SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Cooperation Under the Shadow of the Future: Explaining Low Levels of Afghan Cooperation with ISAF Development and Security Projects

Author | Editor: Geva, N. & Bragg, B. (NSI, Inc).

This project addresses two major interrelated objectives. The first objective is a substantive one: we are interested in better understanding why Afghan participation in ISAF and ISAF-sponsored initiatives is low, even when participation offers the opportunity for significant near-term benefits. We contend that the ISAF mission in Afghanistan presents a clear example of a shadow of the future decision problem for the Afghan people. Specifically, that low levels of Afghan participation result from the knowledge that ISAF presence is finite and that, after ISAF withdraws, insurgents will punish those who cooperated effectively negating the value of any benefits gained from that cooperation. This situation presents a serious policy challenge for ISAF, and a better understanding of the dynamics and factors that affect Afghans collaboration with ISAF’s local initiatives will help develop policies that can mitigate the current situation.

The second, broader, objective is to demonstrate the utility of the experimental method to the work being conducted by SMA and other groups supporting US forces in complex environments such as Afghanistan. That is, we posit that experimentation can help us understand (test hypotheses and provide empirical evidence) complex contexts where data are scarce and the data that is available are problematic.

The utility of the experimental method is tested in the context of the substantive question of this project: Why are Afghan citizens reluctant to cooperate with small-scale initiatives started by ISAF forces? Their intention is to improve conditions for the Afghan people as well provide incentives to support the consolidation of an Afghan governed nation. While there are several potential accounts of why the Afghans do not collaborate with ISAF – mostly cultural – in this paper we explore the utility calculations of the Afghans. We focus mainly on the Afghan perception of the major counter force to prevent such collaboration, that is, the Taliban. In their attempt to stop such cooperation the Taliban conducts nightly deterrent acts, which include addressing threatening letters to the locals and sabotage for those collaborating with the American forces. We argue that in addition to these small-scale Taliban attacks – there is another dark cloud hovering in the future. The fact that The ISAF’s commitment is finite and the related issue of the future relative strength of the Taliban versus the ISAF established Afghan government.

This study presents a conceptual model designed to help explain why Afghan citizens are reluctant to cooperate with ISAF projects intended to improve their quality of life in the near-term. Rather than rely on cultural or historical explanations for this reluctance we propose that this behavior is consistent with rational calculation that gives weight to future costs as well as near-term benefits. It is this shadow of the future that undercuts the perceived benefits to cooperation and decreases individuals’ willingness to cooperate with ISAF projects.

Although preliminary these findings suggest several important factors that need to be taken into consideration when determining the likely response to ISAF projects.

- The shadow of the future matters: The perception that GIRoA will not emerge as the stronger actor once ISAF leaves is critical in preventing cooperation with ISAF projects in the present

- These results suggest that not all subjects are utility maximizers, rather decisions are based on the principle of minimizing potential losses. This is most clearly demonstrated by the choice to pay off Taliban or sit on fence

- Choice can in some instances be better understood as driven by minimizing risk, rather than by the potential for gain.

These findings support the current ISAF focus on strengthening GIRoA’s governing capacity. If Afghans develop greater trust in the strength of GIRoA; its capacity to provide basic governance functions such as security and rule of law; then the impact of the shadow of the future will begin to decrease. As concern over future reprisals diminishes, cooperation with ISAF projects can be expected to increase. As increased cooperation and investment in ISAF projects indirectly reinforces the governance capabilities of GIRoA over time a positive feedback loop should develop.

Analysis of Discourse Accent and Discursive Practices Indicators & Warnings Practices I&W.

Author | Editor: Toman, P., Kuznar, L., Baker, T. & Hartman, A. (NSI, Inc).

Because 1) discourse is not neutral, and 2) people differentiate between in-groups and out- groups, discourse almost always reflects an individual’s in-group and out-group assumptions. Boundary maintenance between groups that are “good” or “like us” (in-groups) and those that are “unlike us” or “bad” (out-groups) forms a significant – albeit often subconscious – part of discourse. This is true for all languages and societies, including both English- and Arabic- speaking.

This project was initiated at the request of behavior influence analysts at the National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC). NASIC had found the distinction between “in-groups” and “out-groups” useful for their analyses. This effort was initiated to explore this phenomenon further, to assess how in-groups and out-groups are indexed and constructed in texts. Specifically, the goal was to develop a systematic methodology for identifying and interpreting in-group/out-group discursive practices in Arabic. The intent was to solidify an approach that could focus analysts’ attention on issues of in/out group dynamics, as well as be reproducible and trainable.

The research effort proceeded in two phases. Phase I was dedicated to covering the academic literature on discourse analysis and the initial construction of a codebook. The codebook contains a catalogue of linguistic devices used to express in/out group sentiments in Arabic. Phase II was focused on expanding that codebook and integrating insights from linguistically trained Arabic speakers and Arabic speakers with a more colloquial understanding of how in/out group sentiments are expressed; that is, to create a methodology that was natural and did not require formal training or expertise in critical discourse analysis. In addition, a proof-of-concept was conducted of an existing methodology for tracking relations between people and groups, called cognitive or integrative complexity analysis. Cognitive complexity analysis refers to a specific methodology developed in the field of political psychology that is used on the discourse of political elites. It does not provide sentiment analysis, but it does provide indicators of when one group is likely to act violently toward another group. Finally, a survey of alternative methods to consider for future work was completed.

Before developing a methodology/codebook, a literature search (Appendix A) was conducted encompassing social psychology, the history of discourse analysis and other social science literature related to narratives and discourse (e.g., political science related literature on cognitive complexity and integrative complexity). The literature search identified discursive mechanisms related to in-group/out-group. In-group alliance and out-group distancing are reflected linguistically through numerous discourse phenomena. As determined by the review of academic discourse analytic literature and analyzing Arabic newspaper discourse, the most significant techniques that establish in-groups and out-groups in third-person Arabic newspaper analytic prose include:

- Lexicalization (word choice)

- Quotations

- References

- Allusion

Monitoring linguistic phenomena, with attention to these four in particular, can help identify and track alliances and tensions between groups over time. Focusing on these in-group/out-group related discursive mechanisms, a case study was conducted with Arabic documents provided by NASIC to identify the ways in which these discursive mechanisms manifest in Arabic discourse. The result of this was a critical discourse analysis based Methodological Primer for in-group/out- group discourse in Arabic (Appendix C).

In order to validate the extensibility and robustness of this methodology, a subsequent study with more Arabic speakers and more Arabic documents was conducted. This second study resulted in a new methodology (Appendix F) which did not require any training in critical discourse analysis. In developing this second approach, there was the progression from the insights of a single academically trained analyst, to focus groups of academically trained analysts, to a larger body of colloquial readers. The resulting codebook incorporated the insights of both expert linguists and ordinary speakers through the application of grounded theory. From coding Arabic speakers’ analyses during the final phase of the project, a series of ten “factors” was identified along which Arabic speakers assess in/out group alignments in Arabic documents. These factors cue the reader or analyst to understand a particular group as a member of the author’s in-group or a member of the author’s out-group. One of the conclusions of this second study, among other quantitative findings, was that although analyst language level affects which of these factors are noted, there is no statistically significant difference between (self-rated) native speakers of Arabic and near-native speakers in identifying the in-group/out-group factors.

In addition, a proof-of –concept of the cognitive complexity/integrative complexity assessment method was explored. The notion is that this could provide another method to assist an analyst in interpreting discourse. Cognitive complexity measures a subject’s psychological complexity as represented by their public statements and writings, which can be used as an indicator and warning of impending hostilities. Integrative complexity measures the ability of an individual to see multiple perspectives of an issue or situation and integrate those viewpoints or perspectives. Higher integrative complexity has been correlated with cooperative behavior.

The critical event used for the proof of concept of integrative complexity assessment was the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri on February 14, 2005. In particular, the statements of Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad in the interval immediately before and after the Hariri assassination in 2005 were used to assess whether changes in integrative complexity, as suggested by the literature, could serve as an instructive analytical tool in the run up to serious international events. This is a particularly useful case study because of Al-Assad’s denial of Syria’s involvement in the assassination and the international community’s contradictory conclusion that there was some level of Syrian involvement (based upon the Mehlis investigation). Based upon this Al-Assad case study, National Security Innovations, Inc. (NSI) found a statistically significant (p-value=.01) difference between the period immediately prior to the assassination of Rafic Hariri (October 2004 thru January 2005) and both Al-Assad’s baseline (October 2003 thru May 2004) or the period following the assassination (February 2005 thru December 2005). This confirms the general research findings in the political psychology literature.

In summary, the following was accomplished:

- Literature search of discourse analysis with a view to applying it to identifying, understanding and interpreting in-group/out-group discourse

- Initial case study of critical discourse analysis methodology for identifying in-group/out- group discursive mechanisms in Arabic and development of primer

- Subsequent case study of Arabic in-group/out-group discourse which identified key rhetorical phenomena and intensifiers

- Development of a phased method for using analysts with different levels of training to produce codebooks

- Method made use of manually and automatically retrieved web documents

- Method progressed from a single academically trained analyst, to focus groups of academically trained analysts to a larger body of colloquial readers, enabling the construction of a code book that incorporated both expert linguistic and more common views

- Discovered 10 factors by which Arabic speakers assess in/out group alignments in Arabic news documents, and 13 factors by which Arabic speakers assess intensification of sentiment

- Proof –of-concept of integrative complexity, as developed by Suedfeld and Tetlock, demonstrated the potential to provide indicators and warnings of possible changes in threat posturing through the analysis of leader’s and political elites’ public statements; Bashar Al-Assad’s cognitive complexity shifted as predicted by the literature, with his cognitive complexity decreasing in the period prior to the assassination of Hariri and returning to baseline in the aftermath

- Application and adoption of grounded theory to coordinated analysis

- Exploration of the effect of analyst language skill and linguistic training on coding

Future work will likely employ the discourse methodology and the cognitive complexity methodology in tandem to provide independent streams of evidence concerning how groups are aligned with one another. In addition, some recommendations are made of other potential methods (e.g., narrative analysis, ethnographic approaches) that may be useful for tracking intergroup relations through their discourse.

Defining a Strategic Campaign for Working with Partners to Counter and Delegitimize Violent Extremism Workshop.

Author | Editor: Arana, A., Baker, T. & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Dr. Hriar Cabayan, OSD, welcomed the participants on behalf of the Department of Defense (DoD), the State Department (DoS), and the RAND Corporation to the Defining a Strategic Campaign for Working with Partners to Counter and Delegitimize Violent Extremism workshop held from 19-20 May 2010 at Gallup World Headquarters in Washington, DC. The workshop focused on strategic communications and violent extremism and was designed to inform decision makers and was not intended as a forum for policy discussion. The workshop emerged from an SMA- and AFRL-sponsored white paper entitled Protecting the Homeland from International and Domestic Terrorism for Counter-radicalization and Disengagement. As the white paper was being written, it came to Dr Cabayan’s attention that Dr. Paul Davis at the RAND Corporation was writing an integrative literature review on the subject. The RAND report was entitled Simple Models to Explore Deterrence and More General Influence in the War with Al-Qaeda. Building on that, CAPT Wayne Porter wrote a paper on the strategic campaign to counter and delegitimize violent extremism, which resulted in the genesis of this workshop.

The workshop was organized as a series of panel discussions and individual discussion sessions. This executive summary is organized by session for ease of reading and use.

Opening Remarks: Pradeep Ramamurthy

Pradeep Ramamurthy, Senior Director for Global Engagement on the White House's National Security Council (NSC), began the conference with a discussion of how the current Administration defines countering violent extremisms (CVE) and strategic communications. He then provided an overview of key communication and engagement goals and objectives, highlighting that CVE was one of the Administration's many priorities. Mr. Ramamurthy then provided an outline of critical elements of strategic communications that should stay in participants' minds for the duration of the conference; noting (1) the importance of coordinating words and actions that involves an all-of- government approach; (2) the need to do a better job of coordinating multiple messaging efforts across agencies; and, (3) listening and engaging with target communities on topics of mutual interest, not just terrorism. He sought to emphasize that the conference served as an invaluable launching point for government introspection and the injection of new ideas from outside experts.

Session 1: Trajectories of Terrorism

Dr. Laurie Fenstermacher, AFRL, and Dr. Paul Davis, RAND Corporation, moderated the first session of the day on the causes and trajectories of terrorism from perceived socio-economic and political grievances to recruitment and mobilization. The participants, who included representatives from government, industry, and academia, spoke on a variety of related issues including the dynamics and tactics of violent non-state actor (VNSA) communications and decision-making, the role and importance of ideology, and the key causes of popular support for terrorism and insurgencies. The panelists reinforced the need for tailored strategies for individuals based on their motivation (e.g., ideology, self-interest, fear) or based on other factors (e.g., Type 1 or 2 radicals, fence sitters)such as the need to focus on “pull” factors (recruiting, compelling narratives/messages) versus “push” factors and the need to understand ideology and associated terms. Also asserted was the need to target strategies towards the function of ideology (e.g., naturalization, obscuration, universalization and structuring) with culturally and generationally sensitive strategies, which are not based on inappropriate generalizations of past strategies, groups, or movements. Finally, the panel stated that some models need to be changed if they are to be truly useful in understanding terrorism (e.g., rational actor models may need to include altruism). This first panel (taken together with the reference materials) provided a snapshot of the current understanding of terrorism from the perspective of social science. As the first session of the conference, the panel discussion served to provide a common understanding and foundation for the remainder of the workshop.

Working Lunch: An All-of-Government Approach to Countering Violent Extremism: The Value of Interagency Planning

Two representatives of the National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC) and another representative of the USG outlined the key components of an All-of-Government approach to countering extremism. The NCTC coordinates the efforts of various agencies like the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI on issues of counterterrorism; consequently, they have significant experience in the domestic context. The critical element of the NCTC approach is the importance of “going local” or structuring interventions and responses within the context of a given community, thereby recognizing the inherently local nature of the radicalization process. The NCTC representatives noted the critical importance of getting outside the Beltway and implementing micro-strategies. An unattributed speaker then spoke about the importance of understanding the language that the United States uses to deal with violent extremists and the danger of using the language and the narrative of violent extremism because it only perpetuates their message to the rest of the world. The USG needs to do a better job of communicating its objectives and working with communities to develop solutions to deal with extremist violence. Partnerships with communities have been important tools in helping to address issues of violence, such as gangs, and can be a valuable resource to address the issue of extremist violence. Ensuring that US actions and words are synchronized, and not in contradiction to each other, is critical. As a federal government, the United States must work hard to better understand the complexity of extremist violence by working with state and local authorities, academics, and communities

Session 2: Whether Violent Islamists Groups Can, in Fact, be Delegitimized?

The panelists of Session 2 were somewhat divided on whether delegitimizing extremists should be approached from a religious perspective or if efforts should be focused on eliminating or minimizing contributing factors. Some participants emphasized the importance of making use of the religious jargon and institutions (like Fatwas) to marginalize the leaders and participants in violent extremists in the eyes of their broader religious communities; indeed, one panelist recommended changing the underlying Quranic hermeneutics to recognize the historical nature of the Quran. Other panelists were wary of labeling extremism as a religious problem, because radicalization and extremism are not new developments in the Middle East; it existed during the nationalist campaigns of the 1960s much as it does today. Almost universally, panelists acknowledged that the West needs to do a better job of selling its own message of what it is that it stands for and what it tries to do in the international community.

Session 3: Strategic Campaign to Diminish Radical Islamist Threats

Session 3, moderated by CAPT Wayne Porter and Special Representative to Muslim Communities Farah Pandith, focused on several features of an effective campaign to combat radicalization. However, there was major contention regarding the degree to which the United States should focus on its own views and reputation versus focusing on supporting other groups or focusing on strategic communication in terms of other countries. Nonetheless, the session reached consensus on several major points including supporting historical traditions and customs of indigenous Muslim cultures and closing the say/do gap to increase consistency. This consistency will lead to credibility, which is critical in conjunction with whether the message is compelling and whether it connects with the audience. It was also considered important to align government, private sector, and Muslim leaders to forge strategic alliances. This empowerment of many voices creates competition for radicals attempting to monopolize communications to these populations and allows the United States to partner with and support potential leaders. Such an empowerment strategy also allows the United States to implement a wide variety of approaches and employ diagnostic measures to recalibrate over time. Ultimately, whether it is by telling the story of modernity, shining a light on outreach efforts, or just assisting those around the world who are countering extremists for their own reason, the approach must be sustainable and global in nature.

RADICALIZATION

Belarouci: The Genesis of Terrorism in Algeria

Dr. Latéfa Belarouci, a consultant, offered a historical overview of the development of fundamentalism and extremism in the Algerian context, noting that it was not a recent development, but instead grew out of the colonial experience. When the French colonized Algeria, they robbed the Arab populations of their identities, engaging in ethnic politics that equated the darker skinned, Arabic speaking Arabs as something different from the paler skinned Berbers and the French themselves. This destruction of collective identity and the subsequent marginalization of native politics created an environment fertile for Muslim extremism. After the accession to independence, the first constitution enshrined the special place of Islam and Arabic in the Algerian psyche and the 1994 amnesty gave terrorists reprieve, though not necessarily to their victims. Fundamentally, Dr. Belarouci’s presentation illustrated the importance of understanding the historical context when confronting terror and extremism.

Everington: From Afghanistan to Mexico

Alexis Everington of SCL made a presentation outlining recurrent themes relevant to radicalization that had arisen from projects SCL had conducted around the world. Key themes for consideration in strategic communications included: mobilizing fence sitters; identifying the correct target population; managing perceptions of common enemies; engaging in local infospheres effectively; controlling the event and the subsequent message; making use of credible messengers; and understanding the importance of perceived imbalance. Everington noted that these themes are shared but are important to different degrees. Strategic communication must acknowledge, understand, and use these themes and their levels of importance, in the fight against radicalization.

Frank Furedi: Radicalization and the Battle of Values

Dr. Furedi of the University of Kent, UK offered findings from his research and his experience as an observer of events in Europe. He concluded by attempting to refute six key myths including: that radicalization is predicated in an ideology; that radicalized individuals suffer from some psychological deficiency; that extremism is driven by poverty or discrimination; that the internet is a key mobilizer or cause of extremism; that oppressive acts abroad (i.e., Israel and Palestine) motivates extremism; and finally, the notion that extremism is directly related to Islam.

Sageman: The Turn to Political Violence

Dr. Sageman of the Foreign Policy Research Institute elaborated upon his view of the transition process to radicalization and then extremism. He detailed the stages of engagement with radicalism from disenchantment and the development of a sense of community with counter-cultural forces to further involvement and sometimes violent extremism. He noted that it was very rare for someone to be caught up in a counter-cultural milieu and then end up undertaking terrorist actions; however, he noted that much of this transition occurs at a very local, micro level - not through the internet or other media.

Casebeer: Stories, Identities and Conflict

Dr. (LtCol.)Casebeer’s presentation illustrated the power of narratives to motivate action and to provide an internally resonant message and rationale for action. He detailed the common structure of narratives and how they engage cognitive structures and impact reasoning, critical thinking, and morality. Fundamentally, he concluded that stories help mediate the divide between the initial stimulus to act and the ultimate action, if it ever reaches that point.

INFLUENCE/DETERRENCE

Trethewey: Identifying Terrorist Narrative and Counter-Narratives

Dr. Trethewey of Arizona State University offered a background on narratives throughout history and their uses in today’s context. In terms of the narratives themselves, and why they are critical to understand, humans have acted as narrators throughout history. Historically narratives have helped to answer three questions:

- How do people connect new information to existing knowledge?

- How do people justify the resulting actions we take?

- How do people make sense of everyday life?

Understanding narratives provides a shorthand introduction into cultural comprehension. The critical components of narrative systems are stories, story form, archetypes, and master narratives. Narratives do not provide a full history or full understanding, but perhaps they provide a shorthand understanding that can prevent or reduce the possibility of making strategic communication gaffes. Additionally, it may suggest something about how to amplify the voices that are doing some interesting narrative work. However, it was agreed upon that the United States needs to be careful in invoking narratives of ridicule, but explore how those narratives work in contested populations. Ultimately, the environment has a lot to do with how a radical message resonates with a population. The master narrative then is always grounded in cultural, social, historical, and religious assumptions and radical extremists take up and appropriate those narratives for their own ends. The role of the US government should be to better understand those narrative strategies and work toward more effective, equally-culturally grounded counter narratives.

Gupta: Mega Trends of Terror: Explaining the Path of Global Spread of Ideas

Dr. Gupta of San Diego State University presented the reasons why messages spread within societies. He began with the messengers, arguing that there are three main actors who are present and extraordinarily important to the spread of ideas. The first actor is the connector. The connectors are the social networkers with connections to many people and with the necessary social skills to connect people to other people or ideas. Then there is the maven or “the accumulator of knowledge.” This actor is a theoretician. The third critical actor is the salesman. Dr. Gupta noted that these individuals are present in many of the social and religious movements around the world. He then concluded that the environment or context must be ripe. Lastly, the message itself must stick to the receivers, or those who are necessary to support a movement. Dr. Gupta discussed three factors that cause a message to stick: simplicity, a compelling storyline, and the idea of impending doom should the audience not act. Ultimately, any individual within an audience who is captivated by the message will seek out the opportunity.

DERADICALIZATION AND COUNTER-RADICALIZATION

Horgan: Assessing the Effectiveness of Deradicalization Programs

Dr. Horgan of Penn State University emphasized the importance of distinguishing between deradicalization and disengagement in terms of violent extremists. In his research, Dr. Horgan has interviewed over 100 respondents—only one had said that he had no other choice but to join a radical group. He outlined key push factors for disengagement including disillusionment with the goals of the group and the group’s leadership. He also outlined the key objectives of deradicalization programs while highlighting the problems faced by deradicalization programs in Saudi Arabia.

Hamid: A Strategic Plan to Defeat Radical Islam

Dr. Hamid of the Potomac Institute emphasized the importance of confronting radicalization on its own territory using the metaphor of disease - not only must one treat the symptoms of the disease (terrorism), but one also has to treat the disease itself (the radical ideology). His key recommendations were related to preventing the formation of passive terrorists (on the fence) and interrupting the transition of the latter to active ones. These recommendations included making use of Fatwas denouncing terrorism; exploiting rumors to denigrate the heroic image of radicals; and instilling a sense of defeat in the mind of the radicals. Fundamentally, he emphasized the importance of understanding the underlying cultural paradigms that underpin these social movements. Additionally, based upon his personal experiences with and observations of radical Islamic groups over the last 25 years, he considered radical religious ideology to be the most crucial component of both the development of radicalization and any successful interventions against it.

Phares: Muslim Democrats

Dr. Phares, National Defense University, argued that there was irrefutable evidence that extremists were motivated by a similar and comprehensible ideology—that of global jihadism with two main threads: Salafism and Khomenism. Despite this jihadist underpinning, observers, and others in the West must be careful to distinguish between the three main threads of jihadism in usage: Jihad in theology, in history, and in modern times, which represents the current movement.

Davis: Day Two Wrap Up

Dr. Paul Davis of the RAND Corporation synthesized many of the ideas that had been discussed over the two-day workshop. He noted that throughout the workshop there had been consensus as well as debate. One of the points that participants have agreed upon is that it is folly to speak about “terrorists” as a monolith. It is critical to take a systems perspective where the individual components are differentiated, providing a number of leverage points for counterterrorism. Another striking debate that has taken place over the two-day workshop involved the relative emphasis that should be placed on the ideological end or religious aspects of the problem. Those who take the broadest view see the troubles the world is going through as another wave that will resolve itself in its own time. However, that sanguine view assumes that countervailing forces will eventually succeed. Conference participants are part of such countervailing forces. Dr. Davis also highlighted discussion over whether the United States should focus on its own values and stories or on focusing strategic messages about critical issues such as interpretations of Islam. Most conference attendees, he said, were skeptical about the latter. He also discussed lessons learned from the Cold War about the value of truthfulness and credibility in strategic communications, as distinct from baser forms of propaganda. Overall, Dr. Davis pointed out that many of the points that appeared to be in conflict at the conference are not necessarily so when it is realized that the United States can maintain one focus at the strategic level and allow those who are closer to the action to focus on the tactical, contextual, level.

Selected Chapters:

- Sudan Strategic Assessment: A Case Study of Social Science Modeling (R. Popp)

- Trajectories of Terrorism (T. Rieger)

The Use of Remote Sensing to Support the Assessment of Political Durability.

Author | Editor: Canna, S., Baker, T. & Yager, M. (NSI, Inc).

The Use of Remote Sensing to Support the Assessment of Political Durability Pilot Workshop was held jointly by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Office and the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC) from 7-8 December 2010 in Arlington, Virginia. The workshop is part of a proposed effort called Observable Manifestations of Hearts & Minds: Identifying Opportunities for Remotely Sensing Popular Perceptions Effort.

The goal of the proposed project is to develop regionally tailored, global remote sensing1 collection requirements and strategies in order to identify the sources of fragility and, potentially, early action when fragile states show vulnerability. The first step is to take a deep dive into the use of remote sensing technologies to assist social science assessments in the areas of governance, security, and development.

Environmental conditions manifest constraints and enablers on human activities, community resilience, and regional situations. At the same time, humans exert influence on the environment, which reflect changes in agriculture, development and, indirectly, population-based characteristics, behaviors, and trends. This conceptual bridge points to the potential that one can use remote sensing as proxies or compliments for political, social, military, economic, and other variables of concern to the evaluation of stability and resilience. Accordingly, measurable environmental change exhibited on the Earth surface may provide an important, though indirect, indication of state stability or potential conflict, acting in combination with other social-economic and institutional factors.

Over the past decade, several major research efforts link natural sciences through the study of land- use and land-cover change with the social sciences. However, many of the efforts result in models generally too complex for non-researchers. We urgently need to adapt and accelerate the convergence of social and physical data into a coherent implementation strategy, which, for example, the US Government can use today in the Counterinsurgency (COIN) environment and which can also extend globally to provide more robust indication of stability indices in areas of national concern. In a COIN environment, the potential role of remote sensing becomes very important due to the cost and risk associated with gathering information and making assessments using deployed forces.

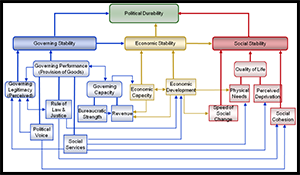

In Afghanistan, transition decisions by the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) involve identification of “stable” governing and economic systems, as well as resilience of that (stable) condition. We define political durability as a function of governing, economic, and social stability. In this case, why do we think that “durability” rather than just stability has critical importance? A system that proves stable under a given set of conditions can nevertheless contain latent drivers of instability, which emerge once conditions become different. Transition from ISAF to local leadership in Afghanistan represents such a change in conditions.

For determining when a political system has stability and resiliency sufficient for self-sustainment in the face of internal and external shocks, we can use a conceptual framework called a Durability Model. For Afghanistan, the Durability Model aims to support ISAF transition decisions by providing decision makers with a theoretically rigorous, yet intuitively reasonable, framework for understanding the complex Afghan environment. Indicators lead to derived operationalized variables and to suggestions for data requirements and collection methods, (e.g., social services-- water measured as an observable plus a survey item). The degree to which remotely-measured environmental indicators can support a durability framework remains unexplored.

The workshop had a two-fold objective:

- to provide a pilot forum to discover, explore, and develop the nexus between remotely- sensed environmental indicators and population-based metrics using the situation in Afghanistan as a use case; and

- to set the scope, terms, and charter for subsequent efforts across the DoD, inter-agency community, and the science academies to learn and discuss the potential of remotely- sensed physical/environmental data in a surrogacy or complimentary role for operational metrics in stability operations (tactical) and/or in a role as a long-term indicator of political durability (strategic).

On the first day, participants shared their expertise in remote sensing technologies, operational objectives and metrics, social and cultural data from the Pakistan and Afghanistan Rich Contextual Understanding (PAKAF RCU) Study, causes of state failure, and related agency initiatives and research. By the end of the first day, items of interest for further recommendation to ISAF were identified for development.

On the second day, participants broadened the discussion to explore the feature space of situations not particular to the Afghanistan case study. Participants examined similarities and dissimilarities between the case study and the wider global situation. In the afternoon, participants developed the concept and charter for a second workshop in early spring 2011 to take some of the salient generalities and specific recommendations from this effort to a broader dialogue.

Understanding the spectrum of remote sensing opportunities in the context of population-based frameworks constitutes the long-term goal. The effort also seeks to develop regionally tailored, global remote sensing collection requirements and strategies in order to identify the sources of fragility and early action when fragile states show vulnerability. Accordingly, the learning, outcome, and recommendations from this pilot event will lead to a more broad-based workshop early in 2011 and associated white paper.

Subjective Decision Analysis Final Report: Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Russia, Saudi Arabia & Syria.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A., Canna, S., Chapman, A., Hartman, A., & Polansky (Pagano), S. (NSI, Inc).

The SMA Strategic Deterrence effort is a methodological study to evaluate the appropriateness and utility of modeling and wargaming to support the analytic requirements of the Deterrence Operations Joint Operating Concept (DO JOC). The objective of the study is to determine which aspects of deterrence operations and planning can be appropriately analyzed through gaming, and which aspects can be appropriately analyzed through different forms of modeling. The project also examines the synthesis of deterrence gaming and modeling, how the results of gaming can inform deterrence modeling, and how modeling can shape deterrence gaming.

The SMA Deterrence project explored the methodologies and potential contributions of nine distinct data collection, modeling, and wargaming approaches. It addresses both their relationships to each other in support of deterrence planning, and their ability to directly support the deterrence assessment and planning process employed by U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM). The approaches included in the study include:

- The current practice employed by the Strategic Deterrence Assessment Lab (SDAL) at STRATCOM to develop analysts and documents with deep understanding of the decision making environment of an adversary, as well as that adversary’s decisions of interest to the United States. It uses a qualitative cost-benefit-analysis methodology.

- The capability analysis approach used by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) focused on assessing a particular actor’s ability to develop, manufacture, and proliferate a specific capability.

- The extended open source elicitation analysis employed by the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) which looks to collect qualitative data concerning the reactions and perspectives of the people themselves on an issue. This is done through a series of interviews with regional experts who have studied the area in question.

- The Gallup World Poll which characterizes countries’ thoughts on economic and social issues through surveying individuals in over 150 countries.

- The causal diagramming and system dynamics approaches as used by PA Consulting to model entities and their relationships initially through causal diagrams and then through equations that capture historical relationships, to explore causality and the driving factors of actors’ decisions.

- The strategic wargame approach used by the ODNI-NIC and their contractor SAIC which attempts to simulate a series of events and players’ reactions to gain insight into motivations and effects of particular occurrences; they allow the government to look at strategic and operational issues in a very non-threatening way before a crisis occurs.

- The subjective decision analysis approach employed by the NSI team which uses a cognitive decision approach to develop an understanding of how an actor’s interests and perceived options, as well as those attributed to perceived rivals, affect its decision making and behaviors.

- The social network analysis approach employed by the NSI team which focuses on gaining a holistic view of how people are connected through modeling social structures.

- The GLASS (Gallup Leading Assessment of State Stability) stability model employed by Gallup

which estimates the potential for latent instability or unrest, and traces the instability back to its causes, through a model built on accurate poll data within the country(ies) of interest.

In order to achieve the program objectives, the study incorporated a limited analysis of a specific deterrence scenario. The extended open source elicitation, capability analysis, and Gallup World Poll were used as data generation methods. The causal diagramming and system dynamics model, subjective decision analysis, social network analysis, GLASS model, and regional wargame were used to analyze various aspects of the deterrence scenario. In addition, a methodology and integration study was conducted using the current SDAL practice as a baseline. This study examined the utility, costs, and means of integration of the approaches exercised in the program as well as seventeen additional data generation and modeling approaches of potential relevance to deterrence analysis and planning.

This Summary Report provides an overview of the key analytic and methodological findings of the project. Detailed descriptions and the complete reports and products of the expert extended open source elicitation, causal diagramming/system dynamics, subjective decision analysis, social network analysis, GLASS modeling, as well as the overall Methodology & Integration study are provided as appendixes to this report. The results of the wargame are contained in a separate classified report at the SECRET level.

Rich Contextual Understanding of Pakistan and Afghanistan: Helmand Deep Dive.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A., Canna, S., et al. (NSI, Inc).

The objective of Helmand Deep Dive Development and Governance Workshop was to examine academic works and newly generated data and models and to develop guidelines and recommendations for low-cost development project implementation. The Helmand Deep Dive effort focused on water, governance, reconstruction, and job creation.

Eleven independent teams assessed various aspects using a common data set.

- Cultural Geography Modeling (LTC Dave Hudak, TRAC)

- Helmand Causal Frameworks (Tom Mullen, PA Consulting)

- Complex Adaptive System Approach (Anne-Marie Grisogono and Paul Gaertner, Australia Department of Defence)

- SOCOM SOC-PAS Helmand Analysis (David Ellis)

- ONR Helmand Ethnography (Rebecca Goolsby, Tracy St. Benoit)

- USAF – MCIA -Rand Helmand Analysis (Lt Col Steve Lambert, Ben Connable)

- JIEDDO/MITRE (Ken Comer, Nina Berry, Brian Tivnan)

- Department of State (Gina Faranda)

- Gallup surveys including POLRAD and GLASS (Tom Rieger)

- Culturally-Attuned Governance and Rule of Law (Ellee Walker)

- Sentia Group, Senturion Model (Brian Efird)

- PA Consulting, Causal Diagram (Tom Mullen)

Other presenters were invited to present important findings in their area of expertise including:

- John Wood (NDU)

- Tom Gouttierre (UNO)

- Abdul Raheem Yaseer (UNO)

- Abdul Assifi (UNO)

- Joseph Brinker (USAID)

- David Champagne (4th POG)

- Jean Palmer-Moloney (USACE-ERDC)

- Pete Chirico (USGS)

- Alex Dehgan (USACE-ERDC)

- Lin Wells (NDU)

- Captain Wayne Porter (JCS)

- Jeff Knowles (USDA)

The workshop addressed several key issues in development and governance including the economy, agriculture and irrigation, water security, Iran, security, and popular support for the Taliban. The workshop also reviewed the Civilian Conservation Corps and Distributed Essential Services-Afghanistan plans. The findings discussed below are compiled from many of the models and research efforts listed above. Page numbers from the workshop proceedings are listed where appropriate for easy reference.

Collaboration in the National Security Arena: Myths and Reality – What Science and Experience Can Contribute to its Success.

Author | Editor: O’Connor, J. (DHS), Bienenstock, E., et al. (NSI, Inc).

The purpose of this compendium of white papers is to explore various perspectives on the state of the art in our understanding of collaboration, including insights on the key factors that influence the who, what, when, where, and how of this topic. Collaboration traditionally refers to multiple people or organizations working towards common goals, but there are many other perspectives and definitions. The objective of this compendium is to identify and discuss the issues:

- how analytic tradecraft can be enhanced through collaboration

- when expansion of access to information take place and if this approach adds value to analysis

- how to facilitate collaboration within and across government organizations

- who collaborates and how do they collaborate to identify emerging threats

- what can be done to improve analysts’ ability to understand and apply social and behavioral science methods and findings.

The basis for all assertions will be given from both scientific and practical bases and areas of dissent and debate will be noted in the papers.

By way of background, this compilation was created after completing a Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) effort during 2008 to develop approaches to anticipate rare events such as the nexus of terrorism and WMD. That effort highlighted the fragility of the models and the need for a multi-disciplinary, multi-agency approach to deal with anticipating/forecasting, detecting and interdicting such events. That effort led to the following:

- Publication in November 2008 of a white paper entitled “Anticipating Rare Events: Can Acts of Terror, Use of Weapons of Mass Destruction or Other High Profile Acts Be Anticipated? A Scientific Perspective on Problems, Pitfalls and Prospective Solutions”

- Development of a concept for an Inter-Agency Limited Objectives Experiment (IA LOE) as described in the current white paper

This collaboration compendium is published as an adjunct to the aforementioned experiment.

In the months after the tragic events of September 11, 2001, it was discovered that indicators were there which could have led to the prevention of these terrorists’ acts. The 9/11 Commission Report, in looking at this issue, subsequently recommended “Unity of Effort” and a focus on Information Sharing. As we have thought through how best to move from a “need to know” to a “need to share” system, those human issues which contribute to the current “need to know” system have not changed. What has changed, however, is our understanding of human organizing processes and collaboration technologies.

This compendium of papers illustrates that theory, research, and applications are available for enabling collaboration. More importantly, collaboration technologies are now shaping organizing processes – whether our policymakers use them or not. These papers illustrate the breadth of issues involved in institutionalizing the concept of sharing that we now call collaboration. For readers new to this topic, the papers are ordered to minimize the time it will take to gather a working knowledge of the concept of collaboration, what the key constraints and enablers are to collaboration, and what potential paths forward entail.

Section one focuses upon Agency and Operational Perspectives. McIntyre, Palmer and Franks (Section 1.1) quote the President’s Memorandum for Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies on Transparency and Open Government, issued 21 January 2009, which states “Executive departments and agencies should use innovative tools, methods and systems to cooperate among themselves, across all levels of Government, and with nonprofit organizations, businesses, and individuals in the private sector.” McIntyre, et al., bring to our attention the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) Vision 2015 highlighting the need for establishment of “a collaborative foundation of shared services, mission-centric operations, and integrated management...”

The next two papers illustrate the military and law enforcement perspectives on collaboration. Harm and Hunt (1.2) note that collaboration is not a new thing for the military. In fact, Goldwater-Nichols empowered collaboration across defense agencies. The current generation of young military looks forward to their joint assignments. Harm and Hunt focus upon recent advances and evolutions in technology, culture, processes and people driving the current effort to create effective collaboration. Two interesting themes are now starting to emerge: collaboration is defined differently depending upon the culture of the organization, and, there is a need to start small with limited collaboration elements in order to build a functional and effective complex collaboration effort.

Kiernan and Hunt (1.3) point out the nexus between criminality and terrorism. The lessons law enforcement has already learned, as well as the tools applied to defeating social networks of criminals, are also applicable to the military’s fight against terrorism. The authors point out two successful collaboration environments – InfraGard and Defense Knowledge Online (DKO).

The last paper in this section is by Hilton (1.4). He starts with a compelling example of the benefits derived from collaboration enabled by technology during the crisis in the Republic of Georgia. Out of the lessons from this effort arose the concept of Teams of Leaders (ToL). ToLs are high-performing leader-teams whose members are from different organizations, cultures, agencies, or backgrounds and who each bring specific knowledge, skills and attitudes to the cross-culture JIIM leader-team. Components of ToL are Information Management, Knowledge Management and Leader Teams. The synergy amongst these three elements results in high performance. A theme that emerges in this paper, and throughout this compendium, is the idea that the least understood element of collaboration is the human element. The struggle for any organization is not information technology or knowledge management capabilities, but the identification and understanding of the human element in order to effectively apply them.

Section two of this compendium provides a scientifically based understanding of collaboration across multiple disciplines. Bienenstock, Troy and Pfautz (2.1) take on the unwieldy task of providing an overview of perspectives on collaboration. What comes out clearly is that there is a wide range of research, stretching across many disciplines in the area, but almost no overlap. Management and Social Sciences research have primarily investigated social structures and incentives that encourage or discourage collaboration. Computer Science research has focused on teamwork through technology. Additionally, computer design researchers have found that individual, dyadic, and group brainstorming should be encouraged, as well as cognitive conflict.

Research in the military and intelligence communities examine specific physical, virtual, and cultural structures that impact collaboration. The authors identify four critical questions for collaboration: 1) What kind of collaboration is required to meet goals; 2) What barriers exist in status quo; 3) What actions must be taken for facilitation; and, 4) what systems will best enable the actions. Bienenstock, Troy and Pfautz echo Hilton’s discovery: It is the people element that creates the dilemma for effective collaboration.

Next, Kuznar (2.2) notes the anthropological truism that humans are a social species and are interdependent upon one another for goods, services, security, and emotional support. He describes kin-based sodalities (collaborative societies) and non-kin based sodalities. Another theme emerges, which actually runs through all these papers: non-kin based sodalities are often voluntary associations that people create around some purpose. “The fact that voluntary associations are formed around a common purpose indicates that mechanisms of reciprocity are central to uniting a collaborative society...” Quid pro quo is a very old concept and is actually a reasonable way to organize.

Cronk (2.3) adds to the importance of this theme in his paper addressing an evolutionary perspective of collaboration and cooperation. Concepts such as kin recognition systems, cheater detection mechanisms, cooperator detection mechanisms, sensitivity to audiences, reputational concerns, coalitional awareness and theory of the mind suggest that human cognitive abilities may be the product of Darwinian selection in favor of cooperation.

Bienenstock and Troy (2.4) look at collaboration in terms of two basic dilemmas: social traps and social fences. Research is mature on social dilemmas and some findings echo those discussed throughout their paper. For instance, persistence and repeated interaction lead to emergent understanding of a shared fate and, eventually, trust – which contributes to eliminating both social traps and social fences. Also, network structure affects efficiency and promotes feelings of efficacy and a motivation to collaborate.

In the next paper (2.5), Stouder examines organizational studies. The progression of papers in this compendium illustrates that collaboration is studied from many different perspectives and is called many different things. Terminology aside, there is much science has to offer in guiding how information sharing and collaboration can be maximized. Studies have examined interactions and outcomes based on activity at individual, group, organizational, societal, national, and international levels. While the underlying intent of the studies may be to understand how to get people to work together/collaborate, how the research is implemented can result in findings that cannot, or should not, be compared.

Generalizations concerning collaboration must begin with a norming process on the terminologies and definitions. Just because performance on an assembly-line in Michigan increased when lights were added does not mean that it was the lights that increased production (those social scientists among you will recognize the reference to the Hawthrone studies). The problem of the third variable is very real. Empiricists like to get results based on manipulation of facts. However, there are times when the environment in which the empirical assessment is being made changes, and it becomes obvious that what was thought to be causing an outcome was really due to some third variable. Understanding a desired outcome via theory is definitely a more time intensive process, but when the health of entire societies may be on the line, the effort and thought required to test theory is more likely to lead to a consideration involving a rare event such as 9/11.

Stouder’s knowledge of the organizational research literature is a key place to start for the Limited-Objective Experiment (LOE) accompanying this compendium (see Article 4.1). Stouder provides a list of research questions that Bienenstock et. al., began; and authors of other papers add to it. For instance, what is the research seeking to understand – the process of collaboration (type, level, frequency, duration, intensity, variety)? Or, should research focus on the drivers or constraints on collaboration (environmental factors, organizational factors, events, etc.)? The quid pro quo theme emerges again. It appears that asking “What’s in it for me?” is a principle of human behavior as it applies to collaboration.

Heuer, Pherson and Beebe discuss analytic teams, social networks and collaborative behavior in the next paper (2.6). The rising use of Wikis and other collaborative software is building a more transparent and collaborative analytic environment. Hunt (2.7) looks at what can be learned from economics. Economics of engagement indicate that fun, trust and honor are critical components for collaboration success.

The last paper in this section (2.8) presents a Seven-Layer Model for Collaboration. This model is grounded in theory drawn from multiple disciplines. It represents the most comprehensive approach to laying out a means to test concepts of collaboration discovered during our compiling of this paper. Briggs’ Seven Layer Model begins with Goals and moves through Deliverables, Activities, Patterns of Collaboration, Collaboration Techniques, Technology and the Script Layer. Later in the compendium (Articles 4.6 & 5.3) a network architecture is described and it should not go unnoticed that this seven-layer theory and the layers of the mission fabric approach together make a good foundation for future theory development and empirical research.

Section three of this compendium addresses Common Barriers to Collaboration. Rieger (3.1) calls out imbalanced empowerment and accountability as key barriers. Regulatory and legal concerns play roles in making it hard to collaborate. A basic sense of fear of loss also plays a role. Empowerment is determined by whether someone has enough time to do their work, has the training to do it, has the materials and equipment, has open communications, and management support. If a worker puts any of his or her resources into performance, he/she is going to want to know there will be an acceptable form of reciprocity.

Heuer and Beebe examine Small Groups, Collaborative Pitfalls, and Remedies next (3.2). Small groups have been studied extensively across many domains. There are some basic principles of small group behavior which occur regularly (groupthink, polarization, social loafing, etc.). Heuer and Beebe point out that techniques have been developed which stimulate productive group behavior working with tendencies such as those listed above to improve performance. Palmer and McIntyre (3.3) make observations from the trenches about how to build a collaborative culture. The key challenges in building collaborative culture involve processes, technology, and behaviors. Again, the need for incentives for collaboration is noted.

Section four addresses What Applied Research has Learned about Collaboration. Numrich and Chesser (4.1) provide more detail on the Limited Objective Experiment (LOE) mentioned earlier and explain how the effort is embedded in the deeper need to understand and predict rare events. The LOE is designed to enhance existing analytic capability with new collaboration strategies and tools to make the process transparent to strategic decision makers.

The LOE has two parts: a Worldwide Rare Event Network (WREN) experiment and a companion US Air Force Academy (USAFA) experiment. In the WREN experiment a diverse community will attempt to characterize indicators of illicit terrorist activity against the US in a scenario developed by the FBI. Metrics collected during the experiment will include, but not be limited to, where players seek information, to whom they reach out for collaboration and how often, and what tools they tend to use. The USAFA experiment will involve a range of ages and experience (cadets and students plus law enforcement professionals) and the tools used in the second week will permit more visual interaction to measure whether that interaction enhances collaboration. This second experiment will make use of the mission fabric approach described in later papers (4.6 & 5.3).

Pherson and McIntyre (4.2) describe the Intelligence Community’s (IC) experience with operational collaboration. A great example of where new collaborative technologies are embraced is senior leaders who have started their own blogs. Another theme found across papers is perhaps best described here – there are explicit penalties for sharing information too broadly, including loss of employment, but no comparable penalties for sharing insights and information too narrowly. The idea that new collaboration efforts should start with small problems before they are applied to ‘life or death’ projects is brought up by Pherson and McIntyre. Key enablers to successful collaboration identified by the authors include consistent policies, technical and administrative infrastructure, engaged leadership, and use of collaboration cells.

Carls, Hunt and Davis (4.3) discuss Lessons about Collaboration in Army Intelligence. This is the first time that the importance of physical layouts has been specifically noted. It is also the first time that the trend for humans and computers to share reasoning workloads is noted (an element of the dilemma noted earlier involving the human element). Machines require explicit instructions in order to execute tasks involving collaboration. As such, when humans collaborate with machines, one side of a complex collaboration effort is held constant. This type of man/ machine collaboration may provide a base from which collaborative training for man/ man could begin. Further, broader understanding has often emerged from a leisurely stroll around a library or book store. Computers cannot “do” creativity, but humans have workload issues. Collaboration among humans alleviates some of the workload issue, but how do we move to a multi-faceted collaboration where the best of human groups can be brought out?

Meadows, Wulfeck, and Wetzel-Smith (4.4) next explore complexity, competence and collaboration. Identification of factors and collaboation support system design guidelines related to complexity dovetail with Bienenstock’s earlier discussion of the issues involved in researching collaboration. This paper serves as a great means to help merge the Briggs Seven-Layer Model and the framework presented by Pierce for collaboration engineering. The collaboration development process described in the paper is an excellent example of where collaboration started small and how it grew.

Lyons (4.5) provides an excellent review of empirical studies done by the Air Force looking at organizational collaboration and trust in team settings. Four dimensions of collaboration at the organizational level were found using a factor analysis: collaboration culture, technology, enablers (e.g., training), and job characteristics. Other findings relate to structures, processes and reward systems promoting information sharing via IT systems; importance of workspace design (physical layout) in information sharing; importance of individual agreeableness to perception of trust; and, negative communication decreasing performance.

Bergeron and Pierce, in paper 4.6, suggest creation of a means to instantaneously distribute and modulate control of information flow when dealing with security concerns of governmental organizations. Boehm-Davis (4.7) brings a wealth of research from the Human Factors Engineering (HFE) literature to light. HFE has worked to develop safe and effective performance over the last several decades to understand how man and machine have interacted for decades. Boehm-Davis shows there is a flow of knowledge needed to develop effective collaboration where group processes are understood, and also describes how those processes affect work performance and what the nexus is with technology. For example, studies show that if a procedure is put in place, certain aspects of team dynamics can be improved (e.g., checklists used by medical doctors). Boehm-Davis, taking an approach similar to Briggs Seven-Layer Model, also highlights the need to develop both vertical and horizontal models.

Moreno-Jackson (4.8) approaches issues of collaboration from the pragmatic point of view: sometimes the only way to get good collaboration is to involve a non-biased facilitator. MacMillan (4.9) raises the question of whether there can be too much collaboration. She provides findings from a 13-year study conducted by the Navy on Adaptive Architectures for Command and Control (A2C2). One of the key findings is that there is an optimal level of organizational collaboration and coordination for best mission performance – a level sufficient to ensure that mission tasks are accomplished, but not so great as to generate unnecessary workload. Further, she illustrates that it is possible to optimize organizational structures to achieve superior performance even when the number of times humans collaborate decreases. Boehm-Davis notes that the group dynamics literature has found that greater negotiation amongst group members leads to more adaptive groups over the long run.

There are definitions of collaboration throughout this compendium, but most include a need for cooperation towards a goal. The Navy research supports this definition by suggesting that if the goals for collaboration are well-understood and the mission well-specified, only then will there be better mission performance.

Linebarger’s paper (4.10) follows-up on the Navy findings by flipping the thought process around and suggesting that task-focused collaboration can be made more effective, especially if group collaboration patterns are recognized and explicitly supported by the surrounding environment and software system. Linebarger notes that collaboration always occurs if there is dialog. His research suggests that collaboration support improves quality and productivity, especially when the group has some control over how they are supported. Hall and Buckley (4.11) provide a delineated checklist for successful collaboration that has been used in the intelligence community to evaluate collaboration projects.

Section five of this compendium addresses “Potential Enablers for Collaboration.” Bronk (5.1) begins by identifying issues in management and sharing using techno-collaboration. He identifies three core principles for IT in collaborative government work: 1) collaboration tools should be easy to use, 2) collaboration tools should be entirely facilitated by the Web browser, and 3) collaboration solutions should be cheap, or even better, free, as far as users are concerned. Bronk suggests that if talented collaborators are cultivated and rewards systems put in place, appropriate technical tools will be found. He also notes that the quid quo pro in government is tied to the appropriation process and constitutional authority, thus explaining why IT adoption is sometimes difficult.

The next two papers address how IT might overcome some ‘people’ issues. First (5.2), Hunt and Snead discuss “Collaboration in the Federated Environment: The Nexus Federated Collaboration Environment (NFCE).” Essentially, the NFCE serves as a virtual social networking place that transcends the center and edges of its member networks yet facilitates members linking up when they have common specific goals. Interactions among any number of governmental organizations on any number of levels are enabled. The nation must enable people, information and processes to build, explore and exploit a networked federation of diverse organizations so that they can be easily aligned to make timely, transparent and collaborative decisions about adversary goals and behaviors. Again, it is important to put in place mechanisms to reward contributions to collective success.

Pierce (5.3) discusses a multi-dimensionality of collaboration. He describes the interplay between distributed collaboration, security, alignment and provisioning of services. He uses numerous helpful analogies to suggest there should be a paradigm shift in how information is shared and controlled technically. He calls this new approach the mission fabric.

Wagner and Muller (5.4) emphasize that trust occurs between two individuals not an organization. They draw from Gallup’s research to identify eight elements of collaborative success: complementary strengths, common mission, fairness, trust, acceptance, forgiveness, communication, and unselfishness.

Similar to the need sometimes for facilitators, noted by Moreno-Jackson, Pherson (5.5) suggests the use of Transformation Cells to institutionalize collaboration. This approach agrees with several other authors' observations that there must be a group with skills appropriate for the technologies, processes and behaviors needed, in order to enhance collaboration. Gershon (5.6) examines the scientific research on workspace design and provides blueprints for what might be the most effective designs for collaboration. He also provides illustrations that help the reader understand the key design issues.

Pherson provides another paper (5.7) that illustrates how to develop training courses on collaboration. The approach is comprehensive, noting differences in training requirements dependent upon where a collaborating analyst is in his/her career. He makes a strong argument for joint training because it enables analysts to build teams and networks, develop realistic incentives and metrics, and generate new collection strategies.

Von Lubitz (5.8) discusses the concept and philosophy behind development of Teams of Leaders (ToL) for complex defense and security operations. ToLs were developed because of the need for soldier-leaders who were flexible, adaptable, versatile, and comfortable in operating within the complex setting of Joint Inter-agency, Inter-government, and Multi-national (JIIM) operations.

Finally, Egan and von Lubitz (5.9) discuss the need to include lawyers in groups responding to crises. The Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (MSEHP) helped to organize trans- boundary issues associated with such events as the H1N1 public health emergency, but was more often used to focus on technical challenges. As policymakers worked through crises using MSEHP it became evident that the causes of poor responses were, actually, legal challenges. Three such issues were state sovereignty, definition of response roles, and respect for the federalist process. ToLs, discussed in earlier papers (1.4 and 5.8), which include lawyers, are a means to broaden leadership and to establish a decision-making base that spans the traditional agency and level-of-government boundaries, and generates a collaborative response. The authors emphasize that conflicting laws, jurisdictional domains, and the fear of litigation are present in every decision. As such, it makes sense to add the justice system into all the action already being handled by executive and legislative means.

As described in the 9/11 Commission Report, effective collaboration is a must if we are to prevent other such tragic events. This compendium takes a significant step toward integrating information from many different disciplines and environments in order to develop a field of research on collaboration. Through a more in-depth, empirically-based understanding of the issues, human collaboration can drive the development of new and/or improved technologies and organizational structures/processes.

What can happen if government information holders collaborate? The events of September 11, 2001 illustrate what can happen if they don’t.

Contributing Authors

Jennifer O’Connor (DHS), Chair, Elisa Jayne Bienenstock (NSI), Robert O. Briggs (UNO), Carl "Pappy" Dodd (STRATCOM/GISC), Carl Hunt, (DTI), Kathleen Kiernan (RRTO), Joan McIntyre (ODNI), Randy Pherson (Pherson), Tom Rieger (Gallup), Sarah Miller Beebe (Pherson), Keith Bergeron (USAFA), Elisa Jayne Bienenstock (NSI), Deborah Boehm-Davis (GMU), Robert O. Briggs (UNO), Chris Bronk (Rice), Kerry Buckley (MITRE), Joseph Carls (ret), Nancy Chesser (DTI), Lee Cronk (Rutgers), Bert Davis (ERDC), M. Jude Egan (LSU), Justin Franks (ODNI), Nahum Gershon (MITRE), Tamra Hall (MITRE), Col Craig Harm (NASIC), Richards Heuer, Jr. (Consultant), LTC Brad Hilton (US Army), Carl Hunt (DTI), Kathleen Kiernan (RRTO), Larry Kuznar (NSI), John M. Linebarger (Sandia), Joseph Lyons (AFRL/RHXS), Jean MacMillan (Aptima), Joan McIntyre (ODNI), Brian Meadows (SPAWAR), Victoria Moreno-Jackson, (Nat'l Assoc for Community Mediation), Gale Muller (Gallup), S. K. Numrich (IDA), Jennifer O’Connor (DHS), Douglas Palmer (ODNI), Stacy Lovell Pfautz (NSI), Randy Pherson (Pherson), Terry Pierce (DHS & USAFA), Tom Rieger (Gallup), Ned Snead (IDA), Michael Stouder (GWU), Kevin K. Troy (NSI), Dag von Lubitz (MedSMART), Rodd Wagner (Gallup), Sandy Wetzel-Smith (SPAWAR), Wally Wulfeck (SPAWAR)

Social Science Modeling and Information Visualization Workshop.

Author | Editor: Canna, S. & Popp, R. (NSI, Inc).

The Social Science Modeling and Information Visualization Workshop provided a unique forum for bringing together leading social scientists, researchers, modelers, and government stakeholders in one room to discuss the state-of-the-art and the future of quantitative/computational social science (Q/CSS) modeling and information visualization. Interdisciplinary quantitative and computational social science methods from mathematics, statistics, economics, political science, cultural anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, and modeling and simulation - coupled with advanced visualization techniques such as visual analytics - provide analysts and commanders with a needed means for understanding the cultures, motivations, intentions, opinions, perceptions, and people in troubled regions of the world.

Military commanders require means for detecting and anticipating long-term strategic instability. They have to get ahead and stay ahead of conflicts, whether those conflicts are within nation states, between nation states, and/or between non-nation states. In establishing or maintaining security in a region, cooperation and planning by the regional combatant commander is vital. It requires analysis of long-term strategic objectives in partnership with the regional nation states. Innovative tools provided by the quantitative and computational social sciences will enable military commanders to both prevent conflict and manage its aftermath when it does occur.

The need for interdisciplinary coordination among the academic, private, and public sectors, as well as interagency coordination among federal organizations, is critical to solving the strategic threat posed by dynamic and socially complex threats. Mitigating these threats requires applying quantitative and computational social sciences that offer a wide range of nonlinear mathematical and nondeterministic computational theories and models for investigating human social phenomena. Moreover, advanced visualization techniques are also critical to help elucidate – visually – complex socio-cultural situations and possible courses of action under consideration by decision-makers.

These social science modeling and visualization techniques apply at multiple levels of analysis, from cognition to strategic decision-making. They allow forecasts about conflict and cooperation to be understood at all levels of data aggregation from the individual to groups, tribes, societies, nation states, and the globe. These analytic techniques use the equations and algorithms of dynamical systems and visual analytics, and are based on models: models of reactions to external influences, models of reactions to deliberate actions, and stochastic models that inject uncertainties. Continued research in the areas of social science modeling and visualization are vital. However, the product of these research efforts can only be as good as the models, theories, and tools that underlie the effort.