Solutions to complex national security issues, particularly with regard to population-centric challenges, should be sought from a broad community of potential contributors including academia, industry, think tanks, and other non-traditional sources. A community, or communities, of interest must be built and sustained.

- Cyber threats have the potential to alter the types of problems the operational community faces in the future. They are a potential game changer.

- Building and fostering personal relationships across militaries and governments is the key to success when operating left of boom.

The panelists agreed that programs, like SMA, that seek solutions to the nation’s complex strategic issues using rigorous, diverse analytic methods drawn from a large community of government and non-government contributors provide a template for 21st Century strategic thinking.

The Influencing State and Non-State Actors session consisted of a two-part introduction followed by three panels. The session’s objective was to explore and discuss the fundamentals of analytic approaches for deriving and assessing actions to influence and deterring state and non-state actors. The first part of the introduction explored the methodological and conceptual challenges of tackling an extraordinarily complex dynamic problem space that consists of a wide range of actors (e.g., nuclear powers, failing states, non-state organizations, virtual actors), U.S. objectives (deterrence, assurance, defeat, counter-terror, non-proliferation), competing interests, and anticipated and unanticipated effects. Maj. Gen. Joseph Reynes, AJFC, Netherlands, supplemented this conceptual discussion with a view of the real world practicalities of thinking about and conducting deterrence and influence operations.

Panel One, moderated by Mr. Pat McKenna, STRATCOM, reviewed recent efforts on behalf of various COCOMs to envision the complex system of state and non-state actors and their interests that must be considered in nearly any analysis in support of deterrence or influence operations. Discussion centered around critical, but often inadequately defined, basic concepts and language of deterrence and influence. Panel Two,, moderated by Mr. Dan Flynn, ODNI, focused on the practical questions of generating sufficient relevant data and the use of appropriate, creative analytic techniques (e.g., crowdsourcing, war gaming, simulation and computer-based modeling) for developing influence and deterrence operations COAs. Panel Three, moderated by Dr. Allison Astorino-Courtois, NSI, discussed the prospects for developing readily accessible tools and models to help operators tackle the dynamic threat environments faced by the U.S. while avoiding unfavorable and unintended consequences. Further discussion touched upon the real-world impediments to including modeling and other multi-input analyses in (non-kinetic) effects planning.

Mr. Pat McKenna summarized the key insights from Panels One, Two, and Three.

- The nation can prepare for the future, but it cannot predict it.

- Operational environments are much more complex today than they were in the past.

- The threat is constantly evolving and the threat environment is becoming more complex.

- The U.S. needs to be agile.

- No single model can capture all of the complexities; there is no universal method.

- Analysts are trying to provide insights not solutions.

- Ultimately, analysts, modelers, and planners are providing information to enhance decision-making.

Mr. McKenna then noted the challenges that arose throughout the discussions. These challenges are listed below.

- There is a need to focus on being left of boom.

- It is important to determine how to balance agility versus comprehensiveness.

- Investments need to be made in the analytic community even with shrinking budgets.

- It is crucial to have critical thinking people and utilizing multi-disciplinary approaches.

- There is a need to obtain more complete data and determine how to know if it is authoritative and unbiased.

- Authoritative data must be incorporated into models.

- Techniques that are not singularly focused must continue to be used.

- Deterrence must be balanced in terms of other forms of influence.

- The integration of multiple tools must occur.

- There is a need to determine if tools are valid and the proper ways to deal with uncertainty within these tools.

A session on Geospatial Applications for Population Centric Assessments, moderated by Ms. Elizabeth Lyon, OSD, and Dr. Bert Davis, United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), examined geospatial data, geospatial methods (including data collection), and geospatial applications for defining place including elements such as the physical and social environments and factors leading to understand stability and security in places that are either currently stable, transitioning, or in conflict.

Additional panels were held throughout the conference to provide further perspectives and insights. The panel on Implications of Recent Advances in Social, Cognitive, and Neurobiological Sciences to National Security, moderated by Dr. Diane DiEuliis, NIH and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), discussed cutting edge scientific research in the areas of political violence, radicalization, and deterrence. The panel examined how recent scientific discoveries might inform our understanding of violence in general and, more specifically, issues of national security relating to political violence. Dr. Bill Casebeer summarized the key findings and insights from the Neurobiology panel.

- Neurobiological research helps the operational community understand the mechanisms that underlie higher order phenomena

- The amygdala plays a key role in response to threats

- Emotional triggers can be subconscious

- Out-group members trigger more amygdala activation than in-group members

- Disinhibition contagion is a neurobiological process, which can result in friendly fire

- Leader fires first and releases the inhibition of others to use force

- Understanding neurobiological processes will help the DoD formulated Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) to limit collateral damage

- Narratives and stories are important psychologically and neurobiologically; they…

- Influence how one remembers things and helps humans make judgments about who it is permissible to kill

- Could have implications for influence campaigns

The panel on Influencing Violent Extremist Organizations (IVEO) Neurobiology Pilot Effort, moderated by Ms. Abigail Chapman, NSI, discussed results from the quick turnaround effort designed to provide a multi-method, multi-disciplinary exploration of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The panel on Influence and Deterrence in Cyber Space, moderated by Dr. William Casebeer, DARPA, addressed the core questions facing the operational community today with regard to influence and deterrence in cyberspace. The panel on Complex Adaptive Systems, moderated by Lt Col David Lyle, United States Air Force (USAF), examined the importance of understanding human complexity in the operational environment. The panel further discussed ways in which visualizations inspired by complex science innovations could help to combine and present vast amounts of complex data in new formats, helping the observer intuitively understand the key nodes, linkages, and dynamics of complex systems of all kinds.

The proceedings with all slides and videos will be posted on the SMA SharePoint site (https://nsiteam.net/x_sma/default.aspx). If you do not have an account, you can register for one by going to https://nsiteam.net/newAcct. If you already have an account and cannot recall your password, please visit this URL: https://nsiteam.net/reset.

Authors | Editors: Ackerman, G. (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism); Asal, V. (University at Albany, State University of New York); Canna, S. (NSI, Inc.); Davis, P. (RAND and Pardee RAND Graduate School); DeRouen, K. (University of Alabama); Helfstein, S. (Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point); Knopf, J. (Naval Postgraduate School); McAdam, M. (University of California, Berkeley); Pate, A. (University of Maryland); Pinson, L. (SAIC); Rethemeyer, K. (University at Albany, State University of New York); Sawyer, J. (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism); Young, J. (American University)

Executive Summary

The purpose of this project was to gain a better understanding of how United States Government (USG) actions influence violent extremist organizations (VEOs). It is important to understand how actions taken by the government to suppress a VEO might result in negative, unforeseen consequences such as making a VEO stronger or increasing its public support.

The work conducted by the project team, coordinated by Dr. Scott Helfstein at the Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point, is one component of a larger effort to better understand how VEOs are, or can be, influenced. The overall Influencing Violent Extremist Organizations (I-VEO) effort was conducted by the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) Office within the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). The SMA Office provides planning support to Commands with complex operational imperatives requiring multiagency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. Solutions and participants are sought across USG and beyond. SMA efforts are accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff and executed by STRATCOM/J-9 and DDRE/ASD (R&E).

The project team included the following contributors.

• Dr. Gary Ackerman, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism

• Dr. Victor Asal, University at Albany, State University of New York

• Dr. Paul K. Davis, RAND and Pardee RAND Graduate School

• Dr. Karl DeRouen, University of Alabama

• Dr. Scott Helfstein, Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point

• Dr. Jeffrey Knopf, Naval Postgraduate School

• Ms. Melissa McAdam, University of California, Berkeley

• Dr. Amy Pate, University of Maryland

• Ms. Lauren Pinson, SAIC

• Dr. Karl Rethemeyer, University at Albany, State University of New York

• Dr. John Sawyer, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism

• Dr. Joseph Young, American University

The objective of the I-VEO effort is to provide the Department of Defense (DoD) and its USG partners with a holistic understanding of intended and unintended effects of influencing violent extremist organizations that can be transferred to a usable analytic framework that inform decision-makers and planners. The resulting holistic analyses derived analytic confidence from the examination of sound theoretical knowledge, conceptual modeling, and testing in historical cases. The effort ran from February through October 2011.

The intended payoff of this project was a deeper, more reliable understanding of the secondary effects of U.S. government efforts to influence VEOs. The results of the I-VEO study will aid the Joint Staff and COCOMs at strategic and operational levels by providing a conceptual framework grounded in sound theoretical concepts and analyses (albeit, with large uncertainties). This report presents and integrates findings from portions of the overall project, namely: a review of theoretical hypotheses and the degree of empirical support that they enjoy; quantitative analysis of selected data relating to the hypotheses; new thinking on how to understand how influence works or fails to work; related models of human behavior; highlights from an integrative literature-based discussion of systemic theory; discussion of alternative approaches to both theory and empirical research; other sources of knowledge and insight; and implications for the body of knowledge.

For detailed information about any of the other core components, please contact Mr. Sam Rhem at Samuel.Rhem.ctr@js.pentagon.mil.

Conclusions

The results of this project do not produce an answer to the problem that the U.S. government and its allies face in incentivizing VEOs to abandon violence or punishing them for using violence and may be disappointing to some as a result. No amount of research or analysis can ensure that negative consequences will not arise from a given influence action. The costs and benefits of courses of action (COAs) must be weighed and this project hopefully provides some assistance to those responsible for assessing the range of consequences that arise from government action.

We hope that this project has made a useful contribution in compiling a list of (sometimes-contradictory) rules of thumb about how violent organizations act and react. The effort to synthesize and analyze data from a diverse set of fields that could pertain to violent actors helps identify different forces that might guide the response of influence targets, making it important to consider how different models of behavior could produce an array of outcomes. This may well be of use to the policymaking community tasked with assessing and making these difficult decisions. The military community already has a very sophisticated way to think through the utility of different actions, develop COAs, and adjudicate among them. This effort should fold into that process by raising questions about commonly held assumptions and providing rules of thumb for how violent actors behave.

In making decisions, the best one can expect is to 1) be informed about how similar actions have influenced similar groups, 2) be explicit about the how the actions actually trigger desired and undesired influence effects, and to 3) carefully think through how USG actions impact the target audience and other audiences. Ultimately, however, influencing VEOs is not a science. Actors and environments can be unpredictable. The most ideal course of action (COA) is one that produces the most good for the least negative consequences, recognizing that the cost-benefit is often a subjective assessment. No USG action will be free from negative consequences. The hope, however, is that those negative consequences will not be surprises, but rather events that are predicted, understood, and part of the planning assessment.

Author | Editor: Davis, P. (RAND)

Summary

In developing strategy to affect violent extremist organizations (VEOs) it is useful to take a “system perspective” to characterize the different elements of a VEO and the larger environment in which the VEO operates. It is also useful to think about an influence spectrum that includes efforts at one end to co-opt or induce and, at the other end, actions taken to punish now so as to deter later. Strategy, then, takes actions to promote different kinds of influences on different elements of the system with the intention of achieving desired effects, avoiding or mitigating unintended side effects, and being in a position to exploit unintended but favorable side effects.