SMA Publications

NSI maintains an extensive Publications archive of government-sponsored research and analysis products, various research efforts from our professional and technical staff, and a variety of corporate news items. The government-sponsored products are maintained on behalf of the US Department of Defense (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) program and address challenging national security problems and operational imperatives.

Author | Editor: Vern Liebl (Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning [CAOCL]); Yager, M. (NSI, Inc.)

This publication was released as part of the SMA project, “CENTCOM Regional and Population Dynamics in the Central Region.” For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Invited Perspective Preview

Note: This assessment was written before the death of Sultan Qaboos on 20 January 2020.

While the death of Sultan Qaboos is inevitable, the succession will likely fall well within the purview of the Basic Law and will be done with minimal national or regional disturbance. Who that successor will be and the ability to navigate and lead as Sultan Qaboos has done for 49 years is at this time unclear. It is very likely that the people of Oman will express a desire for greater local and regional self-governance as well as more freedom of expression and the rolling back of restrictions on the cybersphere, but for actual internal violence, there is no way to predict this.

Author: Dorondo, D. (Western Carolina University)

This publication was released as part of the SMA project, “CENTCOM Regional and Population Dynamics in the Central Region.” For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Introduction

In 2020, the States of the European Union (EU), as well as NATO’s European members and those States not enjoying membership of one or both organizations (e.g. the United Kingdom, Austria, Switzerland, and others), confront a serious multi-faceted challenge. This challenge takes the form of popular radicalization and mass migration (PRMM) of both refugees and non-refugee migrants originating in the portion of US Central Command’s Area of Responsibility (CENTCOM AOR) located in the Middle East and Central Asia and by extension into North Africa within the AFRICOM AOR.

This analysis examined specifically the concerns of the States of the EU2 + 1 (the United Kingdom, France, and the Federal Republic of Germany) and the other States of German- speaking and East Central Europe (GS-ECE). The latter include German-speaking Austria and Switzerland but also Hungary, the Czech Republic/Czechia, Slovakia, and Poland.

In varying degrees, but nonetheless consistently, these States view PRMM as posing: 1) a serious potential (or actual) Islamist terrorist threat to their national security (despite the fact that not all refugees or migrants are Muslim), and 2) an increasing likelihood for generating potential (or actual) socio-political instability in their domestic affairs.

To the degree to which PRMM is exacerbated by Russia’s military action in support of Syria in the latter’s civil war (the term is used generically), PRMM may be viewed as fostering Russia’s larger geo-strategic objectives of causing the greatest possible weakening of both the EU and NATO. Further, to the degree to which current Russo-Turkish cooperation continues— and Turkish-EU/NATO estrangement lasts—Turkey may well continue to serve as the principal corridor through which PRMM may be “exported” into Europe via Greece and the Balkans.

Key Findings

- Historically conditioned attitudes in the EU2 + 1 and GS-ECE complicate effective and rapid responses, whether national or collective, to PRMM.

- Barring major “Black Swan” events, EU2 + 1 and GS-ECE will continue to stress the importance of an international rules-based, preferably UN-led, effort to mitigate PRMM insofar as it threatens Europe directly. This would include on-site de- radicalization efforts in MENA itself and anti-mass migration efforts both on the EU’s borders and within individual States.

- EU2 + 1 and GS-ECE participation in a US-led “coalition of the willing” to mitigate PRMM is unlikely. Of the States in question—based upon the examples of the Sahel, the Mediterranean, Iraq and Afghanistan—exceptions might be found in the United Kingdom, France, and Poland. German participation in any large-scale combat role or safe-zone protective function is unlikely given both the current “lame duck” status of Chancellor Angela Merkel in the run-up to national elections currently scheduled for 2021 and other domestic concerns.

Authors: Derek Jones (Valens Global), Madison Urban (Valens Global), & Dr. Kevin D. Stringer (General Jonas Zemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania)

This publication was released as part of the SMA project “21st Century Strategic Deterrence Frameworks.” (SDF) For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Publication Preview

At the core of the United States 2022 National Defense Strategy is the concept of integrated deterrence, using the full range of tools of statecraft to convince a potential adversary that an undesired action is not worth the cost. As technologies progressed after World War II, scholars and practitioners developed theories of deterrence centered around the destructive power of nuclear weapons and overwhelming conventional force. However, a new model of deterrence, one centered around irregular capabilities, ought to be further explored. This article outlines current major deterrence theories and strategies and proposes a conceptualization of irregular deterrence across the cooperation, competition, and conflict spectrum.

This publication was released as part of the SMA project “21st Century Strategic Deterrence Frameworks.” (SDF) For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Research to Identify Drivers of Conflict and Convergence in Eurasia in the Next 5-25 Years: Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) Summary Report.

Author | Editor: Canna, S., Bragg, B., Desjardins, A., Popp, G. & Yager, M. (NSI, Inc).

From July through November 2015, NSI employed its Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa) methodology to systematically interview 26 subject matter experts in support of a Strategic Multilayer Assessment effort to research and identify drivers of conflict and cooperation in Eurasia in the next 5-25 years. Representatives from the United States European Command (EUCOM) provided 37 questions to guide the interview effort (see Appendix A). This report summarizes SME knowledge and insights on these questions—grouped into nine chapters.

The executive summary focuses on the issue of deterrence, which was a recurrent theme amongst the expert responses. From a social science perspective, we first need to ask, what behavior do we want to deter (i.e., Russian “aggression”?) and why (i.e., how does deterrence serve US strategic interests?)? The executive summary focuses on the element of conflict and cooperation with Russia: deterrence, strategic interests, and implications.

Background

ViTTa is a virtual network of trusted subject matter experts, unconventional thinkers, brightest minds, foreign voices, and varied perspectives. ViTTa Subject Matter Experts enable NSI to craft timely and cost effective analyses of critical and complex problems.

Under tasking from USEUCOM, the effort identified emerging Russian threats and opportunities in Eurasia (with particular emphasis on EUCOM AOR countries). The study examined future political, security, societal and economic trends to determine where US interests are congruent or in conflict with Russian interests, and in particular, detect possible leverage points when dealing with Russia in a “global context.” Of particular interest were Russian perceptions of US activities in Eastern Europe and what impact (positive or negative) those activities are having on deterring Russian aggression in the region. Additionally, the analysis considered where North Atlantic Treaty Organization interests are congruent or in conflict with Russian interests.

Strategic Interests

Russia

Russia’s rhetoric and actions suggests that it is dissatisfied with the international status quo. It wants a return to Russian greatness in the international community. Expert opinion indicates that, for Russia, a return to greatness would comprise the following elements:

- international prestige and recognition;

- acknowledged sphere of influence in near abroad; and

- economic, military, cultural, and political power and vitality.

These desires are driving Russian domestic and foreign policy and are clearly entangled with Russia’s aggressive foreign policy actions, including the annexation of Crimea, military intervention in Ukraine, and support for Bashar al Assad in Syria. From its perspective, Russia is hindered in achieving its strategic interests by international and domestic factors including Western attempts to “keep it down” (e.g., NATO enlargement, sanctions, etc.), low oil prices, slow economic growth, and demographic decline.

United States

The United States Government (USG) has multiple objectives in the EUCOM area of responsibility (AOR)—with regional stability being arguably the foremost among them. To achieve this end, the experts felt that USG decision-makers have reverted into a Cold War mindset that engenders a reflexive preference for containment of Russia. They pointed to efforts to expand NATO—an organization established after World War II specifically to contain the Soviet Union—and economic sanctions as evidence of a preference for containment over engagement. However, experts were evenly divided over whether containment or engagement strategies would be most effective in restoring stability in Eurasia. This summary does not weigh in on the optimal strategy, but highlights two competing pathways to stability addressed by the expert elicitation effort: containment and engagement.

The Centrality of the Russian Economy

Few issues exist in Russia that have greater potential to destabilize the country by creating internal dissatisfaction among both the elite and the general population than the economy. Experts felt USG leaders do not fully appreciate the importance of Russia’s economy as the driver of Russian decision- making. The USG uses sanctions as a sort of tier two punishment—below the threshold of military force. However, in Russia, sanctions are viewed essentially as an act of war. There is a mismatch in perception between the USG and the Russian government and people about economic levers of power that is fundamental to this study.

Experts noted that economics dominates Russian media and government speeches, more so than Russia’s actions in Ukraine, Crimea, and Syria—as is supported by thematic analysis conducted by Dr. Larry Kuznar. Even absent economic sanctions, Russia’s economy is in serious jeopardy due to low oil prices, lack of economic modernization and diversification, and a shrinking workforce. It is important to remember that Putin’s initial popularity and legitimacy rested on strong support for his policies that resulted in economic growth from 1999-2008.

The USG sees Putin as a nationalist and, therefore, aggressive, but Putin does not draw his support from a sense of populist nationalism; he draws his support from economic reform and improvement. It is easy to get caught up in the mistaken belief that ultranationalism is driving Russia aggression, but this term is often misused in the USG. Ultranationalism is not influential in Russian politics, but nationalism is. Experts felt this is concerning because by punishing Russia economically, the West is undermining both the economic and political stability of the nation. So the question then becomes, what does the West fear more: a failed Russian state or a stable, powerful Russia?

Containment and engagement actions taken by the United States (both USG as a whole and EUCOM more specifically) can influence Russian stability. Each of these paths create both risk and opportunity for US interests and has implications for EUCOM engagement activities in the EUCOM AOR as a whole.

Central Question

Pathways

Is it better for the USG to have a stable, strong, and prosperous Russia (satisfied) or an unstable, contained, and weak Russia (unsatisfied)?

The first thing we need to know is what conditions are associated with each type of Russia? That is, what do we know about what Russia needs to make it stable/satisfied, and what do we know about is making it unstable/unsatisfied?

Because this analysis represents a thought exercise, and requires some simplification, we associate US engagement and cooperation with Russia leading towards a satisfied Russia versus continued US containment and conflict with Russia leading towards an unsatisfied Russia. We then explore the risks and opportunities associated with each pathway.

The second part of this thought exercise is to evaluate the implications (at the extreme end of the spectrum) of these pathways for US interests.

Engagement/Satisfied Russia

Benefits

A stable, economically and politically strong Russia may better serve USG strategic interests as they relate to stability in the Middle East, the shake up of Western-leaning Eastern European nations, the balancing of East and West, and the development of the Arctic. Experts believe the West may be able to find common ground on these issues through a more cooperative relationship with Russia, but an uncooperative Russia could—and does—act as a spoiler for many of these critical issues.6 Furthermore, a more cooperative relationship with the West undermines Putin’s ability to deflect blame for domestic problems—although at least one expert stated that Putin would always be able to spin the relationship in his favor given his control of the media. Because of this, experts believe the only effective mechanism of communicating to Russian elite and the population a willingness to engage is through action—not words. By focusing on engagement vs. conflict with Russia, the West erodes Putin’s ability to message that the USG is the enemy of Russia. It opens the door for the population and elite to see the potential for economic prosperity through cooperation.

Risks

Additionally, while a satisfied Russia may serve US long-term, strategic interests, this pathway raises significant concerns for Western interests: losing face and fueling Russian ambitions. An overly confident Russia might mistake Western cooperation for weakness and use its new political, economic, and social stability to challenge the international system. This poses a difficult conundrum where long-term US strategic interests are best pursued in a way where any concessions made could be perceived or framed by adversaries and competitors as weakness. The significant Russia information operation complex will likely play up these developments as a win for Russia at the expense of the West.

Containment/Unsatisfied

Benefits

The benefits of a contained Russia include the maintenance of the status quo for the international community in terms of continued US leadership, the reduction of a conventional military Russian threat to Europe, and support of US allies.

Risks

While a contained Russia may serve Western interest in maintaining the international status quo, this policy runs the risk of undermining the political and economic stability of Russia in the longer term. A perfect storm of a prolonged, weak economy; rising nationalism; significantly decreased quality of life for Russian citizens; and restricted economic opportunity for the political elite may result in a weak or failed state or the replacement of the current administration with one that is less stable or favorable to the West. State failure and political change in Russia is often abrupt, leaving little time for the West to respond or alter its strategy. Furthermore, the lack of any clear successor to Putin means we have scant information regarding the type of leader – and thus policies – that would ensue.

Additionally, Western efforts to contain Russia may increase its reliance on gray zone activities, increasing conflict via proxies, and increased reliance its nuclear threat if its conventional military and other means of influence and deterrence fail. Experts believe that containment of Russia may have unintended consequences fore US strategic interests and regional stability.

Levers of Influence

Third we need to explore the effects of US levers of influence, particularly sanctions and NATO enlargement.

Sanctions

The more force we apply to economic levers (such as sanctions), the more we cause Russia to turn away from the West towards Iran and China. Right now, Russia sees itself as more European than Asian, and would prefer to retain ties to the West. However, sanctions are pushing Russia to form alliances with countries outside the sanctions regime, countries we do not want to see getting more powerful.

Sanctions may also weaken Putin’s legitimacy, driving him to increase the use of nationalism and aggressive foreign policy to shore up his political support. This may provoke a geopolitical crisis that the West would like to avoid. In the absence of sanctions, Putin is not likely to give up his nationalism rhetoric, but it might give him options other than aggressive actions, to enhance his legitimacy.

NATO Enlargement

NATO was expressly created to contain the Soviet Union. It is not hard to imagine why Russia perceives NATO expansion as a real threat—particularly expansion into the area Russia considers to be its near abroad.

The danger of NATO expansion in this day and age is that power is increasingly about generating political will and less about sheer capacity. Experts pointed out that expansion has broadened NATO’s membership, but in doing so has weakened the organization’s collective political will. NATO has not demonstrated the political will to defend its newer states from aggression, weakening the effectiveness and credibility of the alliance—although some SMEs challenged this assertion pointing to the recent increase in NATO military exercises. Taken together, these factors point to a critical weakness at the heart of NATO: as the alliance grows bigger, member states’ interests become more diversified, making it increasingly difficult to command unified action in the event of external aggression.

Conclusion

When Russia cannot express its power economically, it seeks to do so militarily (not so dissimilar to Iran). The implication of this for EUCOM is that there are risks and benefits to both the containment and engagement pathways for US strategic interests. This summary report covers many issues facing decision makers in the EUCOM AOR and dives deep into expert knowledge from multiple disciplines and perspectives to challenge assumptions and provide nuanced understanding of the issues.

Effects of Investment on Pathways to Space Security

Author: Dr. John Stevenson (NSI, Inc.)

[Q10] Does substantial investment and heavier commitment by both governments and commercial interests provide an avenue of approach for space ‘security’ and disincentive for kinetic military action?

Summary Response

Expert contributors wrestle with three factors in answering this question:

• Whether spending more will improve security and disincentivize kinetic action.

• Whether either or both commercial and government actors should spend more.

• If both, then whether commercial and government actors should do so independently or through partnership.

80% of the expert contributors affirm that increased spending would provide an avenue of approach for space security and disincentive for kinetic military action. The remaining 20% diverge on why they do not believe that spending would improve space security. Some contributors aver that the effect of spending on security and kinetic action is conditional on the type of adversary, or if the rules of the road resulting from increased investment reduced pathways toward inadvertent escalation, whereas others argue that increased spending increased the number of targets and increased the possibility of wasteful spending.

Almost every contributor supporting increased spending as a disincentive for kinetic military action argues that spending from both commercial and government actors would have the predicted positive effects, and that neither type of actors’ spending would be more efficacious. Only one contributor, Group Captain (Indian Air Force ret.) Ajey Lele of the Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, suggests that one type of actors’ spending—state actors—would have greater impact.8 Finally, although most contributors did not specify whether they believe the positive effects from increased investment required partnership, or would occur even if commercial and government actors invested independently of each other, the few contributors that accounted for this parameter specifically mentioned public-private partnerships as the most effective vehicle for investment.

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Author: Dr. Frank Zagare (University of Buffalo)

This publication was released as part of the SMA project “21st Century Strategic Deterrence Frameworks.” (SDF) For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Publication Preview

During the cold war the conventional wisdom was that an all-out war between the United States and the Soviet Union was all but precluded. The key to this strategic nirvana was a carefully calibrated balance of strategic weapons and the high costs associated with nuclear conflict. The policy that was credited to

bringing this state of affairs about was labeled Mutual Assured Destruction, or MAD. Each side threatened to obliterate the other if it were attacked. Based on this logic, some strategic thinkers argued for the selective proliferation of nuclear weapons, to Iran for example, in order to stabilize the relationship between two otherwise hostile states (Waltz, 2012). Others argued that Ukraine was misguided to have

surrendered its nuclear arsenal in 1994 (Mearsheimer, 1993).

However, the theory underlying this policy, sometimes called Classical (or inappropriately, rational) Deterrence Theory, does not pass the test of strict logic (Zagare, 1996). It assumes, simultaneously, that the players are both rational and irrational—rational when they are being deterred and irrational when they are deterring. Bernard Brodie, considered by many to be the seminal deterrence theorist, put it this way: “For the sake of deterrence before hostilities, the enemy must expect us to be vindictive and irrational if he attacks us” (Brodie, 1959, p. 293). The noted game theorist, Thomas Schelling, who was the recipient of the 2005 Nobel Prize in economics, also argued that nuclear deterrence only worked if an

aggressor was convinced that its opponent would retaliate—irrationally. As he wrote so succinctly: “… another paradox of deterrence is that it does not always help to be, or to be believed to be, fully rational, cool headed, and in control of one’s country.” In other words, it was rational to be irrational (Schelling, 1966: 37).

Logically inconsistent theories are prima facie seductive, yet fatally flawed. They invite theorists with a point of view to draw almost any conclusion, including its exact opposite, depending on the analyst’s policy preferences. So, it is unsurprising that other classical deterrence theorists, working from the same set of assumptions, oppose disseminating nuclear weapons to Iran or to any other state actor including Ukraine.

To overcome the logical inconsistency of Classical Deterrence Theory, Marc Kilgour and I have constructed an alternative theory that insists that the players are rational (or purposeful) at all times. We call it Perfect Deterrence Theory (Zagare and Kilgour, 2000). In this alternative specification there are certain conditions under which wars cannot be avoided. For example, it is possible that Russia may still have invaded Ukraine even if the Ukrainians had not given up their nuclear capability once the Soviet Union broke up. Low level conflicts are very difficult to deter, as are situations where one state seeks to deter an attack on an ally. Worse still is the propensity of these conflicts to escalate. Sunk costs may play a role here. But so may uncertainty about the extent of resistance, if any. Risk taking leaders are the most dangerous.

For obvious reasons, both Classical Deterrence Theory and Perfect Deterrence Theory have focused on dyadic relationships. It is clear, however, that that focus now needs adjustment. In the current environment, there are currently two dissatisfied major nuclear powers that would prefer, ceteris paribus, an adjustment of the rules that support the international political and economic system as it operates today. At the global level, then, a key question is how a defender of the status quo might deal with two potential challengers.

The answer to this question depends, in part, on the relationship of the two challengers. There are three

possibilities:

- Both dissatisfied actors act independently in separate disputes. If this is the case, there is no need for

new theory. Current theory still applies. Assuming that the conditions needed to deter the most

problematic case are met, these same requirements would suffice to deter the less problematic case

as well. The assumption of independence implies that it is highly unlikely that the two disputes would break out simultaneously. - Both actors operate as one in a tacit alliance. Again, current theory can handle this case, as it did

during the Cold War. - The second (secondary) actor (Challenger 2) becomes a player if and only if the primary actor

(Challenger 1) upsets the status quo. It is clear that it is this special situation that requires further

scrutiny.

The purpose of this essay is to extend the logic of Perfect Deterrence Theory to the third case, which, for expository purposes, will be referred to as the three-body problem.

Russia and the Arctic.

Author | Editor: Levis, A. & Elder, R. (GMU).

The receding of the Arctic ice presents the Russian Federation with complex opportunities and challenges, both domestic and international. Russia is investing heavily in developing the infrastructure on its Arctic coastline to support both destination shipping in the Arctic and transit shipping through the Northern Sea Route (NSR) between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. The estimated resources in the Russian Arctic Region in energy and minerals are very large but their extraction requires major long term investments and such investments are high risk ones because of harsh weather and the insufficiency of the existing infrastructure; some of the existing infrastructure is degrading because of the thawing of the permafrost. Russia’s effort to modernize its Armed Forces has included the creation of the Arctic Joint Strategic Command that includes the Northern Fleet. Old bases are being re‐opened and new bases are created in the Arctic region. These developments in the Arctic show clearly that the Far North is expected to have a major role in the future of Russia not only for economic reasons but also as a common theme, a common narrative that resonates with the Russian people. It will be unwise to interpret all Russian actions in the Arctic as being statements to the West or to the East. It will be helpful if they are also interpreted in terms of internal domestic (and nationalistic) considerations.

Clearly, the Arctic plays a major role in the future of Russia not only for economic reasons but also as a common theme, a common narrative that resonates with the Russian people. It will be unwise to interpret all Russian actions in the Arctic as being statements to the West or to the East. It will be helpful if they are also interpreted in terms of internal domestic (and nationalistic) considerations.

ISIL Influence and Resolve.

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

During FY 2014, the SOCCENT Commander requested a short-term effort to understand the psychological, ideological, narrative, emotional, cultural, and inspirational (“intangible”) nature of ISIL. As shown below, the SMA1 team really addressed two related questions: “What makes ISIL attractive?” or how has the idea or ideology of ISIL gained purchase with different demographics; and “What makes ISIL successful?” or which of the organization’s characteristics and which of the tactics it has employed account for its push across Syria and Iraq.

The effort produced both high-level results and detailed analyses of the factors contributing to each question. The central finding was this: While military action might degrade or defeat factors that make ISIL successful, it cannot overcome what makes ISIL’s message and idea attractive. The complete set of products from the effort is available by request from Mr. Sam Rhem in the SMA office (samuel.d.rhem.ctr@mail.mil).

For the follow-on effort, the SOCCENT Commander has requested an effort to address the following question: Given that when the dust settles and some degree of durable stability has been established in the Middle East, it will no longer look as it did prior to the start of the Syrian civil war and the rise of ISIL; therefore, the question is what will the Middle East look like, and how is it likely to operate both within its own regional community and in interactions with external powers and actors, after the ISIL threat has been defeated and the Syrian Civil War has come to an end.

The articles in this white paper summarize work on going and completed by different SMA-affiliated teams in response to this request. The focus is primarily on one of the regional actors: ISIL and the nature of that organization’s interests, influence capabilities, support, and resolve. There has not yet been an effort to consolidate the insights presented by each of the pieces. Rather, they are presented as stand-alones from which analysts and practitioners might gain insight. A final project report including additional regional actors will be available from the SMA office in December 2015.

The question posed for follow-on SMA support to the SOCCENT Commander broadens the look at ISIL undertaken during the first phase, and considers the group in the context of regional dynamics. Essentially, this is a question about the relations embedded in the dynamic, multi-actor system that comprises the Middle East region, and will determine the outcome of regional events. Figure 2 represents the analytic model that serves as the framework for the larger study. It posits that how the system evolves over time is a function of the interests at stake for the actors, their ability to pursue those interests, and the alignment of interests between actors.

An individual actor’s ability to influence the outcome of regional events is a function of three resource factors: its capability, popular support, and resolve, relative to other actors in the system. However, how actors chose to influence the course of regional events will be a function of how well their interests can be met by specific event outcomes. We assume that actors will prefer outcomes that protect or further their interests.

The alignment of interests between actors will determine the set of potential outcomes for any particular regional or sub-regional event. However, common interests or alignments between actors may vary across events or conflicts; we cannot assume that a preference for the same outcome in one event will result in shared interests among the same actors in other events. While the alignment of actor interests determines possible outcomes, the distribution of actor capabilities, popular support, and leadership resolve across those outcomes will govern the likelihood that an outcome will emerge. The framework also accounts for the potential effects of exogenous factors on the region (such as environmental or demographic changes) and how these may influence the individual actors.

Analytic Framework

Evaluation of the range of possible futures that the region may see begins with identifying the relevant set of actors. The framework includes five types of actors:

- Status quo (ante bellum) regimes – current state governments within recognized borders (for example, the monarchy in Saudi Arabia, the elected parliament in Turkey);

- Parasitic organizations – such as trans-national criminal organizations that operate in the area;

- Government opponents – challengers to the status quo from within. This includes opposition parties or groups who are opposed to a current government but seek change through existing institutions, rather than regime change (e.g., the Iraqi List in Iraq; Labour in Israel);

- Regime opponents – groups fighting for significant change in the type of regime or political system either within or across existing borders (e.g., ISIL, Free Syrian Army); and,

- Population groups – many of whom have limited political or ideological interests but seek mainly to survive in the midst of the conflict ranging around them.

The ability of each actor to influence the evolution of the system toward different outcomes is a function of its relative capability, popular support, and resolve.

Capability. There are many types of capabilities that an actor might use to achieve its ends in a conflict. These include: material resources and coercive capabilities (e.g., money, weapons); non-physical means of influence or coercion (such as salient narratives and persuasive messages); a reputation for horrific violence; possession of territory; and alliances including external funding sources and the allegiance of local elites. Importantly not all influence capabilities are equally relevant to all conflicts or objectives. For example, the United States is certainly the world’s greatest military power, but may not have the non-physical influence capabilities needed to achieve its desired ends. Similarly, ISIL may have significant ability to control populations through the threat of horrific violence, but lack the organizational capability needed to occupy and control large population areas.

Popular Support. Some degree of popular support for or acquiescence to the programs or policies of an organization or government can be a critical enabler. Likewise, a population that does not see a leadership as legitimate or is at odds with its priorities can pose a significant barrier to action and place limits on the resolve of a government to sustain certain actions.

Resolve. Finally, a government or organization’s willingness or need to fight to the bitter end for an objective or principle has been shown to a deciding factor in achieving one’s preferred outcome in a conflict—even when capabilities are lacking.

The framework assumes that actors are motivated to protect and further their interests. To determine how an actor will apply its ability (capability, popular support, and resolve) to an event or conflict, therefore, we need to understand which of that actor’s interests are at stake in the context of a particular event or conflict. Once we identify those actor interests, they can be linked to a specific outcome, or outcomes, where we can then construct a map that specifies the sub-set of actors that prefer different outcomes and estimate the total resources and resolve behind each outcome. This is a critical element of the framework, as, by definition, the outcomes of conflicts are not the result of a single actor’s actions or desires, but are a product of the interactions of opponents. In other words, the forces that determine one or another future reflect the confluences of actors’ capabilities, resolve, and popular support. How stable that outcome is likely to be, however, will be determined not so much by the resources of those who support it, but the resources of those who oppose it. By considering the resources of the actors whose interests are blocked or destroyed by a particular outcome, we can also estimate the potential durability of a particular outcome. In effect, the framework posits that the outcome of an event will be a function of the preferences of the subset of actors with the greatest resources, while the durability of that outcome will be determined by the resources of those whose interests remain unfulfilled.

Contributing Authors

Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI), Barr, N. (Valens Global), Bedig, A. (Monitor-360), Canna, S. (NSI), Chinn, J. (Texas A&M), Eyre, D. (System of Systems Analysis Corps), Gartenstein-Ross, D. (Valens Global), Jensen, B. (Marine Corps University), Kluver, R. (Texas A&M), Kuznar, L. (Indiana University, Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Ligon, G. (University of Nebraska, Omaha), Miles, D. (TRADOC G-27 TBOC), Moreng, B. (Valens Global), Moreno, C. (TRADOC G-27 TBOC), Munch, R. (TRADOC G-27 TBOC), Norton, A. (Monitor 360), Parhad, R. (Monitor 360), Potter, P. (University of Virginia), Spitaletta, J. (JS/J-7 & JHU/APL), TRADOC G-27 OEL, Venturelli, S. (American University), Watts, J. (Noetic), Willcox, J. (System of Systems Analysis Corps), Worret (TRADOC G-27 TBOC), Wright, N. (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace)

[Q16] Which international actors currently have the greatest strategic risk in the space domain? What affordable non-space alternatives are there to mitigate or avoid that strategic risk? A Virtual Think Tank (ViTTa)® Report.

Author: George Popp (NSI, Inc.)

Summary Response

This report summarizes the input of 15 insightful responses contributed by space experts from National Security Space, industry, academia, government, think tanks, and space law and policy communities. This input includes expert contributions from US voices as well as non-US voices from Australia, India, Italy, and the UK. While this summary response presents an overview of key subject matter expert contributor insights, the summary alone cannot fully convey the fine detail of the contributor inputs provided, each of which is worth reading in its entirety.

International Actors with the Greatest Strategic Risk in the Space Domain

The consensus view among the expert contributors is that the United States is the international actor with the greatest strategic risk in the space domain.5 Contributors also identify several other international actors as having noteworthy levels of strategic risk in the space domain, albeit less than that of the United States. These actors include Russia, China, US allies, and nuclear powers, more generally.

Two consistent indicators of strategic risk in the space domain emerge across the contributors’ assessments and calculations of actors’ strategic risk:

- The actor’s level of dependence on space for critical national security, military, economic, and societal services and infrastructure.

- The actor’s level of space domain vulnerability, particularly in relation to the susceptibility and exposure of its space assets to threats.

The United States

The contributors generally align with Dr. Nancy Gallagher’s (Center for International Security Studies at Maryland) succinct assessment: The United States is the most capable space actor but also the most vulnerable. As the contributors from Harris Corporation reflect, the US has an “asymmetric advantage” in the space domain relative to other international actors, but it likely also has a correspondingly asymmetric level of strategic risk. Ultimately, Dr. Edythe Weeks’ (Webster University) ominous observation appears to ring true: “it’s frightening how much the US would be impacted by a space disruption.”

Strategic Risk from Dependence on Space

Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin) articulates a point that is echoed throughout the expert contributions: “the United States faces the greatest strategic risk because [its] society, economy, and way of life rely or depend upon access to and use of the space domain.” Several contributors6 point to the United States’ significant dependence on space for critical national security, military, economic, and societal services and infrastructure as a paramount reason for classifying it as the international actor with the greatest strategic risk in the space domain. For example, Indian Air Force Group Captain (ret.) Ajey Lele (Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses) conveys this rationale in his assessment. His calculation of strategic risk focuses on “the strategic challenges that a nation-state is facing in space and the dependence of that nation-state on space assets,” which leads him to conclude that “the US [has] more challenges than any other country.”

This dependence on space, alone, however, does not make the US entirely unique—many international actors, including all nuclear powers,7 depend on space for critical capabilities and services. What differentiates the US is that its dependence on space and space activity appears to be a magnitude above every other actor,8 and this does not appear likely to change any time soon.9 Moreover, contributors remind us that “space and cyberspace are interconnected domains tied into the [United States’] critical infrastructures” (Berkowitz), and “70% of the technology used in the US [today]…derives directly or indirectly from space technology and services” (Rossettini). These two points illustrate the magnitude of the United States’ strategic dependence on the space domain, and support Berkowitz’s conclusion that “unimpeded access to and use of space…is a vital national interest and a center of gravity” for the United States. Clearly, as Berkowitz suggests, “the stakes in space for the US are enormous.”

Strategic Risk from Vulnerability in Space

Contributors also point to space domain vulnerability, particularly the susceptibility and exposure of US space assets to threats, as a paramount reason for classifying the US as the international actor with the greatest strategic risk in the space domain. Historically, the United States’ investment in the space domain has been unmatched; since the 1950s, the US has invested more money into space activities than other international actors, and has developed more space assets and infrastructure. This investment and the legacy systems that it created certainly helped to establish the US as the leading international space power. However, because many of these systems were built at a time in which self- defense was not a design priority for US space platforms, it also means, as Lele observes, that the US is dependent on “more vulnerable targets” than are many other actors. The result is asymmetric risk in many scenarios in which another actor may challenge or act aggressively toward US space assets. Focusing in on this element of vulnerability, Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit) proposes assessing strategic risk from the “perspective of potential impacts as a consequence of losing space assets.” From this perspective, he concludes that “the US is definitely the nation with the highest risk.” Undoubtedly, a serious threat and/or challenge to US space assets could have significant, far-reaching impacts on US capacity and capability across every operational domain.

United States Allies

Contributors also point to US allies, in general, as having noteworthy levels of strategic risk in the space domain. Ultimately, the United States’ space domain vulnerabilities extend to its allies who rely and depend on US space capabilities, systems, and information for critical national security, military, economic, and societal services and infrastructure in their own countries. Therefore, if the US has the greatest strategic risk in the space domain, then US allies likewise have significant strategic risk as well, Harris Corporation contributors argue. Weeks echoes this rationale. She points to Mexico in particular as having noteworthy strategic risk, maintaining that Mexico is “inextricably intertwined with the US (i.e., whatever affects the US, affects Mexico)” in all domains, including space.

Runners-Up: Russia and China

Contributors also identify Russia10 and China11 as having significant strategic risk in the space domain, though less than that of the United States. This assessment holds whether considered from a dependence standpoint or a vulnerability standpoint. The contributors from Harris Corporation focus on the dependence on space assets and systems as a main indicator of strategic risk, assessing that, other than the US, “Russia has the most to lose today, but China is quickly approaching that level.” Evidence for this assessment comes from “look[ing] at the numbers of launches [and] the number of assets the Russians have in space versus what the Chinese have…and the amount of launches they’re doing per year,” which the Harris Corporation contributors suggest reveals that “China will quickly surpass Russia in capabilities at risk.” Rossettini considers Russian and Chinese space domain vulnerability, particularly exploring strategic risk from a “liability point of view.”12 From this liability-focused perspective, he assesses that Russia has significant strategic risk—likely even more so than the US, he suggests—and that Chinese strategic risk is growing as it increases its footprint in space.

China relies on space for critical national security, military, economic, and societal services and infrastructure. In fact, Dr. Krishna Sampigethaya (United Technologies Research Center) contends that China’s strategic risk in the space domain has already surpassed that of Russia. He explains that “among the rest of the world, China seems to exhibit [the] greatest strategic interest in space. It is viewed as a means to gaining prestige of space exploration and enhancing national security. China is also relying on their aerospace sector as a catalyst for a flattening economy.” All of this, plus what Sampigethaya describes as recent Chinese interest and investment in cyber advances in the space domain, epitomize “an ambitious space strategy” that will seemingly only continue to increase China’s strategic dependence on space in the years to come.

Affordable Non-Space Alternatives to Mitigate Risk

Several contributors reflect concern with the basic premise underlying the second part of this report’s question of focus: What affordable non-space alternatives are there to mitigate or avoid that strategic risk? Broadly, their concerns can be grouped into three schools of thought:

- there are no non-space alternatives;

- there are non-space alternatives, but they are not affordable; and

- there are non-space alternatives, but major space actors are not likely to consider them.

Despite these general concerns, the contributors do highlight non-space alternatives for mitigating or avoiding strategic risk in the space domain, with two general classifications of activities emerging: diplomatic activities and terrestrial alternatives.

Schools of Thought and Associated Caveats

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor (Orbital ATK) presents the thinking that, “to a large extent, there are no non-space alternatives any more than there are non-cyber, non-air, non-sea, or non-terrestrial risks. Western civilization depends on all these modes.” He suggests, therefore, that “most answers [to this question] will probably be to ‘robust up’ space systems themselves, not look for non-space alternatives.”

Conversely, Berkowitz highlights the viewpoint that “terrestrial alternatives exist for nearly all space force enhancement missions”—though he does stress that “the US conducts missions in space because it is more efficient and effective, particularly on a global basis, to do so compared to non-space alternatives.” He raises concern with the general applicability and affordability of non-space, terrestrial alternatives, however, arguing that: “the affordability of such terrestrial backups is another question. Such cross-domain alternatives only provide local solutions [and] they are very expensive to scale to provide comparable regional or global capabilities.” Berkowitz also cautions that “shifting [US] reliance to terrestrial alternatives simply trades the threats and hazards from the space domain for those in the terrestrial domains.” This leads him to conclude that, “while it is prudent to provide for multi-domain cross-strapping of essential mission capabilities,” military challenges such as anti-access and area-denial “will not make terrestrial alternatives more prudent solutions than mitigating the vulnerabilities of space assets.”

Dr. John Karpiscak III (United States Army Geospatial Center) believes that “there are all kinds of affordable non-space alternatives.” However, he offers the perspective that space actors that are already heavily invested in space and space systems, such as the US, are often too entrenched in, or committed to, their existing mechanisms to change or “adapt as readily as new technology makes their established mechanisms useless or more cumbersome to deal with.” This, he argues, increases vulnerability, and could lead to a situation in which actors that are less heavily invested in space or space systems are able to exploit weaknesses or gaps in those older systems. These actors have nothing to lose by exploiting new, rapidly evolving, and potentially competitively advantageous technologies, he contends.

Diplomatic Activities

Diplomacy is the most frequently cited affordable non-space alternative for mitigating strategic risk in the space domain. Simply put, “the United States stands to gain far more by working cooperatively with other countries to work out rules that are seen as equitable and mutually beneficial than it does from trying to gain short-term competitive advantages in space,” Gallagher argues. Weeks similarly imagines “a new vision of the US inviting everyone to the outer space development table [as] an alternative to mitigate or avoid that strategic risk.” Underscoring the affordability and ease of such a diplomatic initiative, she points out that “there are numerous mechanisms already in place that can be capitalized on.” Rossettini echoes this sentiment, firmly asserting his belief that “the best and cheapest way to prevent national security threats from or in space is” by working to develop “a clear set of rules for the use of space.” From a US point of view, he believes this diplomatic initiative would be most effective if implemented while involving “Europe as [an] ally and partner to motivate UN members to adopt” the resulting framework. Likewise, Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland) reminds us that “diplomacy is a tool that should not be forgotten,” and Armor maintains that “treaties, conventions, UN discussions, norms of behavior, ‘trust-but-verify’ monitoring, etc. all can reduce risk” in the space domain. Ultimately, the contributors generally align with the ViaSat, Inc. contributors’ simple and clear assertion: “The US and international actors have more to gain from space than from the loss of space.” As Brett Biddington (Biddington Research Pty Ltd) emphatically warns, “ultimately, all of us stand to lose if we muck up the space environment more than we already have.”

Terrestrial Alternatives

Contributors also identify several other non-space, terrestrial alternatives for mitigating or avoiding strategic risk in the space domain. However, the affordability of such alternatives, in some cases, raises questions. Hitchens contends that determining affordable non-space alternatives for mitigating or avoiding strategic risk in the space domain depends on the country in question, and its assets and terrain. She posits, however, that some space domain missions could be offloaded to air assets or fiber assets, though she warns that this would likely be a difficult initiative. Berkowitz maintains that “terrestrial alternatives exist for nearly all space force enhancement missions: launch detection and missile warning; battlespace awareness; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); command, control, and communications; positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT); and weather and environmental monitoring to mitigate the risk of denial or loss of space mission capability.”

More specifically, he suggests that pseudo-satellites could be an appropriate non-space, terrestrial alternative for PNT satellites, while airborne platforms could represent the same for launch detection, battlespace awareness, ISR, and weather and environmental monitoring satellites. However, he raises caution about the affordability of such terrestrial backups. Rossettini, like Berkowitz, identifies non- space, terrestrial alternatives for mitigating strategic risk, with the caveat that they are not necessarily financially affordable. In particular, he suggests ground infrastructure, for mitigating a lack of space asset services delivered, and defense infrastructure (i.e. antisatellite systems), for mitigating threats rapidly passing from space into the US fly zone.

Sampigethaya articulates a belief that the “US needs to explore non-space alternatives (i.e., air, land, and sea-based) to eliminate strategic risks for surveillance, reconnaissance, communications, navigation, timing synchronization, indications, and warning (SRCNTIW) capabilities.” More specifically, he suggests that alternate positioning, navigation, and timing (APNT) capabilities could help to mitigate risk relating to GPS-denied air traffic control environments. He also offers what he envisions as an interesting strategic direction: “air-based infrastructure composed of mobile platforms at different elevations—such as high- altitude balloons and autonomous unmanned aerial system vehicles—that enable a multi- layered cyber-physical system with SRCNTIW capabilities and defends against threats to and from space.”

Sampigethaya further suggests looking toward the cyber domain for non-space, terrestrial alternatives to mitigate strategic risk, contending that “recent cyberspace advances, such as data analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence, can efficiently enable effective situational awareness and decision making for [the] space domain.” Karpiscak III echoes similar thinking, suggesting that there are “things that the [US] government definitely could do better, particularly with regards to software development and the adoption of commercial standards to a greater extent.”

Conclusion

Overall, the consensus view among the expert contributors is that the United States is the international actor with the greatest strategic risk in the space domain. The United States’ dependence on space and space domain vulnerability are the primary factors cited to explain its unmatched strategic risk. Other international actors such as Russia, China, US allies, and nuclear powers in general are also highlighted by the contributors as having noteworthy levels of strategic risk in the space domain, albeit less than that of the United States.

Diplomatic activities are the most frequently cited affordable non-space alternative for mitigating strategic risk in the space domain by the contributors. Several other non-space, terrestrial alternatives for mitigating strategic risk in the space domain are also identified, but the affordability and applicability of such alternatives is not always as clear.

Contributors

Major General (USAF ret.) James Armor2 (Orbital ATK); Marc Berkowitz (Lockheed Martin); Brett Biddington (Biddington Research Pty Ltd, Australia); Faulconer Consulting Group; Dr. Nancy Gallagher (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, University of Maryland); Gilmour Space Technologies, Australia; Harris Corporation; Theresa Hitchens (Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, University of Maryland); Dr. John Karpiscak III (United States Army Geospatial Center); Group Captain (Indian Air Force ret.) Ajey Lele3 (Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, India); Dr. Luca Rossettini (D-Orbit, Italy); Dr. Krishna Sampigethaya4 (United Technologies Research Center); ViaSat, Inc.; Dr. Edythe Weeks (Webster University); Joanne Wheeler (Bird and Bird, UK)

This publication was released as part of SMA’s Contested Space Operations: Space Defense, Deterrence, and Warfighting project. For more information regarding this project, please click here.

Macro-Social Trends and National Defense Scenarios: Forecasting Crises and Forging Responses using Generation Theory in a Bio-psychosocial Framework.

Author | Editor: Shook, J. (Graduate School of Education University at Buffalo) & Giordano, J. (Departments of Neurology and Biochemistry, Georgetown University Medical Center).

Abstract

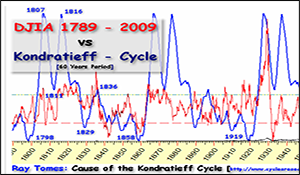

Analytic informatics and vast databases permit modeling of large populations and their economic and political behaviors over decades and centuries. Researchers such as Peter Turchin and Jack Goldstone are demonstrating how such “cliodynamics” can scientifically project large-scale trends into the future. Skepticism about social futurism is well deserved, since specific, risky, and confirmable predictions distinguishes science from pseudo-science. Employing generation theory, William Strauss and Neil Howe predicted that the next world war would occur in or by 2020. In this whitepaper, we recount how cyclical trends in social history theorized by Strauss and Howe align well with the economic and political cycles independently established by cliodynamics. Four archetypal generations (Prophet, Nomad, Hero, Artist) have followed each other in a durable pattern. Every major conflict endured by the United States has occurred when its Prophets (presently, the Boomers) reach elder leadership. Generation theory can also be applied for scenario design and strategic planning, particularly for defense purposes. Predicting actions of small numbers of people is impossible, but understanding the characteristic roles, values, and virtues of today’s generations can synergize, and add value to other bio-psychosocial-cultural analyses of group behaviors.