SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

From the Mind to the Feet: Assessing the Perception-to-Intent-to-Action Dynamic

Author | Editor: Kuznar, L., Astorino-Courtois, A. & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

The purpose of From the Mind to the Feet is to open a much deeper dialogue about gauging intent than currently exists ei- ther in operational or academic arenas. It is intended to serve military and civilian defense leaders, deterrence and policy planners, and practitioners with a review of the basic concepts and state-of-the-art understanding of intent. It is organized into two sections: operational and academic perspectives on intent.

Operational Perspective: Basic Issues in Gauging Intent

The first section of this volume consists of four operational perspectives on intent. Kathleen Kiernan and Daniel J. Mabrey offer an enlightening description of law enforcement “street-craft” and explain how police methods of assessing an individual’s intent to offend can inform counterterrorist operations.

Harry Foster discusses the ways military planners typically assess the intent of state or nonstate leaders and then offers what he calls an “effects-based thinking” framework for measuring intent. Foster argues that this effects-based thinking combined with a betting methodology offers the best analytic framework for melding the analyst’s intuition (i.e., the art) with analytics to gauge intent.

Gary Schaub, Jr., widens the aperture to focus on how to gauge the intent of groups and large collectives such as nation-state and nonstate actors in the context of strategic deterrence. Schaub argues that a process to infer adversary intent on a continuous basis is needed so that a serviceable product is available to assist both in routine and crisis planning. He posits analysis of competing hypotheses as one method of achieving this goal that encourages debate and critical thinking about the adversary to prevent the typical intelligence errors of mirror imaging or groupthink.

Finally, John Bodnar outlines a new way of thinking about adversaries—and our relationship to them—in the twenty-first century.

Academic Perspective: Theory and Research in Gauging Intent

The second section of this volume consists of perspectives on intent that represent research and theoretical work in seven academic disciplines: anthropology, social psychology, international politics, social cognitive neuroscience, survey science, communications, and decision science.

In the first piece in this section, Lawrence Kuznar provides a comprehensive review of basic motivating factors recognized by anthropologists that help explain intent, including structuralism, interpretivism/symbolic anthropology, postmodernism, culture and personality, human behavioral ecology, and discourse analysis. It provides insight on intent as derived from socially shared systems of meaning and ideology.

Margaret Hermann concludes that learning how policy makers view what is happening to them is critical to understanding how governments are likely to act. With our unprecedented access to policy makers’ perspectives through 24-hour news cycles, new ways to measure and interpret these perspectives are being developed. Hermann’s assertions are tested by a case study in the following chapter.

Based on international relations research, Keren Yarhi-Milo provides analytic support for what we have always suspected: intelligence analysts and decision makers do not view the world or think about it in the same ways. Yarhi-Milo uses three test cases: British assessments of Nazi intentions prior to World War II, the Carter administration’s assessments of Soviet intentions, and the Reagan administration’s assessment of Soviet intentions in the final years of the Cold War.

Neuroscientists are actively unlocking the inner workings of the brain and revealing how goal-oriented, deliberative behavior interacts with emotive impulses to generate intentional behavior. In companion pieces, social neuropsychologists Sabrina Pagano and Abigail Chapman shed light on the latest in brain studies and the possible future applications of insights gained from neuropsychology for estimating and capturing an individual’s intent to act in a certain way.

Tom Rieger offers empirical evidence that large-scale instability-based violence and ideologically based violence are driven by different factors with different purposes. Iraq is used as an example to explain extremist violence and to illustrate how it is possible to win a war and lose the peace.

Representing social communication and messaging, Toby Bolsen discusses information-framing research and the gaps in the literature regarding the links between manipulations of perceptions and attitudes (framing) and short- and long-term behavior.

Finally, theories of intent abound, but the most difficult task is the measurement and assessment of this intangible. Elisa Bienenstock and Allison Astorino-Courtois address some contemporary efforts in actually measuring intent and propose a backward induction method for honing in on intent based on behavioral “probes” identified through decision analyses.

Contributing Authors

Elisa Jayne Bienenstock (NSI), John W. Bodnar (SAIC), Toby Bolsen (GSU), Abigail Chapman (NSI), Robert Elder (GMU), Harry A. Foster (Air University), Margaret G. Hermann (Syracuse U), Kathleen L. Kiernan (Kiernan Group), Daniel J. Mabrey (U of New Haven), Sabrina Pagano (NSI), Tom Rieger (NSI), Gary Schaub (Air War College), Keren Yarhi-Milo (Princeton)

Countering Violent Extremism: Scientific Methods & Strategies (2011 Edition)

.png)

Author | Editor: Fenstermacher, L. & Leventhal, T. (Air Force Research Laboratory).

[Note: There is a revised edition, released in 2015.]

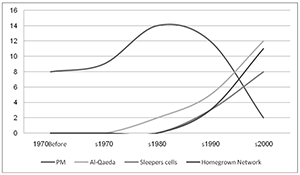

If there were a simple solution for countering violent extremism, a solution would have been found centuries ago. Countering violent extremism successfully requires a balanced approach between security-related strategies and initiatives and those that address the underlying motivations and causes for participation in, and support of, a violent extremist organization (VEO). These strategies and initiatives need to be based on nuanced understanding of the various aspects of violent extremism—not only the environments that are likely to spawn violent extremism and sympathetic supporters, but also

- The types of grievances that predispose those individuals to join and support violent extremist organizations and how they are framed in local contexts;

- the ways in which ideologies, media, messages, and narratives are used to instigate/radicalize, mobilize, indoctrinate, inform, or deradicalize;

- the social dynamics, capabilities, and resources of organizations that are violent or that are likely to become violent and their relationship with competitors (for attention, resources, etc.); and

- the underlying motivations of individuals (whether revenge, status, identity or thrill seeking1) who join violent extremist organizations.

No single solution or solution set generalizes to all groups or locations, necessitating continuous acquisition of information and updating/adaptation of assessments and strategies.

This paper collection, entitled, “Countering Violent Extremism: A Multi-disciplinary Perspective,” aims to provide new insights on the spectrum of solutions for countering violent extremism, drawing from current social science research as well as from expert knowledge on salient topics (e.g., development programs, cultivating community partners and leaders, conflict and deradicalization). So what is new? There is a large body of literature on terrorism and violent extremism, much of which focuses on developing a better understanding of the problem, including environmental and social/cultural factors and the role of ideology. This paper collection focuses less on root causes and more on solutions for risk management, disengagement (including delegitimization), and prevention of violent extremism. It also tackles the thorny issue of state terror, a subject that must enter any discussion of solutions for countering violent extremism. Ultimately, it is hoped that the paper collection can inform a better understanding of, and suggest sets of solutions for, motivating individuals and groups to desist from violence and preventing other individuals and groups from seeking involvement in movements/groups that seek to bring about change through violence.

Throughout the collection, there is an undercurrent of “do no harm”; that is, concomitant with suggestions for stopping or preventing violent extremisms, there are cautions an errors to avoid. These cautions implicitly ask the reader to think about things in a different way, in a way that avoids mirroring and simplistic assumptions of what others think or value and widens the timeframe in which we measure success or failure. Many goals related to countering violent extremism, especially disengagement/risk management and prevention require patience and a commitment for the long haul Patience is required to cultivate the right partners, support the building of institutional capacity and development of leaders, fund appropriate development programs to address local grievances, and support and amplify existing programs that support moderate discourse or develop new programs to deradicalize or disengage individuals from beliefs or attitudes. Likewise, messaging must match actions and must stem from someone who is credible and has a thorough understanding of the key ideological, political, and socio-cultural issues as well as the language, narratives, and symbols.

Some of the viewpoints in the collection are surprising and challenge popular conceptions. For example, in some cases, countering violent extremism requires doing nothing; well, not nothing exactly, but rather supporting/amplifying from behind (e.g., supporting social movements seeking governance change) or supporting other leaders, organizations, or states in leading initiatives. A prime example of this is the events of the Arab Spring, which yielded the inherent lesson that, in regions with social injustice and governance grievances , and political opportunity, social movements can and will emerge that motivate change virtually on their own. Another example where a supporting role is often called for is in implementing delegitimization strategies. Delegitimization involves the initiation of a discourse questioning the legitimacy of the violent extremist organization including their performance in other assumed roles/functions (e.g., shadow government, rule of law). This questioning is often best done by others who are more credible, knowledgeable, and steeped in history, ideology, narratives, and culture.

The Crown Prosecution Service defines violent extremism as the “demonstration of unacceptable behavior by using any means or medium to express views which foment, justify or glorify terrorist violence in furtherance of particular beliefs”2 including those who provoke violence (terrorist or criminal) based on ideological, political, or religious beliefs and foster hatred that leads to violence. Thus, countering violent extremism is something that must address instigators; however, first, countering violent extremism involves understanding and countering the ideas that leverage emotions, narratives, and ideologies that impel violence. Countering violent extremism is not the same thing as countering an ideology. This is not to say that ideology is not important or can be ignored. Current research points to ideology as a framing device or tool to rationalize or impel actions. Some believe that a group ideology is effectively an appliqué on top of an ideology, using the ideology for reinforcement and justification or, said another way, “religion and questions of identity (are) interwoven with questions of resources and political economy.”3 Success requires decoupling religious and political ideologies and acknowledging and addressing aspects that can foster the behavior changes we ultimately seek.

- This collection of papers yielded several insights. It is best to seek a balance between reflexive (security based) and reflective (addressing grievances, motivations) actions. Right now, solutions are overly focused on reflexive actions and thus actually create more of the problem we are trying to solve.

- Violent extremist organizations are effectively systems; thus, solution sets must contain tailored (kinetic and/or influence related) solutions for each system component (foot soldiers, instigators, leaders, supporters, logisticians, etc.) in ways that are appropriate for the culture, language, locality/region, and underlying motivations.

- Decision makers should avoid missing the “forest for the trees” by overly focusing on ideology. Local grievances trump global issues and need to be understood and addressed.

- Messengers are only effective when perceived as credible and knowledgeable; simply, if you are not credible, you should not be the messenger. Messages stick when they resonate with grievances, motivate behavior when they provoke affect, and persuade when the actions of the messenger match the words. Our adversaries understand this and employ this understanding in their messaging; thus, our counter messaging should take a “page from the same book.”

- Partners, chosen wisely, are critical in countering violent extremism with, in many cases, our partners in the lead. Without ownership, solutions will not be as successful or lasting,

- Many good things (messaging in Arab popular culture, music, grassroots deradicalization efforts), are already going on to counter violent extremism around the globe. Success, in many cases, will come from amplifying and supporting what is already working,

- Focus on small, achievable wins over the long haul (e.g., disengagement or risk management versus deradicalization, delegitimization of strategic objectives or outcomes).

- Delegitimization can be effective in exploiting vulnerabilities and inconsistencies (e.g., disconnects between the fantasy of violent extremism and the reality).

- Our timeframe for countering violent extremism needs to lengthen and the resources for strategies whose payoff is not immediate (e.g., development) must increase. Success will come with sustained efforts with appropriate partners, resources, and (adaptive) strategies.

The collection is organized in four sections, each of which contains papers that provide a tomography for violent extremism, highlighting factors that engender violent extremism and highlighting some of the options of the spectrum of solutions from prevention to changing the (violent) behaviors of already radicalized individuals or groups. The first section provides perspectives on factors and processes underlying violent extremisms and motivates the development of multi-layered tailored strategies. The second section focuses on the prevention of violent extremism: who is at-risk, what is important to many vulnerable populations, who should we partner with, and a variety of proposed solutions. The third section addresses solutions for affecting support for violent extremism, including delegitimization and support or amplification of existing programs (popular culture and music). Finally, the fourth section provides insights on solutions and attributes for solutions whose objective is changing the behavior and/or attitude of violent extremists including deradicalization/disengagement, deterrence, and coercion.

Contributing Authors

Ziad Alahdad, Latefa Belarouci, Cheryl Benard, Curt Braddock, William Casebeer, Steve Corman, Paul Davis, Karl DeRouen, Diane DiEuliis, Evelyn Early, Mehreen Farooq, Dipak Gupta, Tawfik Hamid, John Horgan, Qamar-ul Huda, Eric Larson, Anthony Lemieux, Hedieh Mirahmadi, Robert Nill, Paulina Pospieszna, Tom Rieger, Marc Sageman, John “Jack” Shanahan, Anne Speckhard, Troy Thomas, Lorenzo Vidino.

Concepts & Analysis of Nuclear Strategy Theory Team Framework Report.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc).

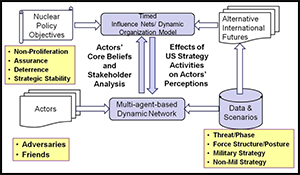

This paper reports the theoretical review and framework development conducted by the STRATCOM/J-5 “Concept and Analysis of Nuclear Strategy (CANS) Theory Team. It reports the theoretical review and framework development with two goals in mind:

- Framing the problem space surrounding U.S. deterrence, assurance, defeat, counter-proliferation and strategic stability policy objectives in light of varying threats, international environments, and adversary types.

- Developing an intellectual framework within which the alternative analytic and modeling techniques might be evaluated.

The CANS project is intended to examine the utility of alternative analytic techniques for assessing nuclear force attributes and sufficiency under a variety of changed conditions. This report captures the essence of a continuing discussion rather than a final assessment of the problem space.

This effort is designed to inform debates in this topical area and to facilitate the related CANS modeling efforts that follow. It is important to note that, as with the entire CANS effort, the theory team was not intended to review or produce policy or force structure recommendations.

More than twenty years after the common dating of the “end” of the Cold War, US military planners and policy analysts continue to grapple with ways to conceptualize and analyze the sufficiency of our nuclear forces. Specifically, their ability to accomplish major policy goals in a multi-polar world where diverse actors – from “major powers” to those that have been all but disregarded – now constitute significant threats to US and allied interest. Not only is it unclear the extent to which traditional models of nuclear strategy still apply, but efforts to extend them run up against an expanded array of potential threats, types of actors, and foreseeable international environments.

The Concepts & Analysis of Nuclear Strategy (CANS) project undertaken for US Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) was tasked to examine the utility of alternative analytic techniques for assessing nuclear force attributes and sufficiency under a variety of changed conditions. It was a nine-month effort during which major tasks were divided among three teams:

- Theory Team: Responsible for reviewing existing nuclear strategy theory, defining terms and establishing an intellectual framework for conducting the study.

- Analysis Team: Composed of war gamers, strategic gamers, computational and decision modelers, and qualitative researchers who addressed some of the key outstanding questions as they conducted a “deep dive” demonstration of several alternative analytic approaches to the study of nuclear strategy.

- Integration Team: Tasked with attempting to integrate the outputs generated by the first two teams into a series of conceptual models and a cohesive framework to assist planners and policy analysts as they think through some of the difficult topics they will face in coming years.

The following key questions were addressed by the Theory Team’s approach as well as the various deep dive efforts undertaken for the CANS project:

- How do we set up the analytic community to address the next round of arms control relevant to our nuclear forces and strategy?NSI: DAT model

- NSI: ATOM model

- Monitor 360: Crowdsourcing

- DNI: game

- How do the attributes of a potential force posture relate to deterrence, assurance, defeat, strategic stability and counter-proliferation?

- NSI: ATOM model

- Carnegie Mellon University Dynamic Network Analysis

- George Mason University: Pythia

- What are the force structuring questions associated with the anticipated thrusts of upcoming arms control negotiations?

- DNI game

- How should tradeoffs between force attributes be considered?

- NSI: ATOM model

- Do changes in US targeting doctrine change our abilities to deter adversaries and assure allies?

- USAF Game

- Monitor 360: Crowdsourcing

- Carnegie Mellon University: Dynamic Network Analysis

- George Mason University: Pythia

- How should we assess risks and trade-off relationships relative to nuclear force posture and modernization decisions? Monitor 360 Crowdsourcing

- George Mason University: Pythia

This report outlines the theoretical review and framework development conducted by the CANS Theory Team. The Theory Team Supporting Documents compiles individual pieces written by Theory Team members that focus on specific elements of the framework and their interrelationship. These documents capture the essence of a continuing discussion rather than final judgments, and are best viewed as a “living” product that reflects Theory Team discussions. Both have been refined and amended over the course of the project. The Framework Report and Supporting Documents were designed to inform debate in this topical area, and to enrich and facilitate the Analysis Team’s modeling efforts.

The Theory Team was charged with two goals: first, to frame the problem space surrounding the U.S. policy objectives of deterrence, assurance, defeat, strategic stability, and counter-proliferation in light of varying threats, international environments, and adversary types; second, to develop an intellectual framework within which the alternative analytic and modeling techniques might be evaluated.

It is important to note that, as with the entire CANS effort, the theory team was not intended to review or produce policy or force structure recommendations.

This report represents the Theory Team’s approach to mapping the scope of the nuclear strategy policy space. However, over the course of this effort it became clear to members of the Theory Team that this mapping process generated further questions, as well as answers. Even now, a number of outstanding issues and theoretical issues challenge our understanding of this problem space. Some of these are enumerated in the “Way Ahead” section at the end of this report.

The Framework Report is organized as follows: A broad view of the problem space associated with assessing nuclear force structure and posture – what the team has called the Problem Space Vortex – is introduced. In essence the Vortex imagines the complex collection of factors that define the space within which force posture and structure trade-offs and decisions must be made. This is a first step in articulating a credible, useful way of expressing the value of US military capabilities in deterring or defeating adversaries, assuring allies, maintaining strategic stability, and countering potential nuclear proliferation. This is followed by discussion of the 5-Dimensional intellectual framework that was used in this project for organizing and cataloguing alternative analytic approaches according to the types of contexts to which they apply. Each of the five dimensions–policy objective, actor type, threat, world “future”, and operation/conflict phase - is discussed individually and multiple models for thinking about the different dimensions are provided. The report concludes with an outline of the overall CANS project. This involved two major activities. The first built on the framework tables that are the culmination of this report (see page 23) to identify pertinent questions and the relevant analytic techniques for addressing them. Simultaneously, the Analysis Team – made up of USAF, USN and DNI war gamers, a George Mason University-led multi-modeling team, NSI decision analysis, and Monitor 360 Crowdsourcing Non-U.S. SME sub-teams -- worked to produce “deep dive” examples, exercising these approaches specifically for the USSTRATCOM problem set.

A Guide to Analytic Techniques for Nuclear Strategy Analysis.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B. & Popp, G. (NSI, Inc).

The Concepts & Analysis of Nuclear Strategy (CANS) project undertaken for US Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) was tasked to examine the utility of alternative analytic techniques for assessing nuclear force attributes and sufficiency under a variety of changed conditions. The CANS software developed during this effort is designed to enhance the planning process by guiding the analyst through the process of selecting appropriate alternate analytic techniques.

Using the CANS software1, an analyst first starts with a question. They then select the appropriate level of analysis and the availability and type of data for answering that question. The application highlights the analytic techniques that may be used to help answer the question. The analyst can read a brief description of the technique and the resources are required to implement a research design using that technique. The analyst may also read an in-depth write up of how to use the technique in the context of nuclear deterrence, and in some instances examples of the application of the technique to the CANS problem space. This guide is a compilation of all the write-ups produced for the CANS software. These write-ups fall into two categories:

PART 1: Generic technique write-ups

These focus on a particular analytic technique. These provide the reader with a thorough introduction to a specific analytic technique. They are intended to provide enough information to enable the reader to determine the utility and practicality of that technique to problem they wish to examine. They are not intended as a guide for the application of that technique.

At the end of each write-up is a requirements section that discusses the data, time, tools, cost, skill set and expertise required to implement such a technique. For the purposes of comparison a coding scheme (outlined below) was developed to provide user with a way of comparing between different techniques.

PART 2: Examples of the application of modeling techniques to the CANS problem space

As part of the CANS effort various modeling and analysis projects were undertaken. These were designed to both demonstrate the utility of a specific technique to the nuclear strategy context and provide further insight into relevant questions. As well as providing detailed reports of their efforts, contributors to the CANS modeling effort also provided brief write- ups of their work for the CANS Software.

Influencing Violent Extremists: Focus on Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)

Author | Editor: Desjardins, A. & Adelman, J. (NSI, Inc).

In 2010 the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment (SMA) office saw a need to bring academics, practitioners, and individuals from all branches of the United States government together to discuss the current research and debate issues surrounding extremist violence: Defining a Strategic Campaign for Working with Partners to Counter and Delegitimize Violent Extremism (CVE) and the Neurobiology of Political Violence. The findings from the two conferences clearly indicated that a detailed examination of a violent extremist organization from a multi- method approach was required in order to begin down the path of understanding.

The CVE workshop was held from 19-20 May 2010 at Gallup World Headquarters in Washington, DC. The workshop focused on strategic communications and violent extremism and was designed to inform decision makers and was not intended as a forum for policy discussion. The workshop emerged from an SMA- and AFRL- sponsored white paper entitled Protecting the Homeland from International and Domestic Terrorism Threats: Current Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives on Root Causes, the Role of Ideology, and Programs for Counter-radicalization and Disengagement. The key insights and findings of the CVE workshop are as follows:

- Violent extremism cannot be reduced to one singular or simple cause

- The difficulties of pursuing deradicalization and delegitimization are numerous. The question to ask is if this is an appropriate or attainable goal

- Multi-perspective, tailored approaches are key to effective counter-terror strategic communications

- The ways the US uses vocabulary and themes is critical to success of its strategic communications

The Neurobiology of Political Violence: New Tools, New Techniques workshop hosted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), United States Strategic Command (STRATCOM), the Joint Staff, and the Strategic Multilayer Assessment Office (OSD) in Bethesda, MD from 1-2 December 2010. The workshop facilitated a broad discussion of the current state of the art within the related fields of neuroscience, neurobiology, and social psychology as it relates to deterring political violence. While most panelists emphasized the prematurity of applying current research to real world problems within the national security and homeland defense space, they all agreed that the tools of neuroscience and related fields would serve to better inform current deterrence and messaging strategies. The key insights and findings from the workshop are below:

- Neuroimaging (e.g., MRI) has great utility and provides added insights devoid of self- report biases.

- In-group/out-group receptivity to reconciliation has a neurobiological basis and can be modified by rhetoric.

- New tools and techniques are emerging.

- Culture and environment influence behavior and brain function.

- It is critical to continue basic research in this area.

The Influencing Violent Extremist Organizations (IVEO) Pilot Effort was organized by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Office in the Department of Defense (DoD) and supported by the Joint Staff (J-3), Strategic Command (STRATCOM), and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. The Pilot Effort fits into the broader IVEO effort, which has the objective of first improving the United States Government’s (USG) understanding of potential unintended consequences of influence actions against VEOs and, second, suggesting principles for planning influence actions that mitigate potential negative effects and exploit potential opportunities to produce intended effects.4 The Countering Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs) Pilot Effort: Focus on Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) effort was a multi-method, multi-disciplinary exploration of the selected VEO. AQAP was selected as the focus of the pilot effort due to its continued threat to the United States.

Social science has provided an extant literature surrounding the who, what, and why of violent extremist organizations. The who and the what are the easy parts. It’s really the why at a fundamental human level that—even after decades of research, including theorizing, empirically testing, and cautiously observing—still has social scientists in disagreement and searching for answers. This pilot effort provided a unique approach to investigate not only the why, but also the how, in violent extremist organization recruitment. Where does support come from, particularly global support that goes above and beyond a local connection? Assembling the top researchers in this field to discuss more theories has been done before, and frankly, is not enough to move us to the next level of understanding and providing counterstrategies. In this pilot effort, we brought the best and brightest in to answer one question: given your area of expertise, what can we possibly do to counter recruitment in violent extremist organizations? From there, we aimed to synthesize these efforts into one coherent package that may take us beyond simple theoretical strategizing. Across the fields of social psychology, social neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, political psychology, and communication science, this work is truly an interdisciplinary effort.

This quick turnaround effort began in early March and culminated in early August, with the final report delivered late-September of 2011. Initially, each participant worked independently on their research. In late-July, all of the participants came together to begin integrating their findings across disciplines along with AQAP subject matter experts and practitioners to discuss the results and identify any gaps. The end result here is the final culmination of these efforts.

Selected Chapters:

- Social Identification, Influence, and Why People Join AQAP (A. Adelman & A. Chapman)

Attribute Tradeoff Model (ATOM): Model and Software Documentation.

Author | Editor: Bragg, B., Orlina, E. & Salwen, M. (NSI, Inc).

The ATOM model seeks to link discrete and measurable force posture attributes (such as flexibility, sustainability and reach) to such broad concepts as deterrence and counter proliferation in a systematic and meaningful way.

Given New Start, the Administration’s interest in “nuclear zero” and a budget-constrained environment, analysts are likely to receive greater numbers of requests for comparison of the capacity of various force postures and structures to achieve nuclear policy goals. At present, no theoretically grounded and systematic method exists for comparing how well specific (attribute- based) force postures support specific policy objectives. In the nuclear context, the central policy objectives identified by the Concepts and Analysis of Nuclear Strategy CANS project are strategic stability, counter proliferation, deterrence, assurance and defeat.

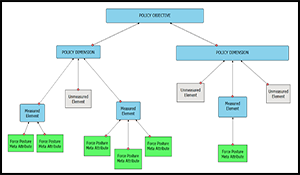

ATOM relies on an assessment process that first analyzes a problem structure from complex concepts to more basic and directly measurable elements and then synthesizes the evaluation of those basic elements through the structure so that alternatives may be assessed not only on the basics, but on the high-order concepts as well. The first challenge raised by this task is determining how to link discrete and measurable force posture attributes (such as flexibility, sustainability and reach) to such broad concepts as deterrence and counter proliferation in a systematic and meaningful way. ATOM achieves this by creating a theoretical model that decomposes these high-level policy objectives into their basic elements, and then links individual force posture attributes to these specific elements (see Figure 1). The theoretical model draws on an extensive academic and policy literature to determine the set of elements for specific policy objectives.

The second challenge is to derive assessments with respect to high-level concepts such as policy objectives from the evaluation of the more basic elements of the model decomposition such as force posture attributes. There are many algorithms designed to aid in this process—what is often referred to as multi-attribute decision analysis—and ATOM includes two that have been instantiated into its software. A fuller description of these algorithms appears below in the ATOM Software Overview section of this document.

The ATOM software is composed of two parts: (1) a Java-based Structure Authoring Tool that provides users a graphical interface for decomposing the problem space and; (2) An R-based Decision Support Engine (DSE) that aggregates the assessment of force posture alternatives through to policy objectives, cost and risk. In essence the software takes the model and represents it graphically in the form of tree diagrams that clearly map the breakdown of individual policy objectives and the link between policy elements and force posture attributes. This relational information is then used by the DSE to assess the relative strengths of specific force postures for achieving individual or multiple policy objectives.

ATOM, as presented in this guide, therefore, should be thought of as two related, but distinct products. The first is the theoretical model, which is specific to the nuclear policy context; the second is the software, which, although developed to deal with this specific model, is in itself content-free. The Structure Authoring Tool and DSE can be used to render a detailed decomposition and analysis of any problem space of interest to the analyst, from nuclear policy to which motorcycle to buy. It is our expectation that for analysts interested in the nuclear policy problem space there will be very little need to change the current instantiation of the theoretical model. Two possible exceptions to this would be modifications of the edge weightings (which are currently all set at 1.0, implying equal weighting of each child node) and additional linkages between specific policy elements and force posture attributes. The majority of input will be done in the DSE, with the comparison of specific force postures (represented by their ratings across the 13 meta attributes taken from STRATCOM’s existing analysis structure) across different combinations of policy objectives.

Perspectives on Political and Social Regional Stability Impacted by Global Crises – A Social Science Context.

Author | Editor: Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff), Sotirin, B. et al. (USACE-HQ, CERD).

Cooperative security, stability operations and irregular warfare missions require a better understanding of the complex operational environment, notably through rich contextual understanding of the factors affecting stability. Further assessment, policy, and planning need to consider factors associated with institutional performance (community organizations, government ministries, legal structures, etc.) based on how societies emerge, develop, and function, as well as attributes that provide resiliency and flexibility.

Today, stability experts are faced with a new environment in which the world is highly interconnected, change is very rapid, and threats are multifaceted; all of these pose very different challenges to the US Government (USG). The current financial situation underscores both the rapidity and global extent of economic collapse, and it has exacerbated problems in other areas. Solutions in one area can have first-, second-, and third-order effects in other areas; these effects can be both positive and negative. Global average food prices increased by more than 80% during 2005-2008, sparking food riots in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Former Soviet Union, and Central and South America. Contributing factors are complicated; for example, shifts in food demands may be contributing to the food price increases, as increasing use of food crops for bio- fuels and increasing demand for protein-rich diets dramatically decreases efficient use of grain calories. Estimates of future water availability are alarming, and while earthquakes often impact manmade water management structures, reports also suggest that geophysical changes caused by large dams may have triggered earthquakes, including China’s 7.9 magnitude earthquake last year along a fault near the Zipingpu Dam and Reservoir that left 80,000 people missing or dead. In addition to food and water issues, severe weather events and climate change, shifts in demographics, increasing energy demands, pandemics, and threatened usage of nuclear weapons are threats that individually, or worse, in combination, can significantly increase the fragility of world stability.

While in today’s increasingly interconnected world, global crises and unstable regions pose an acute risk to world security and could provide unforeseen circumstances ripe for manipulation and exploitation, these same threats can serve as rallying instruments, catalyzing disparate groups to work in concert to develop coordinated responses and preparedness mechanisms. This coordination can also result in development of negotiation venues for other issues. First-, second- and third-order effects can have positive impacts. In addition to the factors identified in the frameworks above, other dimensions of consideration include (1) institutional performance (community organizations, government ministries, legal structures, etc.) as a function of how societies emerge, develop, and operate, and (2) attributes that provide resilience and flexibility.

So the lingering question remains, where will the next occurrence of regional instability be that requires U.S. intervention? How should we shape the structure of our future force to respond to such instability? This white paper brings some of best minds together to examine the following aspects of this challenging problem:

- ? Individual factors impacting regional stability

- ? How these individual factors can combine to create tipping points that drive significant regional instabilities

- ? Approaches to forecast and anticipate where future instabilities may occur to give our warfighters an unfair advantage in the future.

Collecting the Best Ideas

To capture the breadth of this issue, this paper examines issues ranging from political, infrastructural, demographic, economic, resource-related, climatologic, energy-related, epidemiological, sociological, and analytical issues as they impact regional stability. Decision makers are dealing with an evolving situation in which societies are increasingly interconnected; changes occur rapidly, often with unexpected consequences; and threats to stability are complex. This white paper is a comprehensive compilation and assessment of complex issues influencing regional stability by a diverse group of authors that discuss the assessment of regional stability through the lens of crises in food, water, changing climate, energy, economy, demographics and epidemics. These articles, some of which have been previously published, provide critical insights into factors and tools that can apply to this complex challenge. Contributors to this white paper have provided a rich analysis of the factors affecting stability, as well as new perspectives based on careful study and experience germane to today’s issues. This compilation yields an overarching view of regional stability as it impacts global and regional crises. Through detailed citations of the scholarship and current thinking throughout their communities, the authors make a compelling case for how multiple factors can coalesce to result in radical impacts on regional stability.

Bringing Wide-ranging Ideas Together

The organizational approach used to bring together the wide-ranging factors associated with stability is analogous to a wheel. At the hub, the central support, we examine the nature of stability and state building. What makes it work? This paper outlines the key aspects of functioning states, examines how they contribute to the good of all, and defines how they resist threats and provide stability.

Emanating from the hub are seven enablers of stability: demographics, economics, water, changing climate and weather, energy, food, and epidemics. Each of these articles discusses the relationship that enabler has on the stability of a society.

The rim of the wheel is a series of articles describing possible quantitative and integration methods coupled to social science modeling approaches. These approaches provide potential means to use existing and emerging information to forecast regional instabilities. The “tread” of the wheel is comprised of case studies in social science modeling. These articles provide a context and examples of unique challenges in predicting trends in social sciences.

Bringing Order to a Complex Problem

The factors in the frameworks discussed above form components of a complex system that interacts in dynamic nonlinear ways and has significant emphasis on social systems. It has become sometimes painfully obvious that evasion of independent consideration of these factors can hinder pursuing outcomes of national importance. Accordingly, the USG has considerable interest in descriptive models – with substantial attention and investment in a wide array of social science models in recent years – developed to inform a more comprehensive assessment of current security conditions and to enlighten potential future security outcomes that often ignore geo-political boundaries, that are insensitive to cultural issues, elude legal categorizations and/or expand beyond national economic conditions.

Assessment of regional stability needs to consider indicators associated with political, social and institutional performance based on how societies emerge, develop, and operate, as well as attributes that provide resilience and flexibility. Identifying geopolitical and socio-cultural indicators that target a confluence of factors, and establishing trigger thresholds may prove as important as defining the individual factors themselves. At the same time, assessment must also consider indicators associated with drivers of instability and conflict (economic decline/shock, criminalized security forces, environmental degradation, struggles for absolute power, etc.). We anticipate exploring multiple social science theories, research methods, and well-known quantitative/statistical analysis techniques (cluster analysis, nodal analysis, cross-correlation, and factor analysis) in this white paper to (1) independently select relevant indicators (climate change/change of weather, economy, water, food, pandemics or epidemics, energy), (2) operationalize and validate indicator coding schemes, (3) clarify interdependencies across indicators (impact of water policy on energy, health and economy), and (4) regroup indicators by looking at a confluence of factors, priorities and contributing factors and drivers of conflict and rallying mechanisms. Finally, assessment should function from an asset-based perspective that is focused on indigenous capabilities, perceptions, systems, interactions and activities at multiple levels, at multiple stages, and accounting for variability and rate of change. The result of the assessment should enable operators to understand what conditions exist, why they exist, and how best to transform them.

This white paper provides a comprehensive examination of the factors that influence regional stability. Points to investments and initiatives that will likely improve our ability to predict the consequences of crisis on regional stability can help minimize the threat of instability. Through the analysis of multiple social science theories, research methods, and established quantitative and statistical analysis techniques, this white paper, Perspectives on Political and Social Regional Stability Impacted by Global Crises - A Social Science Context, provides a significant step along the path to resolving the complex problems critical to the future security of the U.S.

This edited volume, consisting of short contributions (5-7 pages each), will describe definitions of stability, will examine assessment approaches, and will extend to encompass strategies for tailored assessment and planning.

Clare Lockhart (Section 1) addresses the significance of “Stability and State Building.” This paper describes how functioning states are a vital piece of global architecture and that as such they not only provide critical resistance to a variety of threats, but they also contribute to the collective global goals and stability in the 21st century.

Philip Martin of UC-Davis (2.1.A) reviews International Migration. The number of international migrants, defined by the UN as persons outside their country of origin a year or more, for any reason and in any legal status, more than doubled between 1990 and 2010. Current default policy is to manage what is often seen as out-of-control migration and by adjusting the rights of migrants, leading to conflicts over human rights. Martin’s paper analyzes long-term factors affecting migration patterns, including aging in industrial countries, rural-urban migration that spills over national borders, and the migration infrastructure of agents and networks that moves people.

Jack Goldstone (2.1.B) continues this theme with “Demography and Security,” in which he discusses the five major demographic trends likely to pose significant security challenges to the majority of developed nations in the next two decades. He notes that problems will be caused not by the overall population growth, but by the population distortions, in which populations grow too young or too fast, or become too urbanized.

In “Demographic Security,” Elizabeth Leahy Madsen (2.1C) reviews findings regarding population and two security issues—outbreaks of civil conflict and level of democratic governance—at the global scale. The theme of her paper is that population influences security and development, and it is an important underlying variable in global stability because of its interactions with other factors.

David Richards and Ronald Gelleny (2.2.A) address the relationship between banking crises and domestic agitation/internal conflict in “Banking Crises, Collective Protest and Rebellion.” They examine a dataset of 125 countries for the years 1981 to 2000 and find banking crises to be systematically associated with greater levels of collective protest activities such as riots, anti- government demonstrations, and strikes.

An overview of work done at the Joint Staff J-5 is outlined by Peter Steen (2.2.B) in “Economics and Political Instability within the Global Economic Crisis.” This paper provides a strategic national-level understanding of the ongoing global economic crisis, as well as investigates the relationship between economics and political instability within that context.

Jerome Delli Priscoli (2.3.A) of the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers discusses the role of water and its relationship to international stability with “Water & Security: Cause War or Help Community Building.” He posits that the water and security debate is driven by our notions of scarcity, and that ultimately, the strategic aspects of water lend themselves to finding means for cooperation rather than conflict.

An interagency team - Olsen and White (USACE), Brekke and Raff (US Bureau of Reclamation), Kiang and Turnipseed (USGS) and Pulwarty and Webb (NOAA) - representing the two largest water resources operating agencies (USACE and Reclamation) and two major water resources data and science agencies (USGS and NOAA) (2.3.B) continue the water dialogue in “Water Resources.” Their paper describes the multiple factors that can impact and stress water resources. Due to those interactions, solutions to water resource problems should follow a comprehensive approach that integrates multiple objectives across the proper spatial and temporal scales with all relevant stakeholders participating in the decision-making process.

In "Water Security and Scarcity: Potential Destabilization in Western Afghanistan," Alex Dehgan, and Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (2.3.C) offer a water resources case study. The paper highlights the implications of plans for upgrading and developing Afghanistan’s water infrastructure in the Helmand River watershed. While crucial to the social and economic development of Afghanistan, these plans will also impact transboundary water flow and as a result, Afghanistan's relations with Iran.

In “Maintaining Geopolitical and Social Stability throughout a Global Economy in an Era of Climate Change,” James Diaz (2.4.A) describes the uniform agreement in the international scientific community that the earth is warming from a variety of climatic effects. Ultimately, this change will have far reaching impacts on human health and public safety. Diaz believes the challenge for the U.S. will be to assume leadership in maintaining geopolitical and social stability throughout the global economy in an era of climate change.

Kenneth S. Yalowitz and Ross A. Virginia (2.4.B) address the role of the Arctic in the changing climatic environment in “The Arctic Region: Prospects for a Great Game or International Cooperation.” Their theory is that the pace of ecological, political, social, and economic change in the Arctic region is accelerating due to the warming climate. The paper evaluates the prospects for contrasting outcomes in the Arctic region: a return to international power politics as states seek to claim Arctic energy, extend continental shelves, and enforce their wills through military means versus the emergence of increased international cooperation around environmental protection and sustainable development.

“Changing Climate Impacts to Water Resources: Implications for Stability” is authored by Kathleen D. White, J. Rolf Olsen, Levi D. Brekke, David A. Raff, Roger S. Pulwarty, and Robert Webb (2.4.C), all from the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers and discusses climate change in the context of water resources, including the potential implications for stability issues. They argue that water resource managers are already accustomed to dealing with changes and therefore offer a potential resource to utilize for the larger issue if they are prepared to act quickly. The authors propose a strategy encompassing both the potential for increased conflict over water and increased cooperation by water resources managers to enhance planning for stability.

An introduction to the role of energy begins with “Energy, Africa and Civil Conflict: What Does the Future Hold?” by Richard J. Stoll (2.5.A). Stoll notes that Africa will likely become increasingly important to the U.S. as a source of resources, including oil. However, Africa is also rife with civil conflict. Ongoing civil conflict makes it very difficult to establish or continue the exportation of natural resources. Therefore, it is in the U.S.’s best interest to address the issue of civil conflict in Africa.

Douglas J. Arent (2.5.B) continues this topic of Energy with “Energy: A National and Global Issue,” and states that new energy pathways are a necessity to balance the increasingly complex policy goals of accessibility, environmental concerns, geopolitical issues, and affordability. Continuing reliance on geographically concentrated oil and natural gas to feed the ongoing demand will threaten international energy security.

Jeffrey Steiner and Timothy Griffin (2.6.A) address the role of food in relation to the larger picture of Stability in “World Food Availability and Natural Land Resources Base.” Steiner and Griffin note that there is a need to consider how changing population and wealth patterns will not only impact food availability and consumption patterns, but also our inter-related needs for energy and water. This is increasingly important in relation to the Earth’s finite land mass.

Donald Suarez (2.6.B) follows with “Food Production in Arid Regions Due to Salinity.” He discusses the issue of the water supply, the impact of salinity, the potential for water reuse—both of irrigation drainage and municipal waste water—and utilization of saline waters for crop production. Improvements in irrigation practices, investment in new technologies, and development of salt-tolerant plant varieties may enable these regions to utilize more abundant brackish and saline waters for irrigation and may minimize degradation of fresh water supplies.

The discussion of Epidemics begins with “Epidemics: A Thumbnail Sketch of the Past, Present and Future,” by Debarati Guha-Spair (2.7.A). Disease outbreaks have significant impacts on factors that are critical for national and international stability. There are clear disparities between rich and poor nations and their abilities to react and control the situation. Balancing policies to address the problems will also be a challenge for global disease control.

The Epidemics discussion continues with “Infectious Disease and Social Instability: Prevent, Respond, Repair,” by Daniel Strickman (2.7B). The effects of infectious diseases on social instability can be devastating and society’s ability to prepare and respond to an epidemic can offer social stability. The concept of Integrated Disease Management is presented as a construct to mitigate the societal impacts of infectious disease using the functions of risk assessment, surveillance, prevention and control, and sustainable support.

The role of social science modeling and its approaches to analysis is presented in Section Four. Victor Asal and Steve Shellman (3.1) begin with “Analyzing Political & Social Regional Stability with Statistics: Challenges and Opportunities.” They provide an overview of some of the research on the causes of stability and instability done using statistical analysis. A discussion of the efforts made in the area of forecasting is presented, as well as the challenges of statistical analysis related to issues of data and method.

Larry Kuznar (3.2) presents the anthropological view in “The Social Stability of Societies: An Anthropological View.” He notes that instability does not appear overnight and that a longer term historical perspective is necessary to understand the latent factors that accumulate slowly and then result in dramatic social collapse. Anthropology provides this perspective, and this chapter reviews insights concerning why some societies fail while others prosper.

“Quantitative Content” is presented by Laura Leets (3.3) and focuses on the central concepts underlying content analysis and how to conduct effective research. Content analysis is a technique for gathering and analyzing the content of text. Text can be anything written, visual or spoken, which serves as a medium for communication. Content analysis can be utilized in either qualitative or quantitative format; however, this submission focuses on the quantitative uses.

Joe Hewitt (3.4) contributes “The Peace and Conflict Instability Ledger Ranking States on Future Risks.” He presents country rankings from the 2010 Peace and Conflict Instability Ledger which are based on newly calculated risk estimates. The ledger represents a synthesis of some of the leading research on explaining and forecasting state instability. Hewitt also discusses some of the key results from the analysis, including the pivotal relationship between democratization and risk of instability.

Tom Rieger (3.5) provides a discussion into the problems related to developing stability models in “Perception is Reality: Stability through the Eyes of the Populace,” the largest problem being the limitations due to what sources are available. He describes how having a robust model of the level of stability in a given population based on perceptions of conditions would be a major contribution to the ability to plan for—and possibly help avoid—significant human suffering as a result of instability.

In “Assessing the stability of Interstate Relationships Using Game Theory,” Frank Zagare (3.6) explains the sense in which game models can be used to establish the stability, or lack thereof, of typical deterrence relationships and to understand the context of their policy recommendations. Game-theoretic models are a natural and intuitively satisfying framework in which to assess the stability of contentious inter-state relationships.

Robert Axelrod (3.7) presents a simple theoretical framework to enhance insight about partnerships for economic development. “Theoretical Foundations of Partnerships for Economic Development” clarifies the idea of theoretical foundations of partnerships by analyzing partnerships using game theory of an iterated prisoner’s dilemma. The analysis then reveals implications of selecting a partner, setting up a partnership, choosing a modus operandi, building trust, achieving selectivity, and performing monitoring and evaluation.

“Process Query System as a Framework for Modeling and Analysis of Regional Stability” is authored by George Cybenko and Douglas Madory (3.8). In response to similar problems across a variety of application domains, suggesting an underlying common analytic foundation, they propose two technologies—Process Query Systems (PQS) and Human Behavioral Modeling Language (HBML)—which could form the foundation for a standard, common computational capability. This capability could then be used to represent economic, health, political and environmental models related to regional stability, and reasoning about those models in the context of data, observations and other evidence.

The focus of Stephen M. Millett’s contribution (3.9), “The Use of Cross-Impact Analysis for Modeling, Simulation and Forecasting,” is to assert that cross-impact analysis may be just as effective, and arguably quicker, less expensive, and more robust, than systems dynamics. Millett asserts that it is a complementary approach that provides further foresight for the benefit of both forward-looking analysts and decision-makers, and he recommends further exploration as a supplementary approach to system dynamics, as well as other modeling, simulation and forecasting methods.

The Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance (3.10) submits “Development of a Framework for Action: Community Resiliency as a Means of Achieving Stability,” which outlines their process of creating a defining framework. The framework would determine what makes an individual household, community, and society resilient before, during, and after disasters.

Finally, Section Five looks at two case studies applicable to the Stability issue. First, Robert Popp (4.1) reports on the Sudan in “Sudan Strategic Assessment: A Case Study of Social Science Modeling.” This assessment was a strategic level proof-of-concept study in which a combination of quantitative and computational social science modeling and analysis approaches were developed and applied to better understand a complex “state” lacking true borders and encompassing many competing interests and complexities. Results demonstrated how multiple quantitative and computational social science models in conjunction with SMEs and other analyses are an effective, evolutionary step in the analyst toolkit, especially when the need is to provide additional lenses to look at highly complex and ambiguous stability problems (like the Sudan) to inform the decision-making process.

Second, Tom Mullen (4.2) presents “Analyzing Stability Challenges in Africa: A Case Study.” He notes that, with resources spread thin, we need better ways to rapidly understand what matters in each new situation, and to better understand why particular actions worked (and others did not), to aid in determining where and how those lessons might be more likely to work well. Assessment of highly complex situations quickly improves the ability to take rapid, effective action. Mullen’s case study attempts to provide lessons drawn from analyzing a number of stability situations on the continent of Africa over the past three years, with a focus on lessons in analyzing complex stability situations rather than specific actions to apply in a wide range of situations.

Contributing Authors

Hriar Cabayan (OSD), Barbara Sotirin (USACE-HQ, CERD), Robert Davis (ERDC-NH), Robert Popp (NSI), Andy Reynolds (U.S. Dept. of State), Anne Ralte (USAID), Herm Myers (OUSDP), Phil Kearley (JFCOM), Robert Allen (TRADOC), Lynda Jaques (PACOM), Sharon Halls (AFRICOM), Carl Dodd (STRATCOM/ GISC), Martin Drake (CENTCOM), MAJ Bradley Hilton (EUCOM), Tom Rieger (Gallup), Tom Mullen, (PA), Peter Steen (JS/J-5), Larry Kuznar (NSI), Clare Lockhart (State Effectiveness Institute), Philip Martin (UC-Davis), Jack A. Goldstone (GMU), Elizabeth Leahy Madsen (PAI), David L. Richards (Memphis), Ronald Gelleny (Akron), Peter Steen (JS/J-5), Jerome Delli Priscoli (USACE), J. Rolf Olsen (USACE), Kathleen D. White (USACE), Julie E. Kiang (USGS), D. Phil Turnipseed (USGS), Levi D. Brekke (Reclamation), David A. Raff (Reclamation), Roger S. Pulwarty (NOAA), Robert Webb (NOAA), Alex O.Dehgan (DOS), Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (USACE), James Diaz (LSU), Kenneth S. Yalowitz (Dartmouth), Ross A. Virginia (Dartmouth), Richard J. Stoll (Rice), Douglas J. Arent (NREL), Jeffrey Steiner (USDA), Timothy Griffin (Tufts), Donald Suarez (USDA), Debarati Guha-Sapir(CRED), Daniel Strickman (USDA), Victor Asal (Albany), Stephen Shellman(William and Mary), Lawrence A. Kuznar (NSI), Laura Leets (NSI), J. Joseph Hewitt (CIDCM), Tom Rieger (Gallup), Frank C. Zagare (SUNY Buffalo), Robert Axelrod (Michigan), George Cybenko (Dartmouth), Douglas Madory (Dartmouth), Stephen M. Millett (Futuring Assoc), Ame Stormer (DMHA), Jessica Wambach (DMHA), and Lt Gen (Ret) John F. Goodman (DMHA), Robert Popp(NSI), Tom Mullen (PA)

SMA PAKAF Rich Contextual Understanding (RCU) Project: Information and Analyses in Support of COIN Operations Executive Summary.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

The Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program provides planning support to COCOMs and warfighters. The program coordinates with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, and STRATCOM to support global mission analysis and to develop new analytic capabilities in support of specific tasking. These analytic capabilities seek to orient the commander to a decision for action. SMA develops multi-disciplined, multi-organizational teams for specific projects. It emphasizes the integration of human, social, cultural, behavioral, and physical sciences factors through participation of sociologists, anthropologists, economists, and physicist/engineers as well as universities, non-governmental organizations, and various interagency partners. SMA efforts produce focused, multi-disciplined strategic and technical assessments as well as documentation, training and education in the application of newly developed analytic tools.</p>,

The RCU Challenge

In August 2009, COMISAF asked the SMA program to help provide a “rich contextual understanding” of the Afghan political and social environments to facilitate the conduct of ISAF’s revised COIN mission. The SMA effort initiated a pilot effort for rapidly developing a rich understanding of the interrelations of social, economic, political with security factors down to the district level in Afghanistan.

RCU Products

The RCU effort produced multiple Afghanistan and Pakistan-related products focused on 16 districts of interest in Afghanistan and 10 in Pakistan. Specifically, products include:

- an extensive SharePoint Data Library of DoD, other USG, academic, and international data and analyses relevant to the PAKAF AOR;

- a broad range of district and province-level multi-method qualitative and quantitative models and analyses based on polling and interview data generated specifically for the project;

- proceedings of inter-agency project workshops (e.g., Helmond Province Deep Dive, Assessment Metrics);

- integrated response to specific operational questions posed by ISAF HG;

- reach-back support and methodological input to IJC District Assessment metrics development; and

- a conceptual model to guide data collection and fusion as well as to support decision making relative to ISAF efforts to promote governing, economic and social stability in Afghanistan (i.e., the Political Durability Model)

Operational Findings

The PAKAF RCU effort resulted in many operational findings but two key general ones. First, at present, tactical/battlefield analysis and assessment cannot be done from CONUS. Not only are the analysts too far from data which can, despite recent advances, still take weeks to months to access, but, as established in Afghanistan, SOICs and other in-theater analysis cells are better suited to work within AOR battle rhythms. In contrast, CONUS-based analyses can add the most value on longer-term strategic and contextual issues and as reach-back support. The second general finding is that also despite advances, the availability of systematically collected and reported data remains a critical need--both for analysts working in-theater and CONUS. Without properly collected and documented data, we lose the ability to accurately assess and learn from the environment.

Interagency, Academic, and Industry Participation

The RCU effort involved broad participation from across the Department of Defense (i.e., Services, CENTCOM, SOCOM IATF, JIEDDO, STRATCOM, etc.), interagency partners (DEA, DNI, DOC, DOJ, DOS, Treasury, USAID), Allies (Australia MOD, UK Foreign Office), academics (Boston U., GMU, Harvard; U of Nebraska, Omaha, Penn, U Alabama, Dartmouth, SUNY, NPS, Texas A&M), and industry.

The academics not only challenged conventional thinking, they inserted rigor and fresh thinking into the effort. By reaching out to the academic community, the RCU team strengthened the oftentimes uncertain relationship between the USG and academia.

Conclusion

The SMA RCU effort piloted a process for creating a rich understanding of the context and social and political environments in a large and unfamiliar area of operations that might serve as a template for other COCOMs as they seek to gain insight into the human, social, and cultural terrains of their own operating areas.

Proceedings from the Neurobiology of Political Violence: New Tools, New Insights Workshop.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

The Neurobiology of Political Violence: New Tools, New Techniques workshop hosted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), United States Strategic Command (STRATCOM), the Joint Staff, and the Strategic Multilayer Assessment Office (OSD) brought together nearly 80 representatives of government, academia, and industry in Bethesda, MD from 1-2 December 2010. The workshop facilitated a broad discussion of the current state of the art within the related fields of neuroscience, neurobiology, and social psychology as it relates to deterring political violence. While most panelists emphasized the prematurity of applying current research to real world problems within the national security and homeland defense space, they all agreed that the tools of neuroscience and related fields would serve to better inform current deterrence and messaging strategies.

The workshop was organized as a series of panel discussions and individual discussion sessions. This executive summary is organized by session for ease of reading and use.

Opening Remarks

Ms. Abigail Chapman, Senior Research Scientist at NSI, welcomed the workshop participants to the Neurobiology of Political Violence workshop with a discussion on the design and intent of the workshop. She noted that researchers have always been fascinated by the complexities of the human brain and, in particular, investigating the relationship between mind and body. In order to develop a deeper understanding of individuals who are involved in violent extremist activities, it is essential to use a multi-method, multi-disciplinary approach that specifically focuses on the complex relationships between attitude and intent formation and, ultimately, behavior manifestation. Thus, panelists were purposely selected from diverse disciplines and backgrounds.

Although the conference is entitled, The Neurobiology of Political Violence: New Tools, New Insights, the Steering Committee sought to encourage open discussion of pertinent findings and to allow for the cross-pollination of ideas, identification of areas for collaboration, and topics upon which other findings can inform and augment the dialogue. Additionally, she sought to emphasize that the conference served as an invaluable launching point for previously unknown research and proliferation of ideas and concepts beyond their initially intended audience.

Introductory Briefings

Ms. Abigail Chapman moderated the first session, which focused on highlighting the connection between basic research and the topics of counter-terrorism, radicalization, violent extremism, and deterrence. The briefers set the stage for the workshop with a discussion of the historical and potential future application of research findings from the fields of neurobiology, social psychology, and linguistics to further our understanding of political violence. This first session (taken together with the read-ahead material) provided conference participants with sufficient background to not only understand the subsequent research presented, but also turn a critical eye towards understanding the potential implications and limitations of this area of research.

Panel Discussion: Basics of the Science

The first panel discussion on the basics of science was moderated by LtCol William Casebeer, DARPA, with a specific focus on understanding behavior and attitude formation from the disciplines of social psychology, cognitive neuroscience, and political science. The panelists spoke on a variety of related topics, yet all agreed that it is critical to have a common set of definitions when discussing violence across disciplines to ensure that the same concept is being addressed. Although the field of neuroscience is exciting, it is essential for people to understand that the research is at a relatively nascent stage with some topical areas more developed than others.

Panel Discussion: Research I

The first research panel focused on a discussion on the psychological and neurobiological mechanisms underlying violent behavior and decision-making processes. The research panel discussion was moderated by Dr. Tom Feucht, a science advisor to the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) at the US Department of Justice (DOJ). Panelists discussed the ways in which research findings from the fields of social psychology and neuroscience can inform and enrich our understanding of how political attitudes are formed and how and when people practice deception. Additionally, panelists discussed the various ways in which researchers are able to use advanced technologies, such as simulated environments and functional magnetic resonance imaging, to understand how decisions are made and, more specifically, what components of a message are the most persuasive and “sticky” to a target audience. This discussion culminated in the agreement that further research is required in this area, but that there is great benefit to be gained from pairing research targeted at understanding attitude formation and decision-making processes with the tools employed by neuroscientists and neurobiologists.

Panel Discussion: Research II

The second research panel focused on aggression, fear, and trust with a specific emphasis on fear’s impact on decision making and violent behavior. The panel was moderated by Dr. Amber Story of the National Science Foundation. The panelists discussed several topics, including the psychologically motivating factors of terrorism inherent in the Terror Management Theory--a theory that is founded upon the basic principle that human beings are motivated to adopt and police a cultural belief system in order to allay their concerns over their own mortality. Sets of sacred values underpin strong belief systems; such values include those beliefs that an individual is unlikely to barter away or trade no matter how enticing the offer is. While further research is required, sacred values may prove a pathway towards better understanding the deep underlying motivations behind certain acts of political violence and identifying values that are less resistant to change such that they may be used to alter an individual’s belief system and/or motivational schema. The panel also discussed the interactive effect of the environment, developmental process, and genetic expression reflected in the brain. Additionally, the panel discussed the advancement of science in regards to exploring the association between genes and the outward manifestation of behaviors relevant to actions of political violence.

Panel Discussion: Research III

The final panel, moderated by Dr. Debra Babcock, NIH, explored research regarding the impact of emotions and stress on decision making and decisions to engage in violent behavior. Several panelists discussed the ways in which emotion or emotional responses to negatively-perceived stimuli interact with an individual’s decision-making process, attitude formation, and subsequent behavior. Emotion plays a significant role in an individual’s decision to engage in violent behavior; for instance, it was mentioned that violence is an emotional act between groups that can be influenced through genetics, environment, narratives, and perceived behaviors of others.

Building upon the notion that emotions can be modified and transformed through stories or narratives, it may be possible that once the right trigger mechanisms within a story are identified and altered, emotion, or at least the cognitive or behavioral manifestation of the emotion, may prove to be malleable. Additionally, several panelists noted that it may be possible to identify situations in which actions of political violence are likely to occur through observing identified tendencies. For example, a historical examination of state communications preceding international acts of violence show a diminished amount of cognitive complexity in the time immediately prior to the action of the aggressor, but not for the attacked. It was hypothesized that this occurs because the aggressor has already committed to a decision, is no longer stressed or anxious about the outcome, and is engaging in heuristic (vs. systematic) processing of information. Thus, by studying the cognitive complexity of a state leader’s communication, it may be possible to identify times in which they are seemingly engaging in heuristic processing of information and, thus, more likely to already have a set course of action in mind. Additionally, other research has shown that there may be universal facial expressions for the identified emotions of contempt and disgust that are generally displayed on the faces of individuals immediately prior to engaging in acts of violence. If future research builds upon the findings, then this may prove to be useful research for identifying critical intervention moments.

Putting It All Together--What Does This All Mean?